By Michael D. Hull

Of the many highly successful fighter planes and bombers in the Allied arsenal during World War II, none was more versatile or singular than the Royal Air Force’s de Havilland Mosquito.

Constructed of spruce, birch, balsa, and plywood, the twin-engine, two-seater “Wooden Wonder” played a unique role in 1941-1945 as a bomber, U-boat hunter, night fighter, strafer, pathfinder, interceptor, and reconnaissance plane. It was the first true multi-role aircraft, with almost 50 variants built. Fast and deadly, Mosquitos flew in several theaters of operation, including Europe, the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, and the Far East.

Some aviation experts have rated the Mosquito as the outstanding British airplane of the war, ahead of the legendary Supermarine Spitfire, the workhorse Hawker Hurricane, and the formidable Avro Lancaster.

“The Mosquito helped transform the fortunes of the bomber offensive,” said historian Max Hastings. “It was obvious that this was a real game-changer. In many ways, from the outset it became plain that the Mosquito was a much more remarkable aircraft than the Lancaster. Yes, the Lancaster is the aircraft that everybody identifies with Bomber Command, but in many ways, the Mosquito, although it has received much less attention, was a much more remarkable aircraft…. I think some of us would argue this is a more remarkable design achievement than the Spitfire.”

Eric “Winkle” Brown, a wartime test pilot, agreed: “I’m often asked what type of aircraft saved Britain. My answer is that the Mosquito was particularly important because it wasn’t just a fighter or a bomber. It was a night fighter, a reconnaissance aircraft, a ground-attack aircraft. It was a multipurpose aircraft.”

The German Air Force had nothing equal to the Mosquito, except the Heinkel 219 Uhu (Owl) night fighter, which made its debut in June 1943. Encounters with the “Mossie” shook the morale of Luftwaffe aircrews, and they were permitted to claim two kills for each Mosquito they were able to shoot down. Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, the boisterous, rotund Luftwaffe chief, admitted that the RAF fighter bomber made him “green and yellow with envy.”

Like such famous warplanes as the Spitfire, Hurricane, B-17 Flying Fortress, P-40 Warhawk, and B-25 Mitchell, the concept of the Mosquito originated in peacetime. After taking over the reins of RAF Bomber Command in September 1937, sharp-eyed Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar R. Ludlow-Hewitt strove tirelessly to upgrade preparedness as tensions mounted across Europe. In a March 1939 report he said that he had spent 18 months pressing unsuccessfully for what he called a “speed bomber.” He believed there was an urgent need for such a plane to undertake photographic reconnaissance and harassment bombing.

As it happened, a similar plan had been proposed and acted upon by aviation pioneer Geoffrey de Havilland, a clergyman’s son and cousin of Hollywood star Olivia de Havilland. At his aircraft factory near London, work was started on a wooden airplane that would carry no armaments and rely on its two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines for protection. Its speed would enable it to evade all other fighter planes. Design work began late in 1938 at Salisbury Hall, a few miles from the company headquarters in Hatfield, Hertfordshire. The idea of an all-wooden aircraft ran counter to modern design trends, however.

The Air Ministry wanted only conventional, heavily armed, all-metal aircraft. Unimpressed with de Havilland’s plane, it regarded the proposal as wholly retrogressive and filed it in a “pending” tray. When war with Germany was declared on September 3, 1939, two days after the invasion of Poland, de Havilland saw no reason to modify his proposal, and, likewise, the ministry saw no reason to accept it.

But de Havilland found two powerful allies. One was Air Chief Marshal Sir Wilfred Freeman, “father” of the British heavy bomber force and member of the Air Council, and the other was Patrick Hennessy of Ford Motors, who had been brought in by Lord William Beaverbrook to help run aircraft production. Thanks to Freeman, de Havilland and his staff were instructed to commence designing a light bomber that could carry a 1,000-pound bomb load to a distance of 1,500 miles.

Work on “Freeman’s Folly” began in late December 1939, and wood was used for its structure in order to conserve light alloy and other vital metals. Skilled and semiskilled carpenters, joiners, and cabinetmakers from furniture manufacturers around the country were recruited to build the planes.

The project was confirmed by an Air Ministry specification on March 1, 1940, resulting in an order for 50 aircraft. De Havilland’s work was temporarily postponed, however, by the British defense crisis following the Dunkirk evacuation, the threat of a German invasion, and the RAF’s desperate need for more in-production fighters and bombers. Eventually, after the Battle of Britain waned, the Mosquito program was reinstated.

With balding Captain Geoffrey de Havilland Jr., chief test pilot, at the controls, a Mosquito Mark I prototype made its maiden flight on November 25, 1940, at Hatfield. The plane flew like a pedigree, and, once minor problems were eliminated, factory testing proved that this would be an outstanding aircraft, exceeding the performance margins of its specification. Skeptical military and government officials were astounded when the plane was demonstrated for them.

The Mark I had a 54-foot wingspan, the maneuverability of a fighter, a cruising speed of 325 miles per hour, a maximum speed of 425 miles per hour, a service ceiling of 33,000 feet, and a range (with bomb load) of 1,650 miles. The officials were staggered to see the Mark I perform smooth climbing rolls on one engine, with the second engine “feathered” to prevent windmilling and cut drag to a minimum. Any lingering doubts about De Havilland’s new plane were swept away.

Official Mosquito trials began at Boscombe Down on February 19, 1941, and three prototypes were built in secrecy at the De Havilland plant in Hertfordshire. Nine designers worked on the project, and priority production was started that July. The Mosquito entered production in less than two years after the design stage—a remarkable aviation achievement. The last of the prototypes to fly, on June 10, was a photo-reconnaissance version. The promised combination of high speed and altitude fitted the plane ideally for such a role.

An initial daylight reconnaissance sortie over the French ports of Brest, La Pallice, and Bordeaux was made by a lone Mosquito Mark I on September 20, 1941, and it confirmed the concept of high speed and initial lack of armament. The Mark I easily outpaced three Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters that attempted to intercept it.

The next Mosquito type brought into service was the Mark IV, which could carry four 500-pound bombs and was intended to replace the Bristol Blenheim, a much slower workhorse light bomber that had been operational for four years. Deliveries to the RAF’s No. 2 Group began in November 1941, and the Mark IVs were assigned to No. 105 Squadron based at Swanton Morley in Norfolk. The next batch of planes was delivered to No. 139 Squadron at Marham, Norfolk.

The pioneering squadrons’ pilots and ground crews spent the winter of 1941-1942 getting used to the Mosquitos and learning how best to deploy them in combat. The pilot and navigator sat side by side, working as a close-knit team, and the crews loved the new plane.

It was soon apparent that the Mosquito had an enormous capacity to absorb damage and that its structure was easy to repair. Mounted in a mid-position, the cantilever wing was a one-piece assembly, with plywood used for the spar webs and all skins. The fuselage consisted of a plywood-balsa-plywood sandwich and was constructed in two halves.

The leaders of No. 2 Group were eager to deploy their wooden wonders at the earliest opportunity, so operations got underway in late May 1942. Armed with bombs and cameras, four Mosquitos of No. 105 Squadron took off on May 31 to “harass and obtain photographic evidence” of the RAF’s first 1,000-bomber raid on Cologne the previous night. The German air defenses were intense, but the Mosquitos had little difficulty avoiding Luftwaffe fighters. This was the Mosquito bombers’ first operational sortie.

The Mark IVs of No. 139 Squadron received their baptism of fire on June 25-26 when they made a low-level raid on the airfield at Stade near Wilhelmshaven. On July 1-2, 1942, the squadron bombed the submarine pens at Flensburg in the first mass low-level strike by Mosquitos. A series of high-level “siren raids” at night followed that month, as No. 105 and 139 Squadrons ranged far and wide across Germany. The aim was to deprive factory workers of sleep and to disrupt war production.

Roaming all over Nazi-occupied northern Europe, and even as far as Malta, the Mosquito squadrons continued to harass enemy bases, airfields, roads and rail lines, ports, and shipping with long-range “nuisance raids.” Hit-and-run tactics were perfected, and the wooden wonders proved unsurpassed as low-level day and night raiders. On September 19, 1942, six of the planes made the first Mosquito daylight raid over Berlin.

Six days later, on September 25, four Mosquitos of No. 105 Squadron made the most daring mission yet attempted and the first such raid to be reported to the British public. After a lengthy flight northeastward across the North Sea, four Mosquitos flew at rooftop level to attack the Gestapo headquarters in Oslo. Their objective was to destroy Norwegian Resistance records being kept in the building, to disrupt a rally of Nazi sympathizers, and to give a demonstration of Allied air power.

The headquarters was not damaged, but surrounding buildings were hit and four people killed. One of the bombs failed to explode in the Gestapo building, three others went through its far wall before detonating, and a Mosquito was shot down by Focke-Wulf FW-190 fighters, but the raid was later termed “highly successful.” It panicked the Nazis and their Quisling allies. Many fled from the city, and their rally ended in chaos while Norwegian patriots cheered.

Involving a round trip of about 1,100 miles and an air time of four hours and 45 minutes, the Oslo raid was the first long-distance mission flown by Mosquitos. Armed with 20mm cannons, rockets, and machine guns as well as bombs, Mosquitos later attacked Gestapo headquarters buildings in The Hague and Copenhagen.

Reichsmarshal Göring boasted often that no enemy airplane could fly unscathed over Berlin, but he received a rude awakening on the morning of January 31, 1943, when No. 105 Squadron became the first full Mosquito unit to attack the German capital. The planes successfully scattered a parade that was to be addressed by the Luftwaffe chief. That afternoon, planes from No. 139 Squadron zoomed in at low level to disrupt a Berlin parade waiting to be brainwashed by Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels. The deadly and elusive Mosquitos were fast becoming an embarrassment to the Germans.

On one occasion, Mosquitos raided the Berlin radio station where Göring was about to broadcast a speech. He was delayed for an hour and was not amused. “The British, who can afford aluminum better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased again,” he declared angrily. “What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses, and we have the nincompoops.”

The first Mosquito squadrons, Nos. 105 and 139, carried out their final large-scale daylight raid on May 27, 1943, and then took on more hazardous assignments. The following month they were transferred to RAF Bomber Command’s No. 8 Pathfinder Group, led by hard-driving Air Commodore Donald C.T. Bennett. The Mosquitos led the way and marked targets for the main forces of Bomber Command’s heavy Stirlings, Lancasters, and Halifaxes as they made punishing nightly raids on German cities and industrial centers.

Mosquitos were built in Australia and Canada, as well as Britain, and more squadrons were formed for a variety of day and night missions—low-level bombing and strafing, escort, shipping strikes, night fighting, and photo- and weather reconnaissance. The plane proved particularly successful as a light precision bomber and as a radar-equipped night fighter.

From early 1944 until VE-Day, the U.S. Eighth Air Force operated the second largest fleet of Mosquitos (more than 120) for reconnaissance duties. Many marks of Mosquitos flew under other Allied colors, including the red star of the Soviet Air Force.

Mark IV, IX, and XVI Mosquitos of the RAF and the Commonwealth air forces saw considerable service in the Middle East, while others were eventually deployed to the Far East after initial problems with the effects of tropical conditions on their wooden structure were overcome.

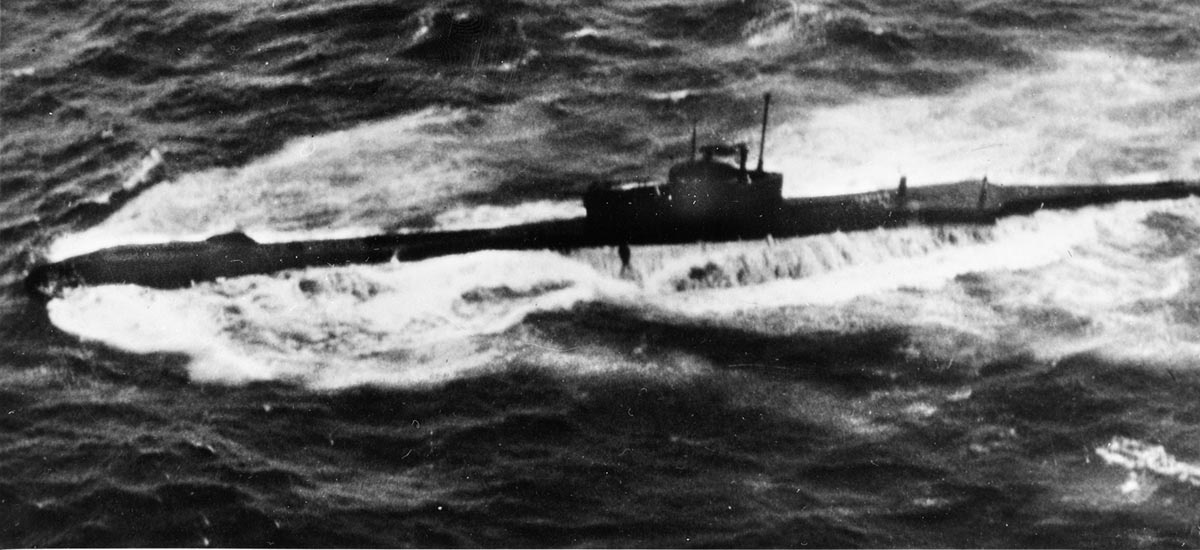

As the war progressed and the Allies began to gain the upper hand over the Axis powers, Mosquitos were in the forefront and performing a mounting variety of missions. While RAF Coastal Command Sea Mosquitos were going after U-boats in the Atlantic, other squadrons were photographing and harassing German shipping in the North Sea and around Norway; sinking enemy vessels in Bordeaux and other French ports; guiding and escorting RAF Lancasters on their nightly raids; dropping 4,000-pound “cookie” bombs on Germany; identifying enemy flying-bomb sites on the Baltic coast and elsewhere; and gathering vital photo-intelligence on German defenses and installations along the northern French coast before the 1944 Allied invasion.

Besides destroying important targets on the European continent, Mosquito fighter bombers scored hundreds of kills in aerial combat. And, like the 1942 raid on the Gestapo headquarters in Oslo, the wooden wonders continued to undertake daring precision assaults on specially assigned targets that garnered homefront headlines and cemented the Mosquito’s reputation as a legendary airplane. The most spectacular of such raids was made on Friday, February 18, 1944.

British intelligence had learned that a number of important French Resistance workers were being held by the Nazis and facing execution at the prison in the historic city of Amiens, 72 miles north of Paris. The captives were needed by the Allies to implement sabotage plans once the scheduled Normandy landings had taken place, so it was decided to try and free them. Operation Jericho, a daylight precision raid, was hastily planned under the command of RAF Group Captain P.C. Pickard, a winner of the Distinguished Service Order with two bars and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Eighteen crews from British, New Zealand, and Australian Mosquito squadrons were hand picked for one of the boldest, most complex aerial operations of the war. They were to blast the prison walls in two places so that the prisoners could get out, destroy the wing where German guards were housed, and blow open the ends of the main building, but with as little force as possible in order not to harm the captives. Pickard told his crews, “It’s a death-or-glory show, boys. If it succeeds, it will be one of the most worthwhile ‘ops’ of the war. If you never do anything else, you can still count this as the finest job you have ever done.”

The weather on February 18 was vile, with rain, snow, and high winds, and any other operation would have been scrubbed. But the lives of more than a hundred Frenchmen, who might face firing squads at any moment, depended on the RAF. So a start had to be made.

Pickard and his Mosquitos took off, swept across the English Channel at low level, and blasted the prison on schedule. Out of 1,000 inmates, about 180 of whom were prisoners of the Nazis, 87 were killed but more than 250 escaped. They included Raymond Vivant, a key Resistance leader, and 12 of his comrades who were about to be executed. The raid was a spectacular success, although the gallant Pickard lost his life, and the Air Ministry hailed it as “one of the most memorable achievements of the Royal Air Force.”

By day and night, there was little respite for the Mosquito squadrons in the last year of the war, and they distinguished themselves when the Germans launched more than 7,000 V-1 and V-2 rockets against London and southeastern England from June 1944 to March 1945. The flying bombs, nicknamed “doodlebugs,” killed 8,041 people, injured 23,925, and destroyed 23,000 houses.

Along with antiaircraft batteries, Spitfires, Hawker Tempests, P-51 Mustangs, and Gloster Meteor jets, the Mosquitos played a key role in pursuing, intercepting, and downing the Nazi missiles. The Mosquito night fighters were particularly busy because the majority of rocket launchings took place after the fall of darkness. Two squadrons, Nos. 96 and 418, shot down 264 flying bombs, and Mosquitos caught and destroyed a total of 600 V-1 rockets.

Modified and equipped with bombs, rockets, and 57mm cannons, the wooden wonders also made many sorties against rocket bases in France and Holland, factories, roads, railways, and German shipping while continuing to scourge the Luftwaffe. By November 1944, Mosquito crews had shot down 659 enemy planes. They scored 600 victories over Germany alone. Much feared by the German Air Force, they turned Göring’s night fighters from hunters into the hunted.

While wreaking havoc on the Luftwaffe, Mosquito squadrons kept up the pressure on Gestapo installations at several continental locations, including France, Holland, and Denmark, to support the Resistance movements. They destroyed the Dutch central population registry in The Hague in April 1944, attacked the Gestapo headquarters there, and made two “surgical” raids—one with brilliant and one with mixed results—in Denmark.

On October 31, 1944, three squadrons of RAF Mosquito fighter bombers carried out a low-level attack on a line of terrace houses, forming part of the university in the historic seaport of Aarhus on the eastern coast. Picking out individual houses in the row, the planes burned up all of the Gestapo files and killed more than 150 German officers in a conference.

On March 21, 1945, a smaller force of 18 Mosquitos flew to Denmark on a more difficult mission. Zooming in at rooftop level, the raiders attacked the Shell Oil Co. offices in central Copenhagen, a six-floor block with prisoners on the top floor and Gestapo offices and files in the rest. Twenty-seven prisoners escaped, including two members of the Danish Freedom Council, but six were killed. More than a hundred Germans and collaborators were killed, but all of the senior staffers were away at a colleague’s funeral.

One of the Mosquitos in the first wave flew in so low that it hit a tall pylon, swerved, and crashed into a school. Its bombs exploded. Several following planes bombed the school by mistake, killing 17 adults and 86 children. But Danish Resistance members were pleased on the whole with the raid. They welcomed back their freed comrades, looted some arms from the wrecked building, and confiscated a file cabinet containing “V-Manner” information on collaborators, the basis for postwar treason trials.

Mosquito squadrons continued their numerous “nuisance raids,” pathfinding missions, reconnaissance sorties, and attacks on enemy U-boats and shipping until the European war reached a conclusion in the spring of 1945. Then they were called upon for new assignments—scattering leaflets over prisoner-of-war camps in Germany and guiding British and American heavy bombers dropping food bundles to the starving people of Nazi-occupied Holland.

A total of 7,781 Mosquitos were built—6,535 of them in Britain, 1,034 in Canada, and 212 in Australia. After the war, RAF Mosquitos flew against insurgents in Indonesia and Malaya and remained in operation until December 1955. They also were used by a number of postwar air forces, including those of France, Belgium, Denmark, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Sweden, Israel, Yugoslavia, South Africa, Turkey, China, and Dominica. Ten of the versatile wooden wonders were even used in civil service, ferrying high-priority passengers and cargo between Britain and Sweden for British Overseas Airways Corporation.

In the postwar years, the Mosquito’s unique wood-plywood-glue construction became its biggest weakness. While metal-framed aircraft endured, with many restored World War II types still flying, most Mosquitos simply rotted away in their hangars. After the last one crashed during an air show near Manchester, Lancashire, in 1996, killing both crewmen, there were no more airworthy Mosquitoes.

It was left to Jerry Yagen, an American aviation enthusiast, to remedy this situation. Over eight years and at great cost he meticulously restored a Mosquito. It was flown by Worcestershire-born Arthur Williams, a disabled former Royal Marine, who was the presenter of a British television documentary, The Plane That Saved Britain,which aired in the summer of 2013.

Author Michael D. Hull has written on many topics for WWII History. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Excellent article. Very informative, thank you!