by Terry Gore

The Battle of Lewes was over, and with it the end of the actual power of the English king, Henry III. As the vanquished king stared in mute silence at his rebellious nobles, led by his brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort, he no doubt wondered where God’s will was that day, May 14, 1264. Henry and his two sons were prisoners. For all intents and purposes, the Barons’ War was over, and Simon de Montfort now ruled England.

The actual military campaign had lasted scarcely a year, with numerous truces and arbitrations, but in the end, all had been settled in the morning battle at Lewes. Yet, though Simon seemingly held most of the power in England, it was not as solid a situation for him as it first appeared.

The Papacy, very powerful in the 13th century, certainly did not support the usurpation of the king’s power. Matthew Paris duly noted Papal displeasure with the English clergy when he wrote, “[The Pope] had no bowels of affection for England.” The concept of Absolute Monarchy was supported by the Papacy and any revolt against this institution curried only animosity from Rome.

“Free the King!”

Many considered the victory at Lewes “divinely inspired” and Simon’s victory a triumph of the English over “foreigners,” meaning the King’s relatives and Continental supporters, overlooking the fact that Simon himself was a Frenchman. In any event, riding the tide of triumph, Simon did what he could to destroy any Royalist opposition. But he could not quell it altogether, and Royalist resistance remained obstinate. If anything, the capture of the king along with the heir to the throne, Prince Edward, gave the Royalists a rallying point and a war cry: “Free the King!”

Opposition to the baronial success was especially strong along the Welsh border, where the marcher nobles had plenty of strength and local support—and they did not care in the least for Simon de Montfort. Two of these nobles in particular, Roger Mortimer and Roger Leyburn, had both fought at Lewes and escaped capture, taking with them some prisoners of their own and remaining defiant in their strongholds. Other Royalists had also been allowed to go free after the battle, but they owed little to Simon and still held onto their castles in the name of King Henry. Many others had determined that England no longer remained a healthy environment for them and had fled to France. They gave the French monarch King Louis a biased report on the rebellion, causing him to make plans of his own to deal with the English “rebels.”

During the summer of 1264, Simon attempted to deal with his enemies before they could become even more powerful. In July, with his ally Prince Llewelyn of Wales, he quickly moved and captured a number of Royalist castles, but could not complete his campaign in time as another serious threat appeared to his tenuous hold on power.

Queen Eleanor, Henry’s wife, who had managed to escape to France, attempted to raise a Continental army to invade England and take back the throne. She raised troops from a variety of regions to join her bands of disaffected Royalist exiles. But Simon had good intelligence in France and gathered his forces to oppose the expected invasion, leaving the Royalist marcher lords alone for the time being. The Flores Historiarum reported that “such a multitude gathered together against the aliens that you would not have believed so many men equipped for war existed in England.” Yet, the English mobilized because they had a cause to fight for. They unified to prevent a foreign invasion and their own destruction if they lost. By October, however, the threat of invasion ended when Eleanor ran out of money and the invasion plans died for lack of funding.

Simon Calls for Parliament Meeting

As the end of 1264 approached, Simon seemed quite well ensconced and called for a Parliament to meet on January 20 to arrange terms for freeing the captive Prince Edward. Militarily, the barons had done well. In a quick campaign that year, Simon had managed to catch a number of the Royalist marcher lords between Llewelyn’s Welsh forces and the baronial armies. They were forced to agree to terms, giving up their lands to Simon to hold for them as they were exiled to Ireland for a year. In exchange for this, it was agreed that Prince Edward would be released, though not yet. As the Flores Historiarum noted, “Fortune smiled on all that he [Simon] had conceived.”

The quick campaign had proved de Montfort’s generalship to be superior, as he was able to raise armies, move them quickly, work out alliances, and impose his will on the enemy. Still, things were not as they may have seemed. His rival armies in England caused much destruction as they roamed about the countryside, the Flores Historiarum noting that when the Royalist armies moved from place to place, they brought with them pillage, killing, and arson. Personal feuds had not ended with the baronial victory either. There would still be much suffering in the months ahead for commoner and noble alike.

Simon and his family profited greatly from his victories. Not one to waste an advantage, Simon used his increased wealth to buttress his military strength; the Flores Historiarum notes that by Christmas, he had with him at his bastion of Kenilworth 140 household knights, a number unmatched by any 13th-century English monarch. Such a large household assured him of a secure force with which to wage war if it came to that once again.

Alienating His Allies

At the end of 1264, Simon felt secure enough to prepare to free his royal prisoners, but he made one fatal mistake. As the Song of Lewes reads, “He would set before him the advancement of his friends, would aim at the enrichment of his sons and would neglect the safety of the country.” Instead of rewarding his followers to ensure their continued loyalty, Simon took castles, ransom, and lands from his enemies, for himself, his family, and his close friends, alienating his allies in the process.

One of Simon’s younger supporters, the 22-year-old Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, defected to the Royalists, carrying with him both anger and avarice. Simon seethed about the defection, but waited until April 1265, then gathered his forces along with the captive King Henry and Prince Edward and marched to Gloucester to deal with his former ally.

The Earl of Gloucester thwarted capture, so Simon opened up a dialogue with him, attempting to alleviate the marcher rebellion by negotiation. In the meantime, two of the Royalist leaders, John de Warenne and William de Valence, landed with a small force on the west coast of Wales to raise the banner of rebellion against the baronial forces, supporting the King and Prince Edward. Simon duly moved his forces to the town of Hereford to counter them.

On May 18, Prince Edward took advantage of a lapse in his “protective custody” and escaped from the clutches of the baronial army; this would prove decisive in the upcoming campaign. The 26-year-old Edward, who was both Simon’s nephew and godson, had help from a number of knights under the marcher lords Roger Clifford and Roger Mortimer. The escaped prince wasted no time in joining forces with de Clare and the marcher lords. The Royalists once again had a military leader as well as a rallying point.

Prince Edward Mounts Military Campaign Against His Uncle

Prince Edward met with de Clare at Ludlow and swore to him that he would “maintain the good charters and customs, to expel the aliens and to admit none but Englishmen to (his) counsel.” No doubt he wished to mollify any nobles who would be dubious of his intent and leadership. It took only a month or so for Prince Edward to mount a military campaign against his uncle Simon.

Castles and towns fell or surrendered to the prince until he ran up against Worcester, which he decided to besiege. Simon, angry at his own men for allowing Prince Edward to escape in the first place, took his army and attacked de Clare’s lands, allowing his ego and desire for revenge to override common sense. He moved into Wales ostensibly to raise more troops. This was an extremely bad idea because the baronial English army accompanying Simon remained wary of the their traditional enemies, the Welsh, and the land they had moved into was a poor provider for an army that soon found itself hungry and increasingly frustrated.

Simon soon realized his predicament. He was in unfamiliar territory and virtually surrounded by hostile marcher lords. He sent an urgent message to London, ordering the Bishop of London to immediately excommunicate any “rebels and traitors” along with Prince Edward, de Clare, de Warenne, and any other Royalist supporters.

The town of Gloucester, meant to be the baronial escape route across the Severn River, had been reinforced with 300 baronial men-at-arms. Simon took control of the town in order to move back into friendly lands, and to escape the marcher lords and Prince Edward. Unfortunately for Simon, Prince Edward also knew of the strategic advantage of Gloucester. He isolated and captured the town, forcing the vastly outnumbered and dispirited garrison to surrender when Simon refused to march to their aid. This was another huge tactical mistake—or was it?

Perhaps Simon felt he could not face the Royalist forces now gaining strength and morale with the charismatic Prince Edward as their leader. His own army seemed increasingly resentful, hungry, and demoralized. At any rate, by leaving the town of Gloucester to its fate, Simon had to find a way back into England. It was now late summer and the Royalists were gaining strength daily.

