By Robert Barr Smith

She was a tiny vessel, not really designed for the dangers and hardships of war in far places and deep waters. She was intended for short-range war in coastal waters, and accordingly, she was classed as a “Small Patrol Submarine,” as were the other boats in her class. She carried a crew of only 31, and was slow and under-armed compared to her larger sisters in the British Royal Navy and other navies of the world, and she could not dive below 200 feet, which would leave her terribly vulnerable in clear water … like that of the Mediterranean. Only 196 feet long, she could do no more than 111/2 knots on the surface and just nine submerged.

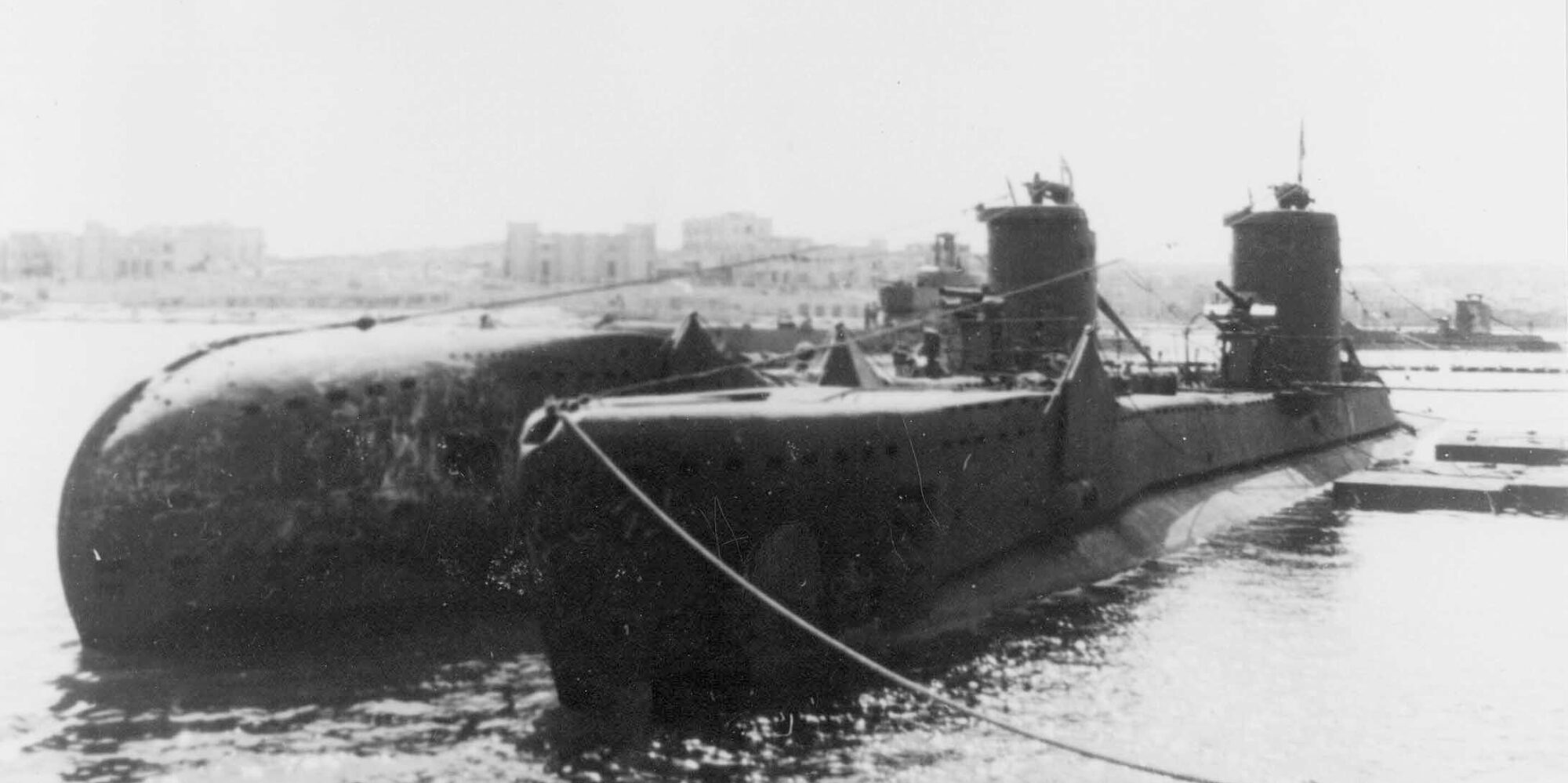

The Sub With The Funny Nose

She was the tenth of the U-class subs, and so, unlike later U-class boats, she carried not only four internal bow tubes, but a curious pair of external tubes, also at the bow. These two additional tubes resulted in a bulbous snout, which made the boat hard to manage when she fired a torpedo salvo in shallow water. The exterior tubes were phased out in later U-class boats.

She carried only eight torpedoes altogether, 21-inch Mark 8s normally loaded four at a time. They were primitive weapons by today’s standards, running straight ahead at about 45 knots without any homing capability. Aiming was accomplished by pointing the whole boat, estimating the target’s speed, calculating its angle-on-the-bow, and then firing a spread of “kippers,” standard Royal Navy slang for torpedoes. The submarine skipper got a little help from a contraption called ISWAS—later replaced by something nicknamed “the fruit machine”—which helped calculate the lead angle along which to aim. Firing from 1,000 yards, the submarine’s crew could hope to hear the “whump!” of a hit—or know they had missed—within about 40 seconds.

Hard Life Of a Submariner

Hers was a hazardous business. Life on any submarine was grueling, often downright miserable, and the undersea service was the most dangerous duty there was. While Royal Navy submarine losses did not reach the hideously high percentage suffered by the German Kriegsmarine, more than 70 British boats were lost during the course of World War II, over 40 of these in the Mediterranean.

Axis Mediterranean convoys were normally well escorted, and any British submarine could expect prolonged depth-charging. The torpedoes of the day left a clearly visible track on the surface of the water, and the convoy escorts would invariably charge down that track to counterattack. Barrages of 20, 30, or more depth-charges were common and often lethal. HMS Upholder, tiny as she was, still would prove to be a giant among warships, and her commander was equal to his tough little boat.

Indian-born Malcolm David Wanklyn was a career sailor, a product of British public schools and the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth.Tall and lean, a superb horseman and enthusiastic naturalist, he was a quiet, reserved man, generally obscured behind a large and foul briar pipe. He was, a fellow officer said, “a very strict disciplinarian … and he never set out to be popular with anybody…. But for all that, he was utterly straight with the Ship’s Company … and they all came to love him for it.” He was the sort of officer for whom sailors will dare anything at all.

Slow Progress In British Sub Development

After World War I, the Royal Navy scrapped a great many submarines, retaining two types of patrol submarines: the short-range H boats and the L-types, which were designed for longer range work. Although some of both types would see action in the early days of World War II—Wanklyn himself would command two H-class boats—they were becoming obsolescent. The H submarines, for instance, could not dive safely beyond 100 feet, an almost suicidal limitation in World War II. Nevertheless, there was little new construction until the mid-1920s.

Even then, some of the boats produced for the Navy were peculiar hybrids of no permanent value, for instance, X1, which carried four 5.2 inch guns in twin-tube turrets, and M1, which lugged around a clumsy great 12-inch gun taken out of an old battleship. Another M-boat carried an airplane. There were also the ungainly K-class boats, powered by steam. Though they would do the astonishing speed of 24 knots surfaced, they were about 340 feet long, hard to handle, and only safe down to 200 feet. The submarine service cherished the story of a K-boat skipper who telephoned his first officer in this wise: “Number One, my end is diving—what the hell is your end doing?”

Skipper Observed Atrocities During Spanish Civil War

The O, R, and P classes were bigger boats, designed as a counter to Japanese imperialism in the Far East. They were built to remain at sea for long periods over great distances. Wanklyn’s first assignment was to one of these boats, HMS Oberon, and he went on to command two obsolete H-class boats as well. In time he graduated to the new S class boats, Shark and Sealion.

In 1937 Wanklyn and Shark served in the Mediterranean at the height of the Spanish Civil War. There he learned about oppression first hand, watching German and Italian pilots striking targets in Spain. He had no use for either side in the local conflict. “Both committed atrocities,” he told his sister, “but marginally Franco’s lot were the worst.” Nothing the western democracies were willing to do could halt the agony of Spain, or halt sinkings of provision ships by German and Italian boats.

Obsolete From Birth

Upholder was laid down at the Vickers-Armstrong yards in the first autumn of the war at Barrow-in-Furness in northwest England. She was only one of 49 U-class submarines produced during World War II. While the U-class were arguably obsolete even in 1939, they were agile, tough, and easy to build. Production therefore continued. She was launched in July 1940 and completed in October, and her first—and last—captain was Lt. Cmdr. Wanklyn.

In obsolete submarine H31, Wanklyn—“Wanks” to his friends—had already spent some time on war patrol, sinking a German antisubmarine vessel off the Dutch coast. Now, he was on his way to the most dangerous submarine port in the world: Malta.

In January 1941, when Upholder arrived at her new duty station, British submarine operations out of Malta were not going well. Nine boats had been lost so far, with more than 400 crew members. Old boats mostly, they had tried to operate in a sea swarming with Italian surface vessels plus German submarines, and saturated with minefields.

Mediterranean Crucial To Britain’s War Plans

The relatively shallow Mediterranean was the most dangerous submarine theater of the war, but the survival of Malta was crucial to British operations in the Med. If Malta’s surface forces, aircraft, and submarines could consistently interdict supplies destined for Rommel’s Afrika Korps, the British could hold the littoral of the southern coast of the Med and bar the Axis’s way to Egypt. If they could not, Egypt might be lost, and with it the Suez Canal, the oilfields of the Near East … and perhaps the war. The fight for Malta would involve enormous sacrifice by the RAF, the Royal Navy, the crews of dozens of merchantmen, and, not least, the citizens of the embattled island.

The battle for the Med was, as the Duke of Wellington said of Waterloo, “a damned close-run thing.” At one point, the entire functional aviation component of Malta’s defenses was three obsolete Gladiator biplane fighters, called, with typical British optimism, Faith, Hope, and Charity. Torpedoes were in short supply; food was tightly rationed; the Navy’s ration was one slice of bread per meal, exactly what the civilian population of the island ate. Even the supply of beer, that staple of the British seaman, was scant to nonexistent. British sailors instead drank an explosive local brew called “ambeet” or, more appropriately, “stuka juice.”

Upholder Thrown Into Fray At Malta

Upholder and her little consorts would play a major role in the Allies’ rupture of the Afrika Korps’ supply lines. It would be a long, hard road, studded with tragic losses, and Upholder began it the hard way. On January 10, just four days after the boat’s arrival, the Germans began the “second siege” of Malta, hurling waves of dive-bombers against shipping in the harbor and vessels at sea. Among these was carrier HMS Illustrious, already badly hurt by six bombs at sea, and the center of an extended assault in mid-January.

As clouds of German and Italian aircraft descended on Malta, Upholder had the misfortune to be moored next to Illustrious. As every gun on Malta hurled steel at the attackers, and Upholder joined in with her Lewis guns, the carrier was deluged with bombs, sometimes almost hidden by monstrous columns of water and sheets of spray. She took one bomb, but she survived. The ship’s company of Upholder were unhurt, but they had come very close. Lying near the submarine was merchantman Essex. She was loaded with 4,000 tons of torpedoes and ammunition, and was struck by a bomb in the engine room. Her bulkheads contained the explosion, although she took 38 casualties. Had the bomb’s explosion broken through to her cargo Upholder and her crew would have been destroyed by the resulting blast.

Dry Spell And Then Success

Upholder’s early days at Malta were anything but promising. Her first patrol went reasonably well, as she torpedoed and badly damaged German freighter Duisbergand survived a heavy depth-charging by a hostile destroyer. The next three patrols, however, came up dry, to Wanklyn’s disgust. Although his crew kept their confidence in him, the commander, 10th Submarine Flotilla, began to wonder whether Wanklyn and Upholder would ever find success again.

But on April 21, 1942, Upholder found a heavily loaded Italian merchantman off Lampedusa, about halfway between Tunisia and Malta, and sent her to the bottom. Just five days later he came upon an enemy destroyer and cargo ship Arta aground off the shallows of the Kerkenah Bank, north of Tunisia’s Cape Bon. When he arrived, however, he found the water so shallow that he could not find a firing position. And so, in the best tradition of the Nelsonian navy, Lieutenant Christopher Read led a boarding party over the side of the merchantman. Read showed an unusual talent for burglary, blowing apart the ship’s lock safe and emptying it. Taking with them the contents of the safe and a small mountain of military souvenirs of the Afrika Korps, the boarders set the ship afire and departed.

Then, on May 1, Upholder got two more German merchantmen, and returned to Malta triumphant, dodging the parachute mines infesting the entrance to the harbor. There was no rest in port, however, as German and Italian aircraft struck again and again at the island fortress. There were more than 100 air raids in both February and March; in April the bomb tonnage rose more steeply still. A submarine in port dived to the bottom of the harbor when there was enough warning. When there wasn’t, casualties followed; on one day, two submarines were sunk at their moorings. At sea, two more, Undaunted and Usk, failed to return from patrol.

Big Payday In Attack On Axis Convoy

Then, in mid-May, Upholder struck gold. On station off the southeast coast of Sicily she torpedoed a 4,000 ton tanker and then, only a day and a half later, sent a big Vichy French tanker to the bottom. Operating through all of this without asdic—the British equivalent of sonar—and now down to just two torpedoes, Wanklyn went on looking for prey.

What he found was a convoy of big liners, surrounded by at least five destroyers. Without his asdic, operating entirely with his periscope, Wanklyn pushed in to almost point-blank range and fired his remaining fish. As destroyers spotted his torpedo tracks and closed in on Upholder, the torpedoes struck home. The 17,879-ton transport Conte Rosso went quickly to the bottom of the Med, taking with her almost 3,000 crew and troops.

What followed was the quintessential depth-charge attack, as the furious escorts made run after run above Upholder, dropping at least 37 charges. Wanklyn, quietly giving his orders, inspired his crew with his calm and assurance. He was, as author Sydney Hart put it in Submarine Upholder, “the perfect Englishman enveloped in an Englishman’s unemotional calm.” He remained unflustered by the creaking and groaning of the tortured hull and showers of glass from shattering lightbulbs, the heaving in and out of the boat’s sides as charges hammered her. Moving dead slow, and only when his attackers moved, thinking always one step ahead of the destroyers above him, Wanklyn brought his battered boat through.

Chalking Up More Kills On the Jolly Roger

Now Upholder could fly with pride her Jolly Roger, the black skull-and-crossbones flag on which British submarines recorded their victories. A red bar on the flag meant a hostile warship, a white one a merchantman.

In mid-July Upholder added a supply vessel to her bag, and on the same sortie torpedoed the fast Italian cruiser Garibaldi. At 4,000 yards, the little boat got two fish into Garibaldi, leaving her dead in the water with destroyers laying smoke to cover the stricken cruiser. Upholder survived a very bad barrage of almost 40 depth charges. Although Wanklyn had not sunk Garibaldi, he had taken her out of the war for a very long time.

In August, Wanklyn got a freighter and a large tanker, and could only curse his luck as he was forced to take a long and unsuccessful shot with his last two torpedoes at a flotilla of heavy warships that included a battleship. Wanklyn and his crew would have to wait until September for their greatest triumph.

Sharpshooting Submarine

A mid-September mission did not begin well when Upholder’s gyro-compass failed early on, leaving her with only her less reliable magnetic compass. But then her luck turned. Running in the dead of night, she and two consorts spotted a fast convoy, heavily escorted, headed for Libya with Axis reinforcements. Wanklyn waited until two of the three big 20,000-ton liners in the convoy were lined up overlapping, then fired a salvo of four torpedoes at long range, about 5,000 yards.

His shooting was remarkable, for he put one torpedo into liner Oceania’s propellers, stopping her, while a second steel fish blew a fatal hole in the side of Neptunia. Both ships were loaded with troops, and Upholder slipped away to reload while the Italian escorts were picking up soldiers and crew from the sinking Neptunia.

Wanklyn wasn’t through. His tubes full again, he slipped in to finish Oceania. Forced deep by an escort until he was too close to fire, he took his boat completely beneath his target, came to periscope depth on the other side, and put the liner down for good with two more torpedoes. She was gone in just eight minutes, taking with her several thousand troops who would never oppose the Allies in North Africa. Little Upholder had now sunk some 60,000 tons of Axis shipping carrying German and Italian troops to North Africa.

New Year Opens Well For Upholder

By now Upholder’s crew were exhausted, tired to the bone from the everlasting tension of combat, worn down from lack of daylight and the stale air of a boat too long submerged. The submarine crewmen wryly suggested that half the crew should breathe out while the second half breathed in. They could get almost no real rest in port, where any peace was denied them by the enemy’s bombs. They had passed the 12-months-in-combat mark, generally accepted as the limit to which a crew should be subjected. But now, in the autumn of 1941, the North African fighting continued nip and tuck, and nobody could be spared from the battle against Axis supply lines. So Upholder’s men fought on. In early November they sank the destroyer Libeccio in the Ionian Sea, not far from the busy Italian port of Taranto, and in the same attack badly damaged still another destroyer.

The year 1942 opened well for Upholder. Although she could count only a single damaged merchantman for most of its first sortie of the year, on January 2, not long before dawn, she spotted a huge submarine on the surface about 15 miles off Sicily. Wanklyn hastily dived as the Italian boat, spotting Upholder, went to high speed. Making a split-second calculation of range and angle, he fired his one remaining torpedo and hit Admiraglio St. Bon just in front of her forward gun. St. Bon, three times the size of her British opponent, disappeared without trace, and Upholder could find only three oil-covered survivors in the dark sea.

Malta Ground Zero For Bombing

However, repeated successes at sea could do nothing to relieve the profound fatigue of the submarines’ crews at Malta. Perpetual bombing, short rations, a harbor clogged with wrecks, little sleep and no real rest steadily sapped the strength of the men of Upholder and her consorts. As one British reporter described Malta under fire: “We could not see or hear anything … stones were falling shrapnel coming down like rain and planes dropping from the sky. It was terrifying, and more planes were coming in. We saw very little of this wave because of the clouds of dust which now enveloped us.”

On February 7, for example, Malta was attacked 17 times in a single 24-hour period. Captain G.W.G. Simpson, commanding the submarine flotilla, now tried for a second time to convince Wanklyn that it was time to return to Britain for a real rest, but the best he could get his determined skipper to do was take a longer-than-normal break at a country place outside the embattled port area of the island.

While Wanklyn was gone, Upholder was at sea again, commanded by Lieutenant Pat Norman. This time she got a small merchantman, but returned to find the bombs still raining down on Malta, only one of the month’s 236 air raids. Back at sea again in late February, Wanklyn got a good-sized merchantman, Tembien, and as March rolled around he was back off the Italian port of Brindisi, on the eastern heel of Italy.

Time And Luck Running Out For Little Sub

There, on March 18, he lay watching small vessels moving in and out of the boom guarding the harbor entrance. At last patience paid off: Upholder caught Italian submarine Tricheco on the surface and sent her to the bottom with two torpedoes. The next morning Wanklyn sank a trawler with gunfire, after giving its crew time to abandon ship.

Again Upholder returned to battered Malta triumphant, but her time was running out. Once back in port, she lost an officer, ordered away to his outrage and frustration, for a routine medical procedure. That officer, and a petty officer ordered to a new boat, would be the lucky ones.

Not all of Wanklyn’s missions were attacks on merchant and military shipping, although cargo and transport vessels were the critical targets in the war against Rommel’s supply lines. He also landed men of British Special Operations teams on hostile shores. These men attacked Italian shore installations, in particular the railroads, which often ran in view of the sea. On one occasion a Royal Navy sub helped out by surfacing to bombard a troop train with its deck gun.

One of these daring Special Ops operatives was a handsome young Royal Artillery captain called Tug Wilson. He and Wanklyn became close friends, and it fell to Wilson to say a last good-bye to the daring captain of Upholder, although at the time Wilson could not foresee what awaited his friend.

Last Anyone Would See Of Wanklyn And His “Little Boat”

On April 9, 1942, Upholder surfaced in the dead of night in the Gulf of Sousse, near the site of ancient Carthage. Wilson and Lance-Corporal Charles Parker successfully put two agents ashore. They made it back, finding the almost invisible bulk of the submarine lying low in the water. “Pongo approaching,” called Wilson, and Upholder’s crew quickly fished the Special Ops men and their boat out of the black Mediterranean.

The mission was Wilson’s last, as it was supposed to be the last for Upholder. And so, when Wanklyn rendezvoused with Unbeaten, bound home for major repairs in England, Wilson prepared to transfer to Unbeaten in the darkness. Because Unbeaten had serious damage, including useless torpedo tubes, Wanklyn offered his friend the option of continuing on to Malta with Upholder. Thank you, no, said the captain, “much as I love your company, David, I’ll cross over to her and take my chances.”

It was a fateful decision. And Wilson stuck to it, even as Unbeaten’s first officer called out to him in the night, “Piss off, Tug—we’ve got two feet of water in the fore-ends and the batteries are gassing.” Wilson must have looked back in the gloom at Upholder, where his friend stood on his diminutive bridge. It was the last he—or anybody else—would see of Wanklyn and his little boat.

Extreme Fatigue Of Crew And Captain Affects Judgment

Upholder had now been in almost constant action for 16 months. She had completed 24 combat patrols in that time, operating out of embattled Malta against German and Italian convoys trying to resupply Rommel in North Africa. Allied success in Africa depended on the presence of Upholder, her sister ships, and the Royal Navy’s surface warships and Malta aircraft. Montgomery’s smashing victory at El Alamein at the end of 1942 would in large part be the gift of the ships and planes of Malta and the men who fought and died in them. No vessel had contributed more to the Axis disaster in North Africa than this tiny submarine.

By now Upholder’s men were even further worn out. One of the submarine’s company had written home shortly before, telling his mother he had a bad cold, and “with that and the foetid atmosphere [I] don’t seem to have taken a decent breath for days … but,” he added, “the more blitzed we get, the more luck we seem to have against the enemy’s ships.”

Wanklyn himself was showing signs of exhaustion, and his flotilla commander was worried. He considered Wanklyn’s daring sinking of Tricheco to have been extraordinarily risky, and he worried that Wanklyn was losing the keen edge of his judgment from pure fatigue. He may have been right.

”Count the Days, They Are Not So Many”

Altogether, Upholder had sunk 129,529 tons of enemy shipping, not counting ships damaged but not sunk. In addition to her bag of freighters and troop ships, she had sent a destroyer and no less than three enemy submarines to the bottom, and damaged a second destroyer and a cruiser. She was already, in the terribly hazardous Mediterrean war, well beyond her life expectancy. In any case, this, her 25th patrol, was to be her last. On completing it, she was scheduled to return to Great Britain. Wanklyn had written his wife, back in England, to tell her it would not be long. “Count the days,” he wrote, “they are not so many. Only 59.”

But the days were too many after all, for Upholder’s astonishing luck had simply run out. This time the seemingly unsinkable little boat would not return to Malta. Nobody knows precisely what happened to her, for like so many boats of the Silent Service, she simply disappeared. The last that is certainly known is that she was part of a picket line of three boats, with Urge and Thrasher, set up to watch for an Axis convoy expected to sail from Tripoli.

Sinking Of Sub Remains An Unsolved Mystery

By extraordinary coincidence, the Italian nobleman who probably sent Upholder to her grave was the direct descendant of an English sea dog. While his given names were purest Italian, his family name was Acton. His own father had served with the Royal Navy in World War I, in one action flying his flag in HMS Dartmouth. And now Francesco Acton’s destroyer Pegaso attacked an unidentified submarine on April 14, 1942. Urge and Thrasher both heard the dull booms of depth-charging, going on and on. Subsequent attempts by Thrasher to contact Wanklyn’s boat met only silence.

On the other hand, it may well be that Upholder struck a mine on her way home to Malta, as many British officers believed. One, Captain McKenzie of Thrasher, was not convinced a destroyer had sunk his ship’s consort. He heard the depth-charging: “We thought ‘Poor old Wanks—he’s getting a hell of a bollocking.’” But he also told of picking up a later radio message to Upholder, advising her that she had been sighted by British radar close to Malta. He believed, as others did, that Wanklyn struck a mine when he was almost home. Other boats of 10th Flotilla had gone out that way, for the Med close to Malta was saturated with enemy parachute mines.

However it happened, the most famous boat in the Royal Navy was gone forever, taking all hands with her. She lies somewhere at the bottom of the Med, both tomb and monument to Wanklyn, three officers, and 27 other ranks.

Special Mention Accorded Upholder And Her Crew

Captain G.W.G. Simpson, commanding the 10th Submarine Flotilla, wrote the Admiralty to report her passing. “I hope it is not out of place,” he wrote, “to take this opportunity of paying some slight tribute to Lt Cdr David Wanklyn, VC, DSO, and his company in HMS Upholder, whose brilliant record will always shine in the records of British submarines.”

In its turn, the Admiralty publicly announced her loss with all hands: “The Board of Admiralty regrets to announce that H.M. Submarine Upholder (Lieutenant Commander M.D. Wanklyn, V.C., D.S.O., R.N.) has been lost.”

The communiqué then included a special tribute, most unusual for the stern and reticent Admiralty, for in Royal Navy tradition extraordinary courage and daring in action are expected. “It is seldom proper,” the announcement read, “for Their Lordships to draw distinction between different services rendered in the course of naval duty, but they take this opportunity of singling out those of HMS Upholder, under the command of Lt. Cdr. David Wanklyn, for special mention…. The ship and her company are gone, but the example and inspiration remain.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments