By William F. Floyd, Jr.

U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, who was attired in civilian clothing in keeping with his role as an observer for U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, met with U.S. 12th Army Group commander General Omar Bradley at his headquarters in Normandy on August 8, 1944. Standing in front of a situation map, Bradley briefed Morgenthau on Allied plans to surround the German forces of Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge’s Army Group B in a large pocket south of the town of Falaise. Bradley had every confidence that the Allied forces could surround and crush Kluge’s forces in what would amount to one of the greatest decisive victories of World War II.

“This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century,” said Bradley. “We’re about to destroy an entire hostile army.” It was the second day of Operation Luttich, a German counteroffensive underway near the village of Mortain designed to isolate Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army from the bulk of the Allied forces in Normandy.

Morgenthau thought Bradley’s optimism was premature given the resilience of the German Army, but Bradley elaborated in an effort to convince him. If the Germans continued to throw their weight into their attack at Mortain, it would give the Allies sufficient time to seal off the eastern end of the pocket between Falaise and Argentan, said Bradley. As a result of their nearsightedness, the Germans were risking the cream of their forces west of the Seine River. The loss of so many powerful infantry and armored divisions would cripple the Germany Army in France. At that point, the Germans “would have nothing left with which to oppose us,” said Bradley. “We will go all the way from here to the German border.”

The Allies had been bogged down in Normandy since the D-Day landings of June 6. By late July the Allies had 34 divisions on the ground in Normandy, and the Germans had 28 divisions arrayed against them. Since the Allies bore the burden of attacking, their superiority on the ground was only marginal.

Allied forces pushing out from Normandy were organized into two army groups. Bradley commanded the 12th Army Group, which constituted the Allied right wing, and British General Bernard Montgomery led the 21st Army Group, which made up the Allied left wing.

Montgomery served as commander of Allied land forces for Operation Overlord, which lasted from the June 6 landings in Normandy until August 30. General Dwight Eisenhower did not assume the role of supreme Allied commander until September 1. Up to that point, Montgomery was responsible for formulating Allied strategy against the Germans in northern France. Despite this, Eisenhower played an active role advising Bradley throughout August.

After being delayed a number of times by bad weather, Operation Cobra, intended to break the German front at Saint Lo, began July 25. It started with a massive bomber attack that devastated Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein’s Panzer Lehr Division. American infantry and armor swept through Avranches and Coutances. The light resistance they encountered was an initial indication that the German Army in Normandy was weakening. In the first several days of the offensive, the Americans drove the Germans back 12 miles.

Avranches fell on July 30, opening the way west into Brittany, south to the Loire, and east to the Seine and the so-called Paris-Orleans gap. Patton sent Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps to capture Mayenne and Le Mans. The corps covered approximately 75 miles in one week. Patton would rely heavily on the aircraft of Maj. Gen. Elwood Richard Quesada’s 9th Fighter Command to guard the flanks of his fast-moving force from encirclement by superior German panzers. Even if American fighter bombers could not always stop the panzers, they could systematically knock out supply trucks, interrupt logistics, and slaughter German troops.

Although senior German officers recognized that strategic retreat was a real possibility, most believed that their lines would hold. From 1,000 miles away in his East Prussian headquarters, Hitler formulated plans for Operation Luttich. The German leader’s communications with Kluge regarding a possible counteroffensive were intercepted by the British signals intelligence operation known as Ultra.

The intercepts did not give precise information about the time and place of the counterattack, but they revealed that one was under discussion. The British cryptanalysts had intercepted discussions of previous counteroffensives that were ultimately cancelled, so it was hard to tell if this one would go forward. The decoded messages chronicled von Kluge’s vehement objections to the counteroffensive on the grounds that he could not pull out of line enough armored divisions to ensure the success of such an operation. Von Kluge added that such an attack would make the elite German forces involved in it vulnerable to envelopment.

Hitler was adamant that the counteroffensive go forward and brushed aside von Kluge’s objections. “We must strike like lightning,” Hitler said. “When we reach the sea the American spearheads will be cut off. Obviously, they are trying for an all-out decision here, otherwise, they would not have sent their best general, Patton. The more troops they squeeze through the gap, and the better they are, the better for us when we reach the sea and cut them off.”

In preparation for Operation Luttich, the German forces underwent reorganization as six replacement divisions arrived from southern France and from the Pas de Calais region. Panzer Group West was renamed the Fifth Panzer Army under the command of General of Panzer Troops Heinrich Eberbach. After the replacements were distributed, Col. Gen. Paul Hausser’s Seventh Army had 16 divisions, and Eberbach’s Fifth Panzer Army had 12 divisions. Hausser held the German left flank and Eberbach held the right flank. Should the Americans succeed in encircling the Germans, Hausser’s troops would have farther to march than Eberbach’s men.

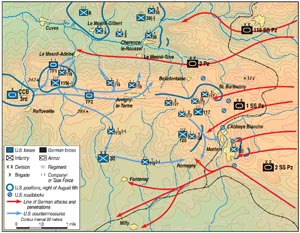

The Germans fought tenaciously to preserve a salient north of Mortain in early August. The increased activity in that sector aroused Bradley’s suspicions that the town would be the jump-off point for a possible German counterattack. The cryptanalysts decoded the first message specifically pertaining to a strike against Mortain at 7:48 pm on August 6, the night of the attack. That message and two more received that evening were passed along to Bradley and the other senior Allied commanders in Normandy.

“Ultra was of little or no value,” wrote Bradley. “It alerted us to the attack only a few hours before it came and that was too late to make any major defensive preparations.”

As it turned out, the full force of the attack fell on Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs’s 30th Division of Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins VII Corps of the U.S. First Army. The VII Corps comprised four infantry divisions (1st, 4th, 9th, and 30th) and two armored divisions (2nd and 3rd).

Hobbs’s men were exhausted from their recent participation in Operation Cobra and had been hoping to be pulled out of the front line themselves for rest and relaxation. Instead, they were transported by truck to their new position and dropped off without maps of the local area. They deployed into the area with slit trenches and foxholes previously occupied by the Big Red One. Moving onto Hill 314 were three rifle companies of the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment. To the 30th Division’s north were other divisions of the VII Corps, notably the 3rd Armored Division, but to the south there were no Americans nearby.

Patton, who previously dismissed Bradley’s concern over a German counterattack, realized by the night of August 6 that something was afoot. Although he felt the Germans were bluffing, he nevertheless issued orders to three divisions in the vicinity of St. Hilaire, situated 10 miles southwest of Mortain, to halt their advance until further notice in case they had to turn north to assist the First Army.

Hausser had two Wehrmacht (2nd Panzer and 116th Panzer) and two SS armored divisions (1st and 2nd SS Panzer) at his disposal. The divisions had among them a total of 250 tanks. Luftwaffe officials had promised to send as many as 300 aircraft to support the attack. Mortain, a town of 1,600 residents nestled in a valley, was about 20 miles from Avranches. The key to success for the Germans would be to quickly eliminate any American roadblocks and secure the crossroads needed to keep the tanks and half-tracks moving. What is more, the Germans would need to control the high ground surrounding Mortain. In particular, they needed to capture a rocky prominence known as Hill 314, situated just east of Mortain. Because the hill afforded sweeping views of the surrounding countryside, it was of great value to artillery spotters.

The stakes of the Mortain counteroffensive were high, for if von Kluge succeeded in reaching Avranches he would isolate as many as 12 American divisions. Lt. Gen. Gerhard Graf von Schwerin, the commander of the 116th Panzer Division, objected to the counteroffensive, and his division did not join the attack until well into the afternoon of August 7.

Shortly after 1 am on August 7, American pickets began hearing small arms fire followed by the unmistakable sound of rumbling tanks. Oberführer Otto Baum’s 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, outfitted with formidable Panther tanks and Wespe self-propelled howitzers, spearheaded the German attack against Mortain. Das Reich advanced in three columns against the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment holding Mortain.

Hausser hurled half his tanks against the Americans on the first day of the counteroffensive. Altogether 26,000 Germans participated in the Avranches counteroffensive. German panzers came clanking out of the darkness at 12:38 am on August 7 against the troops of the Old Hickory Division. The Germans had begun shelling the American positions earlier that evening, and many of the buildings in Mortain were ablaze at the time of the attack. In addition to long-range guns, the Germans also employed the brutally efficient 88mm guns in direct fire support.

Supported by the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division, the black-uniformed SS troops of Das Reich overran Mortain in the first hours of the attack. The Americans employed bazookas to augment the machine guns and antitank guns in place to defend their roadblocks. The Germans repeatedly probed Hill 314 the first night, but the 700 Americans entrusted with its defense drove them off.

The advantage shifted to the Allies when the sun rose that morning. British Typhoons and American P-47 Thunderbolts took to the skies to knock out as many German tanks as possible. The Typhoons were armed with a combination of 60-pound rockets and four 20mm cannons. The P-47s were armed with 4.5-inch rockets and eight .50-caliber machine guns. The Allied fighter bombers knocked out an estimated three dozen tanks on the first day of the German counterattack. In so doing, they helped alleviate the pressure on the riflemen of the 30th Infantry Division.

Only the return of night stopped the awesome carnage inflicted by the Allied fighter bombers. Although some Luftwaffe bombers managed to strike the American positions on the first night of the attack, Quesada’s fighters shot down any Luftwaffe fighter aircraft that attempted to fly into the sector during the daytime. Altogether, the pilots of the 9th Fighter Command flew 429 sorties on August 7.

“We found an entire German armored column that was 15 miles long,” said William Dunn, a pilot with the 406th Fighter Group of the XIX Tactical Air Command. “After hitting this column with our full group strength three times during the day … the road was jammed by burning, exploding, and destroyed tanks, trucks, and armored personnel carriers.”

Defending the battlefront between Mortain and St. Barthelemy to the north were the three battalions of the 117th Infantry Regiment. An American platoon defending the crossroads at Abbaye Blanche, the site of a Benedictine convent just north of Mortain that had been converted into a Cistercian monastic church in the 12th century, had four 3-inch antitank guns, a 57mm gun, bazookas, flamethrowers, and machine guns with which to blunt the German attack. The guns were sighted to cover bridges over the Cance River.

The sun was beginning to rise at 5 am when the lead elements of the Der Führer Regiment of Das Reich began its assault on the defenders of the crossroads. The Americans knocked out the reconnaissance vehicles that approached the roadblock and stitched the fleeing Germans with .30-caliber machine-gun fire. American tank destroyers moved up to reinforce the platoon engaging the enemy’s Panther tanks at close range. They succeeded in some cases in knocking out Mark IV and Mark V Panther tanks by firing back at their muzzle flashes. The Americans employed cunning tactics; for example, at one roadblock they let the German armor pass through and then attacked the panzergrenadiers following the tanks.

The 2nd Panzer Division made the greatest penetration at the outset of the German attack. Led by its gifted commander, General of Panzer Troops Heinrich Freiherr von Luttwitz, the division advanced four miles on a narrow front in the St. Barthelemy sector. Luttwitz’s panzer troops overran two companies of the 117th Infantry Regiment before its advance was halted by American artillery.

As early as 1 pm on August 7 the German attack began to bog down. Over the next four days, the German panzer troops were reduced to fighting a grinding battle of attrition with Hobbs’s infantry regiments.

The doggedness of the American infantrymen at Abbaye Blanche on the first day of the battle forced Baum to redouble his efforts to seize the key position. He surmised that control of the crossroads was necessary to isolate the Americans atop Hill 314. He ordered repeated company-sized attacks against the hill. Despite the valiant effort of the panzergrenadiers, the Germans failed to carry Hill 314. The American stand atop the key ground was made possible by the support of five artillery battalions. The heavy guns shattered repeated attempts by Das Reich and the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division to capture the strongpoint.

The German counteroffensive ended on the night of August 11-12. The defeated German columns withdrew east and north. In keeping with his characteristic fashion of blaming his generals, Hitler said, “The attack failed because Field Marshal von Kluge wanted it to fail.” Hobbs’s 30th Division paid a high price to defeat the German counteroffensive. It suffered 1,800 casualties in the slugfest with the four panzer divisions.

While the German counteroffensive was in progress, Montgomery proceeded with his own offensive. On August 8 the Canadian First Army attacked south from Caen. The two-day offensive had as its objective securing Falaise, which lay nine miles to the south.

The Germans were waiting, though. They fielded dozens of 88mm guns in an effort to stop the Canadian tanks. Fighting alongside the Canadians was the newly deployed Polish 1st Armored Division.

On August 8, while the battle for Mortain and Operation Totalize were both raging, Bradley became captivated with the idea of trapping the German forces between Argentan and Falaise in what became known as the short envelopment. Bradley called Montgomery to outline the plan. Eisenhower was highly enthusiastic about the revised plan. From a strategic standpoint, he thought it made perfect sense. “We must destroy the enemy rather than win territory,” he said, adding that it should be done “now and not tomorrow.”

Montgomery tentatively agreed, although he still favored a larger envelopment already planned near the Seine River. Although he was even more skeptical than Montgomery of Bradley’s plan, Patton went along with it. He offered to divert Haislip’s XV Corps north toward Alençon and Argentan to rendezvous with the First Canadian Army south of Falaise. The stakes were high for the Germans for they stood to lose a significant portion of their 100,000 troops in Normandy.

The Americans began their own counterattacks on August 9 seeking to regain ground lost to the Germans on the first two days of their counteroffensive. To buttress the 30th Infantry Division, Collins ordered elements of the 3rd Armored Division and the 4th Infantry Division to recapture towns, such as Juvigny-le-Terte, behind the main line of resistance that had fallen to the Germans in the past two days. In addition, Maj. Gen. Paul Baade’s 35th Infantry Division of the Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps began fighting its way north toward Mortain.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Walton Walker’s XX Corps, which was advancing on Patton’s right flank, moved into the Loire Valley. The 5th Infantry Division, led by Maj. Gen. Stafford Irwin, pushed south from Vitre toward Angers, which lay 60 miles away at the confluence of the Maine and Loire Rivers. The Red Devils, as Irwin’s division was called, advancing on Third Army’s extreme right flank, reached Angers on August 10 and began clearing out the Germans defending the town.

Across Haislip’s front the Americans encountered only minor resistance. Leading XV Corps’ advance were two armored divisions. Maj. Gen. Jacques Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored Division advanced on the left, and Maj. Gen. Lunsford Oliver’s 5th Armored Division advanced on the right. They were followed by the 90th and 79th Infantry Divisions, respectively.

Leclerc’s troops secured the bridges over the Sarthe River at Alençon on August 12 and continued their advance, leaving the 90th Infantry Division to mop up in Alençon. The day’s actual objective had been Argentan, even though it lay 12 miles inside the sector assigned to Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. At that point, Haislip ordered Leclerc to angle west. This would open the highway north from Sees for the 5th Armored Division, giving greater weight to the Allied attack. Instead, Leclerc decided to put his forces on all available roads, thus blocking the movement of the 5th Armored’s fuel trucks. This move by the French also gave the Germans six hours to rally 60 panzers from the area around Mortain for the retreat east.

The Canadians had become badly bogged down trying to reach Falaise. Patton intended to order Haislip to attack the German blocking force facing the Canadians and push on until he linked up the Canadians near Falaise. The Third Army commander phoned Bradley on August 13. “Shall we continue and drive the British into the sea for another Dunkirk?” Patton asked sarcastically.

Bradley was a serious as Patton was jocular. He ordered Patton not to go beyond Argentan. “Just stop where you are and build up on that shoulder,” said Bradley. The British later learned of Patton’s quip, and they were justifiably offended.

Bradley’s decision was based on questionable intelligence. He believed that as many as 19 German divisions were racing east to escape the Allied trap. If this turned out to be true, Haislip’s corps was at risk of destruction if it were to move north with an exposed left flank.

Montgomery also fretted over the vulnerability of Haislip’s corps. Bradley did not consult with Montgomery; he alone made the decision to stop Patton. It came as no surprise to Bradley that Patton objected. Haislip could “easily advance to Falaise and completely close the gap,” wrote Patton. He said the halt was “a great mistake.”

Bradley defended his decision. “Although Patton might have spun a line across the narrow neck, I doubted his ability to hold it,” Bradley later wrote. “Nineteen German divisions were now stampeding to escape the trap. Meanwhile, with four divisions [Patton] was already blocking three principal escape routes through Alençon, Sees, and Argentan.”

Bradley reasoned that if Patton extended the line to include Falaise, it would have extended his roadblock 40 miles. That would have allowed the Germans an opportunity to punch through the perimeter. On those grounds, it was imperative that Haislip stop at Argentan. “I much preferred a solid shoulder at Argentan to the possibility of a broken neck at Falaise,” wrote Bradley.

The failure of Operation Totalize to capture Falaise caused more debate than almost any other action during the battle for Normandy. Montgomery had made a major miscalculation when he felt the Canadians would be at Argentan before the American forces could arrive. He also assumed the Germans would move more troops to defend their southern flank against Patton. Moreover, Montgomery also had underestimated the difficulties of sending untried armored divisions against a strong force of 88mm guns.

At that point, Bradley made another key decision. He decided to dispatch more than half of Haislip’s force, two divisions and 15 artillery battalions, toward Dreux, which lay 65 miles to the east. “Due to the delay in closing the gap between Argentan and Falaise, it is believed that many of the German divisions which were in the pocket have now escaped,” Bradley stated in his August 15 order. “In order to take advantage of the confusion existing, the Third Army will now initiate a movement toward the east.”

As of August 15, the Germans still had not decided whether to evacuate the Falaise Pocket. For several days Hitler had been hoping that his army in Normandy would be able to regroup and attack Haislip’s left flank, halting the American advance. The remnants of the German Army were absorbing overwhelming punishment from ground and air in practically all areas of the pocket, making a counterattack completely out of the question. Based on these circumstances, Hitler finally authorized a complete retreat from Normandy that day.

Von Kluge and the other German generals in Normandy already had been shifting their troops eastward in the face of heavy attacks. When Hitler’s order arrived at the front on August 16, German troops began an all-out effort to get out of the rapidly closing pocket. This involved crossing both the Orne and Dives Rivers to reach the Seine River. Bradley would concede afterward that if he had not been misled by intelligence he might have sent Walker’s XX Corps north to deploy on Haislip’s right flank in the direction of Chambois.

The Falaise Pocket by this point extended 20 miles from east to west and was 10 miles wide. Allied intelligence had intercepted von Kluge’s withdrawal order, correcting Bradley’s decision that the Germans had already fled. This prompted Montgomery to ask the American forces to shift eight miles northeast from Argentan toward Chambois and Trun to a location where the Polish and Canadian troops were bound from the northwest in hopes of closing the remaining two roads the Germans were using to exit the pocket.

On August 17 Montgomery told Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, the chief of the British Imperial General Staff, that the gap had been closed. It was a false statement. In addition, he told British Prime Minister Winston Churchill that the Germans trying to exit the pocket would not be able to escape. It was another falsehood.

Moreover, Montgomery also would claim that he had 100,000 Germans nearly surrounded. This was partially true; however, reducing the pocket from the air and ground had begun. As the fighting near Falaise heated up, Allied aircraft flew between 1,500 to 3,000 missions per day.

Trun fell to Canadian forces on August 18, leaving the Germans with an escape corridor that was only 10 miles wide. Von Kluge was startled that night when Field Marshal Walther Model arrived with orders that he was to replace von Kluge as the commander of Army Group B. Until Model arrived, von Kluge had no inkling he was about to be dismissed. Model gave von Kluge a handwritten note from the German leader. The note ended with a threateningly ambiguous comment that the field marshal should contemplate which direction he wished to go. Von Kluge would write a letter to Hitler telling him that the “failure of the armored units in their push to Avranches and the consequent impossibility of closing the gap to the sea had been preordained by the American and British wealth in material.” He concluded by urging Hitler to end the war. Von Kluge departed for Germany, but en route committed suicide with a vial of potassium cyanide.

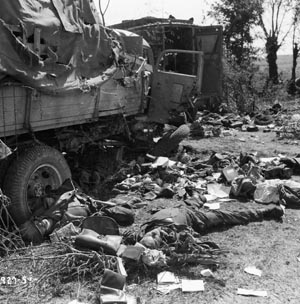

With time running out and the major roads blocked by Allied forces, the remnants of the German Seventh Army hurried east on farm roads or simply headed cross-country using their compasses to guide them. Many of the haggard Germans lacked helmets and shoes. As many as 3,000 Allied guns pummeled the Germans trapped in the pocket. Based on information received from aerial spotters, the gunners used devastating white phosphorus and high-explosive rounds. Those targets that the Allied howitzers missed were soon found by Allied fighter bombers. The relentless Allied air attacks, coupled with the lack of available fuel, compelled German crews to abandon their armored vehicles.

The conditions were horrific, and the scenes that confronted the Allies and Germans alike were stupefying. “The roads were blocked by shot-up and burned-out vehicles standing side by side,” wrote an officer with the 21st Panzer Division. “Ammunition exploded, panzers burned, and horses lay on their backs kicking their legs in their death throes. The same chaos extended in the fields far and wide. Artillery and armor-piercing rounds came from either side into the milling crowd.”

During the daytime German soldiers and vehicles hid in the woods and orchards from Allied aircraft, waiting for nightfall to resume their flight. Those on foot stumbled along at night cursing their commanders for a litany of perceived failings. They found themselves mixed up with rear-echelon troops, all trying to escape but without any idea of where they were going. The ground shook as Allied batteries shelled the roads to hamper their escape.

The Germans launched a savage counterattack on August 19 against the Canadian 4th Armored Division at St. Lambert, a village straddling the Dives River between Trun and Shambles. Fire from burning gasoline trucks blackened the sky. At a bridge across the river there were corpses, carcasses, and burned-up equipment. The Germans organized small battle groups to fight their way through an Allied cordon southeast of St. Lambert. The effort succeeded.

Three miles to the northeast, 1,800 men of the Polish 1st Armored Division entrenched on a key position known as Hill 262. The Poles became embroiled in a major firefight on August 20 with elements of Das Reich and Colonel Max Sperling’s 9th Panzer Division. Model sent these two divisions west across the Seine River in an effort to reinforce those units still inside the pocket and help extract them from the closing Allied pincers that threatened to trap them. The resilient Poles fought valiantly.

The weather cooperated with the Germans. Low clouds grounded Allied Typhoons and Thunderbolts that day. German Panthers and Polish Shermans exchanged fire at point-blank range as infantry units fought continuously for two days. As the fighting raged, Germans retreating east streamed past Hill 262 (also known as Mont Ormel). By the time the Canadian 4th Armored Division broke through on August 21, 350 Polish soldiers lay dead and more than 1,000 were wounded. The hulks of destroyed tanks littered the landscape.

German troops continued to perish as they sought to cross the Dives. Some grew weary of flight and surrendered. Several hundred Germans in armored scout cars firing 20mm guns attempted to charge through fields around Trun. A Canadian line of Vickers machine guns raked the vehicles, inflicting substantial casualties. As the battle progressed, it was the Canadians and Poles who bore the brunt of the fighting, not the British and Americans. The 1st Polish Armored Division bled heavily in sustained fighting with the Germans for control of Hill 262. At mid-day on August 21, Canadian forces arrived at Mont Ormel to relieve the Poles.

Although the Allies had won a clear victory over Germans at Falaise, the victory was incomplete. The Germans who survived the pocket had little trouble getting over the Seine River farther east where they crossed at as many as 60 locations. The Germans constructed two ferries to get upward of 25,000 vehicles to the east bank of the Seine over a four-day period beginning August 20.

Meanwhile, German foot soldiers nailed together rafts from barrels, pried doors from their hinges and mounted them on empty fuel cans, and tied saplings together with phone wire to float across the Seine. Others employed even more desperate measures, such as clinging to bloated cow carcasses to float across the river.

Nothing the Germans had accomplished rivaled Falaise, said General Fritz Bayerlein, a Panzer division commander in Normandy, summing up Patton’s armored thrusts in France. “Not even the battles of annihilation of the 1940 blitzkrieg in France in or in 1941 in Russia can approach the battle of annihilation in France in 1944 in the magnitude of their planning, the logic of their execution, the collaboration of sea, air, and ground forces, the size of the theatre, the strength of the combatants, the bulk of the booty, or the hordes of prisoners,” Bayerlein wrote. “Its greatest importance, however, consists in its strategic efforts, that is, that it laid the foundation for the subsequent final and complete annihilation of the greatest military state on earth.”

The German armies in France were in no way completely destroyed in the Falaise Pocket. On the river below Rouen in eastern Normandy, a five-mile-long line of undamaged German armor and vehicles sat stopped for an entire day and night. They were waiting while German engineers worked on repairing a damaged railway bridge, the only possible way to cross the river. Heavy rain had kept the Allied air forces grounded for the time being. Sporadic artillery fire inflicted some losses, but thousands of men and vehicles were soon travelling toward Germany. The Germans who made their way out would prove invaluable to Hitler in the coming weeks, forming the skeleton on which the western defense of the Reich would be based.

“We were shell shocked and exhausted,” wrote 1st SS Panzer Division Major Herbert Rink. “Once behind the West Wall, we could join all the defeated, decimated German units, all those who had made it through 600 kilometers of horrifying crushing battles…. We, who had come depleted and exhausted from the inferno of Caen, through the breakout from the pocket at Falaise, through the nerve-racking defeat across France, and partisan-plagued Belgium—we had gathered our strength and rebuilt our confidence.”

Eisenhower described the battlefield of Falaise as one of the greatest killing fields of all time. “Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap, I was conducted through it on foot to encounter scenes that could be described only by Dante,” wrote Eisenhower. “It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.”

The Germans abandoned Paris without a fight. Leclerc’s French 2nd Armored Division arrived in Paris on August 25 to find the French Resistance in control. From that point forward, the Allies plotted their strategy for carrying the war into Belgium to liberate Brussels.

One of the most important reasons for the Allied success in France was the lackluster response of the German Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. The Luftwaffe had withdrawn most of its remaining planes from France, and the Kriegsmarine was outmatched by the combined Allied navies. The fractured German command structure also contributed to the German defeat in France. Simply put, Hitler’s involvement proved a hindrance to strategic operations.

The inability of the Allied leaders to throw caution to the wind in the Battle of the Falaise Pocket, as Patton had urged, resulted in a great missed opportunity for the Allies failed to close the pocket, thereby forcing the Germans to surrender, as they had at Stalingrad, or face annihilation.

Even after the fighting at Falaise was over, the Allied leaders remained hidebound. They remained fixated on liberating Brittany, even though the offensive into that region amounted to little more than a sideshow. For that reason, they insisted that Patton carry out the plans established before the D-Day landings. The plan called for Patton to move the entire Third Army toward Brittany. Patton protested that sticking with the original plans was a mistake. He wanted to attack toward Germany, not away from it. Eisenhower and Bradley made one concession. They allowed Patton to reduce his offensive in Brittany by one corps. This left two corps to pursue the Germans retreating toward Germany.

Germans casualties in the Falaise Pocket amounted to 30,000 killed and wounded and 50,000 captured. In contrast, the Allies suffered 10,000 casualties. In addition, the Germans lost nearly all of their fighting vehicles. Specifically, they lost 220 tanks, 160 assault guns, 700 towed artillery pieces, 130 antiaircraft guns, 130 half-tracks, 5,000 motor vehicles, and 2,000 wagons.

The battle destroyed German resistance in Normandy. Model told Hitler that his panzer and panzergrenadier divisions only averaged between five to 10 tanks. Many of the German divisions that reassembled east of the pocket had only about 300 soldiers, although a few had upward of 3,000 men. Das Reich, for example, emerged from the Falaise Pocket with only 450 men and 15 tanks.

The one ray of hope for the Germans was that most of their divisions and corps headquarters units managed to escape relatively intact. The Germans lost only three of their 15 divisional commanders and one of their five corps commanders. This enabled the Germans to quickly reorganize the survivors of the battle for the hard fighting in which the Allies would have to pry the Germans from their superb defensive positions along the border of the Fatherland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments