By Brig. Gen. (ret.) Raymond E. Bell, Jr.

Before World War II, the Belgian port city of Antwerp was one of the world’s great ports, ranking with those of Hamburg, Rotterdam, and New York. Antwerp is located some 55 miles up the Scheldt (Schelde) Estuary from the North Sea. Five hundred yards wide at its location on the estuary, the port’s minimum depth along its quays is 27 feet, deep enough to handle the largest ships in the world—especially when it comes to maneuvering such vessels into place along the quays.

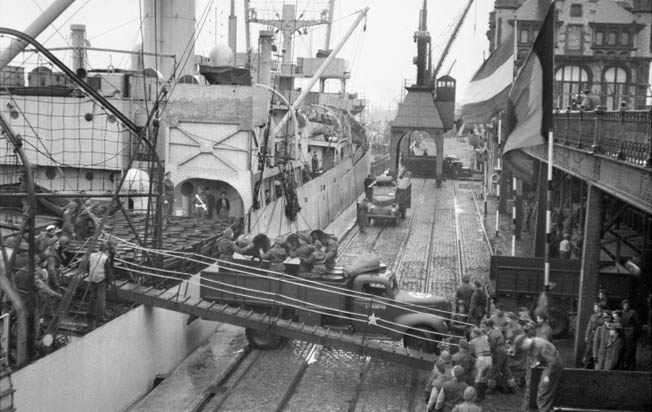

The port’s capacity is prodigious; in 1944 alone there were nearly 26 miles of quays that were serviced by 600 hydraulic and electric cranes, in addition to numerous floating cranes, loading bridges, and floating grain elevators. Extensive storage accommodations around the port and excellent road and rail clearance facilities were available. And on September 4, 1944, although in German hands, the port’s facilities were virtually undamaged and fully functioning.

For the Allies, after their breakout from Normandy, it was vitally important that Antwerp be captured and placed in operation as soon as possible. If the war in northwestern Europe was to be concluded expeditiously, the port would play a key role in supplying both British and American army groups.

Distance from the Normandy beaches alone made the seizure critical. To supply Allied forces advancing from Normandy, trucks had to travel 400 miles over roads. Most importantly, the Antwerp port was only 65 miles from the principal Allied army logistic depots at Liege, Belgium.

The distance was even shorter to service the U.S. Third Army depots at Nancy, France, from Antwerp (250 miles) than it was to do so from Cherbourg (400 miles), the latter having to use the “Red Ball Express” system on the overtaxed motor road network. (See WWII Quarterly,Summer 2010.)

In terms of logistical support, the use of Antwerp meant that 54 divisions could be supplied, as compared to only 21 using Cherbourg—while the ports along the English Channel coast were of only limited capacity.

The result was that the effort to support an Allied division by way of Antwerp was calculated to be only a third of that required to sustain one by way of Cherbourg. It is no wonder then that in a communication to British Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, General Dwight D. Eisenhower stated unequivocally, “Of course we need Antwerp.” But there were problems.

On August 27, 1944, when the Germans were in full retreat from the Normandy battlefield, soon to be Field Marshal Montgomery ordered his XXX Corps to advance to the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary in Belgium. He did not specify that the corps was to stop there, but he made it known the key objective was the capture of Antwerp. The mission was given to British XXX Corps commander Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks, who in turn gave it to Maj. Gen. George Philip Bradley “Pip” Roberts, commanding the British 11th Armoured Division.

After a tough beginning around the Norman city of Caen, where its combat with German armor had tended to make the division’s tankers overly cautious, the 11th Armoured soon began to overcome any lethargy it had accrued in those battles. Reminiscent of its dynamic training during the first 18 months of its formation under its first commanding general, Maj. Gen. Sir Percy Hobart, the division quickly moved into an overdrive mode, advancing northeastward through France into Belgium.

By September 1 the division had bounded forward 40 miles from the French city of Amiens. By 11:30 am on September 2, the 11th had rolled into Lens in northern France and, after having pushed four miles farther on, the Second British Army ordered the division to “stand fast” for the rest of the day to resupply its elements. Then, on September 3, in Operation Sabot, the division struck out for Antwerp.

In the early afternoon of September 4, after a sprint of 100 miles, elements of the 11th British Armoured Division’s 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (3 R Tanks) reached the outskirts of Antwerp. It found the way into the city blocked at its main bridge by mines and machine-gun positions.

Reacting swiftly under the cover of a smoke screen, the tankers circumvented the obstacle and an armored battalion, and along with a company of the Rifle Brigade infantry, sped into Antwerp with one of its tank squadrons reaching the port’s vast harbor. There the British found that the entire dock area was in an undamaged condition and quickly took possession of it.

The swiftness of the division’s advance had surprised the German commander, Generalmajor Graf Christoph Stolberg-zu-Stolberg, who, on being captured, confessed he had not expected the sudden British arrival and thus had been unable to demolish the port’s facilities.

Stolberg’s failure was enhanced by the actions of a Belgian reserve lieutenant—apparently his military affiliation was unknown to the Germans—employed in his civilian capacity in the port administration office. He was able to work out a scheme that would effectively neutralize the German demolition plans if Stolberg had ordered an attempt to execute them. Seizing the surprisingly undamaged port was a tremendous victory—or so it seemed.

But the 11th Armoured Division stopped in place in Antwerp and rested after its arduous advance. In its great leap forward, the division did not try either that day or the next to seize the bridges over the Albert Canal, which were key to any further advance.

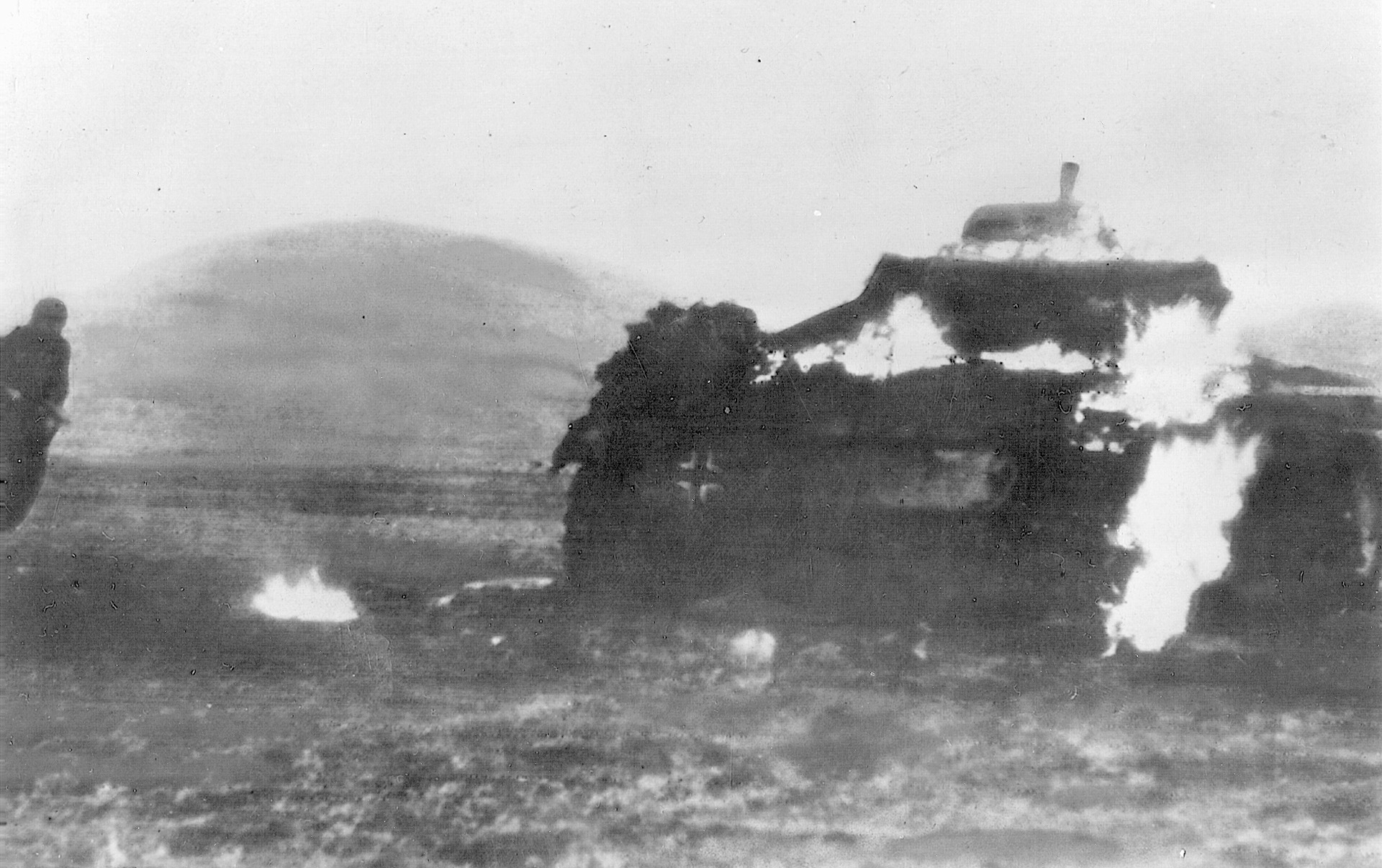

On September 6, the 4th Battalion, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (4 KSLI), crossed the canal, but by then the Germans had blown the bridges. An enemy counterattack by infantry and five tanks isolated the 4 KSLI in a factory complex, and the British infantry, incapable of ferrying some antitank guns across the canal, was forced to withdraw; a temporary stalemate ensued.

The report that Antwerp had fallen on September 4 to the Allies caused great consternation in Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia. The Germans clearly recognized the importance of Antwerp in that it would solve the obvious logistic challenges the Allies were facing in their rapid advance north into Belgium and farther into Germany.

At the time, Field Marshal Walther Model, commanding Army Group B, believed that the fast-advancing British armor would further exploit the port’s capture by moving along the Scheldt’s northern bank, clean it up, and take over the entire South Beveland peninsula and Walcheren Island on the North Sea.

Also compounding the critical German situation at the beginning of the first week in September, only a few replacement and rear-area units defended the line along the whole Albert Canal from Antwerp in Belgium to Maastricht in Holland. It seemed that unless the Allies were blocked along that line the “door to northwestern Germany stood open.”

Hitler’s reaction to the news that Antwerp had been captured virtually intact was immediate. The Germans well knew that Antwerp’s port capacity, if delivered to the Allies in its untouched condition, would be a major victory for them. While the local German commander, with few resources available, launched a counterattack to defeat the attempted British lodgment over the canal on September 6, Hitler also moved quickly.

Into the seam between the German Fifteenth Army withdrawing along the French and Belgian coast and that of Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies retiring generally northeast, Hitler ordered the newly organized First Parachute Army, commanded by Generaloberst Kurt Student, to move to the Netherlands and defend the canal lines running through Antwerp.

Generaloberst Gustav von Zangen was also recalled from Italy to take over the German Fifteenth Army; he received orders to defend the south bank of the Scheldt. In addition he saw that troops were moved into the fortified English Channel port cities of Dunkirk, Calais, and Boulogne. At the same time, Zangen initiated the transport of as many men as possible to the Scheldt’s north banks so they could take up new positions elsewhere in front of the advancing Allies.

With the assistance of the German Navy, he succeeded in moving most of the army along with some 500 artillery pieces over the estuary to the north bank of the Scheldt, an important accomplishment that was soon to benefit the Germans, whose front elsewhere seemed to be collapsing.

The Germans also had an ace in the hole that was soon to play itself out. Before Antwerp’s port facilities could be used, the 55 miles of the Scheldt Estuary waterway and its banks had to be cleared to allow ships to pass through from the North Sea.

As early as September 3, as the British raced into Belgium, the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief, Expeditionary Force gave warning that both Antwerp and Rotterdam were highly vulnerable to blocking and mining. If the enemy succeeded in accomplishing these missions, he could not estimate how long before the port could be used.

Although Antwerp, with its considerable port capacity, had been captured on September 4 by the British Second Army’s 11th Armoured Division, the 1st Canadian Army advancing along the French coast was making slower progress. German garrisons in the coastal port cities were holding out and, although being bypassed by the Canadians, were still impeding Allied forward progress.

These cities were not only thorns in the side of the Allies, as the Germans starting on September 6 were able to evacuate a large number of their troops from the Dutch south bank port of Breskins to Flushing on Walcheren Island.

Generalmajor Walter Poppe, commanding the splintered and weak German 59th Infantry Division, was astounded that, by using a couple of small Dutch vessels and several Rhine River barges as well as numerous boats and even rafts, it was possible to get not only the artillery and men, but vehicles and horses across the three-mile-wide Scheldt Estuary without Allied naval interference. With much of the evacuation occurring at night, the Germans were able to largely negate the impact of Allied air activity as well.

While German reinforcements were being rushed from the Netherlands and Germany, time was also being gained to strengthen German positions along the Scheldt. Retreating German Fifteenth Army troops were able to hold the Canadians south of the Leopold Canal in Belgium into October, which prevented the Canadians from reaching the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary.

Although the Germans may not have had troops in position to block the move into Germany at that time, their situation at Antwerp was better than they probably realized. To prevent the port of Antwerp itself from being viable for logistics purposes, its capture was almost immaterial at the time because of the extensive estuary mining and fixed German defenses along the Scheldt’s banks.

Initially, the Germans also had been more concerned about an assault from the North Sea so, at the time Antwerp was captured, their land defenses were pointing principally toward the sea. Once it was known that Antwerp had been captured, the Germans were able to take advantage of the slower progress of the Canadians and redirect those defenses on the south bank of the Scheldt, and repositioning them along the Leopold Canal.

The limited German counterattack on September 6 and the destruction of the canal bridges closed a narrow British window of opportunity to advance farther. While freeing the south bank of the Scheldt was, at the moment, out of the question because of German resistance to the south and along the Leopold Canal, between September 4 and 6 a determined push by the 11th Armoured Division to the north and west along the north bank of the Scheldt had remained an option open to the Allies.

A swift strike after seizing the Albert Canal bridges intact across the South Beveland isthmus on to Walcheren Island had the potential for isolating the Germans on the Scheldt’s south bank and expediting the clearance of the estuary, resulting in the opening of the port.

Tactically, when the opportunity presents itself, forging a bridgehead over a waterway in the face of light resistance is a sound move. Halting short of such an obstacle allows the opponent time to strengthen and reinforce his position, thus making it harder and more expensive to cross and breach it in the long run.

On the afternoon of September 4, once the Antwerp port facilities were so quickly overrun, the question arises why the British didn’t take the advantage to cross the bridges and continue the advance. German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, whom Hitler had dispatched to take over command of OB West (German West Front Command) from Field Marshal Model on September 4, for one, noted that for 36 hours the British did not move north of Antwerp. It appears that the basic military maxim—exploit success—had been violated by the Allies.

The men of the 11th Armoured Division were tired after their marathon run to Antwerp. Their tanks, of which only 90 Sherman medium and 15 Stuart light tanks were considered fit for combat out of an original strength of 200, were in need of maintenance. Fuel, food, and ammunition resupply, potentially hindered by a long logistics tail, were required. There were significant reasons, therefore, for a standdown by the division’s armored troopers.

But the division was not on its last legs. It had the momentum behind it to keep moving and exploit its stunning success. The XXX Corps commander, Horrocks, was leading the charge toward Antwerp and Brussels. He reputedly “commanded the Corps from one tank with one staff officer and one A.D.C. [aide-de-camp],” and while doing so was in position to positively influence his units’ employment. The Albert Canal bridges, as a minimum, were for the taking by rapidly advancing British troops.

Instead, it appears that it was a matter of the mind and perceptions as to what the capture of the port city was to achieve. In The Tanks,author B. H. Liddell Hart explains: “When the 11th Armoured Division raced into Antwerp on the 4th, its commander’s mind, following his instructions, was concentrated on the capture of the docks.… He did not try to seize the Albert Canal bridges on the northern edge of the city with a view to further advance.

“The divisional history says: ‘Had any indication been given that a further north was envisaged, these might have been seized within a few hours of our entry into the city.’ The Corps Commander’s mind was likewise concentrated on the capture of the docks. Moreover he had been told not to advance any further than Antwerp for the moment, until supplies caught up—his orders were to ‘refit, refuel, and rest.’

“That was a sound course if there had been any serious opposition ahead, but such did not exist at the moment—as was, in fact, correctly gauged by XXX Corps and the higher commands. Thus the omission to seize the Albert Canal bridges would seem to have been primarily due to concentration on the immediate objective and the dazzling effect of the triumphant race to gain it.”

Obviously, the strategic logistic implications of the capture of Antwerp and the halt there were, at the moment, not realized by those on the ground in combat with the enemy.

But what about those at the highest command echelons? The matter appears to be more confused at those levels than it was at the 11th Armoured Division level, which had accomplished its mission of swiftly seizing the Antwerp dockyards.

There is no doubt that the capture of the Antwerp port facilities offered important potential solutions to the severe logistical situation, which was having a big impact on the Allies’ sweep toward Germany. But there were other considerations, and they went all the way up to Eisenhower and Montgomery.

Montgomery may have been the master of the “set-piece battle,” but he was also decisive when it came to making big decisions. For example, while the Allied high command was dilly-dallying around in North Africa about what the plan for assaulting the shores of Sicily in 1943 in Operation Husky should be, it was Montgomery who forced the decision as to how it was to be done.

Later, when planning to execute Operation Neptune/Overlord on June 6, 1944, Montgomery did not hesitate, as did others gathered around Eisenhower, to say “Go!” when the dicey weather situation was the primary factor in the launch of the Normandy invasion. Indeed, it was Montgomery who determined that five divisions instead of three would land over the beaches of Normandy on D-Day.

So it was that he was so insistent on a plan to strike northward into the heartland of Germany in a single 40-division-strong thrust once German resistance in France collapsed, which would thereby win the war.

On August 17, as the Americans and French in the south and the British, Canadians, and Poles in the north started to close the gap around Falaise and Argentan in Normandy, Montgomery at his command post at Le Beny Bocage near Caen announced his plan for continuing the advance toward Germany. He had concluded that 21 and 12 Army Groups should keep together and, as a solid entity, advance in such strength as to be “a force so strong that it need fear nothing.”

In his memoirs he stated in the plan’s Point 2 that “21 Group, on the western flank, [was] to clear the channel coast, the Pas de Calais, West Flanders, and secure Antwerp and South Holland.”

It should be noted that the plan did not specify that the Scheldt Estuary had to be cleared of water obstacles to free Antwerp’s port facilities as a major logistics node. That mission evidently would have been an implied part of his plan, but also by implication such responsibility would have been that of the Allied navy and not within his purview.

Also indicative of the ambiguous nature of the matter of opening the port, Montgomery, at this time the overall Allied ground force commander, went on to draw proposed boundary lines between the two army groups. Martin Blumenson, in Breakout and Pursuit, spelled them out: “Montgomery had drawn the boundary between army groups along a line from Mantes-Grassicourt to a point just east of Antwerp. The 21 Army Group thus had a zone that ended at the Scheldt—the Canadian and British armies at the conclusion of their advance would be facing the estuary.” It clearly appears that Montgomery did not intend that both the banks of the estuary were to be cleared, at least not by forces under his command.

Three days later, on August 20, at Eisenhower’s command post which had recently moved to the Continent, Ike held a strategy meeting that Montgomery did not attend. Instead, he sent his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Sir Francis W. “Freddie” de Guingand, with a set of notes, the first of which was, “The quickest way to win this war is for the great mass of the Allied armies to advance northwards, clear the coast as far as Antwerp, establish a powerful air force in Belgium, and advance into the Ruhr.”

There was no special emphasis on Antwerp, and Montgomery’s ultimate goal was in the northeast completely beyond the environs of the port city. As for Antwerp, it appears that Montgomery may have felt just getting to the city and not beyond it was sufficient for his immediate purposes.

Just securing the port facilities and not the waterway from the North Sea to Antwerp was of present concern. Did he anticipate that just ordering clearing “the coast as far as Antwerp” would automatically allow for the immediate use of the port facilities?

At the time Montgomery set forth his plan and announced his views on continuing the advance into Germany through his chief of staff, he was deeply involved in crushing the encircled German Seventh Army in the Falaise Pocket. Although he held strong views on how to proceed when the gap beyond Falaise was closed, he undoubtedly was more interested in accomplishing that mission than becoming involved in precise details of his projected plan of a further advance toward Germany.

Indeed, at the time of his announcing his views on future plans and Eisenhower’s meeting in August there was no indication that the Germans would soon be giving up eastern France and fleeing back to Germany. But Montgomery was soon to come to grips with the issue of how to proceed after the carnage in the German encirclement around and east of Falaise ended.

He claimed that on August 23, after the Poles and Americans had sealed the Falaise escape route, thereby trapping thousands of Germans who had not managed to get out in time, that he expressed to Eisenhower that Antwerp and the approaches to the port were a part of his request to receive a high priority in making the thrust on the Allies’ left flank.

But it also appears that Montgomery’s concern for capturing the port at the time was subordinate to his having “absolute” priority in his desire for an all-out concentrated advance northward toward the Rhine and Germany.

With his attempt to garner the majority of the means to support his plan, Montgomery now was also pushing for command of all the Allied ground forces; he wanted Eisenhower to relinquish such command and instead function as overall commander of air, land, and naval forces in operations in northwestern Europe. This point of contention served to distract such particulars as how to proceed in the face of swiftly collapsing German resistance.

Capturing the banks of the Scheldt Estuary and ensuring use of Antwerp’s port facilities was hardly within the scope of immediate operations and military politics over points of command. It soon, however, changed as the swift Allied advance brought the matter to the fore.

On August 27, Montgomery—who was just four days from handing over command of the ground battle to Eisenhower, a move he was decidedly against—issued orders for XXX Corps of General Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army to advance to the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary. The order, however, did not specify that once it was reached that the advance was to stop there. It was an order that appeared at the time to be ambitious but also realizable.

By August 30, the British Second Army had the Germans in full flight in front of it, and it was in the process of crossing the Seine River. The day before, the three armored divisions of the Second Army—the Guards Armoured, 7th, and 11th—had passed through the bridgeheads and were in full gallop northward.

On the 31st, the French city of Amiens was entered and a bridge over the Somme River was captured intact, thus expediting the advance. That day the commanding general of the German Seventh Army, General der Panzertruppen Heinrich Eberbach, and his tactical headquarters were captured, and the speed of Montgomery’s armor picked up momentum.

Early on September 3, the Guards Armoured Division crossed the Belgian border, and by nightfall it had captured the Belgian capital of Brussels, which was hastily evacuated by its German occupiers. The same day, the 11th Armoured Division had set off on Operation Sabot and, as noted, was in Antwerp early on the afternoon of September 4.

While the British Second Army pressed forward swiftly, on its left flank the Canadian First Army’s mission had more modest goals. On August 30 the Canadians entered the city of Rouen on the Seine River without opposition, but this was soon to change as they advanced.

In accordance with Hitler’s edict of not surrendering an inch of territory to the Allies, the Germans immediately to the front of First Army retreated into English Channel ports turned into fortresses to prevent their capture.

Enemy occupation of such fortress cities did not bode well for the Canadians trying to reach the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary. In fact, while the 11th Armoured Division was resting in Antwerp on September 4, the Canadian First Army was nowhere near its objective but was short of the Leopold Canal in Belgium. It was soon to engage in stiff fighting to get across that obstacle.

Still, on September 1, the port city of Dieppe was captured by the 2nd Canadian Division—the same unit that in August 1942 had suffered severe casualties in an abortive raid on that French port. Dieppe fell without resistance, and the Germans left without destroying the harbor facilities.

Two days later the Canadian II Corps was crossing the Somme River while the British I Corps under Canadian command was approaching the large Channel port city of Le Havre. The city, which now lay well behind the front lines, was, like the ports in Brittany—such as Brest and St. Nazaire—strongly fortified and manned by a garrison of 12,000 Germans.

In sum, with regard to the capture of Antwerp, Montgomery’s troops had only partially satisfied their mandate. The port facilities at Antwerp had been captured by Roberts’ 11th Armoured Division surprisingly without crippling destruction. On the other hand, the Canadians had not yet reached the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary. The mission of clearing the Scheldt and its banks to allow Antwerp to function as a logistics node appears not to have been a focus of Allied operations at the time.

That was to change, but not soon enough to improve the Allies’ critical supply situation, which was exacerbated by the failure to take timely measures in opening the port for operations.

Eisenhower was not entirely unaware of the complexity of opening Antwerp for supplying Allied troops. In logistics planning, the seizure of ports was critical to any success in defeating the Germans.

The Allied planners had expected that Cherbourg’s port facilities would be badly damaged. They had also hoped that the major port city of Brest in France’s province of Brittany would become available, but no one was under the illusion that the Germans would give that port up easily.

So it was with the other Brittany ports. A chance to seize Brest was lost when the U.S. 6th Armored Division stopped just short of entering the major port city in August. German paratroopers and other units were able to defend the city, and when it was finally captured after hard fighting in September, it was in ruins. It never did serve a significant logistics purpose.

Eisenhower did not take over ground command on the European continent from newly promoted Field Marshal Montgomery until September 1, but he was involved in planning well before. He was confronted with a situation that was not anticipated when the German opposition collapsed after the battle around Falaise ended.

His challenge was not only logistics, but dealing with Montgomery’s concept of assembling a massive force under his command and pushing north into the industrial Ruhr region of Germany.

On August 24, Eisenhower expressed anxiety about being able conduct desirable operations such as the two-pronged assault north and south of the Ardennes in Luxembourg directed at getting to the Rhine River and beyond. On that date none of the Brittany ports had yet been captured and, while fighting raged in Normandy before the breakout, supplies only had to be carried forward less than 20 miles; after August 24—as a result of the rapid advance of the Allied forces—supplies had to be carried forward 300 miles.

On September 4, when Antwerp was captured unscathed but unusable, Eisenhower was under different pressures that tended to divert any primary focus on the port. First, he had to deal with Montgomery, who felt he should be the commander of ground operations and who had already been advancing his plan for attacking the Germans and going on to win the war in Europe.

Second, there was a large contingent of airborne troops in Great Britain cooling their heels and waiting for a piece of the action on the Continent. Ground movement was so swift that potential targets for the use of airborne units were being quickly overrun. The Allied high command wanted to use this potent force and was eagerly looking for opportunities to do so. With the help of Montgomery, the opportunity was soon in hand. It was an operation called Market Garden.

The forward elements of 21 Army Group rested to the east from just north of Antwerp, while the group’s 1st Canadian Army sought to come abreast of the Second British Army in the west. Montgomery approached Eisenhower soon after September 4 with the idea of seizing a bridgehead over the lower Rhine River in Holland at the city of Arnhem with a swift, pencil-like thrust by an armored division linking up with three airborne divisions.

The parachute units would drop at vital points along a direct route to Arnhem, which would lead to the objective of gaining a bridgehead over the river at that city. The American 82nd and 101st and British 1st Airborne Divisions would pave the way for the British XXX Corps to capture a bridge in the vicinity of Arnhem. Montgomery’s Operation Market-Garden plan, with the enthusiastic support of the Allied high command, was approved by Eisenhower, who put it into effect.

The logistic implications for Market Garden, however, were great. As noted, the Antwerp port was not yet open, the supply lines reached back some 300 miles to the Normandy beaches, and the likelihood of the use of the English Channel ports was slim. The “logistical margin” was at best thin for the launching of the operation.

For example, three U.S. Army divisions were temporarily left in Normandy and divested of their trucks to provide enough vehicles to move the advancing Market Garden troops forward. Their trucks were employed to rush some 500 tons of supplies a day to the British conducting the deep thrust.

Transport aircraft, which were being utilized in large numbers to deliver supplies to Bradley’s 12th Army Group’s Third Army (Patton) racing across France had to be diverted to carry the airborne troops into battle and supply them until the ground link-up was made.

After Market Garden failed to meet Allied expectations, Eisenhower finally had to turn his major attention back to logistical matters. An important question arose as to how to resolve the port situation—specifically, how to open Antwerp to the North Sea. After Antwerp was seized and Market Garden failed to gain the way over the Rhine, there was a great deal of discussion as to what course of action was now to be taken. It was obvious, however, there was not going to be a speedy entry via Holland into the German Ruhr.

The key to success in opening the Antwerp port in the narrow time window was the British getting across the Albert Canal and advancing west to seize German positions on the north bank of the Scheldt Estuary. The situation at that time all along the front was in great flux, with each key element influencing the situation in a different way.

The Germans had received a wake-up call with the British capture of Antwerp. Thus they moved swiftly to remedy the confusion that followed. The evacuation of the bulk of German troops from the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary had just begun, and there were some 80,000 German soldiers between the Canadians and the Scheldt. The defenses along the Scheldt, however, being oriented toward the sea, had yet to be fully completed or manned, especially along the north banks.

Field Marshal Model, still commanding Army Group B on September 4, had few troops other than heavy coast artillery guns on Walcheren Island at the mouth of the Scheldt Estuary and antiaircraft artillery emplaced along the Scheldt’s northern banks.

Concern at the time, however, seemed to be more directed at filling the void in German lines created by the swift advance of Montgomery’s and American Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley’s army groups toward Germany than toward a threat to the water approaches to Antwerp from the sea or the Allies crossing the Scheldt. But time was on the Germans’ side.

For the Canadian First Army during this period, the south bank of the Scheldt, where Montgomery had delineated an objective, was “a bank too far.” The Canadians encountered more resistance in the form of German Fifteenth Army troops the farther north they struck and could not keep up with the British Second Army to their east. On September 4, advance Canadian elements were even short of the Leopold Canal, which had to be crossed before the Scheldt could be encountered.

The Americans wanted use of the port of Antwerp, but their interests at the moment rested elsewhere. Although Bradley’s First Army was advancing steadily, his Third Army was stuck on the Moselle River around Nancy and Metz in France.

Logistics was of major concern, but the competition for resources between Patton and Montgomery hobbled Third Army’s efforts to reduce the fortress city of Metz and advance into the German Saar. The beaches—and to a limited extent Cherbourg—and a few minor French Channel ports far from the combat had to be relied on for logistic support. At the time, Antwerp, when captured, was to be primarily used by the British.

Montgomery’s armies were focused on getting to the Rhine, not exploiting the capture of Antwerp. The swift advance to Antwerp left its captors gasping for breath. The 11th Armoured Division’s 100-mile rampage ending on September 4 at Antwerp’s docks left a confused but still active enemy to its rear, which was susceptible to delaying supply convoys.

Yet, as the window of opportunity closed, an attempt to exploit beyond Antwerp to the west was not made. Instead, Montgomery and the airborne high command struck toward the Rhine in Holland with Operation Market Garden.

Only with a stalemated situation existing after the conclusion of the failed attempt to capture the bridge at Arnhem was British attention directed to defeating the German Fifteenth Army holding the banks of the Scheldt Estuary. Instead of a massive invasion of Germany, the first priority became freeing the port facilities at Antwerp for operation. There was considerable debate between Eisenhower and Montgomery as to what priority should have been given to making Antwerp a viable logistics node. It was now clear that, after the failure of Market Garden, the bottom line for success was that all future operations in northwestern Europe would depend on using the huge capacity of Antwerp’s port facilities.

The Germans knew what to do in that narrow time window, and they did it. Zangen skillfully managed his evacuation from the south shore of the Scheldt. The British knew what to do, but they did not. Maj. Gen. Roberts later admitted he still had a day’s supplies remaining, and his 11th Armoured Division could have advanced north a further 18 miles to cut off the German escape route on North Beveland.

Opening Antwerp’s port was eventually accomplished, but not easily, and it required a great deal of time. Ships did not start unloading at the Antwerp docks until the end of November 1944—shortly before the Germans launched their “Battle of the Bulge” counteroffensive, the ultimate objective of which was to recapture Antwerp and drive a wedge between the British and Americans.

On October 8, Montgomery wrote that he was going to stop operations toward the Ruhr and concentrate on opening the approaches to Antwerp. He also noted, “Some have argued that I ignored Eisenhower’s orders to give priority to opening up the port of Antwerp, and that I should not have attempted the Arnhem operation until this had been done. This is not true. There were no such orders about Antwerp, and Eisenhower had agreed on Arnhem. Indeed, up to the 8th October 1944, inclusive my orders were to gain the line of the Rhine ‘as quickly as possible.’ On the 9th October, Antwerp was given priority for the first time—as will be seen from orders quoted above.”

It took the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division until October 22 to clear the south bank of the Scheldt Estuary after crossing the Leopold Canal using the British Buffalos––the American Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVT). During the same time the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division, trying to attack across the South Beveland isthmus, was stopped short of its objective. The British 52nd Lowland Division then was landed at Baarland on the south shore of South Beveland almost unopposed. It took until the end of October before the entire isthmus was in Allied hands.

To completely clear the banks of the Scheldt required the taking of Walcheren Island, which was largely flooded and heavily fortified. It took the British 4 Commando Brigade on November 1 to cross the Scheldt to Walcheren by landing craft and land at Westkapelle with 41 Commando (an infantry battalion equivalent) being ferried across to Flushing and followed by the British 155th Infantry Brigade to tackle tough German resistance.

After capturing the town of Middleburg on Walcheren, a linkup was made with Canadian troops advancing across the land bridge from South Beveland, and by November 8 Walcheren Island was in Allied hands. Now clearing the channel for sea-going vessels to reach Antwerp could begin. (See WWII Quarterly, Winter 2016.)

In the U.S. Army’s Logistical Support of the Armies,Volume II, the author noted, “Clearing the mines from the [Scheldt] proved a time-consuming task, and was not completed until 26 November. At that time much still remained to be done in the port itself, but of the 242 berths in the port 219 were completely cleared, all of the 600 cranes were in operating order, and all bridges needed for operations had been repaired.”

Coincidently, the port and Antwerp itself became the target for a series of murderous attacks by German “vengeance” aerial weapons. In one particularly horrendous incident, a V2 rocket hit the Rex Cinema on December 16, 1944, killing 567 people, 296 of whom were American, British, and Canadian service personnel. But in spite of the bombardment, port operations went ahead full steam.

Major General “Pip” Roberts, following his instructions, was concentrated on the capture of Antwerp’s docks; he did not try to seize the bridges over the Albert Canal north of the city with further advance in mind.

The 11th Armoured Division history states, “Had any indication been given that further north had been envisioned, these might have been seized within a few hours of our entry into the city.” But the division did not envision that it would need to advance farther north to cut off the German retreat from Walcheren Island and clear the north bank of the Scheldt Estuary.

Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, XXX Corps commander, had been instructed “not to advance any further than Antwerp for the moment, until supplies caught up—his orders were to ‘refit, refuel, and rest.”

In his memoirs, Horrocks stated, “My excuse is that my eyes were fixed entirely on the Rhine and everything else seemed of subsidiary importance. It never entered my head that the [Scheldt] would be mined and that we would not be able to use Antwerp until the channel had been swept and the Germans cleared from the coastlines on either side.”

Further, Horrocks admitted his troops could have advanced still farther north upon arriving in Antwerp and that his vehicles still had a hundred miles of fuel remaining in them and they had a day’s supply “within reach.”

Montgomery’s primary focus was on the major thrust into Germany, but he recognized that capturing Antwerp and putting the port into operation was the key to a sustained drive. Nevertheless, he chose to subordinate operations clearing the Scheldt while concentrating on his major plan.

In The Memoirs of Montgomery of Alamein, he wrote, “And here I must admit a bad mistake on my part— underestimated the difficulties of opening up the approaches to Antwerp so that we could get the free use of that port. I reckoned that the Canadian Army could do it while we were going for the Ruhr.”

Thus he had his excuse for not sending troops such as the 11th Armoured Division during the narrow time window to seize the north banks of the Scheldt and cut off the German retreat through Walcheren Island when he had a chance to do so.

Eisenhower had his own excuse. In his Report by The Supreme Commander to the CCofS on the Operation in Europe, he reasoned with regard to Antwerp and Market Garden, “My decision to concentrate our efforts in this [Market Garden] attempt to thrust into the heart of Germany before the enemy could consolidate his defenses along the Rhine had resulted in a delay in opening Antwerp and in making the port available as our main supply base. I took full responsibility for this, and I believe that the possible and actual results warranted the calculated risk involved.”

Thus he implicitly recognized that he had made a mistake by not insisting that the Scheldt Estuary be cleared and the port of Antwerp be made operational as a top priority before advancing farther northward. Ultimate results showed that it took almost three months before Antwerp became the principal Allied port for logistic purposes. The war in Europe lasted another eight months.

While the failure to open Antwerp for port operations promptly was one of the biggest mistakes from the Allies’ top command to division level—if not the biggest in the war in northwestern Europe—it still begs the question: could the Allies have won the war earlier if Antwerp had been available at the end of September rather than at the end of November?

Market Garden, Montgomery’s plan supported by the Allied high command to reach for the Ruhr and agreed to by Eisenhower, may not have been needed if priorities had been different, but with the failure to use that narrow September 4-6 time window the question is moot.

In any case, it appears that the basic military maxim of exploiting success when the opportunity presented itself—in this case in a short time window—was violated. That perhaps was the greatest mistake made by Eisenhower and Montgomery. Unfortunately, thousands more on both sides died because of the delay in ending the war.

No maps?

You might find the map in this related story helpful:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-hardest-fight/