By Peter Suciu

While Austria’s Hapsburg Dynasty fell at the end of World War I, its legacy can still be seen throughout Vienna in its numerous palaces and museums. It is the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum that is most closely associated with the military history of the Austrian people. Located in the Landstrasse district of the Austrian capital, it is fittingly not all that far from the Belvedere complex, which served as the summer residence for Prince Eugene of Savoy—the French-born general who first saw action for his adopted home during the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683. It is also fitting that the building’s history is tied closely to another infamous event in Austrian history, the revolution of 1848.

While the Austrian Empire was able to hold itself together thanks to aid from its Russian ally, following the war it was decided that the capital needed a new military barracks. The result was a complex that was dubbed the “Arsenal.” Its location was actually just outside the palace district, and for good reason.

“It was within artillery range, but still provided enough room for the troops to drill and be ready in case there was another revolution,” Christoph Hatschek, vice director of the Heeresgeschichtliches, told Military Heritage: “This provided an ideal location for the troops to be barracked.”

Moreover, it also allowed for what was to be the first museum to be built in Vienna. While the Arsenal was to house the soldiers, it also was meant to contribute to the royal capital of the city with handsome buildings that were in keeping with the beauty of Vienna. The original intent was that the Arsenal would house the arms and armor collection of the Hapsburgs, and the original contract called for a building dubbed the “Waffenmuseum” (Arms Museum).

“While the original plan was to house the collection of medieval armor at this complex, in the end there was not enough space,” said Hatschek.

However, the final building, at 235 meters in length, was large enough for the military collections of Austria up to that point. Designed by architect Theophil Hansen, the Heeresgeschichtliches is one of the oldest and largest purpose-built military museums in the world. Construction on the building began in 1856 at the behest of Emperor Franz Joseph I, with the museum’s original purpose to chronicle the history of Austria.

When the building was completed in 1872 it soon became apparent that no actual consideration was given to displays or artifacts to exhibit. Finally, in 1891 the museum was opened as the Heersmuseum (Army Museum), and Emperor Franz Joseph I made his first visit. It was to be short lived, though, and less than 25 years later the museum was closed due to the outbreak of World War I.

The museum reopened in 1921. The collection was greatly expanded with artifacts from World War I, and for the first time included a significant number of paintings.

In 1938 Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in the Anschluss. The Heersmuseum then fell under the control of the chief of army museums in Berlin. The museum remained open during the early stages of World War II and was used to stage special exhibitions that glorified the German victories in France and the Low Countries. As the tide of the war turned against the Germans, the collection was relocated to cache depots throughout Austria. The building was severely damaged during a U.S. air raid on September 10, 1944. The north-east wing was destroyed as were many of the artifacts in the depots.

“The building was not the only part of the museum to suffer during World War II,” said Hatschek. “Following the war it was necessary to rebuild the collection.”

The rebuilding of the collection and the buildings began in 1946. It was decided not to merely refill the building, but rather to design a historical museum with a more integrated character that chronicled Austria and its peoples. The museum consists of four large exhibition halls spread out over two floors along with a gallery of armored vehicles outside the museum. The collection at the Heeresgeschichtliches begins with the Thirty Years’ War and the conflicts with the Ottoman Turks. Beginning on the upper level, the museum now chronicles the Thirty Years’ War to the time of Prince Eugene of Savoy and does include some infantry armor of the post-medieval era. The gallery contains figures of various 17th-century Austria soldiers including an imperial pikeman and imperial musketeer, as well as numerous small arms used in the era. Paintings in this gallery present the romanticized view of the wars of the era and include portraits of early Austrian rulers, such as Frederick V, Elector Palatinate.

This gallery is also notable for the numerous objects that are not Austrian but rather Turkish and were captured following the unsuccessful Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683. The collection includes numerous compound bows, quivers, and even stirrups. Yet it is the Turkish colors that is the prized artifact from the siege. Captured outside the city, the banner features the Islamic creed: “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet.”

This first gallery also contains paintings of the siege, as well as a large painting of Prince Eugene of Savoy by Johann Gottfried Auerbach and numerous items of clothing belonging to the French-born general, who became one of Austria’s most successful military leaders. The prince’s funeral pall is also on display at the museum.

Just as Austria’s wars with the Turks ended, the War of the Spanish Succession began. During this period the Hapsburg monarchy became a major power in central and southeastern Europe. This was followed by the War of the Austrian Succession, which saw Maria Theresa emerge as one of Austria’s most important rulers, and fittingly the museum chronicles her rise to power and her four-decade reign (1740-1780). This is when the Austrian Army took on a more national characteristic, and military training improved as the empress established a military academy.

Artifacts in this collection include Austrian infantry colors and numerous spoils from the Seven Years Wars, including Prussian broad-swords and bayonets. Most impressive is the captured “Color of the Royal Prussian 17th Field Regiment” from the army of Prussia’s King Frederick the Great. This is especially valuable to the museum as stocks of the armory in Berlin, which contained many other relics and artifacts from the Kingdom of Prussia, were destroyed during World War II.

The Hall of Revolution contains the portraits of Emperors Joseph II and Leopold II, as well as Baron Ernst Gideon of Loudon, along with numerous artifacts that show the changing technology of the battlefield at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. There are several highly exquisite examples of late 18th-century Turkish muskets, which are richly ornamented and probably had belonged to high Ottoman dignitaries. These were likely taken as spoils of war by the emperor-to-be Francis II, who was the last Holy Roman Emperor, later the Austrian Emperor Francis I.

The hall contains a French observation balloon, believed to be Intrepide—one of six such special observation balloons used by the French Army in special airship companies between 1794 and 1799. The particular example in the Heeresgeschichtliches was captured by Austrian troops in the Battle of Würzburg on September 3, 1796.

Several excellent examples of late 18th- and early 19th-century uniforms are also on display, including that of a hussar of the Imperial Hussar Regiment and Landwehr infantryman. The gallery also contains an anonymous portrait of the Austrian State Chancellor Prince Clemens Lothar Metternich, who played a leading role in the reorganization of Europe following the Napoleonic Wars.

This wing of the museum then continues from the time of the 1848 revolution, which nearly saw the end of the Austrian Empire, to the foundation of the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy in 1867. The gallery features many paintings of Emperor Franz Josef I as a young man. It was following the 1848 revolution that Emperor Ferdinand I abdicated in favor of his nephew, Franz Josef.

There are also numerous artifacts that belonged to Field Marshal Count Joseph Radetzky, the once powerful supreme commander of the Austrian Army, who achieved victory against the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont.

The hall chronicles the Austrian and Prussian victory against Denmark in 1864 as well as the defeat of Austria by the Prussians in 1866. Among the unique pieces on exhibit are the Austrian muzzle-loading Lorenz rifle and the Prussian breech-loading Dreyse needle gun.

Somewhat surprisingly, the museum houses a small collection devoted to Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, the former Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, brother of Emperor Franz Josef I. Maximilian assumed the Mexican crown after French Emperor Napoleon III assured him of his assistance. But Napoleon III reneged on that promise, and after the American Civil War Emperor Maximilian found himself very much on his own. He was captured by Mexican forces and executed in June 1867. The Heeresgeschichtliches contains not only the emperor’s death mask, but also a standard of the Imperial Mexican Hussar Regiment and several helmets, shakos, and rapiers used by members of the Mexican Life Guard.

After the suicide of Crown Prince Rudolph, it was hoped that Archduke Franz Ferdinand would be the reformer and could keep Austria out of a future European war. Instead, his assassination in 1914 ignited the war that was to end the Hapsburg dynasty.

The Franz Josef gallery includes many of the emperor’s possessions along with a vast collection of uniforms and artifacts of the Austro-Hungarian Army from 1866 to 1914. Next is the gallery of World War I, which has been reorganized for the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the conflict. Among the most notable pieces is the so-called Sarajevo car, a Graef and Stiff that was built in 1910 and was used by Archduke Franz Ferdinand on the day of his assassination. The car has numerous bullet holes.

The World War I collection includes many uniforms and pieces of equipment that suggest that while Austria fought a war that largely avoided the trenches that are so iconic of the Western Front, it was not spared the horrors of the conflict. The collection also reinforces that Austria fielded an ethnically diverse army.

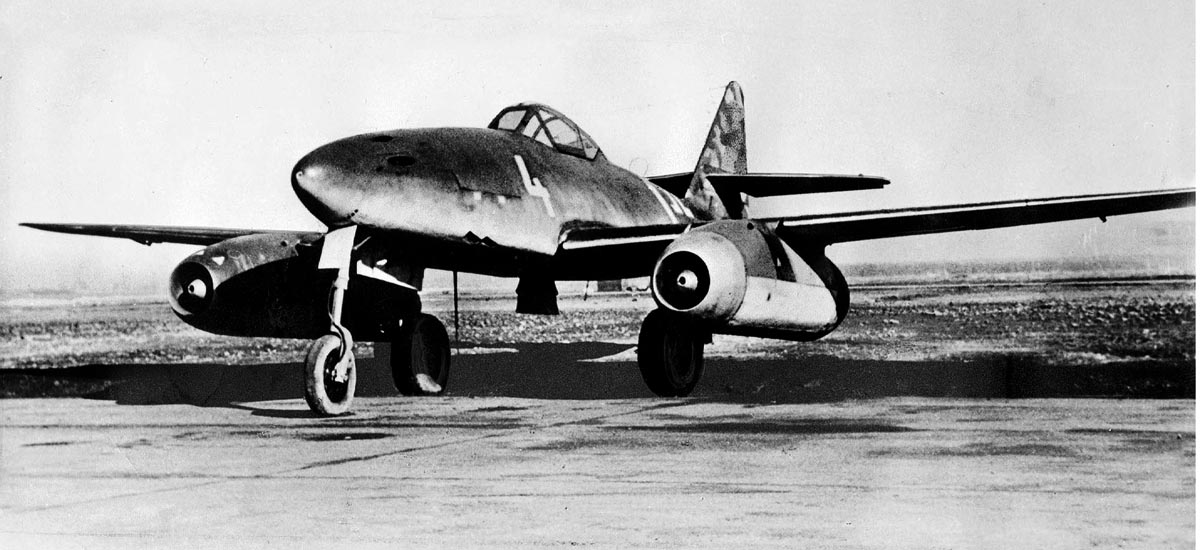

The museum then chronicles World War II, but not specifically to Austria so much as just exhibiting artifacts from the war.

“We cannot escape the fact that Austria was at the time part of the German Reich,” said Hatschek. “However, there was no specific Austrian unit—far from it, as Austrians were meant to be integrated into the German Army. So while it is true Austria could be seen as the first free nation to fall to the Nazis, Austrians had a role in the war as well.”

The collection includes an exhibit of war remnants from the battlefield around Stalingrad, and while there was no specific Austrian unit within the German Army, the museum does contain a fanion of the First Austrian Volunteer Battalion. This unit was raised from Austrian prisoners in 1944 by the Allies, but was only deployed for occupational purposes.

Other artifacts include a full German 88mm Flak 36 antiaircraft gun that was used against Allied bombers during the air raids against the city. This is contrasted by an exhibit featuring the figure of an American bomber pilot.

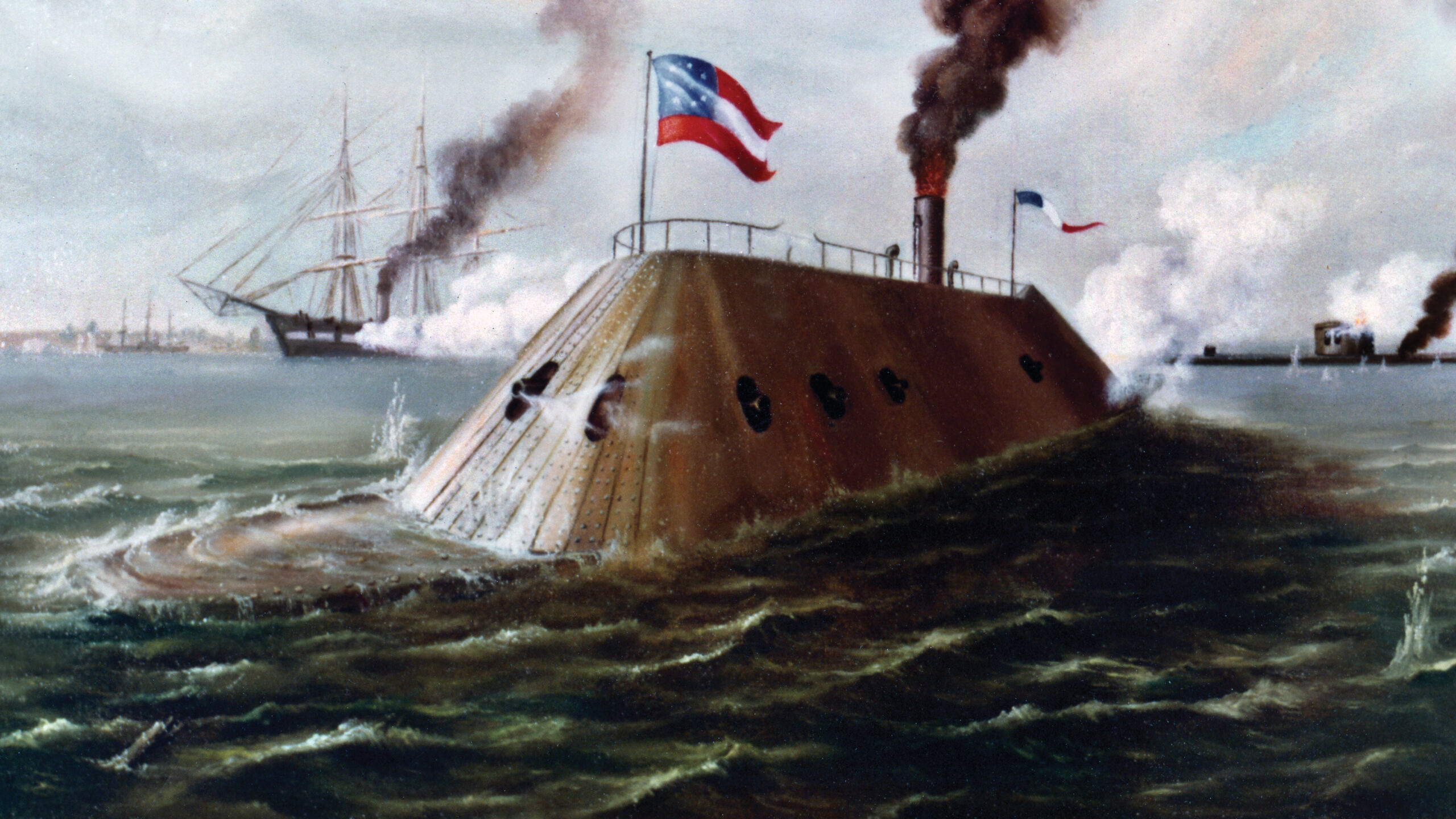

At the end of the ground floor of the Heeresgeschichtliches is a notable gallery of Austrian naval history, which is all the more unique today given that the nation is now landlocked. For much of the 19th century the empire had access to the sea in lands that today include Bosnia and Croatia. It is also notable that the museum’s gallery chronicles the naval race against Austria’s then-ally Italy. This serves to educate visitors that even though Austria did not have overseas colonies, it did play a role that is largely forgotten in the Boxer Rebellion in 1900.

Another facet of the museum’s collection is on permanent display outdoors. This includes one of the world’s largest collections of bronze cannons, many of which are displayed on the grounds outside the main museum building. It also includes foreign artillery from Venice and the Ottoman Empire as well as several French examples.

The Austrians created the first armored-car type vehicle for the military that utilized not wheels but tracks. This was actually designed by Colonel Gunther Burstyn in 1911, five years before the British introduced tanks on the Western Front during World War I. While one is not on display, the museum does offer a “tank garden” of vehicles used by the Austrian armed forces after 1955.

In all it is an impressive museum, summed by the manager of the well-stocked gift shop, who said, “It is a good museum; it is far from the worst.” Modest words, indeed.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments