By Eric Niderost

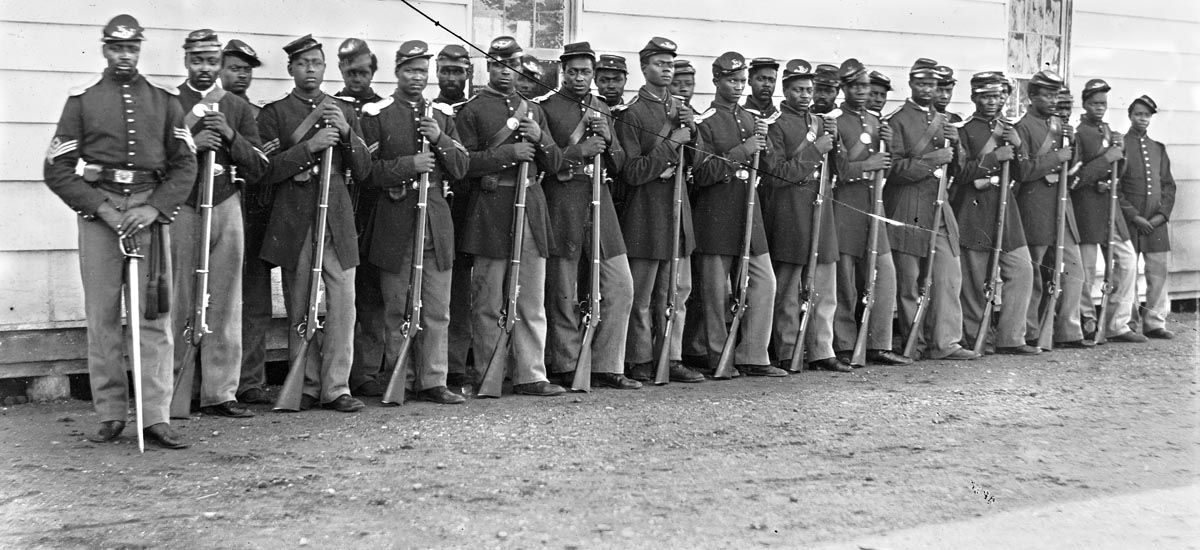

In 1864-1865 the U.S. Army had some 1,045,000 men in uniform; within a year after Appomattox, the number stood at 57,000. A penny-pinching Congress reduced the numbers further, until in 1874 its authorized strength stood at 25,000 officers and men.

The army was all volunteer, yet Congress did little to make a military career attractive. Pay was low; a private received $13 a month, a sergeant $21. Discipline was rigid, food poor, living conditions often abysmal. Yet recruits did come forward to enlist, and their reasons were as varied as the men themselves.

From Criminals to “Snowbirds”

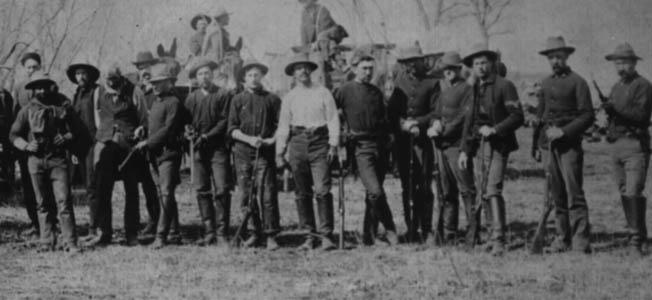

Some recruits were Civil War soldiers, men used to military life who had trouble readjusting to civilian ways. Others were wide-eyed country boys seeking adventure and escape from the drudgery of farm life—only to discover they had traded one form of hardship for another. Some were criminals seeking an anonymous refuge, others “snowbirds” intending to desert when spring brought better weather. There were even men who sought relief during economic depressions; hard times were the army’s best recruiter.

About half the men were foreign born. Between 1865 and 1874, 20 percent came from Ireland and 12 percent from Germany. The army was a source of steady employment and a chance to adapt to American culture.

Each cavalry or infantry regiment was composed of 12 companies. A soldier’s company was his whole world, and it was there that he formed the friendships—and acquired enemies—that would make his five-year hitch “heaven” or “hell.” A captain headed each company, but he was a remote, almost god-like figure. It was the First Sergeant who ran the company on a day-to-day basis, a man who was not afraid to enforce his authority with his fists if the occasion arose.

A Large Social Gulf and Hard Rations

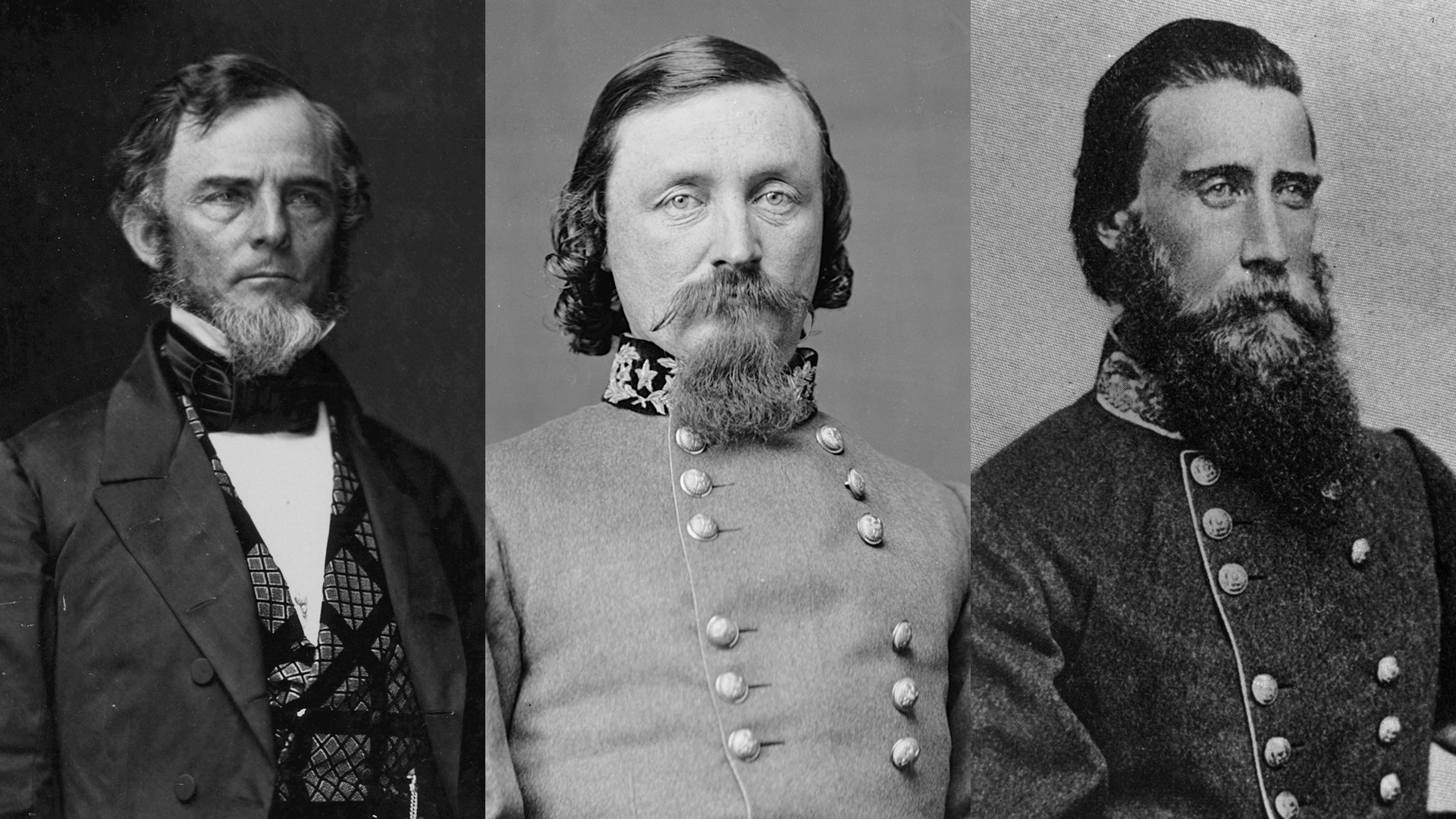

There was a large social gulf between officers and men, a chasm maintained by custom and regulations. Sometimes a man from the ranks would beat the odds and enter “shoulder strap society.” One example was Captain Myles Molan, a ranker who got a commission due to Custer’s patronage.

Although there were exceptions, most frontier forts were crude affairs, usually a few shacks centered around a forlorn parade ground. Soldiers slept on straw-filled mattresses, two to a bunk, and quarters were often infested with fleas and bedbugs. Indian fights were rare; full-scale campaigns like the Great Sioux War rarer still. Soldiers might spend months or even years without firing their guns, much less see an Indian. Their daily routine usually consisted of mind-numbing—and back-breaking—hard labor and drill. Rations would consist of hardtack, bacon, coffee, and salt pork, depending on circumstances. Wild game such as buffalo was welcomed, and some forts had vegetable gardens.

Not All Was Hardship

Not all were hardship posts; some of the larger establishments boasted such amenities as a bakery and comfortable—if spartan—barracks. Officer’s Row on a post might feature some very substantial homes; George Armstrong Custer’s quarters at Fort Abraham Lincoln were comfortable indeed.

Disease was a much greater threat to the average soldier than an Indian bullet. Accidents such as being thrown from your horse or accidentally shooting yourself took a toll. During Crook’s march a private from Captain Charles Meinhold’s Company B, 3rd Cavalry accidently shot himself with his revolver while chopping wood. The trooper later died of wounds.

Officers might be able to bring their wives to a fort, but enlisted men were largely deprived of feminine company. Larger forts had “suds row,” where laundresses and washerwomen cleaned clothes. Prostitutes could often be found plying their trade in “hog ranch” saloon/brothels, but most of these women were so unattractive and disease-ridden they were not likely prospects for mates.

Herculean Tasks Under Adverse Conditions

Ill-trained, ill-equipped, scorned by the public, and starved of funds by a stingy Congress, the U.S. Army of the 1870s operated under enormous handicaps. The real miracle was that it performed a herculean task so well under such adverse conditions.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments