By Duane Schultz

Lieutenant Martin Andrews was not scheduled to fly that day. He and his Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber crew had survived 12 missions out of the required 25 and were due for a much needed week of rest and recuperation. But that was cancelled at the last minute, and Andrews and his crew faced their longest mission yet, to Stuttgart in southern Germany. It was Monday, September 6, 1943.

By the time Andrews and his crew left the target at Stuttgart, their instrument panel was shattered, one engine was out, another was trailing smoke, and the fuselage was riddled with holes. Andrews knew there was no way they could make it back to England. Their only hope was to try to reach the safe haven of neutral Switzerland. He realized they would be interned there, but at least they would be alive, not rotting away in some Nazi POW camp.

Andrews managed to land the damaged plane on a grassy field. Immediately the Americans were surrounded by Swiss troops armed with rifles. They took the American airmen to a barracks where a Swiss intelligence officer was waiting. “What are you doing in my country?” he asked. Andrews looked at him and smiled. “We’re tourists.”

Andrews and his bomber crew were one of five crews that landed safely in Switzerland that day. Of the 388 bombers that had set out from England that morning, 40 others did not return; their crews were either captured or killed. In total, 137 Allied four-engine bombers and nine fighter planes landed in Switzerland during World War II, and 1,704 airmen were interned, including some who bailed out over occupied France and were able to reach the Swiss border.

But not all the American aircrews that crossed the Swiss border survived. As many as 15 planes were shot down over Switzerland by Swiss pilots flying German-made Focke Wulf FW-190 fighters or by Swiss antiaircraft fire. Some 36 airmen were killed.

It is not known if these casualties were cases of mistaken identity or deliberate acts of revenge for the destruction and death that U.S. fliers had inadvertently caused in Switzerland. For example, on April 1, 1944, as a result of malfunctioning radar, intense cloud cover, and human navigational error, 38 Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers dropped 1,200 bombs on the Swiss city of Schaffhausen, 120 miles south of the intended target in Germany. Much of Schaffhausen’s downtown district was destroyed; 40 civilians were killed and 270 injured.

In February 1945, there were 13 accidental American attacks on small Swiss towns that caused 21 casualties. A month later, American planes dropped 12 tons of bombs on Basel and 20 tons on Zurich, leaving six dead and 50 wounded. Animosity grew on both sides. The American high command became convinced that the Swiss government was full of Nazi sympathizers. The president of Switzerland, Marcel Pilet-Golaz, publicly declared the American bombings to be errors but privately espoused the opposite view—that the attacks were “a deliberate retaliation for Switzerland’s ties to Germany.”

Despite the efforts of both parties to calm the situation, there were more incidents. Some were clearly unintended, but there were also times when Swiss fighter planes attacked American bombers that were trying to land in Swiss territory. Less than two weeks after the Schaffhausen bombing, fighter planes of the Swiss Air Force attacked an American B-17 even though the pilot had lowered his landing gear and fired off flares, internationally recognized signs of distress. Six of the American crew of 10 were killed.

Nevertheless, the Swiss government treated Americans who landed on their soil according to the terms of the 1907 Hague Convention, which dictated that all foreign troops had to be interned until the war was over. However, German airmen downed in Switzerland were quickly repatriated to Germany. Sweden, also a neutral country, repatriated the crews of the 140 American planes that landed there.

Like Martin Andrews’ plane, almost all American bombers landing in Swiss fields were met by soldiers with rifles at the ready. On July 21, 1944, a badly damaged B-24 named Ginny Gal made a forced landing at a Swiss air base. The navigator, Lieutenant Strickland Holeton, reported that he saw eight or nine other Liberators that had landed ahead of them.

When he and his crew jumped out of the plane, they faced a line of armed soldiers. Holeton’s first reaction was to get back in the plane, but one of the Swiss soldiers handed him a cigarette. “Is OK, is OK,” he said. “Ich bin Swiss. You get flight pay!” referring with envy to how well the Americans fliers were paid. Holeton thought it was a promising beginning to their internment.

Jack McKinney, a B-17 co-pilot, recalled the “soldiers waiting for us to get out of the airplane. ‘That’s it’ I thought. ‘They’re Germans. They sure look like it.’ But then a little boy about 10 or 11 runs up and says ‘Die Schweiz. Ist gut.’ I gave the little fellow my helmet and goggles.”

All the Americans went through the same procedures. They were interrogated by Swiss intelligence officers and asked for details of their last mission. Some airmen answered without hesitation, while others, like Andrews, refused to reveal anything beyond name, rank, and serial number. But whether or not they cooperated, they were not threatened, though Andrews said that he was warned by his interrogator, “I would advise you not to try to escape, lieutenant. Our soldiers are very good shots.”

They were taken to temporary quarters in isolated mountain villages for periods ranging from three weeks to several months. Accounts of their confinement report that the men were allowed to attend church services, take long walks on the mountain trails, and to eat as many wild strawberries as they liked.

Andrews and his crew were sent first to a remote spot high in the Jura Mountains, where, as historian Robert Mrazek wrote, “Morale fell quickly. Some of the pilots shared Andy’s sense of guilt at having flown out of the war…. Others began to realize they might have to languish in an internee camp for years.” Decades after the war Andrews wrote, “My only solace is that I preserved the lives of the members of my crew.”

In November 1943, Andrews’ crew and others were sent by bus to a camp at Adelboden, which lifted everyone’s morale the moment they saw it. A Bernese alpine resort, Adelboden accommodated the Americans in the seven-story Nevada Palace Hotel. The men had access to the skating rink, ski slopes, restaurants, and bars, and even a piano recital hall. The rooms had balconies offering magnificent views. The Americans were also free to walk back and forth to the neighboring villages.

There had not been any tourists in the Adelboden area since the beginning of the war, so the locals made a great effort to make the Americans (with their flight pay, which continued through their internment) feel welcome. However, the basic resources the Swiss could provide under wartime conditions were limited. Food and coal were tightly restricted because the borders were closed to imports, and food rationing was enforced throughout the country.

Pilot Charles Cassidy recalled years later, “The food was pretty basic: brown bread, home-grown vegetables, Swiss cheese, butter, but not too much meat, and ersatz coffee.” But, he added, “The beer was good.”

According to American historian Cathryn Prince, “The Nevada Palace, like other hotels across the country, was kept unheated. In the winter months, the water in the washbowls and toilets froze. The airmen often ate breakfast with gloved hands.” It was not quite the paradise it had appeared to be.

The local residents, many of whom spoke English, were very friendly. The Americans found many of the young women to be attractive and available. “The boys always wanted to go walking and hold your hand,” one 18-year-old said. Two Americans married Swiss women during their stay, and two more marriages took place after the war.

Private Norris King, a waist gunner on a B-17, wrote, “I remember at Christmas time [1944] the local children were invited to our hotel to see the movie, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. And I also remember loading a sled with gifts and taking it to a less fortunate family. I feel we were well accepted by the people of Adelboden.”

“The Americans were entertaining,” said a 12-year-old Swiss boy. “They always had money and lots of chewing gum. Most important for us, they had Jell-o!” Another Swiss, who was a child during the war, recalled that the Americans “were like angels from the sky.”

As the number of internees mounted, the Swiss had to find more sites to accommodate them all. One was set up at Wengen, two hours away from Adelboden, and a larger one at the renowned resort of Davos. It was also decided to separate officers and enlisted men into separate camps, and the officers were assigned to Davos.

The main hotel in Davos, where most of the Americans were housed, was the Palace, where the desk clerk took pride in showing off two signatures in the hotel ledger from famous writers of the previous century, Robert Louis Stevenson and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Another distinguishing feature of the Palace is that it was across the street from the German consulate. Over the building’s front door, facing the Americans every time they stepped out of the hotel, was a three-foot-tall eagle atop a swastika, the formal symbol of the Nazi party. The idea of being that close to the enemy was too hard for some internees to resist; on July 4, 1944, they managed to launch a bunch of firecrackers and homemade rockets at the building, then stole the Nazi emblems.

Both the Germans and the Swiss were outraged. It was illegal in Switzerland to insult foreign flags or emblems. Swiss soldiers surrounded the Palace Hotel, and the senior Swiss officer ordered all the Americans to gather in the dining room. He announced that they would be confined indoors and deprived of food until the German emblems were returned. They were given back, and the two American officers who had taken them, Lieutenants Oscar Sampson and John Garcia, were arrested and sent to a punitive camp. They escaped the following day and made their way back to England.

The Americans tried to keep busy playing cards and sports, having snowball fights, and learning how to ski, an adventure that resulted in several broken legs. They established classes taught by fellow internees. In the warmer months there was swimming and sunbathing. The bare skin they so casually displayed shocked some of the locals—and tantalized others.

Other than adhering to a nighttime curfew, there were no restrictions. “We had our freedom,” Charles Cassidy said, “as long as we were present for bed check. Several times, to break the monotony, we hiked through the valley and over the pass to Klosters, about three kilometers from the Austrian border, to eat at a small café.” They were even permitted to take tours of the countryside lasting several days.

Some admitted that though they were bored with their situation they were grateful to be safely out of the war. Others felt demoralized, guilty, and embarrassed that they were safe while their buddies were still flying dangerous missions over Germany, wounded or killed every day while they swam in the hotel pool or danced in the hotel ballroom.

They were determined to escape, despite warnings from their captors that if caught they would be sent to a prison camp rumored to be as harsh as the ones in Germany. The rumors were true, but many wanted to get out anyway, regardless of the consequences. A few men were able to leave without having to attempt to escape. In February 1944, Martin Andrews and six others were chosen by Allen Dulles, then head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Switzerland, to be repatriated in exchange for seven German airmen also being held in Switzerland.

Dulles had collected so much vital intelligence on the German war effort that he dared not risk sending it back to the United States by radio. His idea was to have the seven American airmen memorize the information and deliver it to Washington. Two weeks later they crossed the border into Germany and boarded a passenger train filled with German troops. Their route took them through Germany and occupied France to the border of Spain. And from there they flew to Washington.

When the captured American airmen first arrived in Switzerland they had been warned that anyone caught trying to escape would be considered a criminal under international law. And even if they succeeded in escaping from their Swiss internment site and reached American lines they would be court-martialed, returned to Switzerland, and jailed.

But that was not true, even though they had been given that warning by Brig. Gen. Barnwell Legge, the American military attaché in Bern, the Swiss capital. Lieutenant James Mahaffey recalled General Legge’s “Welcome to Switzerland” speech to the new internees: “I’ll never forget that pompous SOB Legge. Strutting around, dressed in his cavalry boots, swagger stick under his arm, telling us how lucky we were, how nice Switzerland was and ordering us to make no attempts to escape. Of course, this was contrary to our own Air Force orders to ‘make every effort to return to your unit.’”

Despite the threats from General Legge and the rumors of rough treatment awaiting escapees, just over half the internees tried to get out. Of the 948 who attempted to escape, 184 were caught, leaving 764 who made it to freedom. In many cases, they were actively helped by Swiss citizens. Many other Swiss made no effort to inform the authorities if they came across fleeing Americans.

Those caught were labeled “prisoners” rather than “internees” and were sent off to a penitentiary camp called Wauwilermoos, built in a swamp outside the city of Lucerne. It was one of three maximum security prisons in Switzerland for violent criminals; the inmates included Russians, Poles, Italians, French, Yugoslavs, British, and Germans. By the last months of the war, the camp also housed 376 Americans, escapees as well as those convicted of being drunk and disorderly or of violent behavior.

The men lived behind double rows of barbed wire with watchtowers and vicious guards armed with submachine guns and patrolling with dogs, which were sometimes set upon the men simply for the guards’ amusement. The flimsy wooden barracks were not heated and had been built to house 20 men each, but as many as 90 were forced to live in each one. Beds were wooden planks or just a pile of straw on the floor. The latrines were open trenches lined with bricks, cleaned once a week by the inmates.

Sergeant Daniel Culler, a tail gunner on a B-24, wrote, “As I entered the barrack, the stench was mindboggling. One look at the inside and I knew this was a place designed to break prisoners down to nothing more than the lowest type of earthly creature. The Swiss treat their animals better than this.”

The men were given little medical care and barely sufficient food. “Our daily meals were cabbage soup,” Lieutenant Larry Lawler said. “We got our protein from worms that were in the cabbage.” The men lost as much as 40 pounds during their time in Wauwilermoos.

A 20-year-old American was repeatedly beaten and sexually assaulted by a gang of Russian prisoners, and the camp commandant refused to respond to his pleas for help. “Even death … would have been more welcome than what I was about to face,” the American later wrote.

As a result of the inadequate diet and poor sanitary conditions, the men became sick with dysentery, boils, and a variety of diseases that would not have been difficult to treat had decent medical care been made available.

The camp commandant was a sadistic, 47-year-old Swiss Nazi, Captain Andre-Henri Beguin. Lieutenant James Misuraca commented that Beguin was “a hater of Americans, a martinet who seemed quite pleased with our predicament.” Beguin also frequently refused to distribute Red Cross parcels and mail to the Americans.

After the war, Beguin was court-martialed by the Swiss Army for fraud, adultery, and extorting money from his staff. He was given a 3 ½-year prison sentence. However, no one, including Swiss authorities, the American legation, or the International Red Cross, protested against his brutal treatment of prisoners during the war. A report by the International Red Cross declared, “There isn’t any abuse here, but on the contrary strict control on the part of the commandant of the Camp.”

All that was about to end as American troops who invaded the south of France neared the Swiss border. General Legge made preparations for the repatriation of the American internees. The first repatriation occurred February 17, 1945, when 473 Americans left Adelboden for their long journey home. The airmen may have been relieved, but not so the Swiss. “The day they left, the whole village cried,” Margrit Thuller said. “Our friends were leaving us.” Other groups departed over the next three months until, finally, on May 29, 1945, just 19 days after the German surrender, the last American airman detained in Switzerland was taken across the border. The war was finally over for the men whose planes had landed in Switzerland.

When they returned to the United States, however, they found a different kind of war, a battle to reclaim their honor and reputation, to win formal recognition as prisoners of war. Many of their fellow airmen, and many civilians as well, believed that those who landed their airplanes in a neutral country did so for only one reason—to sit out the war.

Colonel Archie Olds, an Eighth Air Force wing commander, remembered how angry he grew every time he saw planes heading toward Switzerland during a mission. “I sat in my cockpit and cussed those sons of bitches when I would see them leaving. I didn’t really know whether they were crippled or not.” Others thought that internees were slackers, just cowards living an easy life. Rumors spread on the American bases in England that some internees had even packed their bags with civilian clothes and liquor to take on their next mission so they could make the most of their so-called holiday in Switzerland.

Lieutenant Leroy Newby recalled decades later, “It was an inside joke among all of us that if we ever got anywhere near Switzerland, we would feather an engine and wing it for the Promised Land. We had heard tales of downed fliers living in swank resort hotels, drinking fine wines, eating good food, and dating bad girls.”

Those in high command grew concerned about the effects of the rumors on the morale of those flying combat missions. On July 29, 1944, General Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz, commander of all the Air Forces in the European Theater, wrote, “We resent the implication that these men are cowards, are low in morale, or lack the will to fight. Such is a base slander against the most courageous group of fighting men in the war.”

Two weeks later Allen Dulles wrote, “No case of any nature has come to the attention of myself or [General Legge] giving the least credence to the report that American airmen are attempting to evade any more combat by landing here. I believe this nothing but ill-willed propaganda inspired by Nazis.”

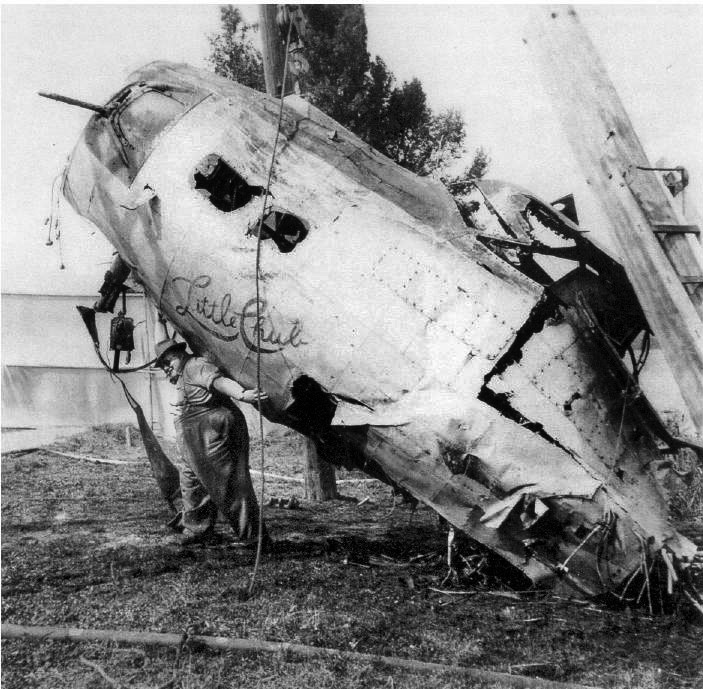

Not long after the German surrender, General Spaatz sent several hundred technicians to inspect the planes that had come down in Switzerland. Their reports indicated that all but one or two were sufficiently damaged, disabled, or low enough on fuel to have been unable to return to England. But even that report did not dampen the rumors about those who had been interned in Switzerland. No mention was made of the men who tried to escape their confinement, and it was not until 1996 that the U.S. government officially recognized that Wauwilermoos had been a brutal prison camp.

Even then, Americans imprisoned at Wauwilermoos were not granted formal POW status, which meant that they could not receive medical and financial benefits or disability compensation for injuries or illnesses due those who had been certified as prisoners of war. It was not until nearly 70 years after World War II ended in Europe, on April 30, 2014, in a ceremony at the Pentagon, that the U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, General Mark Welsh III, presented Prisoner of War Medals to eight survivors of Wauwilermoos (a ninth medal was presented to the son of a Wauwilermoos survivor).

These men were finally granted their POW status thanks to the 15-year effort of a history professor at West Point, Major Dwight Mears, whose grandfather (Lieutenant George Mears) had been a prisoner at Wauwilermoos.

One of the men honored that day, Alva Moss, who had bailed out of his flaming B-24 over Switzerland with both legs full of shrapnel, talked to a reporter after the ceremony. “This is a great time for us,” he said. “Everyone was together again.” Then he added—as though it was something he had been waiting for many years to say—“and there were no slackers.”

Duane Schultz has written more than two dozen books and articles on military history. His most recent book is Patton’s Last Gamble: The Hammelburg Raid (Stackpole, March 2018). He can be reached at www. duaneschultz.com.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments