By Mike Shepherd

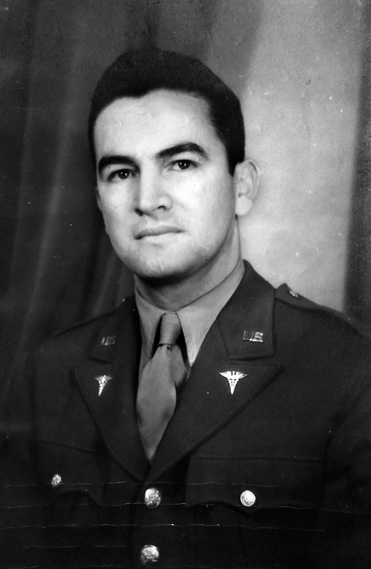

Hector Garcia was born in Llera, Tamaulipas, Mexico, on January 17, 1914, to schoolteacher parents, Jose Garcia Garcia and Faustina Perez Garcia. The Mexican Revolution drove them from their homes in 1917 and his family legally immigrated to Mercedes, Texas.

Hector’s father, a teacher in Mexico, was not allowed to teach in the United States and went into the dry goods business. Hector attended segregated schools for Mexican Americans and eventually attended college and medical school. Finding no hospital in Texas that would accept him as a resident physician, he took the advice of a staff member at the University of Houston and applied to a hospital in Omaha, Nebraska, where he served his residency.

When World War II broke out, he volunteered for combat duty. He served in the European Theater and earned the rank of major, a Bronze Star, and six battle stars. Unlike African Americans, Mexican Americans and other Americans of Hispanic origin were, for the most part, fully integrated into the United States military. As a Mexican immigrant and patriotic American, Garcia served his country well both in battle and as a medical doctor. The U.S. Army gave him the professional respect he had been denied in Texas. He was put in charge of a field hospital with about 100 staff members, mostly Anglo-American, who saluted him with a “Yes, Sir.” Major Garcia married an Italian bride, Wanda Fusillo of Naples, in 1945.

Returning from Europe to the United States, Garcia became a physician in Corpus Christi, Texas, and treated a large number of poor Mexican American patients. He also served as a local chapter president of LULAC, the League of United Latin American Citizens. As a physician, he began to help veterans with Spanish surnames to obtain services from the Veterans hospitals. Not segregated as soldiers overseas, many Mexican American troops faced segregation or discrimination when returning to the United States, including at the Nueces County War Memorial Hospital in Corpus Christi.

According to Patrick J. Carroll, author of Felix Longoria’s Wake: Bereavement, Racism and the Rise of Mexican American Activism, Dr. Garcia was able to win a middle of the night victory over racial segregation at the VA hospital in Corpus Christi in 1948.

“An acute shortage of hospital beds for veterans existed in Corpus Christi. While making rounds at Nueces County War Memorial Hospital in Corpus Christi, Dr. Hector encountered one of his Tejano veteran patients lying on a bed in the hall of the facility’s Mexican ward. Memorial segregated patients just as other institutions within the city did in 1948. Although the Mexican ward was full, there were several available spaces in the ‘white’ ward of the institution. Dr. Garcia asked the charge nurse to move his Tejano patient from the hall to a vacant bed in the Anglo ward. She said she could not do this without authorization. It was 2 am. Despite the hour, he made her call the hospital administrator at home to seek permission. The nervous and irritated nurse reluctantly did what she was told. When the sleepy Anglo administrator answered, she explained the situation to him and handed the phone to Dr. Hector. After some haggling, the Anglo consented, and ordered the nurse to honor Dr. Garcia’s request. That was the end of segregated wards at Memorial Hospital.”

As a result of this hospital work and success in changing policies as an outspoken physician in 1948, Garcia founded the GI Forum, a voice for Mexican American veterans who needed help to get medical treatment and other VA benefits. Dr. Garcia was eager to expand his organization and to persuade authorities in Texas and the United States to treat all GIs with the equal respect and honor due them as citizens who served their country.

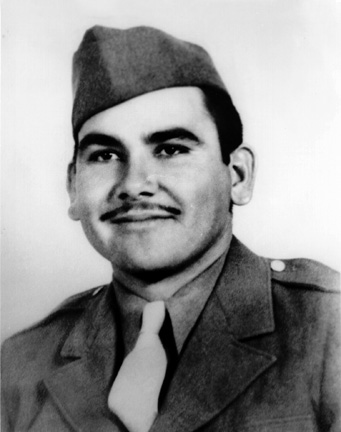

Garcia found a cause to unite his new organization when he spoke to the sister of Private Felix Longoria, a private first class who had come under fire in Luzon, Philippines, near the end of the war and died from his bullet wounds in May 1945. Longoria, a truck driver with a wife, Beatrice, and daughter, had been drafted in 1944. Seven months later, he was dead after volunteering for a scouting assignment, making good on General McArthur’s promise to return to the Philippines. Buried temporarily in the Philippines, his body was finally scheduled to arrive in his hometown of Three Rivers, Texas, in 1948. Private Longoria’s widow told Dr. Garcia that she had contacted the local Three Rivers funeral home to hold a funeral and that the proprietor, Tom Kennedy, also a veteran of World War II, severely wounded in Europe, had refused services to Longoria because of local prejudice against Mexican Americans.

Garcia immediately called Kennedy and asked again that he provide funeral services for the slain soldier. Kennedy refused again. Then, Dr. Garcia, in the name of the GI Forum, went into action. He telegraphed 17 public officials and requested assistance with a blatant case of discrimination against a veteran. Senators, congressmen, governors, newspaper columnists, all got the message. One telegram was sent to the newly elected Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas:

“Corpus Christi, Tex., Jan. 10, 1949

Hon. Lyndon Johnson

U.S. Senate

Washington, D.C.

The American GI Forum, an independent veterans organization, requests your department’s immediate investigation and correction of the un-American action of the Rice Funeral Home, Three Rivers, Texas in denying the use of its facilities for the reinternment of Felix Longoria, soldier killed in Luzon, Philippine Islands and now being returned for burial in Three Rivers based solely on his Mexican ancestry.

In direct conversation, the funeral home manager, T.W. Kennedy, stated that he would not arrange for funeral services and the use of his facilities because, he said, ‘Other white people object to the use of the funeral home by people of Mexican origin.’ In our estimation, this action is in direct contradiction of those principles for which this American soldier made the supreme sacrifice in giving his life for his country and for the same people who now deny him the last funeral rites deserving of any American hero regardless of his origins.

The Rice home is the only funeral home in Three Rivers…”

When Johnson, the future president of the United States, received the telegram, he immediately checked out the story with the editors of the Corpus Christi Caller. When the editors confirmed by telephone the story of discrimination against a decorated World War II veteran, Johnson made the decision to support the GI Forum and the Longoria family.

Senator Johnson responded to Hector Garcia by telegram the following day:

“January 11, 1949

I deeply regret to learn that the prejudice of some individuals extends even beyond this life. I have no authority over civilian funeral homes, nor does the federal government. However, I have today made arrangements to have Felix Longoria buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery…. I am happy to have a part in seeing that this Texas hero is laid to rest with the honors and dignity his service deserves.

Lyndon B. Johnson”

Senator Johnson also mentioned the possibility of burial in Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio if the family wished.

The future president had acted swiftly and decisively. When Dr. Garcia read Johnson’s telegram aloud to more than 1,000 people at a protest rally the same evening, it established the physician as an effective spokesman for his people and made the GI Forum a credible state organization that could mobilize Mexican American veterans to act. There was a public vote, and the GI Forum committed itself to supporting the burial at Arlington.

Garcia had a quick victory, but not an easy one. He and hundreds of members of the GI Forum and sympathetic family friends worked hard to raise money for the Longoria family to attend the burial in Arlington, Virginia. Many donated small amounts (one dollar or less) to a fund to fly family members of the slain soldier to Arlington. Many donations were received by mail from sympathetic Texans and others who heard the story of Private Longoria. Enough money was collected to pay air fare and other expenses so Longoria family members were able to attend.

Johnson, who as president signed several civil rights bills, was not ready for the limelight on this issue. On February 16, 1949, Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, attended the funeral at Arlington from a distance, according to Patrick Carroll.

“LBJ stuck by his decision not to allow President Truman’s office to turn the ceremony into a political photo op,” Carroll recalled. “No high-ranking officials found seating next to the Longoria family. They either stood in the wings or sat in chairs reserved for them at the rear. The senator did not except himself from this rule. When he and Mrs. Johnson arrived at the grave site, Horace Busby, his aide in charge of the cemetery arrangements, found a place about twenty yards from the ceremony where the Johnsons could view the proceedings without being photographed. LBJ and Lady Bird stood there throughout the whole event.”

Lyndon Johnson was a veteran himself with at least six months of active service in World War II as a lieutenant commander in the Navy. He was an inspector in the Pacific but returned to legislative duties on June 16, 1942, when President Roosevelt ordered members of Congress serving in the armed forces to come back to Washington.

Despite his personal sympathy for Mexican Americans (he served as a teacher and principal in Cotulla, Texas, working with impoverished elementary students of Mexican descent after college) and his long-term relationship with Dr. Garcia, Johnson was not a public civil rights proponent in 1949.

The incident, known as the Longoria Affair, received national attention, embarrassing the white citizens of Three Rivers, Texas. The national news media, including the New York Times, noted the prejudicial incident. Columnist Walter Winchell said, “The state of Texas, which looms so large on the map, looks mighty small tonight.” Dr. Garcia and his family received many insults and threats. It was an embarrassment for the Kennedy family. Some sources indicate that after all of the bad publicity Tom Kennedy approached the family and offered the use of the funeral home. But it was too late. New arrangements had been made.

Dr. Garcia’s GI Forum expanded after the incident, forming chapters in New Mexico and Colorado. As of 2009, the organization included 80 local chapters defending the rights of veterans in 13 states and the District of Columbia. Dr. Garcia and Senator Johnson continued their friendship and collaboration for many years in the pursuit of civil rights for all Americans.

Hector Garcia died on July 26, 1996, after a long career in public service. Lyndon Johnson died in Texas in January 1973, after signing more civil rights legislation than any other president in American history. Recent attempts to rename the post office in Three Rivers, Texas, after Felix Longoria were unsuccessful.

Both before and after World War II, many Mexican Americans felt themselves to be fully American. They served their country as soldiers, fought, and died for the United States of America. They began to demand equal treatment as full citizens when they returned home. The legacy of Hector Garcia lives on in the GI Forum and the broader civil rights movement.

Mike Shepherd is the son of a Marine and a lifelong Texan. He has served as a bilingual teacher in Dallas for 31 years. He lives in Duncanville, Texas, with his wife Dana and his son, Caleb.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments