By Pat McTaggart

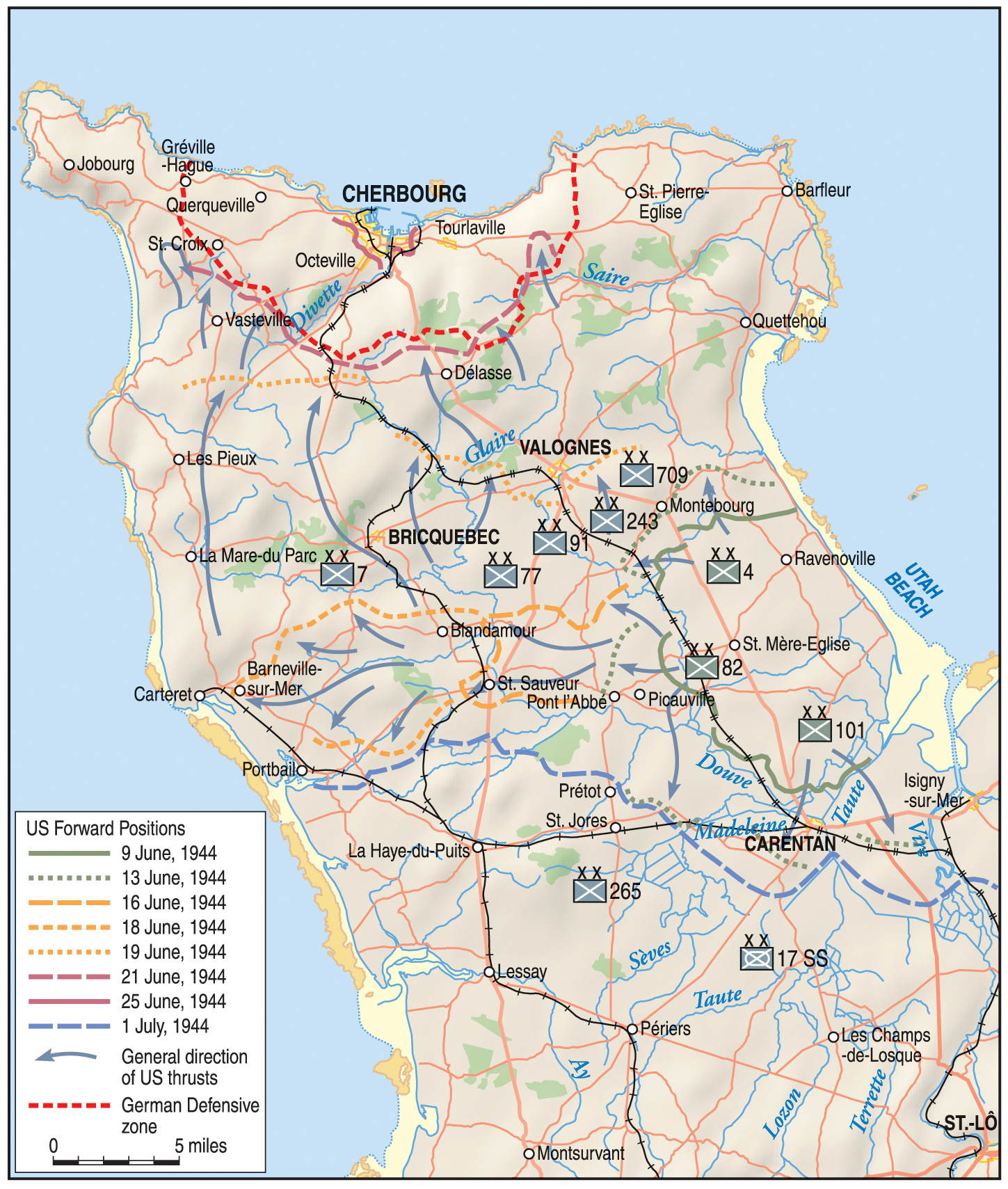

It was June 1944. Two generals, one American and one German, faced each other with diametrically opposed missions. The American, Maj. Gen. Joseph Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, commander of the U.S. VII Corps, had led his men ashore on Utah Beach on June 6.

Born in New Orleans in 1896, Collins attended West Point, graduating in 1917. After Pearl Harbor, he was sent to Hawaii to work on the islands’ defenses. In May 1942, he commanded the 25th Infantry Division on Guadalcanal and New Georgia. He was sent to the European Theater of Operations in February 1944 to take command of the VII Corps. After the breakout from the Normandy beachhead, his corps was charged with taking the Cotentin Peninsula and capturing the port of Cherbourg, which would give the Allies a desperately needed supply point on the European mainland.

Collins’ opponent was Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, who was born in Eisenach, Thuringia, in 1894. Von Schlieben entered the Kaiser’s army just before the outbreak of World War I and remained in service after the war in the 100,000-man Reichswehr. At the beginning of the Russo-German conflict, von Schlieben commanded an armored infantry regiment, rising to command the 18th PanzerDivision during the massive tank battle at Kursk in 1943. In December 1943, he took command of the Hessen-Thuringian 709th Infantry Division, which was garrisoned in Cherbourg.

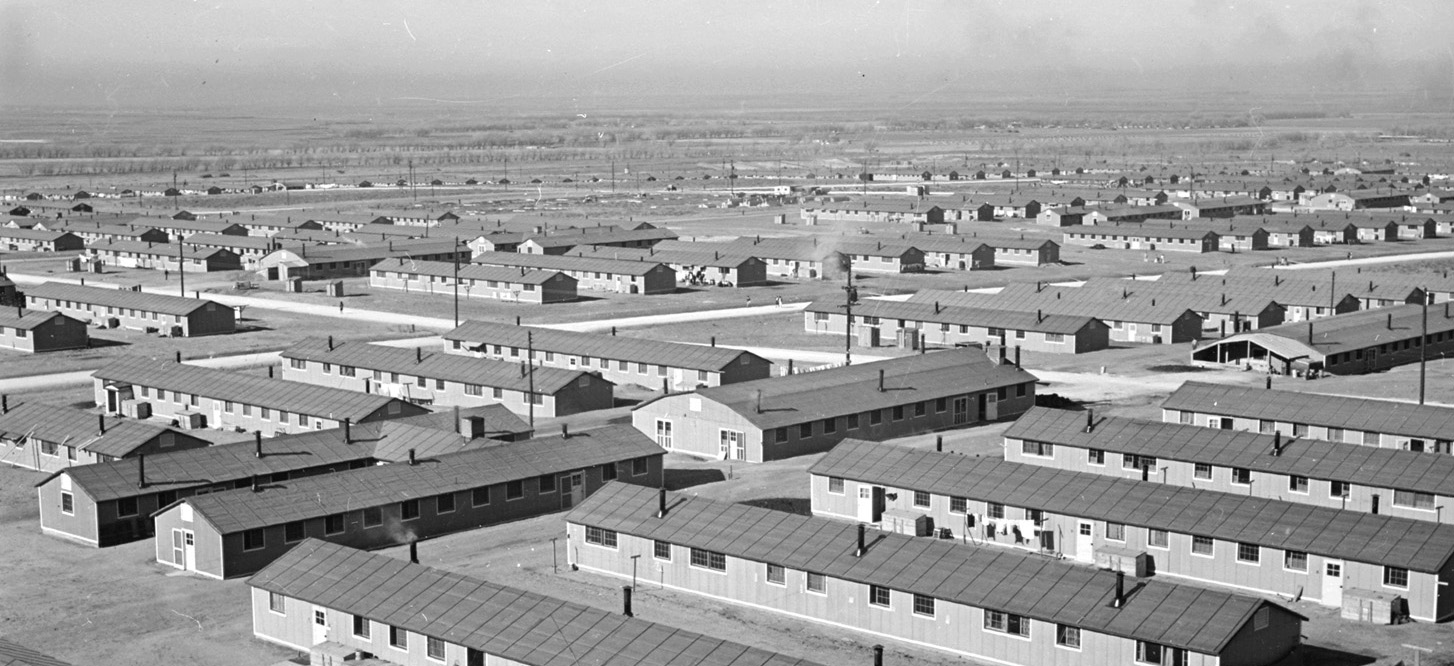

The 709th was a static division, formed with older men in April 1941. It had been on garrison duty in France since November of that year and was transferred to Cherbourg in November 1943. In 1944, the average age of a soldier in the 709th was 36 years. The division’s primary mission was to deny the port of Cherbourg to the enemy in case of invasion. Like other German divisions in Normandy, the 709th would be sorely tested in the next few weeks.

During the months before D-Day, von Schlieben kept his men busy patrolling the interior and guarding the beaches and roads of the Cotentin Peninsula. The duty was not particularly dangerous, and the population, while not overly friendly, was not overtly hostile. For the most part, the French inhabitants went about their daily tasks, doing their best to ignore the men in field gray that were stationed nearby.

Besides being the garrison for the 709th, Cherbourg was also the headquarters of Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Walter Hennecke, the naval commander of Normandy, which meant that the port was also filled with officers and men of the Kriegsmarine. In his position as naval commander, Henke had access to all the updated weather reports that would affect his ships. Looking at the latest data on June 5, he was fairly confident that the French coast would be safe from invasion, at least for the next few weeks.

The following morning, at about 0630, the first companies of Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton’s 4th Infantry Division began the assault on Utah Beach. During the night of June 6, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions had landed a few miles inland to prepare the way for the invasion forces.

Von Schlieben’s Infantry Regiment 919 was initially overwhelmed by the ferocity of the air and sea bombardment that hit the German strongpoints along the beach. Leutnant Arthur Jahnke, commander of one of the strongpoints, felt as if a giant fist had picked him up and slammed him against the wall as shells and bombs hammered his position. His experience was depicted in the movie The LongestDay.

Tubby Barton’s 4th Division sustained minimal casualties during the landing, most of them victims of mines. The airborne forces in the interior had done their job well, causing confusion among the Germans and preventing reinforcements from attacking the American infantry as the landings progressed. By the end of the day, Barton had consolidated his forces and was ready for his next mission, capturing Montebourg, the gateway to Cherbourg. The 55-year-old general had commanded the 4th since 1942, and he was certain that his men would have little problem in dealing with what he assumed were disorganized German defenders on the peninsula.

One of the keys to sealing off the Cotentin Peninsula was the capture of Carentan, which straddled the main highway running from Cherbourg to Paris, known as Route Nationale 13. It was also the main rail center for lines running from the peninsula to the mainland of France. The troopers of Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne Division were given the task of taking the town.

Unfortunately for Taylor’s men, General der Artillerie Erich Marcks, the brilliant one-legged commander of the LXXIV Army Corps, which was charged with defending the peninsula, was in possession of captured operational plans for Collins’ VII Corps. The plans had been found by members of a Russian battalion from the 352nd Infantry Division while inspecting a heavily damaged landing craft. Inside the briefcase of a dead beachmaster was the entire Allied scenario for the capture of the Cotentin Peninsula, including day-by-day objectives for the American V and VII Corps and the British XXX Corps.

After studying the documents, Marcks dispatched the Green Devils of Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant Colonel) Friedrich von der Heydte’s Fallschirmregiment 6 to defend Carentan. The stage was now set for a deadly confrontation between two paratroop units, von der Heydte’s Green Devils and the Screaming Eagles of Taylor’s 101st.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway’s 82nd Airborne was fighting to gain a bridgehead across the Merderet River for Collins to use as one of his jumping-off points for the assault on Cherbourg. Ridgway’s troopers had rough going against a tough and experienced regiment of the 91st Luftlande(Air Landing) Division. The German division was led by Oberst (Colonel)Eugen König, who took command after GeneralleutnantWilhelm Falley was killed on D-Day. The 82nd eventually established a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the river by June 8, only to be met with heavy German counterattacks.

A seesaw battle ensued, with the determined paratroopers gradually gaining the upper hand. Finally, the bridgehead was secured and the newly arrived 90th Infantry Division passed through the exhausted lines of the 82nd to keep the Germans on the run. Ridgway’s bloodied troopers breathed a collective sigh of relief as they watched the 90th, commanded by Brig. Gen. Jay W. McKelvie, march past.

The 90th was a green division, newly arrived in Normandy and untested in battle. As the division advanced through the hedgerows and farmland, the carnage from the 82nd’s battle unnerved many of the young soldiers. One of the leading units suddenly opened fire on what appeared to be a large group of Germans advancing toward the Americans, killing or wounding almost all of them. A few minutes later it was found that the Germans were prisoners from the previous fighting and were being led back to the beach by a handful of American guards. It was the first of several mistakes that would plague the 90th on the Cotentin Peninsula.

While the 90th struggled in the Merderet bridgehead, the battle for Carentan was still in full swing. By June 9, Taylor’s Screaming Eagles had bypassed the town and occupied the village of Saint-Côme-du-Mont, four miles north of Carentan. The main prize, however, had still not been attained.

Von der Heydte’s young paratroopers (many were teenagers) fought like tigers to hold Carentan. Expertly camouflaged positions among the hedgerows and causeways gave ample opportunity for the Germans to ambush the Americans trying to breach their lines. They also launched several counterattacks, one of which almost overran an American battalion headquarters.

The severity of the fighting caused horrendous casualties. In a forward dressing station just behind the German line, a pair of captured American doctors worked side by side with their Wehrmacht counterparts, operating on hundreds of Americans, Germans, Russian volunteers, and French civilians who had been wounded in the battle.

It was not until June 12 that the paratroopers and glidermen of the 101st finally took Carentan. The capture of the town united the American forces from Omaha and Utah Beaches, giving the U.S. troops a truly viable front. Almost one week after D-Day, the main supply route to the Cotentin Peninsula had finally been cut.

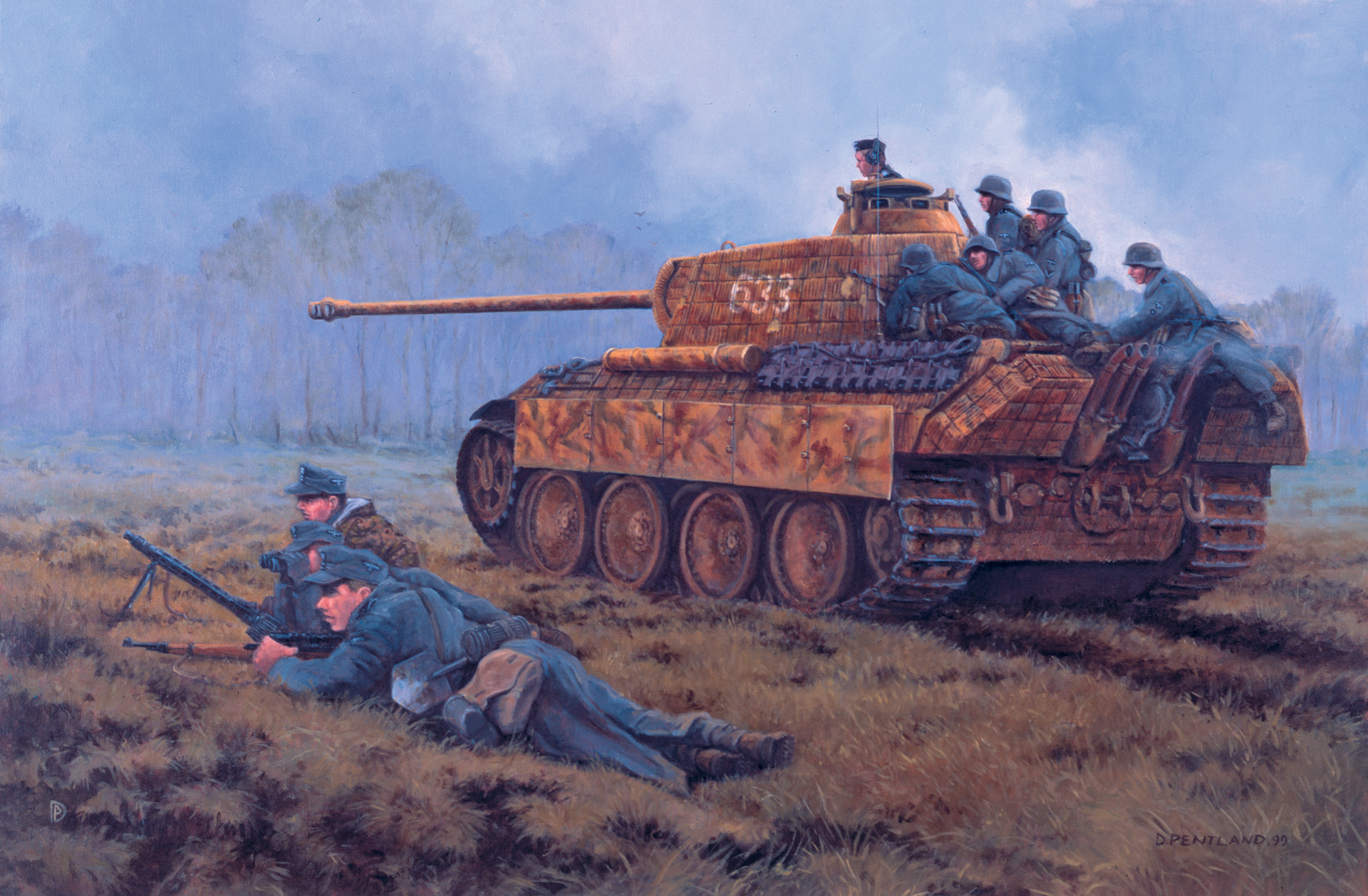

Von der Heydte and the remnants of his regiment were back in action a day later in a futile counterattack to retake Carentan with Brigadeführer (Brigadier General) Werner Ostendorff’s 17th SSPanzergrenadier Division. Before the attack, von der Heydte cautioned Ostendorff not to be overly optimistic. “Surely those Yanks can’t be tougher than the Russians,” Ostendorff scoffed.

Von der Heydte, who had been in the thick of many battles on the Russian Front, looked Ostendorff straight in the eyes. “Brigadeführer, not tougher but considerably better equipped, with a veritable steamroller of tanks and guns.”

Supremely confident, Ostendorff cut short the discussion. Supported by von der Heydte’s regiment, the SS division moved to the attack. They soon found themselves in a hornet’s nest, with American artillery cutting wide swathes through their ranks. In vain, Ostendorff urged his men forward.

By the end of the day, the SS general was forced to call off the attack to regroup his shattered division. Ostendorff now understood the meaning of von der Heydte’s words and realized that without adequate air and artillery support it would be futile to try another costly attack against the American positions.

At Cherbourg, von Schlieben had quickly sent several Kampfgruppen (battle groups) to the south as soon as he heard of the invasion. Together with elements of Generalleutnant Heinz Hellmich’s 243rd Infantry Division, which was also stationed on the peninsula, they formed a defensive line dotted with bunkers and strongpoints. These positions had been a problem for the 4th Infantry Division for several days.

Tubby Barton faced a formidable enemy line before he could attempt to take Montebourg, about 10 miles northwest of Utah Beach. The hedgerows in the area offered the Germans a natural defense that channeled attacking forces through preplotted avenues of fire. Von Schlieben’s men also had the advantage of occupying the high ground, where they could observe any attacking enemy coming at them over the relatively flat coastal terrain.

During their advance, the Americans had bypassed several German strongpoints, including Saint-Marcouf and Azeville. Oberleutnant Walter Ohmsen commanded the Marine Artillery Abteilung 260 (Naval Artillery Detachment) located in Saint-Marcouf. Supported by a mixed bag of infantry and a few assault guns, Ohmsen’s artillery caused heavy casualties among the follow-up American troops charged with taking the surrounded enemy positions. The two German strongpoints were also able to support each other with artillery fire until the Americans finally took Azeville on June 9.

Ohmsen held out for another two days. His combat strength was down to 18 officers and men, including several wounded who could not be moved. Surprisingly, the buried telephone cable connecting his battery with Hennecke’s headquarters in Cherbourg had not been broken by the incessant American shelling. On June 11, he received permission from the admiral to attempt a breakout.

That evening, those who could travel quietly slipped through the American lines, the seriously wounded being left behind with an NCO medic. The small group made it to the German lines after a harrowing night’s trek and continued on to Cherbourg. On June 14, Ohmsen was awarded the coveted Ritterkreuz (Knight’s Cross) for his actions at Saint-Marcouf. Like many officers that received the award, Ohmsen said that it was the men who served under him that made the award possible.

On June 8, the 4th Infantry Division and the 505th Paratroop Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne began an attack on the Quineville-Montebourg-Le Ham ridge, which had to be taken before Barton’s division could advance up the eastern coast of the peninsula. The position was held by an artillery group commanded by Major Friedrich Küppers, who had been personally chosen by von Schlieben to hold the ridge.

ONE OF KÜPPERS’ PRINCIPAL missions was to support elements of the 919th Infantry Regiment and the 243rd Infantry Division that were withdrawing from the Utah Beach area due to overwhelming Allied superiority. The Americans realized the importance of the German position and, after two days of intense air and naval bombardment, Küppers’ troops were mentally and physically near the end of their tether. Küppers tried to keep morale up, stressing the importance of holding the position, which was the key to Cherbourg.

When Barton began his advance against the withdrawing German units, his regiments ran into a maelstrom of hot steel. Küppers’ 19 guns ranged from the lethally accurate 88mm to larger 150mm howitzers and were supported by several flak guns and mortars, which only added to the carnage. The Germans had pre-targeted areas so that defensive positions in the hedgerows were protected by a wall of artillery fire, further slowing the Americans.

Barton’s 22nd Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Harvey Tribolet, advanced on the American right flank along the coast. To its left were Colonel Russell Reeder’s 12th Infantry Regiment and Colonel James Van Fleet’s 8th Infantry Regiment. The left flank of the advance was covered by Colonel William Ekman’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Despite the fierce pounding from Küppers’ artillery, the American forces gradually pushed the Germans back so that by June 12, Van Fleet’s unit was able to dig in along the Montebourg-Le Ham road.

Things were not going as well in McKelvie’s sector. Already spooked by their march to the front, the 90th all but folded in the face of the devastating German artillery fire. As air and ground bursts ripped through their ranks, the screams of the wounded and dying mingled with the roar of artillery explosions. With men falling all around them, the inexperienced troops tended to bunch up for protection, causing even more casualties from the German barrage.

On June 13, the day after Van Fleet’s men reached the Montebourg-Le Ham road, the 90th was still foundering in front of its own jump-off positions. Lightning Joe, always a man of action, visited the division’s sector and was appalled by the lack of leadership that seemed to plague the unit.

After his tour of the area, Collins contacted Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of the First Army, and reported the situation. He recommended that McKelvie be relieved and that a new commander, Maj. Gen. Eugene Landrum, take over the 90th immediately. The recommendation was approved, and the 90th was temporarily pulled out of the line so that Landrum could “clean house” and replace lackluster officers with men of his own choosing.

The poor performance of the 90th and the incredibly tough German defense had upset the timetable for the capture of Cherbourg, which was scheduled for no later than June 14. Despite the best efforts of most of the American units, the peninsula had still not been sealed off from the rest of France, and German supplies and reinforcements were still trickling into the Cotentin through gaps in the American lines.

To complete the job of severing the peninsula from the mainland, Collins called upon Ridgway’s battle-weary 82nd Airborne to finish the mission. The newly arrived 9th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy, would assist the airborne troops in achieving the objective. Eddy’s division was a tough, battle-tested unit that had seen combat in North Africa and Sicily. Its troops had no illusions about the enemy that faced them, and the men knew that they were in for a difficult time.

On June 15, Collins ordered the attack to commence. His timetable had already been upset, and Lightning Joe was in no mood to accept any more setbacks. Barneville, a small village overlooking the Atlantic Ocean on the eastern side of the peninsula, was the objective of the American attack.

Oberst König’s 91st Luftlande Division, which had been in constant action since the invasion, faced the two American divisions. The 91st was a mere shell of its former self, but König’s men still had some fight left in them, and they used the swampy terrain to their advantage. As the Americans advanced, they were hit with fire coming from the hedgerows and thick vegetation that covered the area.

Despite the enemy fire, the paratroopers of Colonel William Ekman’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment managed to make good progress. During their advance, the troopers took hundreds of prisoners, but most were found to be non-Germans who had volunteered or had been forced into joining the Wehr-macht. As the prisoners were marched toward the rear, the air was filled with conversations in Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Czech, and even Korean. For the most part, the captured troops looked relieved that their ordeal was over.

It was soon apparent to the men of the 9th and 82nd that their prisoners had been deliberately placed in the front line to serve as little more than an annoyance to the advancing troops. The Germans had never really expected that the foreign troops would fight very hard, but they did serve the purpose of slowing Collins’ advance. When the two divisions ran up against defenses manned by regular German troops of the 91st, it was a different story.

North of the 82nd’s avenue of attack, Eddy’s 60th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Frederick de Rohan) ran into a hornet’s nest when it hit the defenses manned by the battered but determined Germans. As de Rohan’s men sought to overcome the enemy positions, the Germans launched a counterattack that brought the surprised Americans to a halt. A stalemate continued for several hours until Colonel George Smythe’s 47th Infantry Regiment was thrown into the battle, forcing the Germans to retreat. By the end of the day, Eddy’s division had settled into positions west of Orglandes in the center of the peninsula.

New German forces had been brought into the line, principally Generalmajor Rudolf Stegmann’s 77th Infantry Division, which had come up from Brittany. Even with this influx of reinforcements, the superiority of Allied air and naval forces made the German defenses virtually untenable.

Throughout the evening of the 15th, sporadic firing broke the stillness of the front as the exhausted American and German troops tried to catch a few hours of rest. By daybreak, German NCOs were making their rounds, ensuring that their men were roused from sleep and ready to continue the battle.

“Get up boys,” a veteran Feldwebel (sergeant) said, “the Amis will soon be knocking at the door again.” As the men pulled themselves from their resting places, an ear-splitting roar pierced the relative calm of the dawn. “Get down,” the Feldwebel yelled, as shell after shell crashed into the German positions. On the 82nd Airborne’s front, artillerymen and mortar crews worked at a frantic pace, firing their weapons nonstop and raining havoc on the enemy line.

The barrage was followed by a massed attack of American fighter-bombers. The aircraft hit enemy positions around Saint-Saveur-le-Vicomte with such fury that the German defenders were forced to retreat even before the Americans launched their ground assault. Paratroopers advanced through the shattered town and were met with German artillery fire. Soon, Saint-Saveur-le-Vicomte was permanently in American hands.

North of the 82nd, Eddy’s 9th Infantry Division reached the Douve River. The general halted his division and sent the 47th Regiment south to a bridgehead that the 82nd had established on the far side of the river. The 60th Regiment regrouped around Saint-Colombe, about three miles north of the bridgehead.

The following day, Eddy’s regiments attacked. Heavy fighting again ensued as the 9th ran into remnants of König’s LuftlandeDivision. By evening, Colonel de Rohan’s 60th Infantry had reached Saint-Jacques-de-Nehou, about six miles from Barneville. The exhausted troops had hoped to spend the night in the village before resuming their march to the coast, but it was not to be.

In the waning hours of the day, an American armored car suddenly sped into the village. As the vehicle came to a halt, the troops were dumbfounded to see Lightning Joe himself emerge. After conferring with the lead battalion commander, Collins sent a message telling Eddy to meet with him immediately.

“I know that your boys are tired, “ the corps commander said when Eddy arrived, “but the Germans are in worse shape. I think that we can break them if we keep moving tonight.”

Details were hastily worked out, and Eddy set his two regiments into motion once again. Throughout the night, the Americans pushed steadily forward, gaining momentum as they went. In the early hours of June 18, advance patrols reported that they had reached the ocean. The Cotentin Peninsula was finally sealed off from the rest of France.

As the Americans worked to consolidate their position, Generalmajor Stegmann attempted to save his division by breaking out to the south. The general tried to lead his men out, but he soon fell victim to the dreaded American “Jabos” (the German slang for fighter-bombers) that swooped down on his staff car and riddled its occupants with 20mm shells. Only a day before, Generalleutnant Hellmich had been killed by American fighters. General ofArtilleryMarcks had suffered a similar fate on June 12.

Command of the 77th went to Oberst Rudolf Borcherer. The remnants of the division continued to move south throughout the day and into the evening. Early on June 19, Borcherer’s leading battalion ran into the 2nd Battalion of the 47th Infantry Regiment from Eddy’s 9th Division. The Germans launched an old-fashioned bayonet charge that netted more than 200 prisoners and opened the way for the survivors of the 77thto escape. Borcherer led the division, which was now below regimental strength, until September, when it was destroyed at Dinard.

The situation at Montebourg was now hopeless. Without the 77th, Major Küppers’ right flank was wide open, but his orders were firm. He was to hold his position for as long as possible. What Küppers did not know was that Colllins was ready to strike again with three divisions that were poised to shatter the German line.

Cherbourg’s capture became even more important on the 19th, when a Channel storm began to batter the man-made Mulberry harbors that were vital in funneling supplies to the Allied forces in France. To underscore the importance that Berlin attached to holding the port, Hitler, who rarely gave up any territory willingly, finally agreed to authorize a fighting withdrawal for the units south of the city.

Von Schlieben’s command was redesignated Kampfgruppe Cherbourg and included his own 709th Infantry Division and Grenadier Regiment922 from the 243rd Infantry Division as well as the various miscellaneous Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine units stationed in the city. With his new command, von Schlieben also received the following message: “You are hereby appointed the commander of Fortress Cherbourg. You will defend the city to the last man and the last bullet. [Signed] Adolf Hitler.”

The withdrawal consent seemed like a gift from heaven to Major Küppers. His battered Kampfgruppe was in danger of being flanked by the Americans, and there was little hope of holding out another day. After consulting with von Schlieben, Küppers ordered his men to retreat. Covered by overcast and drizzle from the Channel storm, the remnants of his Kampfgruppe made their way toward Cherbourg to occupy new positions guarding the port.

It did not take long for the Americans to figure out what was happening. As reports of the withdrawal reached Collins, the corps commander turned his divisions loose. The attack took place on a three-division front, with Eddy’s 9th on the left and Barton’s 4th on the right. The newly arrived 79th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ira T. “Billy” Wyche, would advance up the center.

It turned into a foot race, with the Germans having a few hours’ head start. American reconnaissance units pressed forward, warily checking out abandoned enemy defensive positions before moving north again. Behind them, the three American divisions found themselves slowed by natural obstacles more than German rear-guard actions.

Meanwhile, exhausted German units began arriving at the outer defensive areas of the port, with some battalions down to company strength when they finally reached their new positions. The survivors of the terrible Cotentin meat grinder were about to make their final stand.

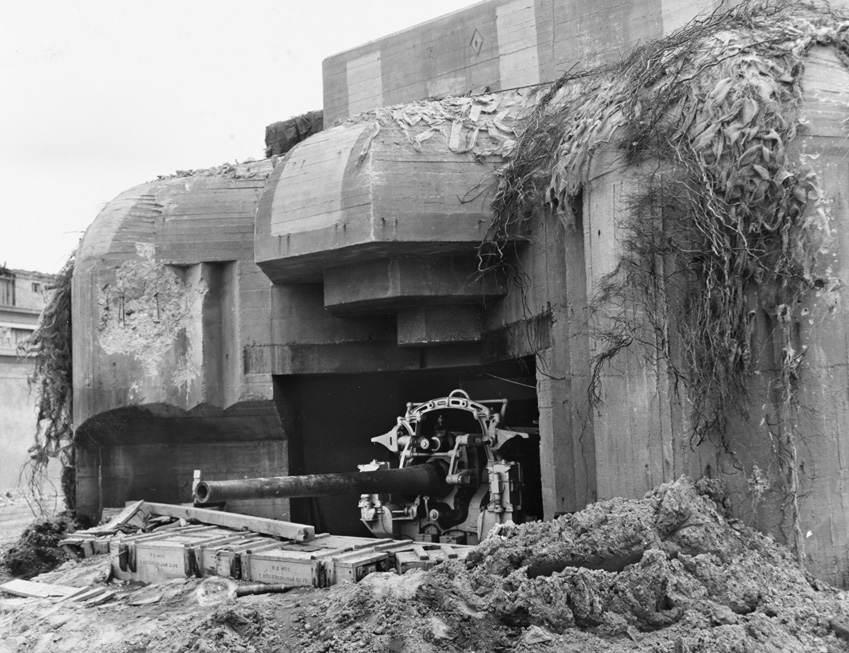

Cherbourg’s outer defenses were formidable. For the past four years, German engineer and construction battalions worked to strengthen old fortifications and build new ones in case the port was threatened. The outer line was a semicircle of forts, bunkers, and trenches four to six miles from the center of the city, with strongpoints dotting the high ground surrounding the port.

The Americans would have to approach through terrain covered by streams, hills, cliffs, and man-made ditches. Von Schlieben’s deadly 88mm dual-purpose guns were positioned to cover main avenues of attack.

The task of defending Cherbourg fell to four understrength Kampfgruppen.Kampfgruppe Müller (Oberstleutnant [Lt. Col.] Fritz Müller with Grenadier Regiment 922) was responsible for the peninsula west of the port. The center of the line was held by Kampfgruppe Keil (OberstleutnantGünther Kiel with Grenadier Regiment 919and Maschinegewehr [Motorized] Batallion 17) and Kampfgruppe Köhn (OberstWalter Köhn with Grenadier Regiment 739). Kampfgruppe Rohrbach (OberstHelmuth Rohrbach with GrenadierRegiment 729) held the east flank of Cherbourg.

A series of secondary positions had been constructed nearer the town, and the harbor itself contained a number of strongpoints and bunkers. Von Schlieben and Hennecke had their command posts in a huge underground bunker in the suburb of Octeville. The personnel inside the bunker were caught in a stifling underground world that had no air conditioning and little ventilation to clear the smells of men and battle.

Collins had a great deal of information concerning Cherbourg’s defenses, courtesy of the French Underground. As the Americans prepared to assault the port, junior officers could thoroughly study their objectives with maps of surprising detail and work out the best approaches with the least enemy covering fire.

Von Schlieben knew that his position was hopeless, but he hoped to gain time to complete the destruction of the harbor facilities. He also knew that he was tying down American forces that could be used to break out of the Normandy beachhead. His orders to his Kampfgruppen commanders were simple: “Dig in and hold.”

Supplies were another headache for the German general. He had already been forced to cut his men’s rations in half, and there was little hope of receiving any more supplies, especially with the Allied control of the sea and air. With American forces drawing closer, the general was forced to issue a proclamation resulting in dire consequences for any German soldier who shirked his duty. The June 21 order read: “Withdrawal from the present positions is punishable by death. I empower all leaders of every grade to shoot on sight anyone who leaves his post because of cowardice. The hour is serious. Only willpower, readiness for fighting and heroism to the death can help.”

Even this Draconian measure could not stop the American advance. Units of the 79th Infantry Division took a fort and several pillboxes in the outer defensive ring with the help of accurate air attacks. By the evening of the 21st, Collins’ three divisions were poised to begin a final assault on the port the following day.

The three-pronged attack was preceded by a massive air bombardment from hundreds of American and British fighters and bombers. At just past 1230 hours, the first wave of Allied aircraft appeared over the German lines. Swarms of fighter-bombers dove on the enemy fortifications, pummeling them with bombs and rockets. Then came the bombers. More than 600 medium aircraft came over in waves, blasting the German positions with thousands of tons of explosives. Other explosions were heard in the distance that day. Faced with the inevitability of eventual surrender, von Schlieben ordered the destruction of Cherbourg’s harbor facilities to commence.

Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Captain, equivalent to Lieutenant Colonel) Hermann Witt, the harbor commandant, was in charge of the demolition. In a letter to this author decades later, the naval officer said that his men were working day and night to place charges that would make the facilities inoperable for months. “Even so,” he wrote, “the process would take a few days to accomplish.”

Mines had also been placed in the harbor. Many of them could be exploded by remote control from a panel in Fort Westeck, which would make Allied entry into the harbor nearly impossible until the entire port had been captured.

As the bombers departed, more than a thousand artillery pieces opened up on the German line in a tremendous display of Allied materiel superiority. Following the barrage, Collins ordered his divisions forward. Billy Wyche’s 79th advanced from the south while Eddy’s 9th came from the west. Barton’s 4th took on the eastern sector. As assault units neared the German positions, the dazed survivors of the bombing went into action.

The 4th ran into a buzzsaw of fire as it hit the remnants of KampfgruppeRohrbach and gained only a few hundred yards before nightfall. Eddy’s 9th was stopped in front of Kampfgruppe Müller, and the 79th ground to a halt in the face of fierce resistance from KampfgruppenKeil and Köhn. As night cloaked the battlefield in darkness, German and American soldiers practically fell where they were, hoping to get a few hours of sleep before continuing the battle.

June 23 was another day of savage fighting. More air strikes hit the Germans, destroying several strongpoints and opening the way for penetration into the defensive belt. The 9th Division was able to destroy several bunkers and push Kampfgruppe Müller across a key ridge leading to Cherbourg, but the 79th and 4th still fell short of their objectives.

Inside Cherbourg, FregattenkapitänWitt continued to oversee the destruction of the harbor. “A vast pall of smoke hung over us,” he wrote, “and explosions continued throughout the night as we tried to deny anything of value to the enemy.”

The 24th proved to be a better day for Collins. He requested naval support and was told that it would arrive the following day. Meanwhile, the 9th Division was able to reach the outskirts of Octeville after destroying some Luftwaffe ground units. With the help of air and artillery support, Wyche’s 79th destroyed a German strongpoint and advanced to the approaches of Fort du Roule, a massive fort that guarded a key access to Cherbourg. The 4th was also successful, with Barton’s men taking the high ground just outside the suburb of Tourlaville.

Von Schlieben, knowing that the end was near, sent a message to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s headquarters indicating that Fortress Cherbourg could not hold out for more than another day or two. He mentioned fortifications being destroyed and heavy losses among unit commanders. Von Schlieben also told Rommel that he had lost communication with several battalions and that morale was plummeting.

Collins gave the German general a chance to surrender on the morning of the 25th. In a message to the fortress commander, Collins noted that Cherbourg was isolated and that American forces vastly outnumbered the Germans. He demanded the unconditional surrender of the city to avoid further losses on both sides. Von Schlieben did not reply.

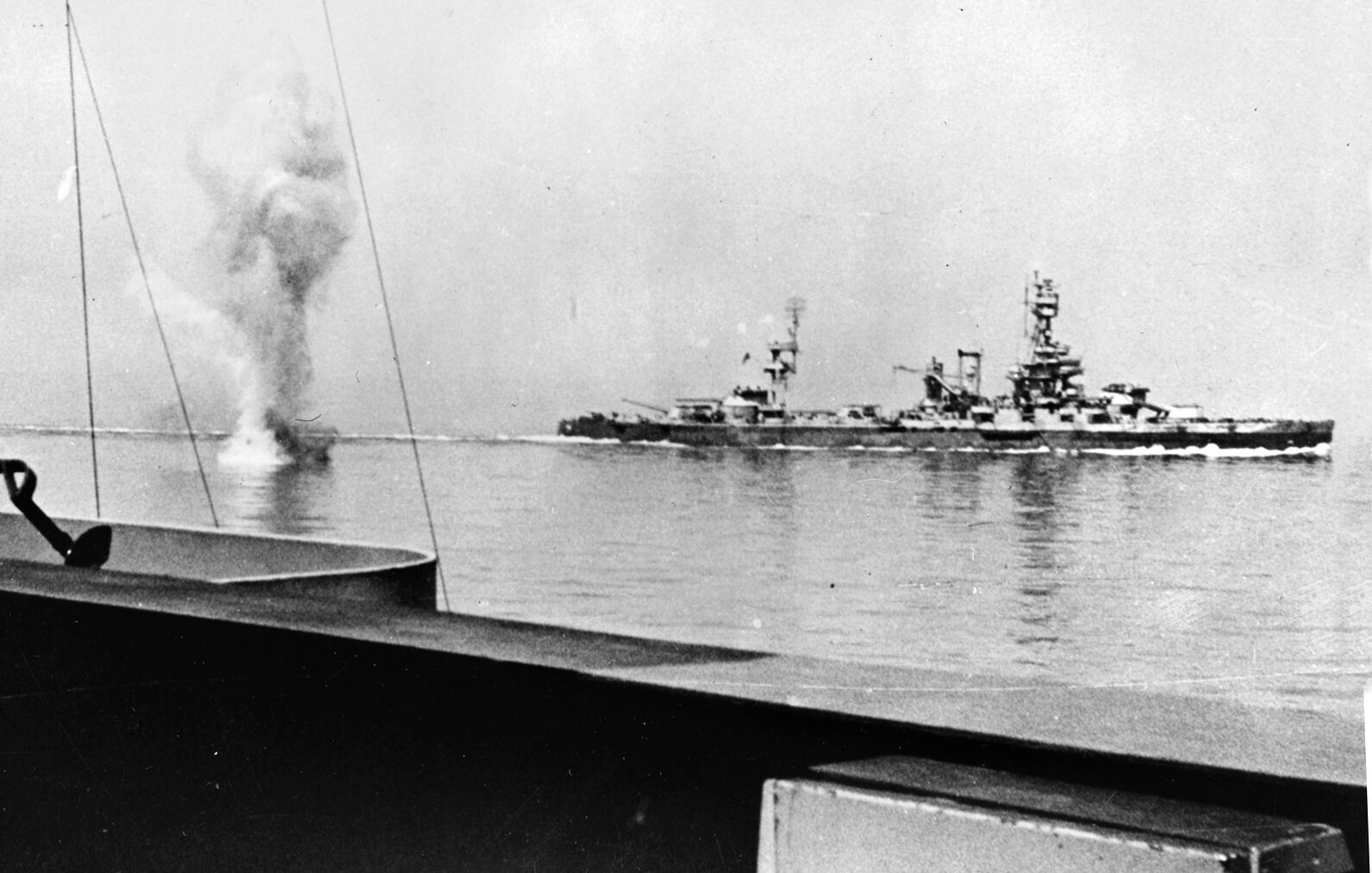

At about 1000 hours, Task Force 120, commanded by Admiral Morton Deyo, arrived off the coast. Deyo had several battleships and numerous cruisers and destroyers at his disposal. His objective was to silence the huge German naval batteries that protected Cherbourg’s seaward side and to support Collins’ attack, which was set to begin at noon. As the clock ticked down, swarms of fighters and bombers appeared over the besieged fortress, ready to drop their deadly loads on designated targets.

Suddenly, the air was filled with explosions as Deyo’s ships moved in to duel with the heavy coastal batteries. Fregattenkapitän Witt watched in fascination as 14-inch shells from the battleship Nevadablasted a battery southwest of Quequerville. Batteries Hamburg, York, and Brommy were also being plastered, but the Germans were retaliating with accurate fire that hit the cruiser HMS Glasgow. Eventually, the battleship Texasand destroyers O’Brien, Barton, andLaffeywould all receive direct hits from the German coastal guns.

The land battle was also now in full swing. In front of Fort duRoule, the 314th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Warren Robinson) watched a succession of P-47 Thunderbolts drop 500-pound bombs on the German position. The bombing was followed by an artillery barrage that did little to damage the fort.

Fort du Roule was a massive structure that contained several levels. Three sides of the fort had been carved out of steep cliffs that overlooked the ocean, and artillery batteries had been placed in the lower levels to ward off any would-be attacker. The landward side was the only practical avenue of attack, and it was strewn with pillboxes and machine-gun nests. Robinson’s men knew that they would be in for a rough day.

After the artillery barrage, Robinson ordered his regiment to advance. His leading battalion was ripped apart by artillery and cleverly concealed German strongpoints that were difficult to detect, even with the maps provided by the French Underground. Its place was taken by another battalion, which continued to fight its way toward the fort.

Meanwhile, Eddy’s 9th had already moved forward to attack the ancient Equeurdreville fortress, which was surrounded by a dry moat. The position was captured by Smythe’s 47th Infantry with the help of air and artillery support and some tank destroyers firing at point-blank range into the fortress. The 9th then continued to advance into Cherbourg’s city limits.

Back at Fort du Roule, the 314th finally broke into the fortress. Savage hand-to-hand fighting took place on the upper level of the fort as Robinson’s men cleared room after room. It was almost midnight before the area was secure, and the day ended with the Americans controlling the upper level and the Germans holding the lower levels.

Explosions rocked Cherbourg during the night as FregattenkapitänWitt continued to carry out the destruction of the harbor. The dock railway station disappeared in a massive blast, and the old tower that guarded the harbor entrance soon followed. Piers and jetties were also obliterated in the attempt to destroy as much as possible.

Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben spent the night listening to pillboxes being destroyed by American engineers. His command bunker was jammed with wounded men, and the air was thick with the stench of death and cordite fumes, which had made their way down ventilation shafts. During the night, he ordered a final message to be sent to the Seventh Army Headquarters: “Last phase of fighting begun. General von Schlieben fighting side by side with his men.”

Collins used the night to reorganize his units. He planned to finish the Germans on the 26th and end the bloodletting once and for all. Colonel Robinson’s men got little rest that night as the Germans in the lower levels of Fort du Roule continued to fire their artillery at the American positions around Cherbourg without letup. “This is the goddamndest situation you ever saw,” said Robinson to a fellow officer.

Thick, black smoke rising from the harbor all but obscured the sun as dawn broke on the 26th. Collins’ three divisions were now fighting inside Cherbourg, gradually pushing the Germans back to the sea, but the battered Kampfgruppenstill fought tenaciously for every yard.

At Octeville, artillery and tank destroyers were hitting von Schlieben’s command center with point-blank fire. A white flag suddenly appeared at one of the entrances, and the Americans ceased firing. A few minutes later, von Schlieben and Hennecke formally surrendered to Maj. Gen. Eddy.

There was one catch to the German surrender. Von Schlieben was only turning over himself and the occupants of the command center. The battle for Cherbourg would continue.

June 26 also saw the surrender of Fort du Roule. Engineer units had spent hours drilling holes in the thick concrete floor of the upper level, and dynamite charges were then dropped on the Germans below, where they exploded with lethal effect. Before the day was over, more than 400 Germans had surrendered and the fort was firmly in American hands.

Collins used loudspeakers to repeat the news of von Schlieben’s surrender and the fall of Fort du Roule, but many of the German defenders still refused to give up while others surrendered without any qualms. Eddy’s division was spared more blood when Port Militaire, Cherbourg’s naval arsenal, surrendered just before a scheduled attack by Smythe’s 47th Infantry.

On the other hand, Fregattenkapitän Witt had relocated to FortWesteck, which held the controls for the demolition of mines in the harbor. Artillery and air strikes hit the fort throughout much of the day, but Witt and his men held on.