By Robert L. Durham

The men of Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson’s North Carolina brigade, four regiments strong, marched forward as if on parade, their rifles at the right shoulder, as they went into battle on the first day at Gettysburg. Their commanding officer stayed in the rear, so they were on their own. The field had not been reconnoitered, and no skirmishers had been deployed to their front.

They were marching toward the enemy but could see no sign of the Yankees except for some skirmishers, who quickly vacated their position. From behind a rock wall 80 yards in front of them, a brigade of Union soldiers suddenly rose up and fired a crashing volley. The Confederates had unwittingly walked into a trap. The Union musketry decimated the brigade’s left three regiments.

Due to the surface configuration of the field, the right regiment was left largely untouched. But the survivors of the other three Tarheel regiments went to ground in a depression that gave them scant protection. The Yankees continued to pour fire on them as they hugged the ground. The pinned-down Rebels eventually began waving their shoes and hats on bayonets to signal their desire to surrender. After the Union soldiers rounded up the prisoners, the dead lay behind in a straight line in grim testimony to the failed assault.

The episode occurred on July 1, 1863, the first of three days of fighting at Gettysburg. The Tarheels of Iverson’s brigade, which was a part of Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ division, had advanced into the devastating ambush owing to a number of factors, including poor leadership, faulty reconnaissance, and an absence of skirmishers to forewarn the main body of threats.

While Iverson bears the brunt of the blame for the destruction of his brigade, Rodes also shares in a portion of it. He was born March 29, 1829, in Lynchburg, Virginia. At 16 he entered the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) and graduated three years later. He rose to the rank of lieutenant and graduated 10th in a class of 24. Upon graduation, Rodes became an assistant at VMI. After his tenure, he came to be a railroad engineer, building railroads in Texas, Alabama, North Carolina, and Missouri. In 1856 he accepted a job offer from an Alabama railroad where he eventually rose to chief engineer. At the outbreak of the war in April 1861, he raised a volunteer company in his adopted state that became part of the 5th Alabama Infantry. He had the good fortune on May 11 to receive a commission as the regiment’s colonel.

The regiment was sent to Virginia in time for the Battle of First Manassas, July 21, 1861. The Alabamians served in Brig. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s brigade and were deployed on the army’s unengaged right flank where they saw no action. In the aftermath of the battle, promotions were coming fast and furious, and when Ewell was promoted to division command, Rodes received a promotion to brigadier on October 21.

The popular brigadier cut an impressive figure on the battlefield. Standing six feet tall, with a lean frame and gleaming eyes, he would prove every bit the warrior in his baptism of fire at Seven Pines on May 31, 1862. Rodes’ men impressively charged the Union lines three times that day, helping spearhead the attack of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s right wing. The first charge was part of the general assault to clear Casey’s Redoubt, the second charge occurred against a reformed Yankee line 150 yards in the rear of the redoubt, and the third charge was made against Yankees who had withdrawn into a tract of woods. In the third charge, his exhausted men suffered heavy losses.

Late in the battle Rodes rode toward the front with Brig. Gen. James Kemper, who had arrived with reinforcements, to show the Virginia brigadier where to insert his regiments. As he did so, a bullet struck his lower right arm. He stoically remained in command until the battle was over, at which time he relinquished command to Colonel John Gordon of the 6th Alabama.

“Rodes’ men were badly cut up,” wrote Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill, his division commander, in his battle report. It was evident not only to Hill but also to Longstreet that 33-year-old Rodes was a competent and effective leader. Hill later informed Richmond that Rodes was “a capital brigadier.” Rodes’ performance at Seven Pines was “distinguished for his coolness, ability, and determination,” Longstreet stated in his report. Rodes, who was in danger of having his wound become infected, stayed out of action for three months afterward.

During Rodes’ absence, his brigade was reorganized in accordance with Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s desire that regiments should be brigaded by state. To his existing 5th, 6th, and 12th Alabama Regiments, Rodes received two veteran regiments, Colonel Cullen Battle’s 3rd Alabama and Colonel Edward O’Neal’s 26th Alabama.

Rodes returned to his brigade and joined in General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland in September 1862. When the Union army began advancing rapidly toward South Mountain, Lee ordered Harvey Hill to take his division to the top of the ridge and block Turner’s Gap where the National Pike crossed the mountain. On September 14, Hill placed Rodes’ Alabamians on the division’s extreme left.

It proved a challenging assignment. Rodes’ 1,200 troops had to defend a 1,000-yard-wide front of rough terrain. As the battle for the mountain unfolded, none of Rodes’ regiments had contact with each other during the scrap that unfolded with veteran soldiers of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s I Corps. Rodes had to adjust his line several times. The Alabamians held their part of the line marvelously during a spirited four-hour clash but suffered 422 killed, wounded, and missing.

Three days later Hill deployed Rodes’ brigade in the Sunken Lane at Antietam where it played a key role in defending the Confederate center against a determined attack by Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner’s II Corps. As the Union attack reached a crescendo, Rodes turned away briefly to assist a wounded aide from the field. A misunderstood order resulted in the entire brigade withdrawing while Rodes was attention was diverted. He struggled to rally his men and eventually shook them into a new line along the Hagerstown Road.

Following the clash at Antietam, Harvey Hill received a transfer to Richmond where he took command of forces in that sector. Lee then made Rodes acting commander of Harvey Hill’s division, which was assigned to Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s II Corps. Rodes was present in command of the division at Fredericksburg, but it played no part in the battle. In March 1863, all of the brigade commanders in the division signed a petition to President Jefferson Davis calling for Rodes’ promotion to major general, as befitted a division commander. At the time, though, nothing came of it.

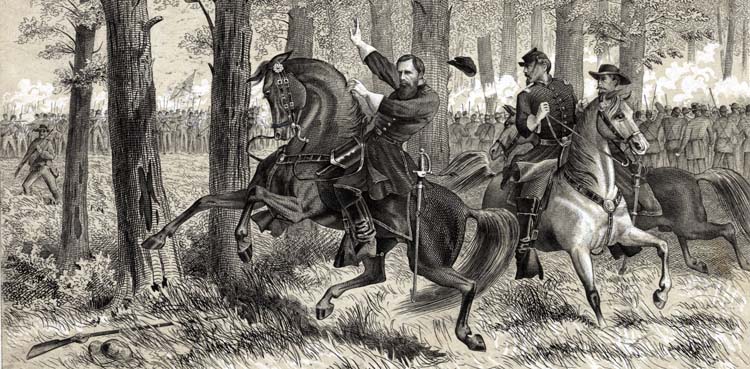

Rodes’ 7,800 men would play a prominent role in the Battle of Chancellorsville that spring. The division formed the first line of Jackson’s corps as it overran the Union army’s right flank on May 2. “Push ahead from the beginning,” Jackson told Rodes minutes before the attack. To ensure the attack would not stall out, “Old Blue Light” told Rodes’ brigade commanders that there was to be no stopping; if necessary, they could call on those brigades in the second line for support. “Forward men, over friend or foe!” shouted Rodes as his troops swept forward.

Rodes met every expectation that day. The victory was bittersweet for the South, though, as Jackson received a grave wound that required the amputation of his arm. In discussions with his surgeon, Dr. Hunter McGuire, and on his deathbed, Jackson praised Rodes for his performance in the recent battle. When Rodes visited Jackson a few days after his wounding, the general had a chance to praise Rodes in person. Lee personally wrote to President Davis on May 4 requesting Rodes’ promotion and recommending his assignment to permanent command of Harvey Hill’s division. The promotion, which was confirmed on May 7, was dated May 2 in order to acknowledge when the actions in battle occurred that merited his promotion.

Jackson’s leadership had been crucial to the Confederate success at Chancellorsville, and his absence at Gettysburg was very much apparent in the indecisiveness of the Confederate senior leadership. Following Jackson’s death, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia into three corps, and Rodes’ division became part of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps. At the time, it was the largest division in the army and had five brigades.

When Confederate III Corps commander Lt. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill became heavily engaged with the Union I Corps along the Cashtown Pike on the morning of July 1, Ewell directed Rodes to march south along the Carlisle Road to the sounds of battle. Ewell accompanied the division as it marched at double-quick time.

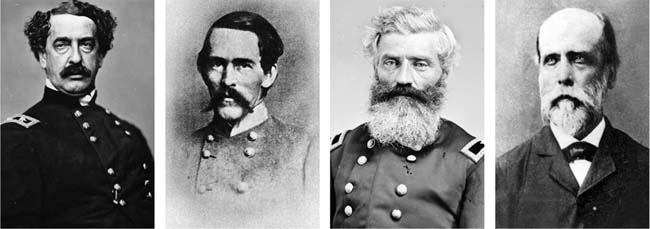

Rodes’ division had considerable leadership problems at the brigade level. Although brigadiers Stephen Dodson Ramseur and George Doles, who commanded North Carolinians and Georgians, respectively, were competent, the other three were either entirely untested or noticeably lacking in ability.

As for Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel, a West Point graduate, Gettysburg would be his first battle with the Army of Northern Virginia. His large brigade had been stationed during the first half of the war near Drewry’s Bluff on the James River and also on North Carolina coast. In the case of Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson, he did not have the confidence of his troops. Perhaps the most troubling brigade commander was Colonel O’Neal. A lawyer from Alabama, he commanded Rodes’ old brigade. Although Lee had thought O’Neal fit for brigade command, Rodes had serious reservations about his abilities.

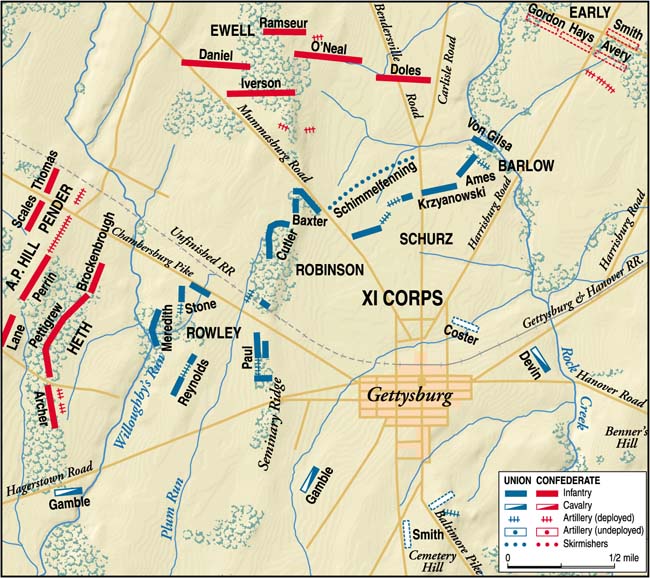

As the division approached the battlefield, Rodes deployed Doles’ brigade on the left, O’Neal’s brigade in the center, and Iverson’s brigade on the right. Daniel’s and Ramseur’s brigades deployed in reserve behind the others. At that point, Daniel was behind Iverson and Ramseur was trailing O’Neal. Rodes was wary of the threat the Union XI Corps posed to his east. Doles initially took up a defensive position to protect the division’s left flank. Rodes instructed him to tie into the flank of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division of the II Corps when it arrived on the field.

The division turned west off the Carlisle Road and arrived atop Oak Hill at about 1 pm. Although the division initially was in an ideal position to strike the Federal right flank, it would take Rodes 75 minutes to arrange his brigades for battle. Major Eugene Blackford led a battalion of sharpshooters, made up of the four best shots in each company of Iverson’s brigade. He deployed them forward, in front of Doles’ brigade around the Hagy farm, near the Mummasburg Road.

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Carter’s artillery battalion was attached to the division as its organic artillery support. Rodes ordered Carter to fire on the Yankees. Two of Carter’s batteries began to bang away at targets to their south, while the two remaining batteries faced southeast to shell Colonel George von Amsberg’s brigade of the Union XI Corps. In this location, four companies of skirmishers from the 45th New York had already deployed to screen the rest of the regiment.

Although Rodes may have hoped to fall on the Union right flank in a surprise attack, Colonel Thomas Devin’s cavalry brigade detected the arrival of Rodes’ division and warned Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday. Doubleday had succeeded to command of the Union I Corps following the death Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, who was slain at 10:15 am in the confused fighting in Herbst’s Woods.

Brigadier General Lysander Cutler’s brigade of the First Division of the Union I Corps occupied Shead’s Woods. As Doubleday realized the extent of the threat, he reinforced the right flank of his line. The I Corps commander dispatched Brig. Gen. Henry Baxter’s brigade of Brig. Gen. John Robinson’s Second Division of the I Corps to reinforce Cutler’s brigade. Baxter, a Michigan storekeeper before the war, moved into position on Cutler’s right atop Oak Ridge.

Just east of Oak Ridge, Colonel George von Amsberg’s brigade of the Third Division of the Union XI Corps deployed fronting north against Blackford’s sharpshooter battalion. While the Union reinforcements were moving into position, Rodes planned his attack in painstaking detail. He wanted to ensure his brigades were perfectly aligned before ordering an advance. By 2:15 pm he was ready to begin his assault.

Rodes final disposition for called for a two-brigade attack. O’Neal advanced on the left and Iverson on the right. Daniel’s brigade took up a position to attack en echelon on the right. Rodes instructed Daniel to either support Iverson directly or attack on his right. Ramseur’s brigade, which was situated behind O’Neal, would serve as a readily available reserve.

“I determined to attack with my center and right, holding at bay still another force, then emerging from the town,” Rodes wrote in his battle report. A defect in Rodes’ deployment was that he entrusted his opening attack to O’Neal and Iverson, who were his least reliable brigade commanders.

Iverson received instructions to coordinate his assault with that of O’Neal to his left. Likewise, Daniel was to coordinate his assault with Iverson. O’Neal’s regiments from left to right were the 5th Alabama, 6th Alabama, 26th Alabama, 12th Alabama, and 3rd Alabama. Rodes subsequently detached the 5th Alabama to cover the ground between the four attacking brigades and Doles’ brigade on the far left of the division. Rodes gave explicit orders to Colonel Battle to tie his 3rd Alabama Regiment into Daniel’s brigade. The division commander did this because he did not trust Iverson to execute the task.

As events unfolded, O’Neal’s brigade attacked with just three of his regiments. Instead of having 1,700 men in five regiments for his attack, he would have only1,000 men. O’Neal would later blame Rodes for having taken his two flank regiments away from him. Yet Rodes contended that he had informed O’Neal of this before his brigade advanced. To make matters worse, O’Neal did not advance with his brigade; instead, he waited behind with the 5th Alabama. This was contrary to standard practice, for all brigadier generals in the Army of Northern Virginia were required to personally direct their brigades in battle. This was essential to ensure that a brigade stayed on course and reacted quickly and effectively to changing circumstances.

O’Neal failed to inform Iverson that he was beginning his attack. His men headed directly south toward Baxter’s position. Baxter’s brigade, which was composed of six regiments, was deployed in a salient. The 12th Massachusetts was at the apex of the salient; its left companies faced west and its right companies faced north. Captain Herbert Dilger’s six Napoleon 12-pounders of Maj. Thomas Osborne’s Artillery Brigade of the XI Corps fired canister into the ranks of the 6th Alabama on O’Neal’s left flank.

Baxter ordered the 88th and 90th Pennsylvania Regiments to shift to the north to check the charge of O’Neal’s Alabamians. Since part of the 12th Massachusetts and the 83rd New York already were facing north, this gave Baxter sufficient strength to check O’Neal’s assault.

“The boys from the other side were coming right along,” said Private John Vautier of Company I of the 88th Pennsylvania. “Cocked and primed for a fight.” The Rebel skirmishers leading O’Neal’s brigade initially masked the three regiments behind them. When the brigade came to within easy range of the Federals, it experienced severe musket fire. “[Minie] balls were falling thick and fast around us, and whizzing past and striking someone near,” recalled Captain Robert Park of the 12th Alabama on the brigade’s right flank. Park received a wound that knocked him to the ground. “It was a wonder, a miracle that I was not afterward shot a half dozen times.”

As Rodes watched them, he saw that they were moving quickly but not in the correct direction. O’Neal’s ranks were in confusion and his attack stalled. Rodes rushed to the 5th Alabama and ordered Colonel Josephus Hall to lead his men forward to assist the rest of the brigade. “To my surprise, I found that Colonel O’Neal, instead of personally superintending the movements of his brigade, had chosen to remain with his reserve regiment,” Rodes noted in his report. “The result was that the whole brigade … was repulsed quickly.” After the battle, O’Neal would make the dubious assertion that when Rodes ordered the attack to begin neither O’Neal nor his staff could reach their horses in time to accompany their brigade.

With no time to waste, Rodes ordered Hall to deploy his regiment to the left of the 6th Alabama. The regiment moved rapidly forward past Moses McLean’s farmhouse at the foot of Oak Hill. To address the threat posed by the 45th New York’s skirmishers, Hall refused his left flank. Although the 5th Alabama came to within 50 yards of the Federal line, it was compelled to fall back since it was receiving front and enfilading fire with no hope of reinforcement. O’Neal’s charge had disintegrated after just 15 minutes. One of the key reasons for its failure was that O’Neal had failed to extend his line far enough to the east to take Baxter’s brigade in the flank and rear. In its disjointed attack, the brigade had suffered heavy losses. The survivors regrouped 300 yards to the rear.

Iverson found that O’Neal’s brigade had stepped off before he had a chance to coordinate his brigade’s movement with it. Iverson neither placed skirmishers in front of his brigade nor did he reconnoiter the ground over which his brigade would advance. As the brigade began its advance, the 5th North Carolina, 20th North Carolina, 23rd North Carolina, and 12th North Carolina Regiments were ordered left to right.

Baxter realigned his brigade so that all of his regiments were facing west. The regiments on his right flank were concealed behind a rock wall and had laid down their flags. Thus, Iverson’s advancing Tarheels simply saw a grassy field ahead and beyond it what appeared to be an unoccupied rock wall.

The North Carolinians were “sweeping on in magnificent order, with perfect alignment, guns at right shoulder and colors to the front,” Iverson wrote in his report.

Colonel Roy Stone’s brigade of the Third Division of the Union I Corps, which was deployed on McPherson’s farm, opened a destructive fire at long range on Iverson’s right flank. Lieutenant James Stewart, who commanded the 4th U.S. Artillery, Battery B, also opened fire from the Chambersburg Pike with three guns against the same target. Stewart’s battery was part of Colonel Charles Wainwright’s artillery brigade, which was the I Corps’ artillery support.

When Iverson’s men got to within 80 yards of Baxter’s position, the Yankees stood up and fired on the Tarheels. “At the command a sheet of flame and smoke burst from the wall with the simultaneous crash of the rifles, flaring full in the faces of the advancing troops, the ground being quickly covered with their killed and wounded as the balls hissed and cut through the exposed line,” recalled Private John Vautier of the 88th Pennsylvania.

“There seems to have been utter ignorance of the force crouching behind the stone wall,” wrote Captain Vines E. Turner of the 23rd North Carolina. “When we were in point blank range the dense line of the enemy rose from its protected lair and poured into us a withering fire from the front and both flanks.”

The survivors of Baxter’s initial catastrophic volley withdrew a short distance to a depression in the ground where they found themselves trapped. To stand up in order to advance or retreat in the face of such withering fire meant certain death. “The smoke was so dense that you could not perceive an object 10 feet from you,” wrote Captain Lewis Hicks of the 20th North Carolina. He said that the Confederates in the gully could not make up their minds “whether to lie still or to yield or to die fighting.” All the while, Baxter’s exultant Yankees continued to fire on them from the safety of the rock wall.

Both O’Neal and Rodes went forward to try to rescue the remnants of the shattered brigade. Yet before they could arrange for their rescue, the distraught troops in the depression surrendered. Some of Baxter’s men advanced from their protected positions to scoop up Rebel prisoners and send them to the rear; in the process, Baxter’s men captured the flags of the 5th, 20th, and 23rd North Carolina.

After the prisoners were gone, the line of dead killed in the opening volley shocked those who witnessed it. The blood from the dead bodies “ran like a branch,” recalled Turner. “And that, too, on the hot, parched ground.” Iverson, who was culpable in the slaughter, had the audacity to later state that he exonerated the survivors who had surrendered. Despite this, Rodes acknowledged that Iverson’s men had done their duty. “[Iverson’s] men fought and died like heroes,” wrote Rodes.

After the fight, there were rumors that Iverson was drunk and spent the battle hiding behind a log. The North Carolinians of Iverson’s brigade never forgave him for sending them leaderless into battle. Lee never forgave Iverson either. The commander of the Army of Northern Virginia ultimately had Iverson transferred to Georgia.

The 3rd Alabama of O’Neal’s brigade was still unattached and without orders. Battle offered his brigade’s assistance to Daniel, who gladly accepted. The 3rd Alabama fell in on Daniel’s left flank as they moved out of Forney’s Woods.

When Iverson advanced, his bearing left to strike Oak Ridge in a frontal assault unmasked Daniel’s left wing. Concerned about this, Daniel rode forward to reconnoiter the ground over which his brigade would be attacking Union forces. He observed that he would not only need to engage the Baxter’s and Cutler’s forces on Oak Ridge, but also check the fire of Stone’s regiments along the Chambersburg Pike to prevent his troops from receiving a deadly enfilading fire from these units.

Daniel therefore decided to divide his 2,000-man brigade. He sent the 43rd and 53rd North Carolina Regiments, as well as the 3rd Alabama from O’Neal’s brigade, to the left against Oak Ridge. To contend with the threat to his brigade from the south, Daniel ordered the 2nd North Carolina Battalion, 32nd North Carolina, and 45th North Carolina Regiment to advance south against Stone’s line. The officer commanding the 32nd North Carolina, though, became confused and his regiment was largely ineffective. Similarly, Lt. Col. W.G. Lewis, commanding the 43rd North Carolina, initially kept his regiment in place near the Forney House along the Mummasburg Road and did not follow the 53rd North Carolina and 3rd Alabama in their assault against the Federal line.

The 2nd North Carolina Battalion moved south on the left with the 45th North Carolina Regiment on its right. Waiting to receive their attack on the Chambersburg Pike were the 143rd and 149th Pennsylvania Regiments of Stone’s “Bucktail Brigade.”

The Tarheels’ moving south against the Bucktail Brigade ran headlong into a severe fire when they stopped to dislodge Yankee skirmishers from their position behind a fence. Having driven off the skirmishers, Daniel’s men began climbing over the fence. Just at that moment, the Bucktails on the south side of the Chambersburg Pike opened up with a heavy fire. Daniel’s two regiments wavered and temporarily halted. By this time, the Tarheels’ front rank had reached the railroad cut. While seemingly providing protection against enemy fire, the railroad cut also could prove a deadly trap. Earlier that day elements of Brig. Gen. Joseph R. Davis’s brigade of the Confederate III Corps had become trapped in a different section of the railroad cut.

Lieutenant Stewart’s guns fired canister at the Rebels as they approached the railroad cut. Some of the Rebels jumped into to the cut to escape the effects of the canister. From their left Confederates in the cut were struck by other Union guns that swept the cut itself with enfilading canister fire. Sensing that their side held the advantage, Lt. Col. Walton Dwight, commanding the 149th Pennsylvania, ordered his Bucktails to advance to the railroad cut. His men surged across the Chambersburg Pike, and when they reached the cut lay down along its southern lip where they were concealed by the lay of the land.

As the rest of the Confederates were scaling the fence to approach the cut, Dwight ordered his men to fire on them. A couple of well-aimed, thunderous volleys so disheartened the North Carolinians that they were put to flight. They retreated north about a quarter of a mile before Daniel arrived amid bursting Union artillery shells to rally them. To the south, Dwight had to withdraw his regiment to the Chambersburg Pike when incoming Confederate artillery shells made the position too warm to hold.

Not all of the Rebels had withdrawn from their positions along the cut, though. Some of the soldiers from the 2nd North Carolina Battalion were engaged in a hot exchange of musketry with the 143rd Pennsylvania anchoring Stone’s right flank. They eventually withdrew.

“At the railroad cut, which had been partially concealed by the long grass growing around it, and which, in the consequence of the abruptness of its sides, was impassable, the advance was stopped,” Daniel wrote in his report. Daniel ordered the remainder of his troops at the railroad cut to withdraw 40 yards to a hill. From their new position, they maintained a brisk fire on the enemy.

Daniel eventually reestablished his right wing on the crest of a low hill north of the railroad cut. Although the 2nd North Carolina Battalion and the 45th North Carolina Regiment had failed to inflict serious damage on Stone’s regiments or dislodge them, they had fought gallantly. In so doing, they had successfully protected the right flank of the part of Daniel’s brigade that was attacking Cutler’s division at the western edge of Shead’s Woods.

Daniel’s left wing, consisting of the 3rd Alabama on the left and the 53rd North Carolina on the right, advanced against three brigades of the Union I Corps occupying Oak Ridge and Shead’s Woods. As they made their way toward their objective, their battle lines were torn asunder by a combination of artillery and long-range musketry from Cutler’s men deployed at the edge of Shead’s Woods. The 53rd North Carolina had made it to within 50 yards of the smoke-wrapped Union line when the 3rd Alabama stopped abruptly. Colonel William Owens halted the 53rd North Carolina’s advance and had it fall back far enough to maintain alignment with the Alabamians. What Owens did not know at the time was that Colonel Battle had stopped his regiment in an effort to try to align it with the right regiment of Ramseur’s brigade.

As Daniel’s attack stalled, Rodes committed his reserve brigade to the fight. Ramseur’s brigade advanced boldly against the Union I Corps’ right flank. While the other brigades were advancing to the attack, Ramseur’s four regiments positioned at the rear of the division arrived in position about 3 pm.

By the time Ramseur formed up his troops for an advance at 3:15 pm, O’Neal’s assault had failed, and Iverson’s attack was unraveling. Ramseur initially divided his command to deal with the dire situation facing the other brigades that had attacked before him.

Ramseur dispatched the 2nd and 4th North Carolina on his left wing to assist O’Neal’s beleaguered troops. Then, astride his dark gray horse, Ramseur accompanied his right wing, composed of the 14th and 30th North Carolina Regiments, to assist Iverson’s mauled brigade.

Captain James Crowder, who commanded the 3rd Alabama’s sharpshooters, suggested to Ramseur that rather than strike Oak Ridge head on, he shift to the left in an attempt to take the Union troops in the flank. This is what O’Neal was to have done, but his troops were not far enough east to achieve their objective of turning the flank of the Union I Corps.

By mid-afternoon the extreme right of the Union I Corps was no longer held by Baxter’s brigade. Baxter had shifted to his left, and his old position was occupied by the five regiments of Brig. Gen. Gabriel Paul’s brigade, also of the Second Division of the I Corps. Paul had received orders at 1 PM. from division commander Robinson to take Baxter’s position. His men had begun arriving at that location about 90 minutes later, just as many of Iverson’s troops were surrendering.

Ramseur heartily agreed. Through some adroit maneuvering, which included a wheel to the left after marching across O’Neal’s front, Ramseur was in position to attack. After a brisk march, his men were panting.

“Boys, do you see that stone wall over yonder?” Ramseur said to the men he was leading. “Well, I want you to drive the Yankees from behind it, and then you can rest.” While Ramseur was preparing to attack, Rodes located Ramseur’s two left wing regiments and ordered them to rejoin the rest of the brigade for its attack on Paul’s flank.

As Ramseur’s brigade advanced southward to the attack, the 14th North Carolina was on its left and the 30th North Carolina on its right. The 4th was behind the 14th, and the 2nd was behind the 30th. Ramseur’s men would have to cover 600 yards of ground to strike Paul’s brigade. Working to their advantage was the fact that during the first half of their advance they would be concealed from the Federals by the lay of the land.

When Ramseur’s men came to the fence, their weight collapsed it and they continued their rapid assault. When they reached the Mummasburg Road, the front rank stopped and fired a crashing volley before the entire battle line resumed its charge. The 30th North Carolina ran headlong into the 104th New York, while the 14th North Carolina advanced against the 13th Massachusetts. The frenzied fighting shifted back and forth across the Mummasburg Road.

Paul’s men were taking heavy fire from the front, rear, and right flank. The Yankees began retreating in companies and regiments east toward Gettysburg. Ramseur had achieved what three brigades before him had been unable to do. Ramseur’s brigade was “ordered forward, and was hurled by its commander with the skill and gallantry for which he is always conspicuous, and with irrestistable force, upon the enemy just where he had repulsed O’Neal and checked Iverson’s advance,” wrote Rodes in his report.

The enemy “made but feeble resistance to the front attack, but ran off the field in confusion, leaving his killed and wounded and between 800 or 900 prisoners in our hands,” wrote Ramseur. To their credit, Baxter’s troops did not succumb to panic. Instead they fought a slow retreat, stopping occasionally to make a brief stand in to drive back the pursuing Rebels as they made their way one and a half miles to Gettysburg.

A short distance to the east, Brig. Gen. Doles’ Georgia brigade was deployed three-quarters of a mile east of the main force of Rodes’ division where it guarded the division’s left flank against the Union IX Corps. Doles had performed superbly, handling his brigade with great skill, during the Battle of Chancellorsville while serving under Rodes, and he would do the same at Gettysburg.

While Ramseur was preparing his attack, Doles was working closely with Brig. Gen. John Gordon, who commanded a brigade in Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division of the II Corps, on plans to assail Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow’s division of the Union IX Corps. Barlow’s division held an exposed, unsupported position on Blocher’s Knoll north of the town. The Union division commander had seized the commanding ground in an effort to prevent Doles from taking it and using it as an artillery position.

Rodes accompanied Doles’ attack, focusing great attention on it. Their respective contributions to the successful attack that unfolded at mid-afternoon on July 1 reflected positively on both of them. Doles led off at 3 pm with a two-regiment front consisting of the 4th Georgia on the left and the 44th Georgia on the right. The 12th and 21st Georgia constituted the reserve. The two lead Georgia brigades smashed into the left wing of Barlow’s crescent-shaped front line. Some of the troops that Doles drove from the field were von Amsberg’s men.

The XI Corps “gave way, vanishing as mist, for it was a fearful slaughter, the golden wheat-fields, a few minutes before in beauty, now gone, and the ground covered with the dead and wounded in blue,” wrote Private Charles Grace of the 4th Georgia Regiment of Doles’ brigade. Doles was nearly killed when his horse stampeded Union lines. Rodes estimated that his troops captured 2,500 Union soldiers during the rout of the IX Corps.

That evening Rodes redeployed his troops in and around Gettysburg. He attempted to launch an assault against Cemetery Hill in tandem with Early’s division; however, by the time Rodes had his men in place, Early’s assault had failed. It is interesting to note that Rodes had assigned Ramseur the responsibility of leading the assault. Although it is not known for certain why he did this, he may have been ill at the time.

Rodes did not lead any other attacks on the second or third days of the battle. When Maj. Gen. Alleghany Johnson failed to capture Culp’s Hill on the evening of July 2, Lee ordered Rodes to try again on July 3. To assist Johnson, Lee ordered Rodes to furnish part of his division for the fresh attack. Rodes subsequently dispatched O’Neal’s and Daniel’s brigades, which formed a second wave against the entrenched Union XII Corps on the morning of July 3. The attack failed.

Rodes’ decision to send inexperienced brigade commanders to spearhead his attack against the Union I Corps on July 1 was a key mistake. Yet taken on the whole Rodes’ performance on the first day at Gettysburg was above average, particularly considering that both Ramseur’s and Doles’ brigades achieved superb results.

Rodes would continue to play a significant role in the Army of Northern Virginia throughout the Overland Campaign of spring 1864. When Lee established an independent command that summer under Early to march up the Shenandoah Valley and threaten Washington, Rodes became part of Old Jubilee’s Army of the Valley. The former railroad engineer lost his life in the Battle of Third Winchester in September 1864. As he watched his troops advance against the enemy, Rodes’ horse threatened to bolt. As he sought to bring it under control, he was fatally wounded. His death was widely mourned, for Rodes had made substantial contributions to the success of Southern arms in the Eastern Theater.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments