By Blaine Taylor

One query that was raised on the Allied side in 1942—two years before Operation Overlord—was if the cross-English Channel invasion of Northwest Europe via France was necessary at all in order to defeat the Third Reich.

Could Nazi Germany have been beaten by Allied air power alone, without the shedding of blood in costly ground-combat battle? Today—almost eight decades later—that cogent question persists.

One who thought so at the time was Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, chief of the British Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command. On September 3, 1942, Harris sent a top-secret memo to Winston Churchill: “Prime Minister: It is urgently necessary that a decision should be arrived at as to the future main strategy of the war…

“Both the future possibilities and the past results point to the inevitable conclusion that no matter what other operations are engaged upon, the final decision—if it is to be in our favor—must come through a direct air war between the United Nations and Germany.”

He concluded, “Germany could be so devastated and dispirited by bombing,” making an invasion “a mopping-up operation,” and proposed the total destruction of “30 or 40” major German cities and industrial sites.

Was this a gross oversimplification of Allied air might? Let’s take a closer look. Dudley Saward in Bomber Harris wrote, “The German Air Force was almost non-existent as a weapon of defense or offense from April 1944 until the end of the war…. The indications are that Germany would have collapsed under bombing alone, which was what Harris always believed to be a certainty….”

Is it possible that the Combined Chiefs of Staff feared that a sudden collapse of Germany—brought about by bombing—would have resulted in the Russians sweeping across Germany with no opposition, and even occupying parts of France, Belgium, and Holland, before the British and American occupying forces could gain any worthwhile foothold on the Continent of Europe?

The man responsible for Germany’s war production from early 1942 until the end of it was Dr. Albert Speer, who wrote in his 1976 memoir, Spandau: The Secret Diaries, “The real importance of the air war consisted in the fact that it opened a second front long before the invasion of Europe. That front was the skies over Germany. The fleets of bombers might appear at any time over any large German city or important factory….

“Defense against air attacks required the production of thousands of anti-aircraft guns, the stockpiling of tremendous quantities of ammunition all over the country, and holding in readiness thousands of soldiers, who in addition had to stay in position by their guns—totally inactive—for months at a time.

“As far as I can judge, no one has yet seen that this was the greatest lost battle on the German side. The losses from the retreats in Russia—or from the surrender at Stalingrad—were considerably less.”

Added author Karl Roebling in his 1985 work, Great Myths of World War II, “Germany needed new models [of weaponry] but couldn’t produce them due to the bombings; periodic follow-up raids after Schweinfurt [the major ball bearings production center] would have put Germany out of business….

“When the European war ended, Germany lay in ruins—a ruination obvious to the eye. One source gives the following figures for Germany’s destruction: Hamburg, 75 percent; Bremerhaven, 79 percent; Frankfurt, 52 percent; Dresden, 59 percent; Kassel, 69 percent; Dortmund, 54 percent, and so on.”

Revisionists can speculate on “what might have been” (as I do here, granted) until the end of time, but in this case—and, indeed, in the same war—there is a concrete example to which one can point: the American war against Imperial Japan in the vast Pacific Ocean.

There, several enemy garrisons were simply bypassed, left on their island fortresses as the Allies leapfrogged over them to only those spots necessary as air bases from which to launch new and more costly offensives against the more important Japanese Home Islands.

Japan fell both as a result of the proposed two land invasions that never came as planned in Operations Coronet and Olympic, but instead via the dropping of the first two atomic bombs. The Americans had a third, and were prepared to drop as many as necessary (or available) in order to avoid any costly seaborne landings, of which bloody Okinawa had been the latest one.

We turn next to another question: could the D-Day invasion have failed?

Over the decades since the end of the War, there has come a certain feeling of the inevitability of the success of the epochal Allied invasion of Normandy that June 6, 1944— but it was by no means such a foregone conclusion at the time.

This was well realized by both the Allied Supreme Commander—General Dwight D. Eisenhower—and the German most involved in the plans to thwart it, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox” of former Afrika Korps fame.

Despite the vast and growing Allied experience with amphibious landings by spring 1944 in both the Mediterranean and the Pacific, their attempt to invade Italy at Anzio just the previous January had bogged down badly, leading to the resumption of the trench-style warfare not seen on a Western battlefront since 1918.

Could their next invasion have also failed militarily? The answer again remains a resounding yes, and for a variety of reasons. Churchill—who had authored the disastrous Gallipoli invasion of Turkey in 1915—had dual nightmares.

The first was that the Allied armada might be sunk en route to Normandy, and that thousands of Allied soldiers and sailors would simply drown in the English Channel—the very same body of water that had deterred Adolf Hitler’s projected 1940 Operation Sea Lion invasion of England.

From a naval standpoint, that armada could well have been wrecked in a storm like the one that later did strike, on June 19, 1944, and that destroyed or beached over 300 Allied vessels of all kinds, as noted postwar by General Dwight D. Eisenhower in his superb memoirs, Crusade in Europe.

Churchill’s second fear was a war of annihilation by the Germans once the troops were ashore. In 1940, the British Expeditionary Force had been chased off the Continent by German tanks and Stuka dive bombers at Dunkirk, a port city that remained in Nazi hands until 1945, well after D-Day.

The Prime Minister was wary of a repetition. The fear was justified, for that was precisely Hitler’s aim in both the German counterattack at Mortain in Normandy the prior August 1944 and then against the Americans in the Bulge, the largest single battle ever fought by the United States Army to this day.

Failing an outright second ejection from the Continent, Churchill—and most other top British commanders—had nightmarish visions of a costly war of attrition once ashore, and then inland, that would bleed the Allies white—just as had happened in the trenches of France on the Western Front in the Great War earlier.

That was as well not an unreasonable fear, either. The Germans had overrun France in 1940 in only six weeks, but it took the Allies four years later twice as long to cover the very same ground, despite the fact that Eisenhower—as a junior officer after World War I—had toured France during his work on the American Battle Monuments Commission between the wars.

Indeed, the Norman hedgerows stopped the Allied advance dead in its tracks for many weeks, which had all along been the very strategy of the German Commander-in-Chief West—Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the Wehrmacht’s senior ground leader—to beat the Allies with his armor inland, and then rout them back into the sea from whence they’d come.

Another factor uppermost in Ike’s mind was what would happen when the expected German secret weapon offensive was launched—and would it include atomic bombs? No one knew for sure, and as far back as the parachute landing in Scotland of Nazi Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess on May 10, 1941, British intelligence had known that the Jerries were indeed working on just such a war-winning super weapon. Would they use it now?

Thus, a key component of Allied planning was to get ashore as soon as possible to foreclose that dire unknown option, as well as to seize the launching sites of the new Vengeance-1 and V-2 rocket sites. One of the war’s most top-secret missions was that which cost the life of Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., older brother of a later president of the United States in the postwar age. JPK Jr.’s bomber exploded mid-air while heading inland to knock out one of those deadly launch sites.

Later, Ike would breathe a sigh of relief that Hitler didn’t assault with his rockets either the Normandy beaches themselves or the southern English ports of embarkation from which Operation Overlord was launched. The invasion might well have been defeated had that happened, he believed.

Since the war, some Western observers have felt that it was a cardinal error on Hitler’s part not to have done so, asserting that yet another blitz on London and other British cities (as well as on Antwerp) instead was a mistake, but they fail to grasp his reasoning at the time.

Seen in this light, the renewed terror bombing of the British Empire’s capital city was an attempt to force Great Britain out of the war altogether. The hope was that the Churchill coalition War Cabinet government might be toppled at last in the wake of the outcry over the renewed blitz using rockets instead of airplanes as in 1940—with more sophisticated types on the way (including the projected V-10, to bomb New York for the first time in any war.)

We must recall that the Prime Minister was, in fact, voted out of office by the British electorate at the end of the war in summer 1945, so this wasn’t an entirely forlorn hope on the part of the politically savvy German Fuhrer, either.

In addition, the former Chamberlain Cabinet had fallen in May 1940 with the success of that German victory on the Continent.

Then there were the Americans to consider. The American Army commander at Normandy, General Omar Nelson Bradley, admitted after the war that he briefly considered evacuating the men from Omaha Beach on Normandy, those of the veteran US 1st Infantry Division (Regular Army) and also the-then green Maryland-Virginia 29th Infantry Division (National Guard), once it seemed clear that the assault had bogged down on the beaches.

Had Bradley done so—or had the men been massacred—another attempt would not have been possible for some weeks, because of the nature of the Channel tides. An outright defeat might also have had serious repercussions on the then-upcoming U.S. Presidential election that November.

Politician Hitler was also well aware of this additional factor, and, unlike Franklin Roosevelt, didn’t have to stand for reelection in the Third Reich, no matter what happened. Washington insiders knew as well that FDR was already a very sick man who should not have run again in 1944, a medical fact known, too, by the then likely Republican Party nominee for President, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey.

Moreover, FDR’s top military adviser, General George C. Marshall, had already prevailed upon Dewey to exclude the Pearl Harbor disaster from the coming partisan political debate in the fall campaign. Dewey’s attitude on this and other such questions might well have changed in the fact and face of an outright Allied disaster either off or on Normandy, however.

Could President Roosevelt have been defeated for reelection in November 1944, six months after a D-Day failure? The possibility exists, and one has only to look at Lyndon Johnson’s withdrawal from the 1968 race in the wake of the Viet Cong Tet Offensive in South Vietnam for a parallel.

Interestingly enough, it was Dewey’s later protégé, Richard M. Nixon, who was elected in the end in 1968.

With both Churchill and FDR out of office, and Eisenhower disgraced over a debacle at Normandy, what then might’ve happened? The Germans would still have occupied all of France, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Denmark, Norway, and the Third Reich itself, with but a single enemy then to face—the resurgent Red Army in the East.

A second Allied invasion attempt would not have been politically feasible until the spring of 1945, with any element of surprise long gone. Could the Allies have invaded the Reich through the rugged Italian Alps instead?

Possibly, but the Germans had their superior Alpenkorps/Alpine Corps, the finest mountain troops on earth, while the U.S. had but a single such division, the still existing and celebrated 10th Mountain.

Churchill had all along opposed—right up until the actual landings of June 6, 1944—any Allied invasion of France from the Channel, preferring instead an assault in the Balkans to forestall a Red Army occupation of Central Europe.

By spring 1945, this, too, would’ve been a moot point, as that is exactly where the Russians stood, anyway. Thus, the end of the decade of the 1940s might well have seen either a firm German occupation of Western Europe still in place, a victorious Red Army there instead, or a combination of the two—as, indeed, was the case with conquered Poland during 1939-41.

Today, therefore, the capital of the United States of Europe might still be Nazi Berlin or Soviet Moscow, with either Hitler or Stalin ensconced in a magnificent tomb, celebrated as an enduring national hero.

That acclaim is already returning to Stalin in today’s modern Russia, and who knows what honors may befall the late Führer a century from now? History has a way of reversing itself, with Napoleon I and maybe even Kaiser Wilhelm II coming to mind.

In 1944, the Germans themselves believed that it was possible to defeat the Allied invasion, and Hitler was actually glad when the landings began, since he needed a resounding victory in the West to offset the steady string of defeats on the Russian Front from early 1943 onward.

He and his subordinate German commanders disagreed on where it would come and how best to defeat it, with the Führer leaning towards Rommel’s view that it must be beaten at the water’s edge within the first 24 hours, or their game was up. They were right, as it transpired, for two reasons.

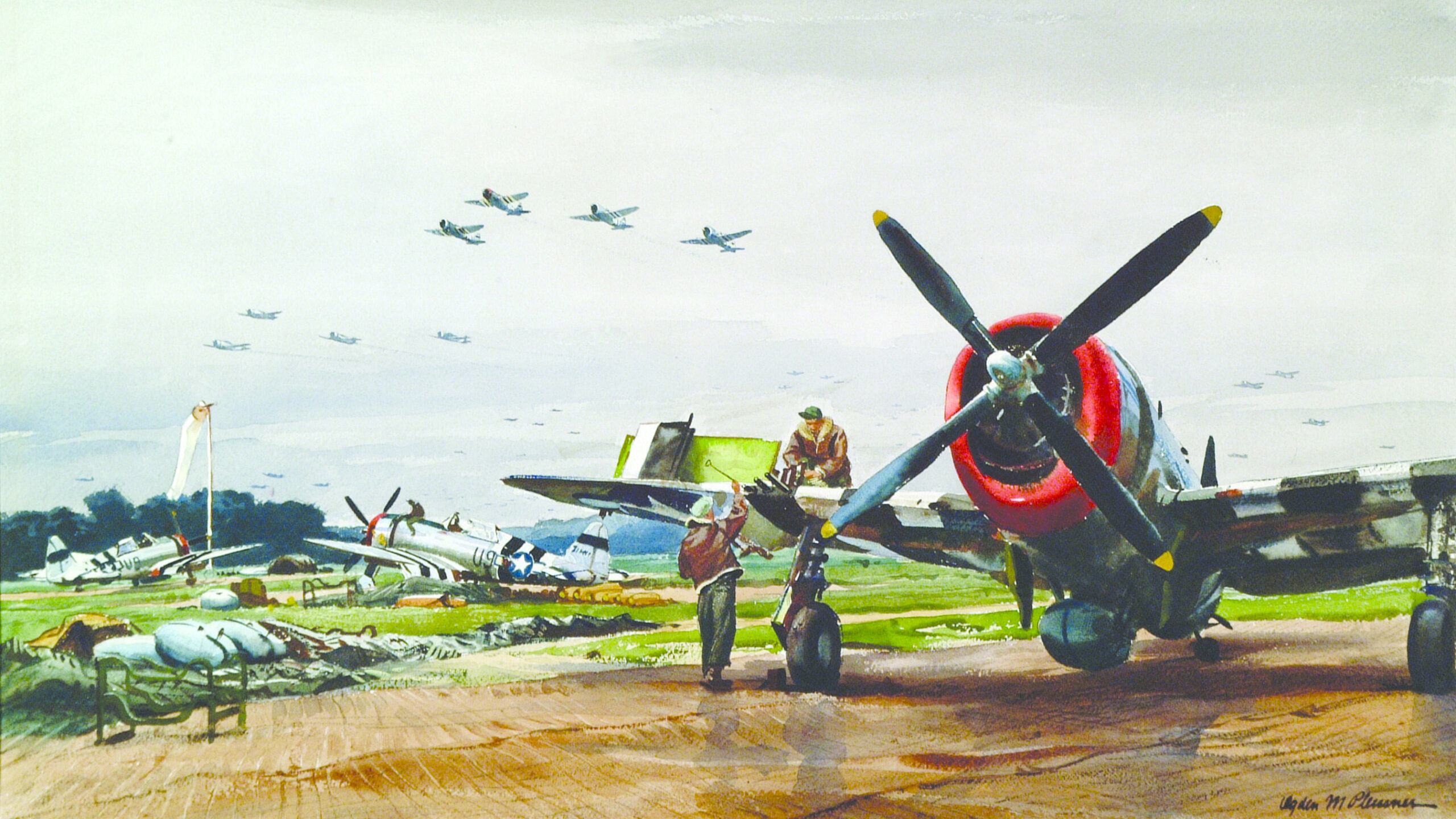

First, there was the complete Allied naval mastery of the choppy Channel, something that the Germans hadn’t achieved in 1940. Second was the total Allied control of the air, with the formerly vaunted German Luftwaffe already beaten and relegated for all practical purposes to the annals of aviation history.

Rommel had personally experienced Allied air power for over two years in both North Africa and then Tunisia. He argued that Allied air power would prevent the daylight movement to the invasion beaches of the Germans’ very best weapons—their superior new Panther and King Tiger tanks—and he was proven correct. In effect, Allied air power won the Normandy Campaign before it even began.

The bravery and tenacity of the men of the 1st and 29th Divisions and others at Omaha Beach—first in holding on, and then cracking it in a single day—Rommel’s Atlantic Wall cannot be overestimated. They got ashore and stayed—and it was no cakewalk.

Now let us look to those not present in Normandy: The Soviet Red Army juggernaut, then rolling relentlessly over every German force in its path.

One of the most cherished tenets of the history of World War II in the West is that it was the success of Operation Overlord—the massive and unprecedented amphibious cross-Channel invasion of northwest Europe—that broke the back of Nazi Germany, thus ending the war in the still-celebrated Allied victory.

But is this really the case, in either a military or a political sense? Did the vast Allied armada really sail from England to defeat the German Army in Nazi-occupied Europe, or was it actually to keep Stalin’s thundering Red Russian Army out of France and away from the Channel coast, where the Nazis had stood in 1940?

When Churchill congratulated the wily Soviet dictator at the 1945 Potsdam Conference for having taken Hitler’s capital, Stalin grunted, huffing, “The Czar got to Paris!” He was referring to the 1814 entry into the French capital by his predecessor as ruler of All the Russias, Alexander I.

In fact, throughout the later stages of the war, from the Battle of Stalingrad on, Churchill feared just such a development taking place. That was one major reason why he opposed the Overlord gambit from its inception, reckoning that France and the rest would fall to the West in any event when Nazi Germany surrendered, just as it did in 1945: Denmark, Norway, and Crete all without a shot being fired.

Churchill preferred a Western Allied thrust instead into the Balkans, a link-up with Yugoslavian Partisan leader Josip Broz Tito’s forces, and a drive on Bulgaria, Hungary, and Austria to keep the Red Army out of them all.

The American high command, however, refused to consider postwar grand politics until after its war was won militarily, and to it a cross-Channel invasion was the easiest and least expensive way to do that.

Thus, Stalin was handed politically intact the old Austro-Hungarian Empire of the fallen Habsburg dynasty; Poland, which Great Britain had gone to war to save in 1939; and half of the old Bismarckian Reich of the Hohenzollerns, an historic coup by any yardstick.

Stalin was well aware of Churchill’s attempts to throttle the almost stillborn Russian Revolution a generation earlier, when Allied troops had been sent to northern Russia to aid the counterrevolutionary White forces in defeating the Red Bolsheviks and restoring the deposed Romanovs to their lost throne.

He was fully cognizant as well that Churchill would do so again if he could and believed firmly that the Western Allies wished for nothing more than that Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany would tear themselves apart while the West looked on impassively, without cost to themselves. Why should they intervene while their enemies were destroying each other?

Stalin pressed Churchill at their Moscow summit conference in August 1942 for a so-called Second Front Allied invasion of Western Europe for late 1942 or spring 1943 to relieve pressure in the East on the then-embattled Soviets. Instead—in part to placate him—North Africa was invaded, at a time when the British had already beaten Rommel’s combined German-Italian forces at second El Alamein. Their test gambit at Dieppe had already flopped in 1942, moreover.

Still, the Western Allies did have in place a plan for an emergency French landing for 1943 should it become evident that the Red Army might be defeated, but this was scrapped after the stunning German debacle at Stalingrad in February 1943, followed by the even greater Soviet win in the greatest tank battle in history at Kursk the following July.

At that point—a full year before the first Allied soldier stepped ashore at Normandy—the Soviets had won the Second World War militarily, unless and until the Nazis deployed the atomic bomb first. New information has since revealed FDR wanted to drop an atomic bomb during the Bulge fighting if it had been ready. It wasn’t.

Stalin knew this, and then—and only then—consented to leave Soviet soil for the first time to meet personally with Churchill and FDR at the Tehran Conference in November 1943. Having already won the tank war, he no longer needed the Western Allies as he had before: rather, they then needed him to help win their war against Japan in the Far East to save their men’s lives.

Now the West definitely wanted to invade Western Europe, to prevent the coming Iron Curtain from extending to the shores of Normandy and Brittany, an actual possibility before the end of the decade of the Forties. In addition to that, Soviet battle fleets could be moved to the North Atlantic Ocean and English Channel.

Could Stalin have defeated the Nazis alone? All available evidence points to the affirmative at that late stage of the war. The Russians had taken Berlin in the days of Frederick the Great, and had no doubt that they would again, as in fact they did, along with Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Sofia, and Bucharest. Perhaps, then, both Brussels and Paris would also have fallen under their sway alone during 1945-46.

In addition, the Allies feared a second pact with Stalin that German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop wanted to sign, yet again, with his Soviet opposite number, People’s Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav M. Molotov, in 1943 as they had done in 1939; but an obstinate Hitler forbade it.

That, too, might have occurred had the Führer died in the bomb blasts of 1939-44, pushed by successor Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, always against all European wars because he had too much to lose.

The entire German High Command then believed that the war was lost, unless a political solution could be found whereby the Nazis would be allied either with the West against the East or vice versa—and there were rival factions within the top German leadership cadres, military and civilian, arguing both tacks. Hitler knew this.

At Tehran, Stalin foiled Churchill’s Balkan plans by standing fast with FDR, not only for the Normandy invasion, but also for yet a second invasion of France—Operation Anvil-Dragoon—which took place on August 15, 1944, and tied down what available forces the West then had in Europe, and thus away from the Balkans yet again.

The Germans knew all too well of the political dissension in the Allied High Command and counted on a political change of fortunes.

What the Nazis simply could not fathom was that the West would prefer their complete destruction to an anti-Soviet new Grand Alliance to keep the Red Army out of Central Europe; but that is what actually occurred—how the Second World War concluded—and the Cold War that both Hitler and Churchill correctly foresaw from differing perspectives both began and, alas, remained for the next four decades-plus.

There was a positive side to this equation, however: Stalin never got to Paris, nor did the tank treads of the Red Army grind to a wet halt at the water’s edge of the English Channel on the coast of Normandy, as Germany’s had in 1940.

Within a year of the end of World War II, the Cold War began.

Frequent contributor Blaine Taylor’s 23rd book is 2021’s illustrated volume Teutonic Titans: Hindenburg, Ludendorff, and the Kaiser’s Marshals & Generals, 1847-1955. In 1994, he published two completely different illustrated national magazines on the 50th anniversary of D-Day.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments