By Christopher Miskimon

On July 15, 1937, a convoy of trucks slowly drove up the Ettersberg, a wooded hill a few miles north of the German city of Weimar. The vehicles arrived at their destination and stopped in a line; the men aboard the trucks were ordered off. A midsummer sun beat down on the heads of the 149 prisoners overseen by guards of the dreaded SS as they lined up in rows. A photographer stole a quick moment to take a picture of the scene before the men, “enemies” of the Nazi State, were put to work.

These men unwillingly took the first steps in constructing a new concentration camp, one that would become infamous even among those places of death and misery. Soon after arriving, the camp’s newly appointed commandant, Karl Koch, selected a new name for the camp. Looking around the hill, he noted a forest of beech trees surrounding him. From then on the camp would bear the name Camp Beechwood—in German, Buchenwald.

While not an extermination camp, Buchenwald was still a pit of murder and human agony. Men would die just building the camp, and conditions only worsened over time. Slave labor, torture, medical experiments, and even suicide would all take their toll on the poor wretches unfortunate enough to pass through Buchenwald’s gates. Posted above those gates was a German proverb—Jedem das Seine—“to each what he deserves.” What a man deserved had little to do with what he would receive at Buchenwald, however. The bloody history of the camp is retold in detail in Flint Whitlock’s newest work, Buchenwald: Hell on a Hilltop (Cable Publishing, Brule, WI, 2014, 345 pp., maps, photographs, notes bibliography, index, $25.95, hardcover).

While not an extermination camp, Buchenwald was still a pit of murder and human agony. Men would die just building the camp, and conditions only worsened over time. Slave labor, torture, medical experiments, and even suicide would all take their toll on the poor wretches unfortunate enough to pass through Buchenwald’s gates. Posted above those gates was a German proverb—Jedem das Seine—“to each what he deserves.” What a man deserved had little to do with what he would receive at Buchenwald, however. The bloody history of the camp is retold in detail in Flint Whitlock’s newest work, Buchenwald: Hell on a Hilltop (Cable Publishing, Brule, WI, 2014, 345 pp., maps, photographs, notes bibliography, index, $25.95, hardcover).

The story of the camp is the story of those who ran it, an infamous list of Nazi thugs who visited unimaginable cruelty upon the inmates. Karl Koch, the first commandant, was selected precisely because he was harsh and pitiless; he was also corrupt and a thief who lined his pockets with the camp’s funds. His wife Ilsa was, if anything, even worse, having inmates beaten just for looking at her. Rumors of lampshades and wallets made of tattooed human skin surrounded the couple. The chief jailer, Martin Sommer, was a sadistic madman who tortured and killed for amusement. Heinrich Hackmann had two prisoners bend a tree and then use it like a catapult to launch another prisoner into the air. The various doctors who worked at the camp carried out numerous experiments on unwilling subjects, many of whom died.

It is also a tale of survival. The prisoners endured horrible conditions, working long hours with little food, always fearful of the capricious nature of the guards. Many persevered, survived the experience, and later were able to testify against their torturers in the numerous war crimes trials that stretched for decades after the war. Many of their personal accounts appear in this book.

While the horror of the camps is well documented, this book provides an excellent overview any serious student of World War II must have. Aside from a strict history of Buchenwald itself, the author devotes space to explaining how the camp and others like it fit into the hierarchy of the Third Reich. Attention is also given to how the Nazi system created and used the camps and how it selected and molded the men and women who operated them. There was an organized, systematic methodology used to create a large pool of people who could control and abuse the prisoners without compassion; the few who showed mercy faced demotion or transfer. The Nazi leaders knew the capacity for such bestial behavior would be hard for most to maintain, and so they systematized it. In the words of the author, the Nazi solution was to “replace the mob with a bureaucracy.”

This history of Buchenwald explains why World War II had to be fought. It is true that the common Allied soldier knew nothing of the camps while fighting. It can also be argued the Allied leadership, whatever it knew of the camps, gave little if any consideration to them while prosecuting Germany’s downfall. Nevertheless, a regime capable of perpetrating such atrocities had to be stopped. The author’s flowing prose and knack for detail make this book engaging and fascinating to read. It is the third book in a trilogy on Buchenwald; the first book, The Beasts of Buchenwald, covers the actions of Karl and Ilsa Koch and the war crimes trials that followed the war. The second book is Survivors of Buchenwald, co-written with Louis Gros, a former prisoner at the camp. Together they give a complete accounting of one of the world’s most infamous places.

For Crew and Country: The Inspirational True Story of Bravery and Sacrifice Aboard the USS Samuel B. Roberts (John Wukovits, St. Martin’s Griffin, New York, 2013, 349 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $16.99, softcover)

For Crew and Country: The Inspirational True Story of Bravery and Sacrifice Aboard the USS Samuel B. Roberts (John Wukovits, St. Martin’s Griffin, New York, 2013, 349 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $16.99, softcover)

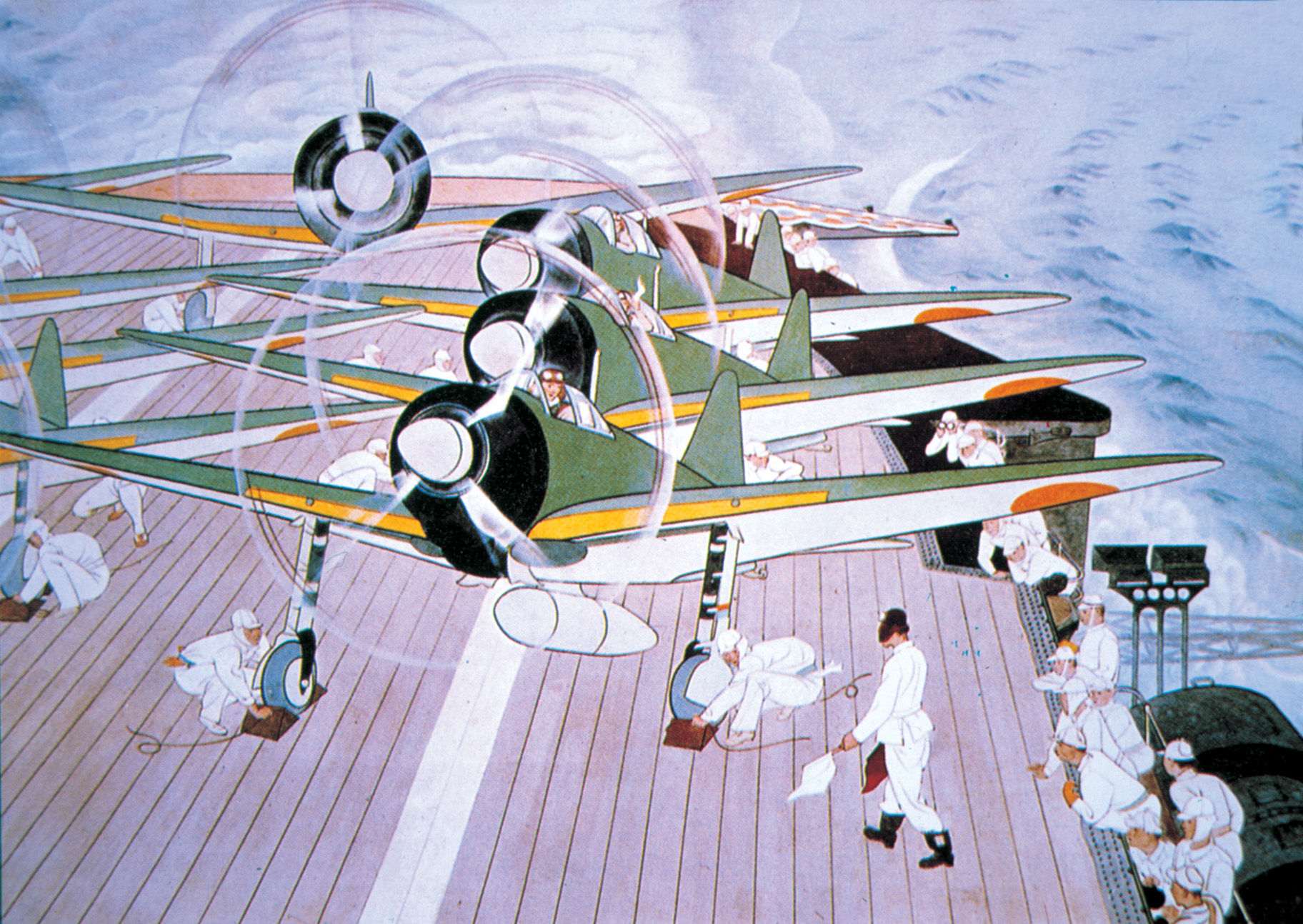

A destroyer escort was a small, light warship designed only to escort larger ships and defend them against aircraft and submarines, perhaps the odd torpedo boat. They were never designed to take on cruisers and battleships, which dwarfed them. On October 25, 1944, that is exactly what happened, however. A force of destroyers, destroyer escorts, and escort carriers designated Taffy 3 took on a major Japanese task force near the island of Samar during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. If this Japanese force got past them, the U.S. invasion fleet of transport and cargo ships would be defenseless.

Though completely outmatched, the Samuel B. Roberts and her consorts threw themselves at the enemy, making suicidal torpedo and gun runs while the carriers’ aircraft attacked with bombs meant for ground attack. The Samuel B. Roberts’ crew conducted a daring defense, and the ship was overwhelmed and sunk. The crew spent three days in the water afterward, but achieved its goal. The Japanese were driven off, and the landing force was saved. This was the only destroyer escort sunk during the war, and her sacrifice is still remembered in the annals of the U.S. Navy.

The author is a respected historian of World War II, and this book does not disappoint. Wukovits has a flair for telling the story from the sailor’s point of view, and he succeeds here. If any battle deserves the description “epic,” this one does, and any student of naval history will enjoy and learn from reading this book.

The Devil’s General: The Life of Hyazinth von Strachwitz, “The Panzer Graf” (Raymond Bagdonas, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2013, 376 pp., maps, photographs, notes, appendices, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover)

The Devil’s General: The Life of Hyazinth von Strachwitz, “The Panzer Graf” (Raymond Bagdonas, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2013, 376 pp., maps, photographs, notes, appendices, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover)

This is a biography of the German Army’s most decorated regimental commander of World War II. An aristocrat (Graf is the Germanic equivalent of an English earl), Strachwitz had fought in World War I and in the Freikorps after that conflict. The German Army encouraged leadership from the front, and Strachwitz took this to heart. He was often found at the front lines, taking his men where he wanted them to go rather than sending them.

It is perhaps surprising that he survived the war. He fought in Poland, France, and Yugoslavia before entering the maelstrom of the Eastern Front. There, he was wounded at Stalingrad but was one of the relative few to be evacuated by air. After recovery, he fought at Kharkov, Kursk, and Narva. As German fortunes waned, Strachwitz commanded various Kampfgruppen, ad hoc battle groups formed with whatever was on hand. Wounded a dozen times over the course of the war, he was lucky to be able to surrender to the Americans in May 1945 and eventually was able to rebuild his shattered life.

Tirpitz: The Life and Death of Germany’s Last Super Battleship (Niklas Zetterling and Michael Tamelander, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2013, 360 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, $18.95, softcover)

Tirpitz: The Life and Death of Germany’s Last Super Battleship (Niklas Zetterling and Michael Tamelander, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2013, 360 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, $18.95, softcover)

The battleship Tirpitz, like most German surface warships, spent most of the war denied the open sea and prospects for battle there. It was what the ship was built for, but instead small actions and Norwegian fjords were to be its fate. This did not mean the ship’s story was a dull one, however. Despite being often unable to sortie, her very existence was a threat that could not be ignored by Great Britain’s Royal Navy. Tirpitz was a menace to convoys and warships alike, and even a rumor of her sailing would divert extensive Allied resources.

To end this threat, British aircraft and midget submarines made attempts to sink the ship, efforts that eventually bore fruit on November 12, 1944. A large force of Avro Lancaster bombers dropped huge Tallboy bombs on Tirpitz, causing her to later capsize. This book by a pair of Swedish researchers is a detailed and thorough account of the ship’s history and fate. It is an enjoyable tale of a German battleship and the British efforts to destroy it.

The Fight in the Clouds: The Extraordinary Combat Experience of P-51 Mustang Pilots During World War II (James P. Busha, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2014, 256 pp., photographs, index, $30.00, hardcover)

The Fight in the Clouds: The Extraordinary Combat Experience of P-51 Mustang Pilots During World War II (James P. Busha, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2014, 256 pp., photographs, index, $30.00, hardcover)

The experiences of World War II are often best told in the words of the veterans themselves. This book collects the experiences of P-51 pilots to present an overview of that famous aircraft. The P-51 Mustang was the quintessential American fighter plane of the war, and those who flew it saw service in nearly every theater of the war from 1943 on. They escorted bombers, provided close air support to ground troops, and took on the future when they battled jets over Nazi Germany near the war’s end.

Each chapter focuses on a different period or region of the conflict. While some are predictable, such as Operation Overlord or the Mediterranean Theater, there are a few that tell lesser known stories, such as Mustangs in the Pacific and an unusual and inadvertent battle between American P-51s and Soviet Yak-9 pilots on March 18, 1945. This accidental fight had political consequences for the two Allied nations that were soon to become enemies.

Battle of the Bulge, Volume Three: The 3rd Fallschirmjaeger Division in Action, December 1944 – January 1945 (Hans Wijers, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2014, 193 pp., photographs, bibliography, $18.95, softcover)

Battle of the Bulge, Volume Three: The 3rd Fallschirmjaeger Division in Action, December 1944 – January 1945 (Hans Wijers, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2014, 193 pp., photographs, bibliography, $18.95, softcover)

The Battle of the Bulge is one of the most significant engagements of World War II and has been widely covered with literally hundreds of books on the battle. Finding new ground to cover on this battle requires delving into individual units and their specific actions, particularly those not as famously associated with the Ardennes Offensive. Stackpole Books has succeeded here with a new look at the German 3rd Parachute Division.

This unit was part of the Sixth Panzer Army fighting on the northern shoulder of the Bulge. It fought various American units, including the 1st, 30th, and 99th Divisions. The book takes the war down to the squad and individual level, providing the reader with a detailed survey of what the soldiers on the front lines experienced. Refreshingly, the author liberally uses accounts from both sides to portray what these young men went through, giving a blended look at combat in the Bulge.

Lost in the Pacific: Epic Firsthand Accounts of WWII Survival Against Impossible Odds (Edited by L. Douglas Keeney, Premiere Publishing, Campbell, CA, 2014, 193 pp., maps, photographs, glossary, index, $27.95, hardcover)

Lost in the Pacific: Epic Firsthand Accounts of WWII Survival Against Impossible Odds (Edited by L. Douglas Keeney, Premiere Publishing, Campbell, CA, 2014, 193 pp., maps, photographs, glossary, index, $27.95, hardcover)

For pilots and aircrew flying in the Pacific Theater, perhaps the worst threat they faced was the nightmare scenario of their plane going down and becoming lost in the open waters and myriad islands below. If lost at sea, they could literally drift until they died from exposure and thirst. Islands could be enemy held with the promise of capture, torture, and death; even deserted islands meant isolation and hardship.

This book contains 23 accounts of survival by aviators whose planes went down. Despite the vast efforts made to rescue downed airmen, many floated for days. Some awaited rescue even after planes spotted them because floatplanes had to be vectored in and weather often got in the way. A few reached shore and were helped by friendly coastwatchers who aided them in repatriation, often by submarine. For readers who enjoyed the recent bestseller Unbroken, this volume makes an interesting companion.

Flying with the Flak-Pak: A Pacific War Scrapbook (Kenny Kemp, Alta Films Press, Midvale, UT, 2013, 272 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, $24.95, softcover)

Flying with the Flak-Pak: A Pacific War Scrapbook (Kenny Kemp, Alta Films Press, Midvale, UT, 2013, 272 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, $24.95, softcover)

Here is another book on the air war in the Pacific giving a different perspective. When the author’s father passed away, the son took possession of his late parent’s footlocker containing memorabilia of his time as a Consolidated B-24 bomber pilot during World War II. He initially expected to use the contents for nothing more than a shadow box commemorating his father’s service. As he emptied the footlocker of its treasures, suddenly he saw something more. The result is this work revealing the day to day life of his father and thousands of other B-24 air crewmen in the Pacific.

Using a photobook-style format with lavish color illustrations, every aspect of a pilot’s life is shown, from home life before entering the service to training and deployment overseas. Once overseas they started life at a forward base, an existence interspersed with actual combat missions. All of this is shown through clear text and the imagery of relics, photographs, and artwork.

Disobeying Hitler: German Resistance after Valkyrie (Randall Hansen, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2014, 464 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Disobeying Hitler: German Resistance after Valkyrie (Randall Hansen, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2014, 464 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Valkyrie was by far the most famous of the attempts to assassinate Hitler both before and during World War II. Claus von Stauffenberg’s failed attempt to kill the Nazi dictator was the last large-scale, overt effort to overthrow the regime. Smaller efforts at resistance continued, however, right up to the end of the war. The Third Reich was suicidal in defeat; if they were to lose the war, the Nazis wanted nothing left, not a building standing or a round of ammunition unspent. It was a madness that would leave the German people destitute and starving.

Fortunately, this was a fate the more rational Germans fought in myriad small ways. Rather than active resistance they committed acts of simple but vital disobedience. When a bridge was ordered destroyed, the plunger never fell on the detonator; when a city was ordered defended to the last cartridge, white flags appeared once further resistance was futile. For those who dared disobey such orders, the cost could be their lives, but these efforts saved untold numbers of lives and preserved critical infrastructure for postwar recovery. While such disobedience has been noted often, this book brings various examples together to show the effects of the combined efforts of numerous Germans spread across many battlefields.

My Sea Lady: An Epic Memoir of the Arctic Convoys (Graeme Ogden, Bene Factum Publishing, London, UK, 185 pp., 2013, illustrations, $15.95, softcover)

My Sea Lady: An Epic Memoir of the Arctic Convoys (Graeme Ogden, Bene Factum Publishing, London, UK, 185 pp., 2013, illustrations, $15.95, softcover)

The convoys that carried weapons and material to the Soviet Union formed a vital link to that nation and faced hardship from both the weather and enemy action. Graeme Ogden was an officer aboard a trawler converted for anti-submarine duties. This ship escorted the merchantmen that plied the waters of the far North Atlantic, always watching for German submarines, aircraft, or surface raiders.

Ogden’s memoirs reveal an overlooked facet of the Battle of the Atlantic: that of an escort ship’s crew at war. Everything from an ill-trained cook to shore leave in Murmansk to an attack on an enemy submarine is given in excellent prose. Many of his day to day experiences will be familiar to sailors anywhere. The anecdotes and humorous moments combine with the terrifying times to make this book worthwhile.

New and Noteworthy

Marines Saving Lives in World War II: Semper Fi (Bud McDonnell, Kalamazoo Publishing, 2013, $15.00, softcover) This is the autobiography of a Marine pilot who served in World War II and Korea.

Marines Saving Lives in World War II: Semper Fi (Bud McDonnell, Kalamazoo Publishing, 2013, $15.00, softcover) This is the autobiography of a Marine pilot who served in World War II and Korea.

Wot a Way to Run a War! The World War II Exploits and Escapades of a Pilot in the 352nd Fighter Group (Ted Fahrenwald, Casemate Publishing, 2014, $14.99, softcover) This is a memoir of a pilot who was shot down, captured, and escaped. His combat missions are mixed with stories of daily life.

No End save Victory: How FDR Led a Nation into War (David Kaiser, Basic Books, 2014, $27.99, hardcover) The months just before America entered World War II were a critical period for the Roosevelt administration. The author shows how FDR prepared the American people for entry into the war.

Enter the Enemy: A French Family’s Life under German Occupation (Roland J. Bain, Merriam Press, 2014, $14.95, softcover) This is the story of a French officer’s family and its experience during the occupation. The daily lives of the family members are covered in detail.

Kaiten: Japan’s Secret Manned Suicide Submarine and the First American Ship It Sank in WWII (Michael Mair and Joy Waldron, Penguin Books, 2014, $27.95, hardcover) This is a history of Japan’s suicide subs and their attack on a U.S. oiler. Accounts from both sides of the engagement are included.

Kaiten: Japan’s Secret Manned Suicide Submarine and the First American Ship It Sank in WWII (Michael Mair and Joy Waldron, Penguin Books, 2014, $27.95, hardcover) This is a history of Japan’s suicide subs and their attack on a U.S. oiler. Accounts from both sides of the engagement are included.

D-Day Encyclopedia (Barrett Tillman, Regnery History, $18.99, softcover) This is a complete reference of the most important day of the war in the European Theater.

The OSS in Burma: Jungle War Against the Japanese (Troy J. Sacquety, University Press of Kansas, $22.50, softcover) The OSS conducted an extensive campaign against the Japanese in this theater. By April 1945, it was the only American unit in Burma.

Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War (John Martin Robinson, Zenith Press, 2014, $40.00, hardcover) This book profiles 20 British homes taken over for military use in World War II. Their role during the conflict is shown along with their eventual postwar fate.

World War II at Sea: The Last Battleships (Images of War) (Philip Kaplan, Pen and Sword, 2014, $24.95, softcover) This collection of rare warship photographs has been mined from archives worldwide. It shows the battleship in its final days.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments