By Nathan N. Prefer

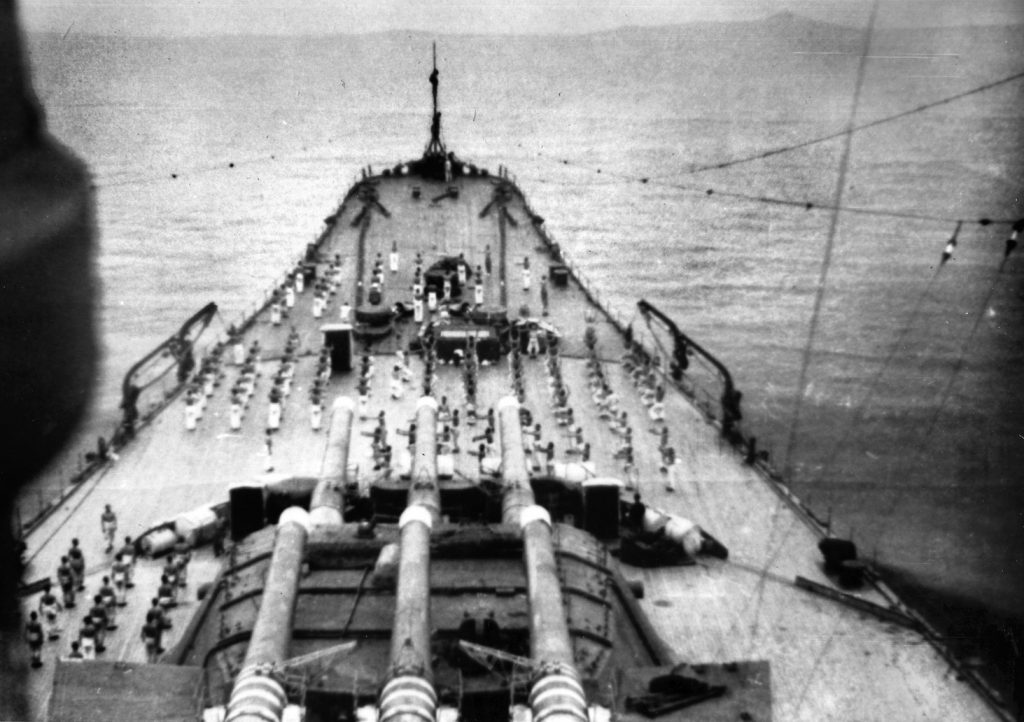

It was the largest warship ever built up to that time. It carried larger guns than any warship before it. This pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was named after Japan itself, IJN Yamato, the historic name for Japan. Yet in its brief career, it accomplished nothing of importance and was sacrificed in the final destruction of Imperial Japan and its kamikaze (“Divine Wind”) hysteria.

The roots of the IJN Yamato and its sister super-battleship IJN Musashi can be traced back to the introduction by the British Royal Navy of the HMS Dreadnought in 1905. The British battleship made all others obsolete and started many navies, including the Imperial Japanese Navy, on a search for a bigger and better battleship. They first appeared in 1909 and were followed by several more in the following years. By 1916 the latest IJN battleship, the IJN Nagato, was armed with 10 16-inch guns, the largest afloat at the time.

By the twenties, Japan was trying to build a fleet to equal, if not in numbers, then in power, that of the United States. Treaty obligations kept the number of its capital ships limited to 70 per cent of those of the United States. The Japanese concentrated on quality rather than quantity, and built their ships designed for combat against a superior force. When, in December 1934, Japan decided to renounce the Washington Naval Treaty that had limited its fleet, it immediately moved to increase the numbers of its fleet.

Part of the new naval policy of Japan was to build in secret four new super-battleships. These were to carry 18-inch main guns and enough armor to withstand hits by 18-inch enemy shells. The first two of these ships, the Yamato and Musashi, were approved in 1936 and the remaining two in September 1939.

Planning for the construction of these ships began in the fall of 1935. More than 20 designs for the ships were considered and discarded. The naval architects were charged with planning a ship that could carry nine 18.1-inch main guns, have enough armor to withstand 18-inch shellfire from an enemy, and have enough underwater armor to prevent damage from a torpedo carrying a 660-pound warhead, while having a top speed of 27 knots and the ability to cruise 8,000 miles at an average speed of 18 knots. The designers finally decided that to meet all these requirements the ship would have a displacement of 69,000 tons.

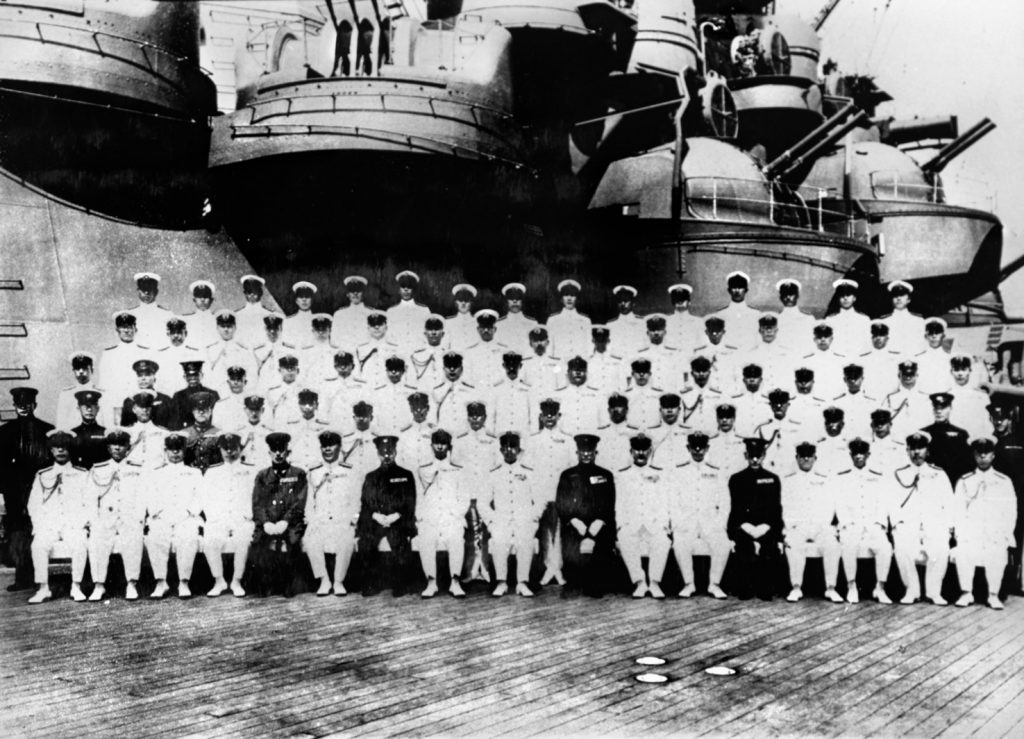

Indeed, so large were these ships that the dockyard and channel at Kure, Japan, where the Yamato was built, had to be deepened before construction could begin. Similarly, before Musashi could begin at the Mitsubishi docks in Nagasaki, the facility had to be extended over 50 feet into the hillside. Security was tight and effective. United States Naval intelligence acquired no information regarding the two ships, and complete information eluded them until after the war.

In 1939, even as the Yamato and Musashi took shape, the third ship of the class, tentatively named the Shinano, was begun. But the Pacific war had already pointed out that the primary naval weapon of that war was no longer the battleship, but the aircraft carrier. Accordingly, the Shinano was converted mid-construction to an aircraft carrier. The fourth planned ship was neither named nor completed when it was scrapped in November 1941.

As expected, these ships were huge. They had a beam of 127.7 feet and a length of 863 feet. Fully loaded, the battleships drew 34.5 feet of water—so deep that several Japanese naval bases had to have their harbors dredged to allow the ships to dock there. Armor protection was concentrated over the engines, magazines and essential machinery. In total, the ships’ armor weighed over 22,000 tons.

Propelled by four geared turbines powered by 12 steam boilers, the ships boasted 150,000 horsepower. This provided the required 27.5 knots speed as planned. The latest damage-control features were built into the ships, as well. They could withstand a list of up to 20 degrees without capsizing.

Events were to prove, however, that there were serious weaknesses in the design. The armor was concentrated over vital machinery and ammunition spaces, leaving the bow and stern sections unarmored and vulnerable. The internal pumping system was inadequate to compensate for major flooding in those two areas. There was also a weakness between the upper and lower side armor belts, which would, if hit, defeat the armor protection of the ship.

Finally, the torpedo protection was, for some reason, inferior to that of other navies’ protection. Combined with the wartime American innovation of a more powerful explosive, Torpex, this made these ships unexpectedly vulnerable to torpedo attacks.

But Yamato and Musashi could also strike hard at any enemies they encountered. In addition to the unequaled 18.1-inch main guns, there were a dozen 6.1-inch guns for antiaircraft protection. Another dozen 5-inch guns were also designed for antiaircraft use. Finally, there were two dozen 25mm antiaircraft guns and machine guns for close-in antiaircraft protection. To scout out an enemy force, the ships carried from four to seven scout aircraft, which could be launched from either of the two catapults located on the quarterdeck.

But the main, and most feared, feature of the super battleships was their main guns. These monsters each weighed 162 tons and, with their base and rotating equipment, topped out at an unprecedented 2,774 tons each. The shells they fired each weighed 3,219 pounds and could be launched at the rate of one-and-a-half per minute.

These were the premier ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Neither had major modifications during the war, other than to have radar installed and antiaircraft mounts improved and increased. In 1943, while in drydock for battle damage repairs, Musashi had depth-charge rails installed on her stern.

The Yamato joined the fleet on February 12, 1942, and was immediately selected as the flagship of the Commander, Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. She completed her trials on May 27, 1942, and sailed a few days later for the Midway operation. There it remained with the supporting fleet as the flagship and saw no action.

In August 1942, the ship was stationed at Truk as a headquarters ship. This began a long period of inactivity which earned the ship the sobriquet of “Hotel Yamato” for its housing of senior officers.

After nearly a year at Truk, the Yamoto returned to Japan for a refit, then returned to Truk. There it undertook some transport missions, and it was while it was on one such mission that she was attacked by the USS Skate (Lt. Comdr. E. B. Mckinney). The American submarine fired four torpedoes, one or two of which hit the Yamato on the starboard side near the Number Three turret.

These hits revealed the weakness between the upper and lower armor belt on the Yamato, causing a failure that allowed 3,000 tons of water to enter the ship and flood the Number Three turret’s ammunition magazines. Damaged but not badly hurt, the battleship returned to Truk for emergency repairs before going on to Japan for final repairs in January 1944.

Left behind at Truk was the sister ship, Musashi. She had been commissioned on August 5, 1942, and left Japan January 18, 1943, arriving at Truk four days later, where it assumed the duties of flagship from Yamato. When the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Yamamato, was ambushed and killed by American aircraft, Musashi was chosen as the ship to return his ashes to Japan, where the Japanese Emperor paid a personal visit to the ship.

Musashi then returned to Truk, where she remained until October 1943, when she sailed as part of a task force to defend against a suspected American attempt to retake Wake Island in the Central Pacific; Musashi then returned to Japan in February 1944.

After a brief stay, she transported two infantry battalions to Palau Island and remained there for the next month. Leaving to avoid an incoming air raid, Musashi was struck by one of six torpedoes fired by the USS Tunny (Lt. Comdr. J. A. Scott). The American submarine’s torpedo hit the battleship near the bow, causing a 19-foot hole and flooding the ship with 3,000 tons of water. Musashi was forced to head to Kure in April 1944 for repairs and then joined her sister ship at Lingga Roads harbor, near Singapore.

By this point in the war, the American advance up the coast of New Guinea was worrying the Japanese High Command, and the recent American invasion of Biak Island, off the New Guinea coast, was only the latest threat to Japanese bases there. In this latest invasion, the Japanese command believed that the decisive battle for which they sought so long was near.

Although the Imperial Japanese Army had decided to leave the Biak Island garrison to its fate, the Imperial Japanese Navy saw decisive battle opportunities and so ordered the implementation of Operation Kon. The new Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, decided to take the opportunity to strike at what he believed was a major portion of the American fleet.

Operation Kon included the transportation of 2,500 troops of the 2nd Amphibious Brigade from Mindanao to Biak in warships. Rear Adm. Naomasa Sakonju, aboard the cruiser Aoba, was in command with another light cruiser and three destroyers carrying the troops. The older battleship Fuso, two heavy cruisers, and five more destroyers were the covering force for the landing. Naval aircraft would also cover the landings.

But Admiral Sakonju’s force was soon sighted by American submarines and aircraft. Hoping for surprise, the Japanese force also received reports—incorrect, as it turns out—of an American aircraft carrier in the vicinity. Admiral Toyoda suspended the entire operation.

But Japanese reconnaissance soon reported that there was no aircraft carrier supporting the Biak landings, and that there were only a few American and Australian cruisers as heavy support for those landings. Admiral Toyoda ordered a renewed Operation Kon. This time, six destroyers would carry troops and pull barges loaded with troops protected by two cruisers. But once again, after American aircraft sank one destroyer, reports of a large American task force in the area caused Admiral Sakonju to retire.

These failed attempts to reach Biak Island convinced Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, commanding the Japanese Mobile Fleet, to launch a determined effort to relieve Biak Island. With Admiral Toyoda’s permission, he launched Operation A-Go. This time, major Japanese fleet units would participate. They included the Yamato and Musashi, as well as three cruisers, three destroyers, and a transport unit with two additional cruisers and four destroyers.

The force assembled at Batjan on June 11, 1944, and prepared to sail for Biak on June 15. The plan was to land the reinforcements and bombard the American beachhead. But just as plans were being made, news arrived of American carrier-based air strikes against Guam, Saipan, and Tinian in the Mariana Islands. Clearly, the main American fleet was in the Mariana Islands, not off the coast of New Guinea. Operation Kon was suspended, and Operation A-Go was directed to the Philippine Sea, near the Marianas.

The two super battleships and their escorts were ordered to rendezvous with the rest of the Combined Fleet in the Philippine Sea. The result was the Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19-21, 1944), in which the opposing surface ships never engaged one another. The entire battle was fought by the aircraft of either side. It was a lopsided victory; the Japanese lost 346 aircraft and two carriers, while the Americans lost 30 aircraft and had one battleship damaged.

With the Japanese defeated, the Americans pursued, destroying two oilers and another aircraft carrier, while damaging a second. In all these battles, neither the Yamato nor the Musashi were damaged. They returned to Lingga Roads in July 1944.

It was the American invasion of Leyte Island in the Philippines that finally provided the decisive battle that the Imperial Japanese Navy had sought for so long. Responding to that landing, the Japanese Navy sent against the Americans several task forces that were intended to gain entrance to Leyte Gulf and destroy the American landing ships and equipment there.

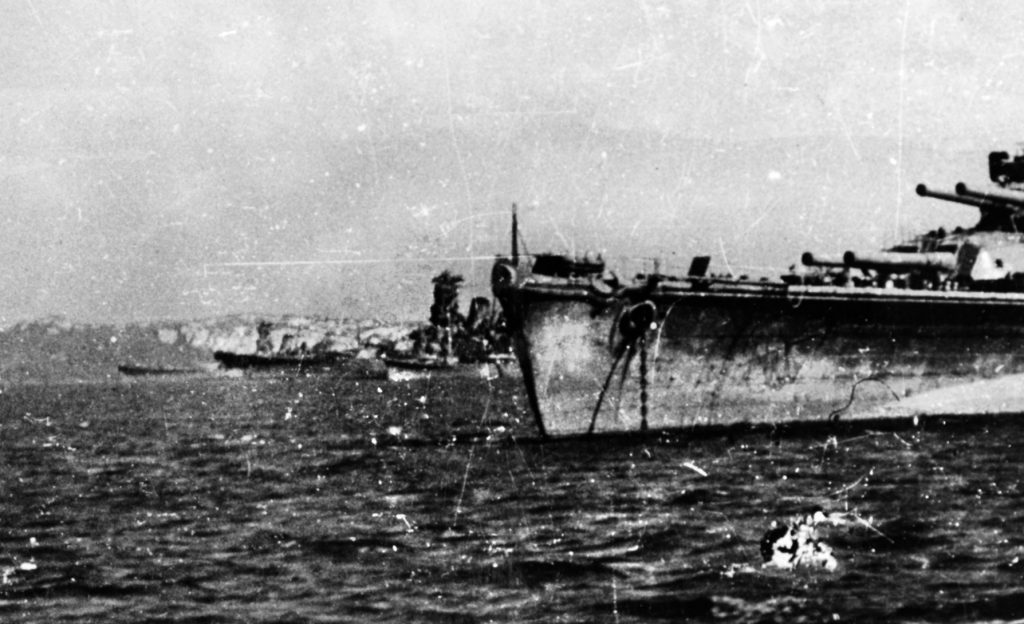

Both the Yamato and Musashi were a part of “Force A,” or Center Force, under Admiral Takeo Kurita, whose mission was to transit the San Bernardino Strait, join with “Force C”, or Southern Force, and catch the American amphibian armada in a pincer between them.

As did all the Japanese task forces, Admiral Kurita’s Center Force suffered even before they arrived near San Bernardino Strait. American submarines spotted their approach and reported it to fleet headquarters. They also attacked the force, sinking Kurita’s flagship and knocking out the cruiser Takao.

But Center Force pushed on, led by the Yamato. Shortly after sunrise on October 25, 1944, they found themselves off the Philippine Island of Samar amid the American amphibious support ships. The first to see them were aviators above the support ships, and soon Rear Adm. Clifton A. F. Sprague was calling loudly for help. His small, light aircraft carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts were no match for Kurita’s super battleships, cruisers, and destroyers.

Admiral Sprague’s cries for help brought down a hurricane of American planes from his own carriers and those of two other supporting task forces. The Japanese found themselves with beautiful targets but discovered that they themselves had become targets, as well. Kurita soon believed that he had run into the main American fleet, not just a small support group.

“Ziggy” Sprague did nothing to dissuade him. Hiding in passing rain squalls whenever he could, and sending his small escorts to fight super battleships, he managed to save much of his force until suddenly he heard cries of the Japanese retreating. Admiral Kurita overestimated the enemy force, didn’t realize (because of poor communications) that he was very close to accomplishing his mission, and was losing his ships at a rate he could not afford.

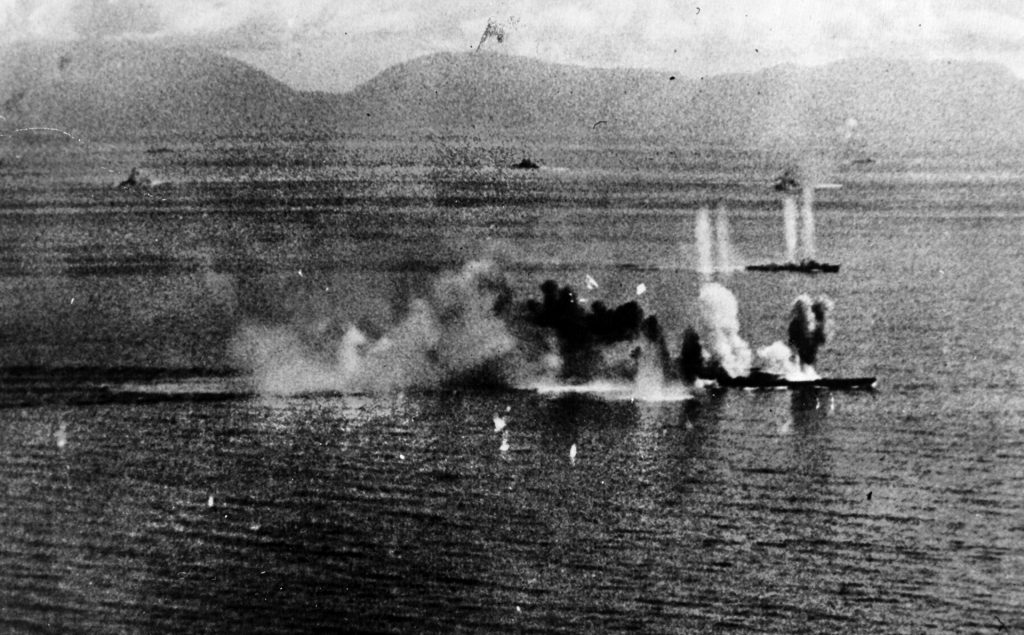

One of the main reasons for Admiral Kurita’s decision to withdraw was, no doubt, the fate of the Musashi. American aviators concentrated on her from the moment the Japanese appeared. She was hit by a bomb on Number One turret, which failed to explode. But a torpedo hit amidships, flooded the ship, and caused a five-degree list. Three more bombs and three torpedo hits on the port side caused another list, which was corrected by counterflooding.

But now the battleship was down six feet at the bow and taking additional bomb and torpedo hits. Soon the bow was down 13 feet and counterflooding would be counterproductive.

Moments later, the Musashi was slowing and had been left behind by the rest of the task force. More bombs and torpedoes hit home. A final attack hit her with at least 10 bombs and seven torpedoes. The ship’s list increased to 10 degrees to port, and the captain decided to run the ship aground to prevent her from sinking. But before he could, the ship’s engines stopped. Without power, the ship capsized and sank. Of her crew of 2,399, 1,376 survivors were rescued. American records indicate that she was hit by at least 19 torpedoes and 17 bombs, plus 18 near misses.

Meanwhile her sister ship, Yamato, suffered little. She fired her huge main guns for the first time in the war at the American carriers, but constant aerial torpedo attacks forced her to take evasive action, preventing continued firing. She took three bomb hits, of which only two struck near Turret Number One. The damage sent 3,000 tons of water rushing into the ship and created a five-degree list that was reduced by counterflooding. She kept up with the task force in its retreat, suffering additional bomb hits but no serious damage.

By November 23, 1944, IJN Yamato was back at Kure, undergoing repairs. She suffered a bomb hit from an American carrier raid on Japan while in port on March 19, 1945. Shortly after came word of the American invasion of Okinawa. The Yamato was about to make her last sortie.

It began between the Battle of the Philippine Sea and the invasion of Leyte in October 1944. With their air power in rapid decline and their navy nearly powerless to confront the oncoming Americans, the Japanese turned to desperation tactics. Although there had been individual suicide attacks by Japanese military men beginning with Pearl Harbor, these had been situations in which the soldier, sailor or airman had been badly wounded, or his plane too damaged to reach his base, and he had crashed into an enemy ship, base or other plane to take more of his enemies with him in his inevitable death.

But by October 1944, this tactic became official policy of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, known as the “Divine Wind,” or kamikaze. Begun on a mass scale in the Philippines, it had severely damaged American vessels and created a greater threat than any previous tactic.

When the Tenth U. S. Army (Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner) invaded Okinawa, it was clear that the next step would be the invasion of Japan itself. An all-out kamikaze strike began in early April and continued during the battle.

Anxious to participate, the Japanese surface fleet sought to make its own contribution to the great kamikaze effort. Of its three battleships remaining afloat, only the Yamato (Rear Admiral Kosaku Ariga) was in Japan and had enough fuel to reach Okinawa. Under the command of Vice Adm. Seiichi Ito, the Second Fleet, with the Yamato, light cruiser Yahagi (Captain Tameichi Hara) and eight destroyers, sailed from Ube, refueled at Tokuyama, and then sailed for Okinawa on April 6, 1945.

Unknown to the Japanese, the American submarine USS Threadfin had spotted their departure off the Bungo Suido entrance to the Inland Sea of Japan that same afternoon and reported their course and speed, identifying them as “two large and about six smaller ships.”

The plan, known as Operation Ten-Go, required the Second Fleet to sail to Okinawa, beach itself at the Hagushi roadstead on Okinawa in front of the advancing Americans, fire their guns until all ammunition was exhausted, and then join the ground fighting.

Led by the Yahagi and surrounded by the destroyers, the Yamato headed south to Okinawa; they were expected to arrive on April 9. That their mission was suicidal was made clear by the fact that they had only enough fuel to reach Okinawa, and none to return to Japan. The ships also had no air cover for this mission.

Once again, the task force had been sighted by American submarines, this time the USS Hackleback, and their course and speed confirmed to the senior American naval officer at Okinawa, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. The Americans had expected something of this sort, and Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Support Group (Task Force 58) was waiting for just such a move by the Japanese.

After receiving the two submarine contact reports, he ordered his four carrier task groups to move into launching positions northeast of Okinawa. One of the groups, Rear Adm. Ralph Eugene Davison’s Task Group Two (TG 58.2), was unavailable because it was refueling. Task Group 58.1 (Rear Adm. Joseph James (“Jocko”) Clark) and Task Group 58.3 (Rear Adm. Frederic Carl Sherman) launched search planes at daybreak on April 7. Search planes from the USS Essex (Capt. C. W. Wieber) quickly found the Yamato group southwest of Koshiki Retto. The Yamato was in the center of a circular group heading for Okinawa.

Admiral Spruance wanted to finish this last organized task group of the Imperial Japanese Navy. He ordered his Okinawa bombardment force under Rear Adm. Morton Lyndholm Deyo to go after the approaching Japanese ships. Admiral Deyo immediately formed a battle plan for his six battleships, seven cruisers, and 21 destroyers, keeping his ships between the Japanese and Okinawa. Although outgunned and out-ranged by the Yamato’s 18-inch guns, the Americans were more than willing to battle this threat to the Okinawa beachhead. But they would never get the chance.

Admiral Mitscher did not intend to stand by and watch another task group face the enemy force alone. As anxious as Admiral Spruance to finish off the Imperial Japanese Navy, he soon got his chance. Two amphibious patrol planes, flown by Lieutenant James R. Young and Lieutenant (j.g.) R. L Simms, left Kerama Retto and contacted the Japanese force. For over five hours they shadowed the Japanese, reporting on their position, course and speed. They also sent homing signals to Mitscher’s aircraft.

These reports gave Mitscher the opportunity he desired, and he launched his first strike aircraft shortly after 9:00 AM. Other strikes quickly followed. They arrived over the Yamato group shortly after noon on April 7. Ten minutes later, the first bombs struck the mainmast of the Yamato. Four minutes after that came the first torpedo hits.

For the second and last time, Yamato’s big guns opened fire on an enemy. But they had never been intended to strike at small, fast-moving targets, targets that were delivering tons of bombs and torpedoes at the Second Fleet. According to one survivor, the antiaircraft gunners were so inexperienced that they hit very few of the American planes attacking the battleship.

Five torpedoes slammed into Yamato’s port side, creating a flooding problem. Rear Adm. Ariga ordered counter-flooding of the starboard engine room and the boiler rooms. The flooding drowned the crews—several hundred men—in both locations. The Yamato now had only one working engine, and her speed diminished significantly.

Another wave of attackers arrived, and again torpedoes blew holes in her sides. Ten bombs were counted as hits on the deck above. The wireless room flooded, forcing the officers to communicate by flag and light signals.

One sailor recalled that the battleship was reduced “to a state of complete confusion…The desolate decks were reduced to shambles, with nothing but cracked and twisted steel plates remaining…big guns were inoperable because of the increasing list, and only a few machine guns were intact…One devastating blast in the emergency dispensary had killed all its occupants, including the medical officers and corpsmen.”

The final air assault came shortly after 2:00 PM that afternoon. The Americans now faced slowly moving targets with severely reduced firepower. During this last attack, a huge torpedo blast at the aft end of Yamato severed all communications from the bridge. The distress flag was hoisted.

With the steering room flooded and the rudder jammed hard left, the Yamato was now merely a target for its tormentors. The eyewitness remembered, “As though awaiting this moment the enemy came plunging through the clouds to deliver the coup de grâce…It was impossible to evade…I could hear the Captain vainly shouting, ‘Hold on, men! Hold on men!’…I heard the Executive Officer report to the Captain in a heartbroken voice, ‘Correction of list hopeless’ …Men were jumbled together in disorder on the deck, but a group of staff officers squirmed out of the pile and crawled over to the Commander-in-Chief for a final conference.”

By 2:40 PM. the Yamato was listing so severely that her battle flag was nearly touching the waves. Shells of the huge 18-inch guns rolled around dangerously on her decks, her guns no longer able to fire. Several shells exploded on the deck, adding to the carnage created by the American attacks. As she slid beneath the waves, a final “blast, rumble, and shock of compartments bursting from air pressure and exploding magazines already submerged” hurried her on her way.

One American flier saw the whole thing, although not as he would have wished. Lieutenant (j.g.) W. E. Delaney, a pilot from the USS Belleau Wood, had flown his Avenger bomber so low while dropping his bombs on the Yamato that he had been caught in his own bomb blast and forced into the sea. Both his crewmen had parachuted but would drown once in the ocean waters.

Lieutenant Delaney managed to get into his rubber survival raft, where he observed the death throes of the super battleship. Spotted by the scout pilots Lieutenants Young and Simms, he was rescued by Lieutenant Young in his unwieldy flying boat while Lieutenant Simms acted as a decoy to distract the Japanese from the rescue. Later, these two scout pilots would rescue several survivors of the Yamato.

Meanwhile, destroyer after destroyer was blasted below the sea, and next came the Yahagi’s turn. After the destroyer Hamakaze went down from a bomb hit, the naval aviators went after the Yahagi with at least a dozen bomb and seven torpedo hits. Captain Hara later recalled, “A lookout shouted, ‘Two planes on port bow!’ I looked up to see not two, but 20, 40, and more planes spilling out of the thick clouds. It was 1232 hours when I ordered, ‘Open fire.’”

Captain Hara was soon swimming with the rest of the survivors of his crew, watching the battle from a ringside seat. He watched as the first bombs struck the Yamato at 12:40 PM and the first torpedo a few minutes later. Ten more torpedoes followed, destroying the battleship’s trim. The Americans had learned from the fate of the Musashi to concentrate their attacks on one side of the great ship. Between 11 and 13 torpedoes hit the port side. Abandon ship was ordered.

Rear Adm. Ariga tied himself to the ship’s bridge binnacle to make sure he went down with the Yamato, and Rear Adm. Ito locked himself in his cabin. The ship rolled over to port and her aft magazines exploded, sending a plume of smoke visible in Kyushu, over 100 miles away. Only 269 officers and men survived the sinking of the world’s largest kamikaze. The Japanese lost 3,665, including 2,498 aboard the Yamato. The Americans lost 10 planes and 12 lives. The largest kamikaze was no more.