By Mike Phifer

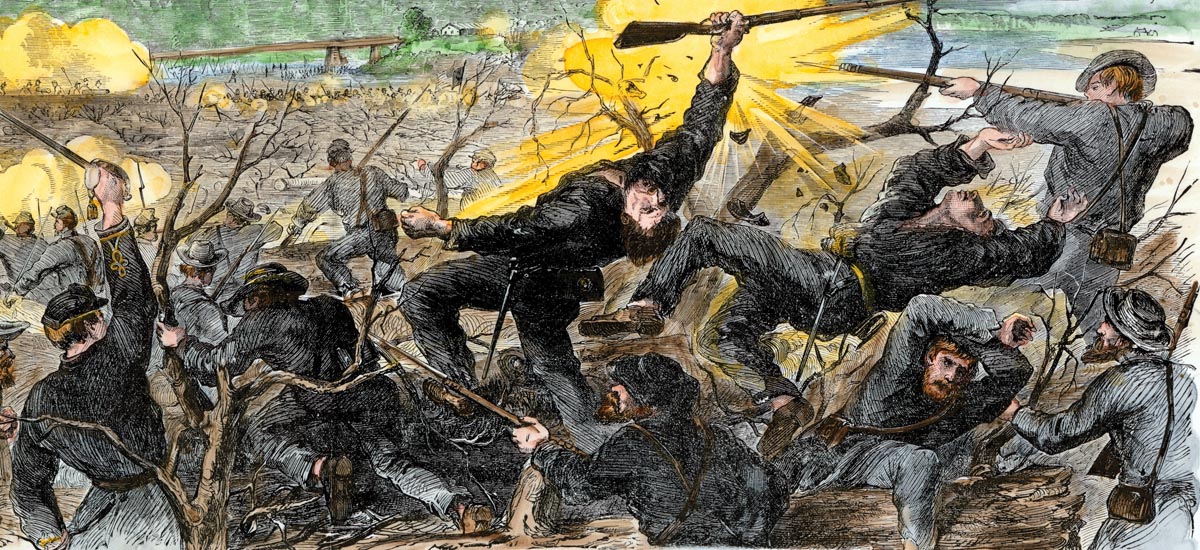

Confederate Brig. Gen. George Maney maintained tight control of the three regiments in his first line as he pressed his attack against a key position on the extreme left flank of the Union Army on the afternoon of October 8, 1862. The Battle of Perryville had begun less than an hour earlier, and Maney’s brigade was part of a sledgehammer attack by the reinforced Confederate right wing against Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s I Corps.

Maney’s immediate objective was to drive the Federals from an eminence known as Open Knob, one of the key positions on the north end of the battlefield. Situated atop the knob was Lieutenant Charles Parson’s eight-gun battery. It was supported by the 123rd Illinois of Brig. Gen. William Terrill’s brigade.

Maney’s Rebels, clad in faded gray uniforms that matched the flora so well that Federal staff officer Samuel Starling thought from a distance that they wore camouflage, had reached a split-rail fence overgrown with brush partway up the east slope of the knob. With his regiments suffering additional casualties from Federal fire with each passing minute, Maney gave the order to charge.

Reluctant to give up their position behind the fence, the men nevertheless heeded their veteran commander. The men might not have moved were it not for Maney’s exhortations. “His presence and manner … imparted fresh vigor and courage among the troops,” recalled Colonel George Potter, commander of the 6th Tennessee.

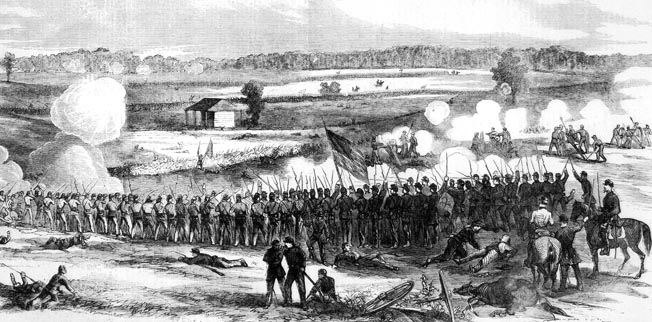

When the Rebels began their uphill assault, the Union gunners switched to double-canister. The spray of lead balls mowed down many of the Southerners. “It was almost impossible for mortal men to stand up in the face of such a rain of lead and our lines wavered a moment,” wrote a memberof the 41st Georgia. But the veteran soldiers recovered and swept uphill shrieking the hair-raising rebel yell. Color bearers fell to the ground wounded or dying, but always another soldier picked up the colors and bore them forward. In the 41st Georgia alone three color bearers were cut down by Yankee bullets or canister.

“The battery was playing upon us with terrible effect,” wrote Lt. Col. William Frierson of the 27th Tennessee. As a result of the artillery fire, “large boughs were torn from trees, the trees themselves shattered as if by lightning, and the ground plowed in deep furrows.”

Maney’s other two regiments caught up with the first line and joined the attack. In a desperate effort to save the valuable guns, Terrill ordered the men of the 105th Ohio, who had just reached the knob, to counterattack the Confederates. The Ohioans moved downhill and fired a volley. Most of the bullets passed over the heads of the Confederates.

In response, Maney’s men delivered a well-aimed volley that shattered the Buckeyes. The Rebels then chased them back to the top of the knob. What followed was a bloody scuffle for control of the guns. It was just one of the many desperate struggles that characterized the bloody fighting that afternoon.

At the outset of the American Civil War in April 1861, both sides coveted the key border state of Kentucky. “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly to lose the whole game,” said President Abraham Lincoln. The Bluegrass State was vital to the Federal strategy because it either bordered or contained within its borders four key waterways that the Union needed to move men and supplies. Its northern and western borders ran along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, respectively, and the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers flowed through the western part of state.

At the start of the war Kentucky attempted to remain neutral, although some of her sons served in the opposing armies. Kentucky’s frail neutrality was shattered in early September 1861 when Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, a former Episcopal bishop, ordered Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow to seize the key town of Columbus along the Mississippi River, believing the Federals were preparing to move into the state. The Federals subsequently occupied Paducah and Smithland. Union troops moved into northern Kentucky, and Confederate troops marched into southern Kentucky.

The Confederate Army’s hold on southern Kentucky was short lived. On January 19, 1862, Brig. Gen. George Thomas’s Union troops defeated Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer’s Confederates at Mill Springs. The following month, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant advanced into eastern Tennessee and captured Forts Henry and Donelson. Shortly thereafter, the Federals captured Nashville. The Confederates attempted to regain the initiative by striking Grant’s Army of the Tenneseee on April 6 at Pittsburgh Landing on the Tennessee River, but Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell arrived to reinforce Grant and on the second day of the battle the Yankees recaptured the ground they had lost. Since the Confederates retreated to Mississippi, the Battle of Shiloh was a Union victory.

Shortly afterward, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck left his headquarters in St. Louis to take command of the Federal forces in the field. By temporarily combining the armies of Grant and Buell, Halleck amassed an army of 125,000 men. He then advanced cautiously on Corinth, Mississippi.

Unlike Grant, Halleck was not a fighter. He allowed General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard’s 53,000-man Army of Mississippi to withdraw from Corinth on May 29 without having to fight a pitched battle. Halleck then dispersed his forces. Although some of the forces remained on the defensive, Halleck ordered Buell to capture Chattanooga, Tennessee.

A native Ohioan, Buell graduated from West Point in 1841. He served ably in both the Second Seminole War and the Mexican-American War, suffering a severe wound at Churubusco. Confederate partisans sought to sever Buell’s supply line that ran over the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The result was food shortages. Buell was reluctant to let his men forage, though, and instead put them on half rations. This made him unpopular with the troops.

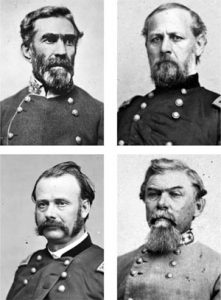

When Beauregard went on medical leave without clearing his absence from his army in advance with his superiors, Davis replaced him on May 6 with General Braxton Bragg. The new commander of the Army of Mississippi in Tupelo focused initially on obtaining adequate supplies and improving the army’s discipline before considering offensive action.

When Union Brig. Gen. George Morgan’s 7th Division of the Army of the Ohio occupied Cumberland Gap on June 18, thereby threatening Knoxville, Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Department of East Tennessee, fired off an urgent request for reinforcements to Bragg.

Smith, who graduated from West Point in 1845, was a veteran of the Mexican-American War as well as an Indian fighter who served in the 2nd Cavalry. The native Floridian had been shot in the neck while leading his brigade in spirited fighting on the Confederate left at First Manassas. Promoted to major general upon his recovery, Confederate authorities sent Smith to Knoxville to shore up its defenses. Although loath to reduce the size of his army, Bragg nevertheless sent Maj. Gen. John P. McCown’s 3,000-man division to Smith.

When Halleck divided his forces, Bragg seized the offensive. Leaving Maj. Gen. Sterling Price in command at Tupelo, Bragg embarked his 32,000 men by rail for Chattanooga. To get his army from Tupelo to Chattanooga by rail required taking a circuitous 776-mile route south to Mobile and then northeast via Montgomery and Atlanta to Chattanooga. The first group of Confederates entrained for Chattanooga on June 23.

Bragg and Smith met in Bragg’s hotel room in Chattanooga on July 31 to plan a campaign designed to expel Union forces from Tennessee. First, Smith was to take his 15,000 men and drive Morgan from East Tennesee. Then, Bragg and Smith would unite against Buell in Middle Tennessee. Should Grant reinforce Buell with Union forces in northern Mississippi, then Confederate forces in the Magnolia State under Price and Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn could retake western Tennessee.

Bragg, who was born in Warrenton, North Carolina, graduated from West Point in 1837. A veteran of the Second Seminole and Mexican-American Wars, he resigned from the U.S. Army in 1856 and became a sugar planter. His swift rise to the upper echelons of command had much to do with circumstance; namely, the untimely death of General Albert S. Johnston at Shiloh and the poor health of General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard.

The commander of the Army of Mississippi pinned his hopes in part on new recruits from Kentucky swelling his ranks. Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, who had begun raiding from East Tennesee into Kentucky in July, told Bragg that he should expand to receive upward of 25,000 additional men. Smith upended Bragg’s strategic plan almost immediately by setting his sights not on clearing the Yankees from Tennesee, but instead on invading Kentucky. Bragg agreed to participate in an invasion of Kentucky, but only after Smith had driven Morgan from East Tennesee.

On the night of August 13, Smith led his newly named Army of Kentucky north toward the state that bore its name. After detaching Brig. Gen. Carter Stevenson’s division to keep an eye on Morgan’s division at Cumberland Gap, Smith led his troops on a difficult march over treacherous mountain roads to Barboursville, Kentucky. In so doing, Smith cut Morgan’s supply line, which ultimately compelled the Union general to retreat to the Ohio River.

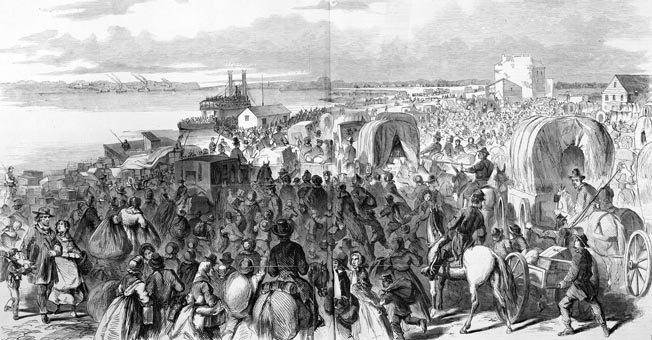

From Barboursville, Smith headed north toward Lexington, Kentucky. Greatly concerned over the Rebel invasion of the Bluegrass State, the Federals scraped together two green brigades to stop them. On August 30, Smith’s men soundly defeated the Yankees at Richmond. Smith’s begrimed soldiers marched into Lexington three days later to the gleeful shouts of citizens waving Confederate flags and cheering for Jefferson Davis.

Bragg, who had reorganized the Army of Mississippi into two wings each of which consisted of two divisions, led his army north from Chattanooga on August 28. As a result of the reorganization, Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk commanded the right wing and Maj. Gen. William Hardee commanded the left wing. The cavalry was divided into two brigades, one of which was under Brig. Gen. Joe Wheeler and the other under Colonel John Wharton.

When he received word that Bragg was on his way north, Buell marched to Nashville and then to Bowling Green, Kentucky. Bragg’s army stayed ahead of Buell. The vanguard of the Army of Mississippi reached Glasgow, Kentucky, on September 11. In order to cut Buell’s supply line, Maj. Gen. Jones Withers’ division occupied Cave City, Kentucky, thereby threatening Union trains on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.

The most vulnerable point on Buell’s supply line was Munfordville where 4,000 Federals at Fort Craig guarded the 1,800-foot-long bridge over the Green River. A force of 300 Confederate cavalry under Colonel John Scott reached Munfordville on September 13. Scott demanded that the Federals surrender, but their commander, Colonel John T. Wilder, flatly refused.

Believing Munfordville was lightly held, Scott requested assistance from Brig. Gen. James Chalmers at Cave City 12 miles to the south. Chalmers’ infantry marched to Munfordville to assist Scott. The following day Chalmers’ graybacks repeatedly stormed the fort but failed to capture it. When Bragg learned of the setback, he marched swiftly to Munfordville and besieged the fort. Outnumbered more than five to one, Wilder surrendered the garrison on September 17.

In the interim, Buell’s Army of the Ohio reached Bowling Green on September 14. From there Buell marched toward Bragg’s position at Munfordville, but Bragg had departed for Bardstown where he hoped to rendezvous with Smith.

With the road open to Louisville, Buell’s vanguard reached the city on September 25. Buell took the opportunity to rest his worn-out troops and assimilate reinforcements. Halleck was flabbergasted that Buell would dither while the Rebels were rampaging through central Kentucky. Although Halleck, with Lincoln’s approval, took steps to replace Buell with George Thomas, who had been promoted to major general on April 25, he rescinded the order when Thomas reported that Buell was ready to march against the Confederate forces in Kentucky.

Buell’s reinforced army numbered upward of 75,000 troops. The army was organized into three corps, each of which had three divisions. Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook commanded the I Corps, Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden commanded the II Corps, and Maj. Gen. Charles Gilbert commanded the III Corps. On October 1, Buell departed Louisville in search of the enemy.

Bragg, whose 30,000 troops were at Bardstown, urgently needed Smith’s 18,000 men to join him in order to give battle to Buell’s much larger Union army. But Smith remained at Lexington. Leaving Polk at Bardstown in command of the Army of Mississippi, Bragg rode to Lexington to assume overall command of the Confederate forces in Kentucky. While in Lexington, Bragg received a message from Polk on October 2 informing him that the Federals were on the move. Believing the Federals were headed for Frankfort, where he was planning the inauguration of the provisional Confederate governor of Kentucky, Bragg intended to hold the Yankees with Smith’s men while Polk struck them in the flank and rear.

Buell sent the divisions of Brigadiers Joshua Sill and Ebenezer Dumont towards Frankfort as a feint. As for the main army, its three corps marched east on separate roads. I Corps marched toward Taylorsville, II Corps toward Bardstown via Mt. Washington, and III Corps toward Bardstown via Shepherdsville.

Polk, who was at Bardstown, received reports that the Federals were converging on his position. He ordered his troops to withdraw east toward the Confederate supply base at Camp Breckinridge east of Harrodsburg. To do so, they would have to pass through the hamlet of Perryville.

After learning of Polk’s move, Bragg ordered the Armies of Kentucky and Mississippi to concentrate in front of Harrodsburg. Bragg then proceeded with the inauguration on October 4. The festivities were cut short when the Federals forced the Confederates to evacuate the Kentucky capital. By nightfall Frankfort was under Union control.

Smith decided not to join Bragg at Harrodsburg; instead, he bivouacked near Versailles. He informed Bragg that Lexington was threatened by Federal forces but stated that he was in a good position to cover it. Believing that a large Yankee force was threatening Smith, Bragg reversed course and ordered his army to move north from Harrodsburg and join the Smith’s army to strike a blow against Buell.

But reaching Harrodsburg was proving to be difficult for Maj. Gen. William Hardee’s troops for they were marching through unfamiliar country. As a result, they had no choice but to trail behind Polk’s men on the Springfield Pike. The Rebels soon came under attack by Yankee infantry belonging to Gilbert’s III Corps.

As Buell’s 55,000 men approached Perryville, McCook’s I Corps advanced cautiously along Mackville Pike, Gilbert’s III Corps advanced along Springfield Pike, and Crittenden’s II Corps advanced along Lebanon Pike.

Concerned over the fighting moving his way, Hardee fired off a message to Bragg. “Tomorrow morning early we may expect a fight,” warned Hardee. “If the enemy does not attack us, you ought to unless pressed in another direction send forward all the reinforcements necessary, take command in person, and wipe him out.”

After receiving Hardee’s message that the Federals facing him needed to be wiped out, Bragg ordered Polk to send Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s division to support Hardee. Polk arrived at Perryville late in the evening of October 7 and took command of the 17,000 Confederate troops assembled just north of the town. Bragg issued orders for Hardee and Polk to strike the pursuing Federals a hard blow. “Give the enemy battle immediately,” wrote Bragg. “Rout him, and then move to our support at Versailles.”

Believing that he faced the entire Confederate Army of Mississippi, Buell also intended to attack in the morning. As the three columns of Yankees neared Perryville, they not only watched for the enemy but also for water as a severe drought had dried up creeks and waterholes. By nightfall on October 7, III Corps was bivouacked about three miles west of the Confederates on the Springfield Pike.

Having spotted some pools of water in the otherwise dry bed of Doctor’s Creek, a tributary of the Chaplin River, a mile and half away, a group of Yankees slipped off into the night to try to fill their canteens. Unfortunately, they ran headlong into Confederates of the 7th Arkansas of Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell’s brigade. The Arkansas regiment was posted on Peter’s Hill overlooking the creek.

Under cover of darkness, a patrol from the 10th Indiana was sent forward to reconnoiter the Rebel position. Two companies of the 10th Indiana slid past Peters Hill. They ran headlong into Liddell’s men at Bottom Hill, a mile west of Perryville, and exchanged fire with them before falling back.

The next morning Gilbert ordered Colonel Dan McCook’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s division to take Peters Hill and secure the water at that location. They set out shortly after dawn to capture the objective. The rattle of musketry reverberated across the hills as McCook’s Yankees attempted to drive the Arkansans from Peters Hill. Both sides brought up artillery to bolster their infantry.

After an hour-long duel, Liddell counterattacked with the 5th and 7th Arkansas Regiments. When the Confederates were about 200 yards from Peters Hill, the Federal guns opened fire, tearing huge gaps in the gray battle line. The Rebels continued their advance and soon had to brave Federal musket fire at close range. Unable to stand the heavy fire, Liddell’s regiments withdrew into the relative safety of the woods in front of Peters Hill.

Gilbert ordered his 3rd Cavalry Brigade under Brig. Gen. Ebenezer Gay to clear the woods and valley of enemy soldiers in front of McCook. Gay reluctantly ordered his 2nd Michigan Cavalry, supported by the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, to advance dismounted against the Confederates in the woods. To assist Gilbert, Sheridan summoned Lt. Col. Bernard Laiboldt’s brigade and ordered its commander to move into position to support McCook.

The Rebel infantry laid down heavy fire. To make matters worse, Confederate artillery on Bottom Hill began shelling the exposed troopers. Despite their tenacious defense, the Federal troopers soon fell back among the trees that lined the dry bed of Bull Run Creek.

Sheridan then ordered Lt. Col. Bernard Laiboldt to commit two regiments from his brigade. Laiboldt sent the 2nd Missouri and the 44th Illinois into the fray with orders to push back the Rebels. With mounting pressure applied by Laiboldt’s troops and those of Brig. Gen. Speed Fry’s brigade, Liddell’s men requested permission to withdraw from Bottom Hill. Their request was granted.

At that point, Gilbert arrived on Peters Hill and noticed that Sheridan’s troops had captured Bottom Hill. He ordered Sheridan to recall his men to Peters Hill and remain on the defensive until a general advance was ordered.

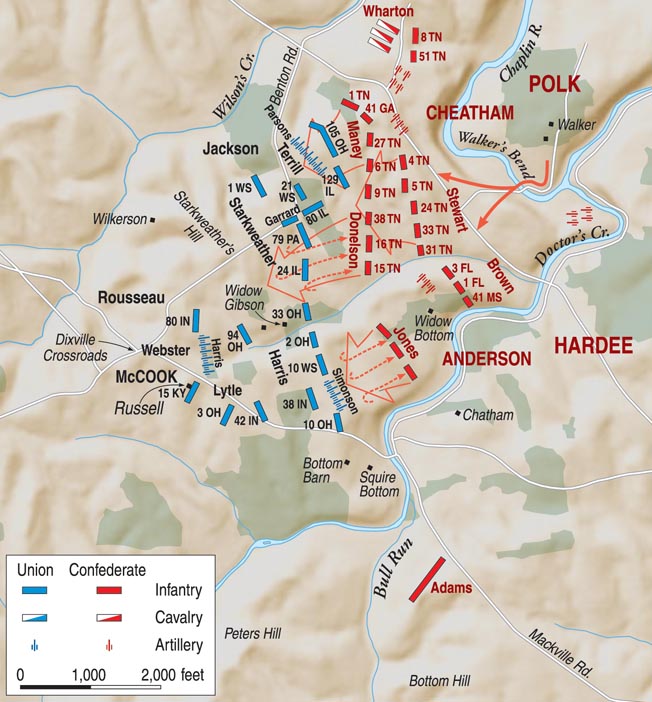

To the north, McCook’s I Corps deployed for battle. They were two hours behind schedule. Brig. Gen. James Jackson sent his two brigades to deploy on the left, while Brig. Gen. Lovell Rousseau put his three brigades into line on the right. By 1:30 pm all of McCook’s troops were on hand. The tardy arrival of his I and II Corps compelled Buell to postpone his attack until the following morning.

The Federals were not the only ones behind schedule. When Bragg arrived at midmorning, his mood turned sour when he learned that Polk had taken a defensive stance rather than an offensive one. Unaware that he faced the entire Army of the Ohio, Bragg considered it sufficient to leave two infantry brigades and Wheeler’s cavalry brigade to face the Federal II and III Corps, which were situated south of Doctor’s Creek. Bragg intended to use six brigades of Hardee’s left wing to supplement the main attack against McCook’s I Corps. He issued orders for the troops to attack en echelon at 1 pm. An en echelon attack, in this instance, consisted of having one brigade attack first, followed after an interval by a second, and so forth down the line until all brigades had been committed.

While Hardee’s wing crossed the Chaplin River, Cheatham’s 4,500-man division marched north to Walker’s Bend on the Chaplin River. The division comprised the brigades of George Maney, Preston Smith, Daniel Donelson, and A.P. Stewart. Although woods and hilly terrain kept the Confederate columns out of sight from the Federals, the Rebels’ kicked up a large dust cloud as they tramped along the dirt roads. Some of the Federals who spotted the dust clouds misinterpreted the movement for a Confederate retreat. They would soon learn otherwise.

Confederate guns began a preliminary bombardment at 12:30 pm. Federal guns soon responded. Reaching their assigned jump-off point at Walker’s Bend, Cheatham’s men prepared to attack. The native Tennessean assigned Brig. Gen. Donelson’s brigade to spearhead the attack. Stewart and Maney were to follow at 150-yard intervals.

But Polk received disturbing intelligence from Wharton. The astute cavalry commander had spotted a previously unseen column of Federal infantry marching along the Mackville Road to reinforce the Federal left. Polk feared that the new Federal column could turn his right flank. He preferred that it move into position before he launched his attack, and for that reason, he temporarily postponed the attack.

When the Confederate guns ceased fire, Bragg waited in vain for Cheatham’s attack. Disgruntled by the delay, he rode over to investigate. Polk explained the situation, and Bragg concurred with his decision.

Donelson’s men moved into position atop the bluffs at Walker’s Bend at 2 pm. The 15th and 16th Tennessee Regiments swept forward toward Captain Samuel Harris’s 19th Indiana Battery Light Artillery and Colonel George Webster’s brigade. The Tennesseans struggled to keep their lines intact as they moved over the rugged terrain.

Colonel John Savage’s 16th Tennessee pushed ahead of the rest of the brigade. The Federal guns opened great holes in their line. Instead of striking the left flank of McCook’s line of battle, the Tennesseans actually struck his center. As a result, they took fire from three directions.

Brigadier General William R. Terrill’s brigade anchored the extreme Federal left. Moving up behind it on the Benton Road at the time of the Confederate attack was Colonel John Starkweather’s brigade. Colonel George Webster’s brigade was recessed in the middle at Widow Gibson’s House. To Webster’s right, the brigades of Colonel Leonard Harris and Colonel William Lytle were formed into line of battle north of Doctor’s Creek with Lytle’s brigade astride the Mackville Road. Donelson thus received fire from elements of the brigades of Terrill, Webster, and Harris.

The 15th Tennessee shifted to the left of Savage’s regiment. The Tennesseans were screaming the Rebel yell as they made for a gap in the Federal line near the Widow Gibson’s Farm. The Rebels took possession of the outbuildings and exchanged fire with the Yankees to their front. The Federals plugged the gap. The weight of the Federal numbers became too much for Donelson’s Brigade. After enduring a terrible fire for 30 minutes, Donelson’s men fell back to their starting point.

Cheatham then ordered Maney to assist Donelson. Maney arguably was the best brigadier general in Bragg’s army, having served in both the eastern and western theaters. He commanded 1,500 men organized into five regiments. The four Tennessee regiments were veterans of Shiloh, but the 41st Georgia was a green regiment.

Quickly forming up the 6th Tennessee, 9th Tennessee, and green 41st Georgia, Maney sent them over a wooded ridge toward Open Knob. His other two regiments, the 1st Tennesee and 27th Tennessee, which had not yet reached the starting point, would have to catch up with the lead regiments.

Colonel James Monroe’s inexperienced 123rd Illinois, which was posted atop Open Knob with Lieutenant Charles Parsons’ Independent Battery, opened fire on Maney’s men as they emerged from the wooded ridge 100 yards to the east. Maney’s Rebels charged through canister fire to reach the top of Open Knob. A close-quarters fight ensued for control of Parsons’ guns during which Union Brig. Gen. James S. Jackson was slain as he tried to rally the 123rd Illinois. Maney’s men drove the Federals from Open Knob and captured seven of Parsons’ eight guns.

To the left of Cheatham’s divisions, two brigades of Brig. Gen. James Patton Anderson’s division of Hardee’s left wing began their advance as part of the Confederate right wing’s attack. Colonel Thomas Jones’s brigade spearheaded the Confederate assault aimed at Harris’s brigade.

The Federal fire proved too deadly for the attacking Confederates. Jones’s Magnolia Staters retreated under the withering fire. Next up was Brig. Gen. John Brown’s mixed brigade of Floridians and Mississippians. They rushed to the farthest point that Jones’s men had reached at which time Brown ordered them to fire from the prone position on the Federals. Both sides blazed away at each other, inflicting heavy casualties.

Major General Simon Buckner, who commanded Hardee’s 3rd Division, had four brigades led by Brigadiers Patrick Cleburne, Bushrod Johnson, St. John Liddell, and Sterling Wood. Buckner assigned Johnson’s Tennesseans to spearhead the attack. Just before Johnson set off with his men, Buckner ordered him to oblique to the left to give his men more cover from the terrain. But not all of Johnson’s regiments received the revised orders. The result was that there were major gaps between the regiments during the brigade’s attack. To make matters worse, they came under friendly artillery fire.

With matters straightened out, Johnson’s Tennesseans crossed the dry bed of Doctor’s Creek. They ran headlong into the startled Yankees of the 42nd Indiana who were scooping up water from the few remaining puddles in the empty creek bed. The Rebels pushed on for Colonel William Lytle’s brigade positioned to the right of Harris’s line on high ground near the home of Henry Bottom. The Confederates soon were hit by a vicious volley from the Federals.

The Tennesseans filed into position behind a stone wall near the Bottom House. The men hurriedly loaded their rifled muskets and began blazing away at the 3rd Ohio on high ground on the west bank of the creek. An artillery shell whistled through the air and slammed into Henry Bottom’s barn. Flames leaped skyward as the structure burst into flames. With only a few hours of daylight left, Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s brigade advanced to assist Johnson’s men, who were out of ammunition and pinned down behind a stone wall. The 3rd Ohio also was running low on ammunition. Colonel Curran Pope’s 15th Kentucky Infantry moved up to relieve the Ohioans.

Deployed to the left of Buckner’s division were the graybacks of Brig. Gen. Daniel Adams brigade of Anderson’s division. They struck the right flank of the 15th Kentucky, forcing part of the regiment, as well as the men of Colonel John Beatty’s 3rd Ohio, to face them. The Federals fixed bayonets in preparation for hand-to-hand combat.

Cleburne’s graybacks swept past the stone wall and up the hill, shells screaming down on them. The shells were not from Federal guns, but rather from their own guns. Some of Cleburne’s men were wearing captured blue pants from Union Army uniforms, and the Rebel gunners mistook the troops for Federals. Confederate officers soon put a stop to the errant shelling.

With the brigades of Cleburne and Adams advancing on his right flank and center, Lytle knew he could not check another Rebel attack. He therefore ordered the 3rd Ohio and 15th Kentucky to withdraw toward the Russell House, near Dixville Crossroads, where they could refill their cartridge boxes from the ammunition wagons there.

With Lytle falling back to his left, Harris also knew he would have to fall back as well. By this time Brown’s men had been resupplied with ammunition and resumed their attack. Brig. Gen. Sterling Wood’s brigade of Buckner’s division joined the action, while Donelson’s brigade and part of Brig. Gen. Alexander Stewart’s brigade joined the advance.

Cleburne’s main battle line continued its advance. Lytle was attempting to form another line when the Cleburne’s skirmishers popped over the ridge. The Yankees fired a volley in the mistaken belief that they were firing on Cleburne’s battle line. Before the bluecoats could reload, Cleburne’s brigade came up. It fired a volley at Lytle’s line and then charged against it. Lytle’s line broke under the pressure.

While trying to establish a rear guard, Lytle was wounded and captured. With the brigades of Lytle and Harris in full retreat, Hardee’s men pushed on toward Dixville Crossroads, the intersection of the Mackville and Benton Roads. If the Confederates could secure the crossroads, McCook would be cut off from the rest of Buell’s army.

At his headquarters two miles to the south, Buell was unaware of the danger facing McCook’s corps. Due to the hills surrounding his headquarters, Buell and his staff could neither hear the battle nor see it. It was not until 4 pm that a member of McCook’s staff arrived and informed the Union commander of the magnitude of the threat facing I Corps. The stunned commander immediately ordered Gilbert to send two brigades from his corps to assist McCook.

The situation on McCook’s left was grim. After taking Open Knob, Maney’s brigade continued its advance. Maney’s Rebels engaged Starkweather’s brigade, part of which was deployed on a hill near the Benton Road. The hill became known after the battle as Starkweather’s Hill.

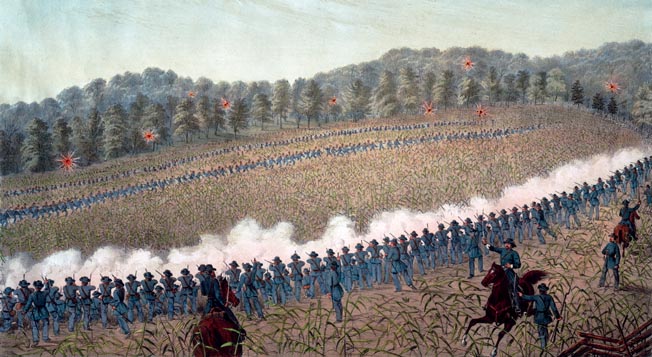

Having received two devastating volleys from the 21st Wisconsin situated in a cornfield in front of Starkweather’s Hill, Maney’s Rebels shattered the Wisconsinites’ cohesion and sent them fleeing for the rear. With the assistance of Stewart’s brigade, Maney’s Rebels continued their westward advance in an attempt to secure Starkweather’s Hill.

Two Federal batteries fired canister at close range into the ranks of the attackers. Despite the carnage the Rebels suffered, they pushed on to the crest of the hill. The Rebels sought to capture Battery A of the Kentucky Light Artillery. An intense hand-to-hand melee ensued in which the men of both sides wielded clubbed muskets and bayonets in a struggle for control of the guns.

A handful of the Wisconsinites ignored the hail of lead to help work four guns that were firing double canister at the attacking Rebels. The gunners were supported by bluecoats from the 1st Wisconsin and the 79th Pennsylvania of Starkweather’s brigade whose stinging volleys helped drive off the Confederates.

But the Confederates regrouped and launched a fresh assault. The Federal guns were “mangling and tearing men to pieces,” wrote Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee Infantry of Maney’s brigade. Another melee ensued for control of the 4th Battery of the Indiana Artillery. A Rebel battery began shelling Starkweather’s position, killing and wounding large numbers of his men. One of these was Terrill, who suffered a mortal wound.

Fearing that he could not repulse another attack, Starkweather withdrew 300 yards to the west where his brigade took up a new position atop a steep ridge. Starkweather knew he had to stop the Rebel advance, for Dixville Crossroads was only a half mile behind his second position.

The Confederates renewed their attack on Starkweather’s Hill in a fresh attempt to capture the Federal guns. Having lost the battery horses to enemy fire, Federal artillerymen and infantrymen dragged six guns and caissons to the new position. Other Federal units rushed to assist Starkweather’s hard-pressed troops. The Federal infantry now stood six deep behind a stone wall. The Federals’ heavy musketry punished the worn-out Confederates.

Cheatham’s attack was spent by 4:30 pm. His graybacks lacked the strength and numbers to make a third assault. McCook’s left flank had bent, but it had not broken.

With the sun dipping low in the sky, sporadic fighting continued on McCook’s right as Hardee’s troops tried their best to reach Dixville Crossroads. The Federals withdrew to Russell House, which was McCook’s headquarters, and established a new line from which to make a last stand. To encourage the men, Rousseau walked up and down the line of battle waving his cap back and forth atop his sword in an effort to rally his exhausted troops.

Having received two wounds, Cleburne led his troops to within 75 yards of the beleaguered Yankees when enemy artillery shells began to explode around them. By that point, Cleburne’s Rebels had moved beyond the units on their flanks, thus exposing them to enfilading fire. For that reason, as well as the need for more ammunition, Cleburne halted his attack.

Wood’s Rebels continued their advance. In the process of assaulting Rousseau’s line, they ran headlong into the newly arrived brigade of Colonel Michael Gooding, which belonged to Brig. Gen. Robert Byington Mitchell’s division. Gilbert had sent Gooding into action with orders to assist McCook. Vicious fighting raged as the Federals sought to shatter Wood’s brigade. Lt. Col. Squire Isham Keith’s 22nd Indiana repulsed the Rebels.

Hardee fed Liddell’s brigade into the fight in a last-ditch effort to break the Federal lines. Tramping over the rolling terrain in the growing darkness, Liddell’s men exchanged fire with the 22nd Indiana as the Hoosiers repositioned themselves to the left of Gooding’s brigade. Lt. Col. Keith believed that his men were trading fire in the gloaming with another Federal regiment. He shouted to his men that they were firing on friends and ordered them to stop.

Polk spurred his horse forward in order to determine the identity of the troops in his immediate front. He was shocked to learn it was the 22nd Indiana. When Keith asked Polk who he was, Polk tried to bluff his way out of the predicament. “I’ll soon show you who I am sir, cease firing, sir, at once,” he said. After riding along the enemy’s battle line, Polk rode to Liddell’s position. “General, every mother’s son of them are Yankees!” he shouted. “Open fire!”

Liddell’s graybacks poured hot lead into the Yankees. Three volleys felled two-thirds of the Hoosiers. Gooding, who rode up just in time to witness the carnage, was soon captured as the survivors of the 22nd Indiana fled the field.

With victory seemingly within reach, Liddell wanted to pursue the beaten Yankees. To his left, Liddell heard the enemy soldiers cheering as Brig. Gen. James Steedman’s brigade arrived on the field. The arrival of fresh Yankees broke Polk’s will to continue fighting. “I want no more fighting tonight,” he told Liddell.

The fighting on the southern sector was on a much smaller scale than that of the northern sector. Brig. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s division had repulsed an attack by Colonel Samuel Powell’s brigade of Anderson’s division. When Powell’s brigade withdrew, Colonel William P. Carlin’s brigade pursued Powell’s graybacks to Perryville and secured the west side the town.

Both sides claimed victory. The Confederates suffered 3,173 casualties, while the Federals suffered 3,805. Yet Bragg sustained proportionally the heavier casualties (20 percent compared to 7.7 percent) of the total force engaged. By the time the fighting ended, Bragg became aware that he had faced Buell’s entire army.

With the Federals poised to cut off Bragg’s escape route south, the Confederate commander issued orders for an immediate retreat. As for Buell, he failed to vigorously pursue Bragg’s army. For that reason, Halleck replaced him with Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans on October 24. The change in command occurred the same day that the dejected Confederates marched through Cumberland Gap into Tennesee. Kentucky remained firmly within the Union.