Equalizing the Military Situation

Simon did what he could to equalize the military situation. He met with Prince Llewelyn of Wales and received a force of 5,000 Welsh spearmen to bolster his dwindling army. He then attempted to cross the Severn River into open territory by gathering transport ships, but Prince Edward’s spies found out about the plan and thwarted it by destroying the ships before they could be used. Simon now seemed truly cut off from his allies, friends, and supplies. He had also run out of funds—a bad situation with an army expecting to be paid for its service.

Simon had earlier sent a message to his son, Simon the Younger, who was camped with his army at Pevensy, near Hastings, ordering him to come immediately to his aid. Simon the Younger duly moved from his camp, but first went to London, spending several days there before marching on to Winchester, where his men massacred a group of Jews. Simon the Younger then moved on to Oxford to raise more men. As Simon the Younger’s army marched west, it managed to pick up numbers of reinforcements—so many, in fact, that he felt quite safe. Finally, a full month after he had been summoned, he arrived in Kenilworth at the end of July.

An amazing amount of intelligence is reflected in the ensuing campaign of late summer 1265. First, Edward received word of Simon the Younger’s arrival at Kenilworth. He duly pulled up stakes and went after him, figuring to destroy this army before it could join up with the elder Simon’s forces.

“Get Up … and Come Out, You Traitors!”

Kenilworth castle afforded the young Simon a very good defensive position, but he overconfidently and foolishly allowed his men to avail themselves of the comforts of the town’s various taverns and houses. Young Simon partook of the amenities as well. Rumor had it that Prince Edward had a spy with the baronial army who made his way to Edward and told him of this poor defensive situation.

Early in the morning of August 1, Edward force-marched his army during the night, a difficult thing to do in any era, but he wished to attack the baronial army as it slept. The attack was wildly successful—the Chronicle of Melrose tells us that Prince Edward’s troops “raised a very loud noise … and armed men [were] shouting horribly at [the baronial forces] saying, ‘Get up … and come out, you traitors and servants of the worst and most obstinate traitor, Simon, for by God’s death you are all dead men!’”

Young Simon’s men were caught by surprise. One can only imagine the terror of being attacked while asleep, waking to find flashing bloody swords in the din and the flickering firelight. Many were killed outright while others quickly begged for their lives and were captured, but young Simon and a large number of men managed to make it back into the castle. Being nearly naked, they outran their armored attackers, leaving behind their armor, horses, supply wagons, and banners—items that were taken by Prince Edward’s men.

As the captives were paraded before the victorious Royalists, de Clare made it his business to rectify insults that had been directed at him for his earlier defection from the baronial alliance. At least one captured noble was beheaded. What Edward thought of this is not recorded.

Simon the Elder Marches Toward Army of Simon the Younger

What Simon the Elder knew of any of this, no one really knew, but he did have intelligence sources reporting to him that Edward’s army had departed from its position guarding the river crossing. Gathering his own troops together, as well as the thousands of Welsh spearmen now accompanying him, Simon made an uncontested crossing of the Severn and marched toward his son’s army in Kenilworth—Rishanger’s Chronicle puts the crossing spot at Clive.

It did not take long for messages to reach the baronial army telling of young Simon’s situation. Not wishing to engage the enthusiastic and superior Royalist army with his own army in its present condition—hungry, demoralized, and shrinking by the hour from desertion—Simon moved toward the town of Evesham, arriving there on August 3 or 4.

Prince Edward’s scouts and spies continued to be busy. They reported that Simon’s army had crossed the Severn and was moving toward Evesham. Not wanting to waste time and energy in dealing with another siege, Edward took his captives and the captured banners, left Kenilworth, and moved toward Evesham, again by a night march. He wanted to destroy Simon’s army before it could unite with the remnants of the younger Simon’s forces.

Simon Exhausted, the Baronial Army Trapped

In 1265 the town of Evesham lay within a loop of the Avon River, with only a single bridge across the river. Arriving there, Simon, almost 60 years old, had to be close to mental and physical exhaustion. His usual brilliant tactical intelligence lapsed as he set up camp during the night and morning of August 3 and 4 in the bend of the Avon—not on the high ground with its tactical benefits, but below it, exposed and open to attack. The baronial army was trapped.

As Prince Edward’s scouts reported the location and disposition of Simon’s army, the prince moved swiftly to contain it. He ordered a force of mounted troops under the command of his friend Roger Mortimer to cut off Simon’s potential escape route from Evesham. He then arrived with his main forces in the early morning, found the high ground indeed vacant, as had been reported, and so formed his army up on the crest of Green Hill, two miles from the town and Simon’s army. Using the tactical guile that had so far guided him to victory, Prince Edward unfurled the banners captured at Kenilworth, including those of Simon’s son and allies.

Unaware as yet of his dire situation, Simon prayed on the morning of August 4, before having his cavalry mount up and his troops—all of them weary and eager to return to friendly lands and home—begin to march out of town. The townspeople lined up along the streets to watch King Henry and Simon as they left. Suddenly, a scout reported that armed cavalry was approaching from the north bearing the banners of Simon the Younger and the barons who had gathered at Kenilworth.

“We Are All Dead Men”

Walter of Guisborough wrote that Simon’s barber, watching from a church belltower, yelled down to the nobles below, “We are all dead men, for it is not your son, as you believed.” The chronicles tell us that Simon then cried out, “May God have mercy on our souls, for our bodies are theirs.” The monk Thomas Wykes, a contemporary chronicler, wrote that when Simon saw two separate armies facing him on Green Hill, he asked who commanded them. “It is Edward’s army” was the answer. “And the other?” “It is Gloucester.” “The traitor!” said Simon, “I see clearly today I shall die.” Elation had turned to gut-wrenching fear as the baronial fighting men saw the banners of de Clare and Prince Edward. Simon also faced the dread reality that his son was either dead or a Royalist prisoner.

The numbers of combatants favored the Royalists; they had perhaps 8,000 men to Simon’s 6,000, the latter including many Welsh foot of dubious quality. But did Simon really have no choice but to fight his way out? Because he controlled the town of Evesham and its supplies, he could have stalled for time in order to allow reinforcements to reach him. Was his mental state completely distraught due to dread of his son’s fate? Or did he rather fear the duplicity of Prince Edward and de Clare if terms were offered? Whatever the reason or reasons, Simon prepared to do battle.

The two Royalist divisions on Green Hill began to move and Simon, noting their advance, said, “By the arm of St. James, they come on well … they did not learn that from themselves but from me.” When he sighted de Clare’s personal banner, he yelled, “This red dog will eat us today,” and turning to his son, Henry de Montfort, told him, “Your presumption and the pride of your brothers has brought me to this end.”

Simon’s Tactical Battle Plan

Although outnumbered, Simon did conceive of a battle plan, if not to win, then at least to escape. He formed up his army with his heavy cavalry in front, followed by his loyal English foot and the Welsh at the very rear. He planned to use a single column of attack and attempt to smash his way through the vulnerable junction point where the two Royalist divisions met. All things considered, it was a sound tactical plan because the juncture of two commands is a weak point of any army, units often fighting close by but not coordinated or supportive of each other.

As Simon broke into his charge, the weather took a decided turn for the worse. Dark clouds covered the sky, signs of an imminent storm. Prince Edward’s army, moving down the hill in a charge as well, now shouted “Death to the traitor!”

As the ranks of armed opponents closed upon each other, there was an initial excitement and flow of adrenaline, augmented by alcohol in not a few to temper the fear of facing serious wounds or death. For men on foot the most awesome dread—a primal fear—was being attacked by mounted knights. Medieval leaders often did what they could to alleviate this fear, providing the foot with cavalry-defensive weaponry—long spears, long-handled axes, and pikes. The foot would also be packed into tight formations, close together to give them a sense of strength in numbers as well as the reassuring morale-building qualities of feeling protected to both sides and rear.

In previous times, such formations were referred to as “shieldwalls”; men would overlap their shields to present an unbreakable barrier to charging cavalry. Would horses charge into a solid line of men? Some military historians argue that they could be trained to do this while others say no. Yet time and again, reports are illustrative of cavalry breaking through foot. Perhaps this is a result of the psychological impact of standing to receive a charge as opposed to doing the charging. There is an obvious advantage to the attackers as they are the ones with the initiative and the ones who strike the blow.

Armor, or lack of it, also could be a factor in whether men stood to fight or ran in fear. Armor gives the wearer the psychological advantage of feeling secure. Yet with the increase in armor came an increase in weapon size and weight as well to negate the protection of the armor. For the thousands of men at Evesham that day, all of these factors weighed in.

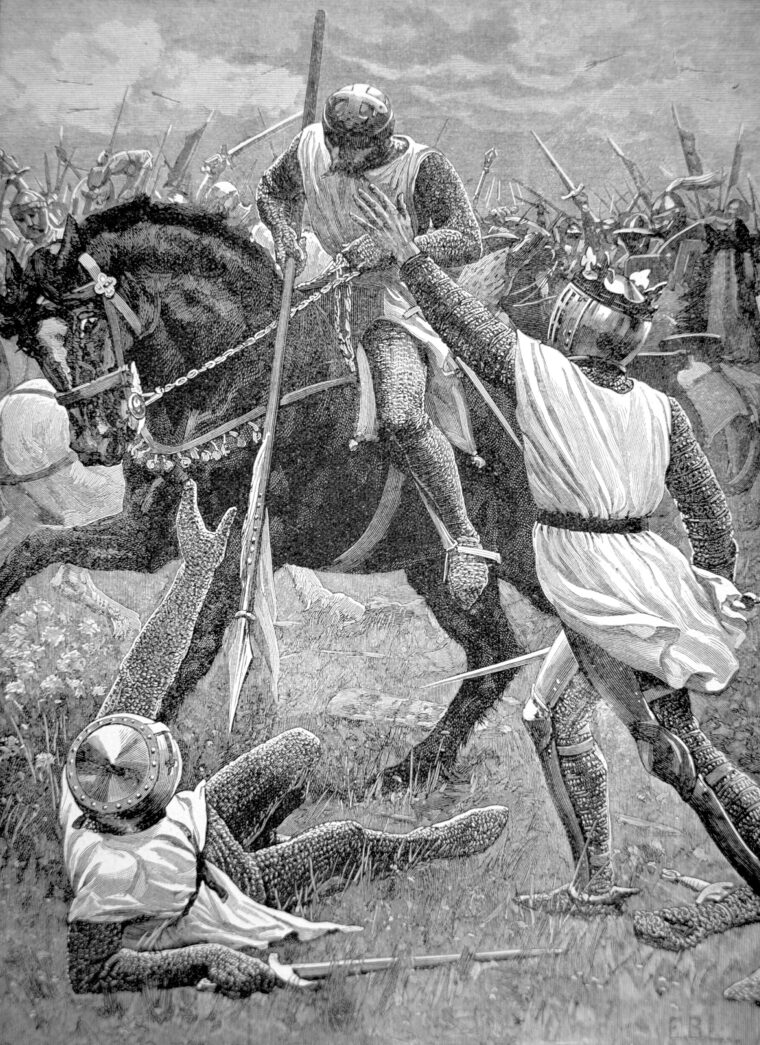

To Pay a Heavy Price

At first, it appeared that Simon and his front ranks would succeed and they broke through the Royalist ranks. But then Simon’s horse was killed, pitching him to the ground. His sons Henry and Guy, along with the rest of Simon’s loyal retainers, rode to his defense rather than making their escape. The loyal bodyguards neither expected nor asked for quarter. They would stand and die by their liege lord. The baronial forces had done their best, but the shock of contact had failed to break completely through the ranks of the Royalists. Now they would pay a heavy price.

Due to the way the armies had been initially formed up, Prince Edward and de Clare’s divisions outflanked the baronial army. Edward had carefully watched the baronial column until it made contact and then ordered his own troops to wheel into the exposed flanks. This was not easy, because knights had a tendency to wildly charge once the enemy came within range, but the prince managed to keep a tight rein on his troops, a mark of his leadership ability.

The Welsh infantry, seeing Royalist cavalry swooping down upon them and being both unarmored and without anti-cavalry weapons, let their basest human instinct for survival take over. They turned and broke for the rear, trying as best they could to dodge the lances and swords of the Royalist horsemen. This was not their fight anyway.

“Such Was the Murder of Evesham, for Battle It Was Not”

The baronial English foot and cavalry fought hard—they realized that failure meant death or at best captivity. Ransom was preferable to simply killing, at least for a rational man. In the heat of battle, however, rationality is often forgotten. Brutal fighting raged, with Robert of Gloucester noting: “Such was the murder of Evesham, for battle it was not.” Deadly weapons dealt horrific wounds, splintering arms and legs, shattering shoulder blades, and cleaving skulls. Standing in the midst of such carnage tried the courage of even the bravest warrior.

King Henry had been placed in a position where his own followers soon were closing in on him. The Melrose Chronicle noted that Royalists, thinking him a member of the baronial army, threatened his life. To this Henry shouted out, “Do not hit me, I am too old to fight,” and “I am Henry … your king! Do not harm me!” His pleas were heeded.

Elsewhere the fighting intensified around Simon and his sons. Suddenly one of the sons, Henry de Montfort, was struck by an enemy lance and toppled from his horse. Seeing his son thus felled, Simon said, “Then it is time for us to die.” Still, the old leader fought on as his knights died around him, some 30 to 60 of them, depending on the reports—a very bloody toll in an age of ransom and capture. Yet there were many old enemies fighting on opposite sides. There is no war so brutal and cruel as a civil war when one is fighting for ideology and belief, not just for land or loot.

The Mutilation of Simon

There was never any real doubt as to the outcome of the battle; the day was going against the baronial army. The fates frowned on Simon’s personal struggle as well. His age had taken its toll and his ability as a warrior had eroded over the years. Fighting for his life, he took several wounds. Finally, the loss of blood caused him to falter, and once he fell, his enemies were upon him with a vengeance. His body was fought over, but the Royalists eventually wrested it from the dwindling band of loyal baronial retainers. According to the visual evidence of the Flores Historiarum and contemporary reports, the corpse was stripped of its armor and clothes; the head, arms, and legs as well as the genitals were hacked off; and the mutilated trunk thrown to dogs.

Simon the Younger and the troops that continued to follow him appeared from Kenilworth too late to save the baronial army. Wykes noted that de Montfort’s son did see his father’s head hoisted aloft on the point of a Royalist pike as it was triumphantly paraded as a trophy of war. The effect of such a sight on the young knight can only be imagined.

Simon’s son Henry died in the fighting, but another son, Guy, managed to survive his wounds. Prince Edward granted him his life while monks from Evesham mercifully gathered what parts of Simon’s body they could find and took them into a church. Although reportedly wounded by an arrow, King Henry joyously rejoined his son. On the field of battle lay 4,000 dead out of a baronial army of only 6,000.

Lessons Learned for King Edward

The lessons learned from Evesham would serve Edward well when he was crowned King Edward I in 1272. His tactical and strategic sense as well as his ability to inspire and lead men to victory would be vital during his tumultuous reign.

Simon’s year of virtual rule in England came to an abrupt end for many reasons, not the least being his reliance on his sons. Simon left so much wealth and power in their hands that animosity and jealousy arose among his previous allies, most notably de Clare, turning them into enemies. In addition, Simon’s failure to subdue the marcher lords allowed Edward a ready-made base of power for his assumption of leadership over the Royalist forces.

In 1918, a cross was erected at Simon de Montfort’s burial site, and on each Sunday that falls nearest the anniversary of the Battle of Evesham, services are held there. Although Simon’s revolution and rule are still controversial, his resolve in bringing a political voice to more people is remembered today.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments