By Alex Zakrzewski

After five hours of continuous slaughter, an eerie calm descended on the blood-soaked plain near the Roman city of Adrianople. As far as the eye could see were bodies, some of which were piled high in gruesome mounds. The fighting had been so savage and cramped that men fought and died atop the bodies of their comrades. Compounding the carnage was the heat. August 9, AD 378, had been a brutally hot day. As the din of battle finally faded, all across the battlefield the wounded could be heard wailing for water as they slowly suffocated beneath the crushing weight of the dead. For them, the cooling dusk brought no relief.

With the battle finally over, the two sides took stock of what had occurred. While the victorious Goths offered prayers of thanks to their ancestors, the surviving Romans fled into the nearby woods and hills to contemplate the scale of their defeat. Fifteen thousand men lay dead or dying. The losses constituted more than two-thirds of the Roman Army. Among them were 35 tribunes, two senior officers, and the Eastern Roman Emperor himself. Valens’ body would never be found. Much like the myth of Roman invincibility, it was too badly mangled to recover.

In the days that followed, news of the calamity spread across the Roman world like a plague, bringing with it a similar sense of helplessness and impending doom. St. Ambrose went so far as to predict the end of humanity and the end of the world. Not since the days of Hannibal had Rome been so threatened. The Goths were poised to strike deep into the heart of the empire and it seemed only a matter of time before every other barbarian race along the frontier did the same. As citizens across the Empire braced themselves for the coming onslaught, there was one question on everyone’s lips: “How could this have happened?”

The Battle of Adrianople is a story of desperation, greed, incompetence, and envy that began years earlier north of the Danube River in the land the Romans called Barbaricum. This vast region between the Carpathian Mountains and the Crimea was dominated by the Goths, a Germanic people who had migrated south from the frozen shores of the Baltic centuries before. During the 3rd century, Romans and Goths had fought a series of brutal battles. But by the mid-4th century, the two sides had settled into a tense but mutually beneficial coexistence. Roman commerce and Christianity spread rapidly among the Gothic nobility. At the same time, the Imperial legions, decimated by years of civil war and population decline, had become heavily reliant on well-trained, well-armed Gothic mercenaries, many of whom served long terms of service across the Empire.

This tenuous peace was shattered in the 370s by the appearance on the fringes of Europe of a people that defined the world barbarian. Dressed in the rotting skins of field mice and nourished on raw meat they tenderized beneath their saddles, the ferocious Huns had blazed a trail of destruction across the Eurasian steppe before stumbling on the rich lands of the Goths. At first they seemed content to merely raid isolated Gothic settlements and even served the warring Gothic tribes as mercenaries. Eventually the Goths’ lands proved too tempting a prize and they outright invaded. In so doing, they also sparked an invasion from the Alans, another steppe people whom the Huns had displaced in their relentless drive across Central Asia.

The divided Gothic tribes stood no chance against this dual onslaught, and one by one they fell like dominoes. The survivors retreated westward into the lands of their kin, eventually fortifying themselves in the rough, forested slopes of the Carpathian Mountains. It was here that Fritigern, a chieftain of the Thervingi tribe, stepped forward to unite the refugees. Fritigern knew that they could not remain indefinitely in their mountain strongholds, and he somehow managed to convince his proud people that their only hope was to cross the Danube and seek sanctuary within the Roman Empire.

In the summer of AD 376, huge numbers of Gothic refugees began gathering on the northern banks of the Danube, a point that is now the modern Bulgarian city of Silistra. It was a desperate and disparate group that included Goths from all tribes and clans. The Romans had an excellent record of settling and assimilating barbarian tribes going back many centuries to Caesar’s conquest of Gaul; however, they were totally unprepared for the mass of humanity they were now confronted with. Roman historians put the number of refugees as high as 200,000, though a third of that number is a more realistic figure. Either way, it was an enormous number of people, even by modern standards, that would have to be disarmed, fed, housed, and settled on suitable land. Imperial border officials were quickly overwhelmed, and a delegation of Goths led by Fritigern was sent to negotiate directly with Eastern Roman Emperor Valens.

Valens was not in Constantinople but on the Armenian frontier campaigning against the Parthians when the crisis on the Danube arose, and it was many months before Fritigern reached him. Fritigern promised military service in exchange for land, and as a further show of goodwill, even converted to Valens’ Arian branch of Christianity. Impressed by this show of respect and always in need of more soldiers, Valens agreed to Fritigern’s terms. He even ordered the Roman border fleet on the Danube to help bring the refugees over.

It was many more months before Fritigern returned to the Balkans with the good news. During this time, the situation had worsened considerably. The food and supplies the Goths had brought with them had long been exhausted, and the Huns were beginning to drive toward the Danube. When Fritigern announced that he had struck a deal with the Romans, many Goths did not wait for the Imperial ships to arrive but instead waded into the swollen summer currents and drowned attempting to swim across. For weeks, the Danube teemed with rafts and crafts of all kinds as tens of thousands of men, women, and children of all ages poured across to what they believed would be their safe haven. They were sorely mistaken.

Valens ordered his border officials to provide the refugees with temporary food and shelter until they could be settled farther south in Roman Thrace; unfortunately, the two leading officials on the scene were Lupicinus, the local governor, and Maximus, the commander of the frontier troops. Even by the notoriously avaricious standards of Roman provincial officials, these two men stood out for their wanton greed, and they predictably saw in the desperate hordes of refugees an opportunity to line their own pockets. Instead of feeding the Goths, they sold them rotting food at inflated prices. When the Goths ran out of money, they were offered a pound of bread for every slave they handed over. When the slaves ran out, they bartered their children in exchange for dogs to eat.

The Goths were a proud people, and it was not long before disaffection began to spread. They could not understand why they were being made to starve instead being allowed to settle on land of their own, as was the agreement Fritigern had struck with the Romans. Eventually the deprivation and humiliation proved too much and they broke out of their riverside camps and began moving south toward the Roman city of Marcianople. Though the Goths were not yet in open revolt, the situation was rapidly spinning out of control, and Lupicinus and Maximus found themselves in a precarious position. The border garrisons were too small and thinly spread to corral the Goths back into their camps. They could hardly send to Constantinople for reinforcements without revealing their own wicked activities. The two schemers instead hatched a plot that would have dire consequences, both for themselves and the entire Empire.

As the Goths approached Marcianople, the Romans invited Fritigern and the Gothic leadership into the city to negotiate over a sumptuous banquet in the governor’s palace. The plan was to ply the barbarians with food, wine, and women until they were sufficiently distracted, then murder them all and cut any potential revolt off at the head. To reassure Fritigern that nothing was amiss, they allowed him to bring into the city a small armed escort of bodyguards that would remain outside the palace while he and his party feasted. They even spared the Gothic leaders the indignity of disarming before entering the banquet hall. To make sure their plans were not interfered with, a large detachment of the city’s garrison was posted outside the walls to keep an eye on the anxious refugees.

At first, everything went as planned. Then, just as the festivities were getting started, a commotion erupted outside the palace. It seems that the people of Marcianople had come to despise the hordes of Goths milling about their countryside, eating their crops and defiling their land, and they decided to vent their frustrations on Fritigern’s bodyguard. Sneers and jeers quickly led to fists and stones, and eventually weapons were drawn and a deadly brawl broke out. The clamor caused everyone inside the palace to panic and spring the trap prematurely. In the ensuing melee, all the Gothic leaders were killed except for the wily Fritigern, who managed to fight his way out and even steal a horse before escaping.

Outside the walls, the Goths heard the fighting inside the city and immediately realized that the Romans had once again double crossed them. Their patience finally snapped. If the Romans would not honor their agreement, then they would take what was owed to them. Though poorly armed, they attacked and slaughtered the Romans troops keeping watch over them and took their weapons. Fritigern returned to find the clan banners unfurled and the war horns blaring. Even if he wanted to, there was now no containing his peoples’ fury. The Gothic Revolt had begun.

The Goths did not have the means to take the city, so they instead swarmed the countryside, pillaging Roman farms and villas and butchering the inhabitants. Lupicinus scrambled together what troops he could and confronted the horde about nine miles west of Marcianople in a last-ditch effort to end the Gothic problem once and for all. In the short, fierce battle that followed, the outnumbered Romans were annihilated. Lupicinus was last seen galloping back to Marcianople having abandoned his troops, standards, and weapons to the enemy.

The Goths spent the following year rampaging unchecked across the Balkans. Thousands of Romans slaves, many of them Goths recently sold into bondage, rebelled against their masters and joined Fritigern’s growing horde. Many of these erstwhile slaves proved invaluable sources of local intelligence, readily pointing out hidden stores of food, horses, and weapons. The isolated Roman garrisons could only watch helplessly from their city walls as the countryside burned and the barbarians’ numbers swelled. Fritigern tried to take Adrianople but was repulsed due to a lack of siege weapons. Still, the Goths scored a victory of sorts when a large garrison of Roman troops of Gothic origin mutinied en masse and marched out to join the invaders.

By that point Valens had noticed the escalating emergency in the Balkans and transferred some of his veteran units from the east under the command of his trusted generals, Trajan and Profuturus. He also asked for reinforcements from his nephew, Western Roman Emperor Gratian. The western emperor duly dispatched the aging but experienced General Frigeridus and the commander of his household troops, Richomeres, to the east with a large force drawn from his Gallic Field Army. Unfortunately, Gratian was dealing with his own border troubles and the troops he sent were largely second-rate auxiliaries. A great many deserted before even leaving for the Balkans.

Trajan and Profuturus originally sought to bottle the Goths up in the Balkan Mountains where starvation and the elements would do the fighting for them. It was a shrewd strategy but it was poorly executed, and in the summer of AD 377 a large force of Goths led by Fritigern managed to evade the blockaders and move north out of the mountains, back towards the Danube. Trajan and Profuturus pursued them and en route linked up with Frigeridus and Richomeres. The latter took command of the combined Roman force and followed the Goths to a fertile meadow near the mouth of a river called Ad Salices or “Place by the Willows.” Like Lupicinus, he hoped to quash the Gothic revolt in one decisive encounter.

The Goths were well informed of the Romans’ movements, and as they waited for them to arrive, they fortified themselves in a carrago, a type of wagon laager common to the peoples of the Eurasian Steppe. They also sent out calls for help to other scattered parties of Goths along the Danube. Their calls were answered, and by the time the Romans arrived to do battle their numbers had grown considerably. The exact number of Gothic warriors is unknown, but there were more than the 12,000 men the Romans had. Most would have been infantry armed with a combination of captured Roman arms and traditional Gothic weapons like battle axes and huge war clubs with fire-hardened points.

The exact date of the Battle of Ad Salices is unfortunately lost to history, but it was most likely sometime during the late summer of AD 377. The two armies met shortly after dawn. Fritigern moved first, occupying a section of high ground that gave him a commanding view of the enemy movements. Having taken their positions, the two sides advanced cautiously toward one another, shoulder to shoulder, shields overlapping. Just as it looked like the front lines were about to meet, they halted and stared at each other like two heavyweight prize fighters sizing each other up before a match. The legionnaires broke the silence by sounding their barritus war cry, an ironically Germanic chant that began with a low rumble that swelled to a deafening roar. The Goths responded in their own traditional way by blowing war horns and yelling the names of their ancestors. Amid this cacophony of voices and instruments, the orders to attack were given, and the two sides crashed into each other.

For most of the day the two shield walls jostled back and forth, the Goths smashing heads with their hammers and clubs, the Romans hamstringing legs with their swords. At a certain point, a fierce Gothic charge broke the Roman left. But Richomeres committed his reserves and the line was quickly restored. The opponents disengaged at dusk. Both commanders sent their cavalry in to run down any stragglers. Both sides were utterly exhausted and badly bloodied by the day’s hard fighting. The Romans, in particular, suffered greatly because they had fewer men than the Goths. Richomeres spent a week laying siege to the Gothic wagon fort, but his losses were such that he could no longer seriously challenge Fritigern and the Romans marched back south.

Valens was furious when he heard that Ad Salices had not been a decisive victory. He sacked Trajan and replaced him with Sebastian, a decorated general with years of campaigning experience on both the western and eastern frontiers. The reason that Richomeres was not blamed remains a mystery. Perhaps it was because he returned to the west immediately after the battle to cajole more troops out of Gratian. Sebastian enacted a divide and conquer strategy that involved once again blockading as many Goths as possible in the Balkan Mountains while still keeping a watchful eye on Fritigern and his band along the Danube. Sebastian’s tactics proved extremely effective and soon the Goths trapped in the mountains were growing increasingly desperate. But just when it seemed that their luck had run out, Fritigern did the unthinkable and struck a deal with the same Huns and Alans that had driven the Goths out of their homeland.

The Huns and Alans, lured by promises of booty, poured into Roman territory and rapidly overwhelmed the thinly spread Roman troops guarding the mountain passes. Sebastian was forced to abandon his divide and conquer methods and consolidate his forces in the towns and cities, leaving the barbarians the run of the countryside. After the drubbing at Ad Salices the Romans were anxious to avoid another pitched battle and they instead fought a hit-and-run campaign with the invaders in a desperate effort to buy time until reinforcements arrived. When at Diabaltum a column of elite Roman infantry was ambushed and destroyed almost to a man by a force of Gothic cavalry, Roman morale sank completely. As the year came to an end, the Imperial commanders concluded that only a major joint expedition by both the eastern and western Imperial armies could defeat the Goths.

In the spring of AD 378, Valens made a hasty peace with the Persians and returned to Constantinople to plan the campaign against the Goths. He found his citizens in a violent uproar. The people were furious about the situation in the Balkans and they blamed their emperor for letting it get so out of hand. Valens took their vitriol personally. He was not a bad emperor. Actually, he had governed the east admirably well for more than a decade. But he had never been loved by his people and he resented them for it. Part of his unpopularity was due to his Arian Christian faith, which set him apart from the Catholic majority. Nevertheless, Valens also was by all accounts a boorish, cruel, and vindictive man. His bowlegged, potbellied frame and squinting, curmudgeonly demeanor matched his personality and inspired more snickers and jokes than confidence or loyalty.

The anger in the capital also fueled Valens’ growing envy and distrust of his nephew Gratian. The western emperor, even though he was just 19 years old, already possessed all of the good attributes that his uncle lacked. He was handsome, endearing, and sophisticated. Everyone loved him. Worse yet, while the Goths had been making fools of Valens’ generals in the Balkans, in the West, Gratian had led his legions to glorious victories against the barbarian tribes of the Rhine frontier. Stories of his bravery and ingenuity in battle were the talk of the Empire. Valens, who had deeply resented having to ask his nephew for troops the year before, was stung by this news and loathed having to work with him in the coming campaign. He had no illusions as to who would get the glory in the event of a major victory over the Goths.

The mood in Constantinople was so volatile that after only 10 days Valens moved his headquarters to the Imperial estate of Melanthias, about 12 miles west of the capital. Here he consolidated his forces and planned his next moves with his commanders. To ensure his troops’ loyalty after their exposure to so much dissent in the capital, he prudently saw to it that they were paid and well supplied. He also ordered Sebastian, his most successful commander, to take a picked force of 2,000 men and distract the Goths by waging a guerrilla campaign against some of the smaller war bands.

For the next few months, the advantage seemed to shift back to the Romans. The Goths and their allies were dispersed along the fertile river valleys of the Eastern Balkans, mostly between Marcianople in the north and Adrianople in the south. Sebastian’s hit-and-run tactics proved surprisingly successful in ambushing and destroying unwary raiding parties. At the same time in the Western Balkans, Frigeridus succeeded in blocking the westward mountain passes, effectively trapping the barbarians where they were. In June, more good news arrived, this time from Gratian. He had finally restored order to the Rhine and was sailing down the Danube with an army of his own. Encouraged by these fortuitous events, in July Valens marched north to Adrianople to link up with his nephew.

Fritigern noticed the Roman noose tightening and he too began calling together the scattered war bands and consolidating them into a single fighting force. When he learned that Valens had arrived at Adrianople and was showing no signs of moving any farther, he marched south toward the town of Nice, about 16 miles southeast of Adrianople. It was a sound plan. Taking the town would cut the Romans off from the capital, severing their main supply line and forcing Valens into either a risky battle or out of the Eastern Balkans entirely.

When Valens heard of the Goths’ moves his patience, never one of his strongest virtues, began to run out. Richomeres had returned from the west with news that Gratian had run into a sizable force of Alans and would be delayed. A heated debate ensued among Gratian’s officers as to how to proceed. Sebastian urged Valens to strike now before the barbarians cut them off. The scouts put the Goths’ numbers at no more than 10,000, half the size of Valens’ force. He argued that if they struck fast enough, victory was assured. Richomeres pleaded with Valens to stay put and await Gratian’s arrival. If the scouts were wrong, the combined eastern and western army could deal with whatever the barbarians threw at them.

While the generals argued, an Arian priest claiming to be an emissary from Fritigern arrived in Adrianople with a surprising offer. The old man announced that the Goths were still willing to accept the original terms of land for military service. If Valens were to ensure that this time the terms were honored, so would Fritigern. Before leaving, the priest slipped Valens a note from Fritigern. It said that the Gothic leader and his people desperately wanted to avoid battle and that a Roman show of force was all that was needed to convince the Goths to lay down their arms.

This was all Valens needed to hear. He now had definitive proof that the Goths were on their last legs. If he moved quickly enough, he could defeat Fritigern decisively without his nephew’s help and win all the glory for himself. Richomeres and a few other officers continued to urge patience, but Valens refused to hear it. At dawn on August 9, ad378, he confidently led his army out of Adrianople toward what he was sure would be the crowning achievement of his reign.

Valens’ roughly 20,000 men more closely resembled a medieval army than one of Caesar’s legions. Years of warfare with barbarian tribes had profoundly changed the look and armament of the Roman military. Iconic classical features like the segmentata plate armor, the rectangular scutum shield, and the short, wide gladius sword had long since disappeared. They were replaced by barbarian-style chain mail tunics, oval shields, and longer, narrower swords. Even the famous pilum throwing javelin had been largely superseded by a taller, heavier stabbing spear, though smaller throwing spears were still carried.

Another example of the changing face of Roman warfare was the growing reliance on cavalry. Almost a quarter of Valens’ troops were on horseback. This percentage was a significant increase over classical Roman armies. His cavalry units would have varied from lightly armed skirmishers and horse archers to heavily armored cataphracts like those fielded by Persian, Armenian, and future Byzantine armies; however, most would have been armed and armored similar to the infantry with chain mail shirts and oval shields, but longer swords and spears more practical for cavalrymen.

The Romans followed the main road northwest toward where Valens’ scouts reported the Goths to be. They advanced in a long column with the cavalry at the head and rear and the infantry in the center. It was the height of an extremely hot Balkan summer and by mid-morning the temperature was already brutally high. The army plodded along the rough, hilly terrain for about eight miles until stumbling upon a series of Gothic carragos on a low hill in the middle of a dry plain. Valens was thrilled to discover that his scouts were right that the Goths had no more than 10,000 warriors. They were joined by many thousands more women and children, but they were of no concern. Despite the fact that it was now early afternoon and his troops and horses had been roasting all day in their armor without food or rest, Valens gave the order to deploy for battle.

Had Valens bothered to reconnoiter the surrounding countryside, he probably would have discovered that the warriors on the hill were only part of Fritigern’s force. Foraging not far away were 5,000 Gothic horsemen. Most were members of the Gothic Greuthungi tribe, which had taken advantage of the chaos in the Balkans to cross the Danube the summer before. They were commanded by the Gothic chieftains Alatheus and Saphrax and would likely have included contingents of Huns and Alans. Gothic horses were larger than their Roman counterparts and Gothic horsemen rode into battle with a heavier assortment of armor and weaponry, including scale armor, large, round shields, and long lances.

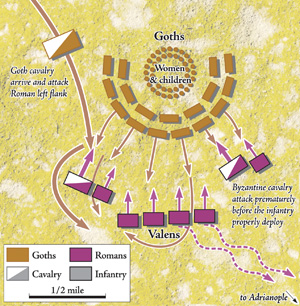

The Romans deployed in their standard battle formation of infantry in the center and cavalry on either side. Valens and his staff took position with his household cavalry on the right side of the line, which was the traditional place of honor. Virtually the entire army was committed to battle, and only a small force of Batavian auxiliaries was held in reserve some distance to the rear. Moving tens of thousands of troops from a marching formation to a battle line was a difficult undertaking and Valens, anxious to engage to Goths as soon as possible, quickly grew frustrated by the slow progress.

Fritigern had the opposite problem. Though he also deployed his troops on the crest of the low hill in front of the wagon forts, seemingly ready to do battle, he was desperate to avoid a fight at all costs until his cavalry returned from their foraging. To slow and confuse the Romans, he had his men light brush fires across the plain that sent dark clouds of acrid smoke wafting into the faces of the already exhausted and dehydrated legionaries. He also sent emissaries to the emperor in an effort to barter for time through negotiations. Valens, probably to buy more time for his own deployments, agreed to negotiations but only if hostages of appropriate rank were exchanged.

While the emissaries raced back and forth, Valens’ troops grew more and more restless as they broiled under the blazing sun on the open plain. Suddenly, without order, the Roman cavalry on the extreme left charged the Gothic line. The sources are conflicted on whether this was due to disobedience or overzealous skirmishing. Regardless, it was a foolish move. From atop their elevated position, the Goths patiently waited behind their shield wall until the cavalry was in range then let loose a torrent of arrows and other projectiles. Before they had even reached the hill, the Roman horsemen took heavy casualties and they soon retreated in disarray back to their lines.

In the center, the infantry units watched the attack on the left and assumed that they had missed their own orders to advance in support of the cavalry. Up went the rumbling barritus war cry, and once again without orders thousands of men began marching forward, relieved that they were at last coming to grips with the enemy. From his position on the right, Valens was aghast, but there was little he could do. As an experienced commander he knew how difficult it was to pull back even the most disciplined troops once they had been committed to combat. He could only sound the trumpets and watch with bated breath as the Roman attack officially began.

The Goths watched the ironclad mass of Romans begin to move and they steeled themselves by shouting the names of their ancestors, blowing their war horns, and banging their weapons against their shields. They pelted the advancing Romans with the same arrows, stones, and javelins that brought down the cavalry, but Valens’ better-armored infantry simply raised their shields in unison and continued marching forward, shoulder to shoulder, with lockstep discipline, as the projectiles lodged harmlessly in the reinforced wood and leather. When the Romans were at the foot of the hill, the Goths let out a final bellowing war cry then rolled down the slopes like a human avalanche.

The Goths collided with the Roman front line and the air rang with the thunderous clap of thousands of wooden shields slamming together. The savagery of the Gothic charge stopped the Roman advance dead in its tracks. The Gothic warriors were not just fighting for their own lives, they were fighting for the lives of their women and children cowering in the wagon forts. They hacked wildly, like men possessed, at the Roman shield wall with their clubs and battleaxes, cleaving apart any legionary foolish enough to lower his guard even for a second. Accounts tell of Goths with hamstrung legs and even severed limbs fighting tooth and nail from their knees like wounded animals. Even the most battle hardened of Valens’ troops surely must have been struck by the barbarians’ defiant resolve.

The Roman center briefly buckled from the momentum of the Gothic charge but recovered and held firm. The elite palace legions had deployed in the center. As the most senior and experienced units, they could be relied on to retain their composure even in the fiercest of fighting. On the Roman left, which was still in the process of deploying when battle was joined, the situation was much more precarious. There the advancing infantry ran into some of the retreating cavalry, disrupting their cohesion. Worse yet, as often happens when assaulting a defensive circle, gaps began to appear in the line; in this case, between the cavalry on the extreme left and the infantry contingents to their right. The Goths saw this and they intensified their attacks in this direction, which drew more and more Roman troops toward the left.

For some time the battle ebbed and flowed with neither side gaining a discernable advantage. The gap on Valens’ left continued to grow unsettlingly wide, but on his right and center, the infantry had begun to push the Goths back up the hill and were edging dangerously close to the wagon forts. Just as it seemed that the tide was at last beginning to turn in favor of the Romans, suddenly there arose from the distance a faint but distinct rumble. It grew louder and louder until out from around the western side of the hill, through the smoke, poured thousands of Gothic cavalrymen. Alatheus and Saphrax had returned.

The Gothic horsemen plunged into the weakened Roman left, easily brushing aside the disordered Roman cavalry. By then most of the Roman infantry were utterly exhausted and unprepared for this dangerous new threat. Most would have also shattered their spears in the close-quarter fighting, leaving only their swords, an ineffective weapon for facing a cavalry charge. Entire cohorts disappeared beneath the Gothic horsemen as they drove inexorably through the Romans, trampling and skewering anything in their way. The terrified legionaries crashed into each other trying to flee, and soon the entire Roman line began to crumble and devolve into a panicked mob.

From his position on the right flank, a horrified Valens watched his left flank melt away. He tried to rally his men, but before he could, more Gothic horsemen swept out from around the eastern side of the hill and a similar scene began to play out on his right. Valens immediately ordered his Batavian reserves into battle in a last-gasp effort to stave off disaster. But they had already fled the field and were nowhere to be found. There was nothing he could do but watch helplessly as the pincers of the Gothic cavalry closed around his army. Realizing the inevitable, he bravely galloped into the fray and joined his palace guards, who were still standing firm in the center.

The surrounded Roman army rapidly degenerated into a chaotic jumble of terrified men and maddened horses. With every passing moment the Gothic ring tightened, squeezing the Romans until they could barely lift their weapons to defend themselves. From all directions wild-eyed Goths hammered and slashed at the hapless legionaries while a storm of deadly projectiles rained overhead. It soon became impossible to tell friend from foe. The cloud of dust thrown up by the Gothic cavalry was so thick that it blotted out the sun and made it increasingly difficult to breathe, let alone see. Amid the press of shields, many exhausted Romans choked and collapsed to the blood-soaked grass to be trampled to death by their comrades. Eventually, officers stopped trying to shout orders over the din of screaming men, whinnying horses, crashing weapons, and splintering shields. It fell on each man to do his duty as best he could from where he stood.

The doomed legionaries did their duty well and the fighting dragged on for hours under the blazing sun. Many Gothic warriors briefly withdrew to the wagon forts to refresh themselves and catch their breath before resuming fighting. The Romans had no choice but to fight until their last ounce of strength gave out. Gradually the mass of surrounded Romans began to diminish until only a small cluster remained to make a heroic last stand. As dusk descended on the battlefield, they too were cut down and the last ember of Roman resistance was snuffed out.

At some point in the fighting, it is not known exactly when, Valens was felled by an arrow and disappeared beneath the bloody piles of corpses, never to be seen again. Trajan and Sebastian suffered similar fates. Well into the night, the Gothic cavalry pursued the fleeing remnants of the Roman Army, and by morning the surrounding countryside was littered with dead men and animals. Sadly, many of the Roman survivors lucky enough to make it back to Adrianople were denied entry by the panicked citizenry.

For the Eastern Roman Empire, the defeat at Adrianople was a catastrophe of almost incomparable proportions. In one day, its military and political power structure had been almost completely destroyed. Within days, wild panic had swept across the east and contingents of Gothic mercenaries as far away as Mesopotamia were butchered in revenge by hysterical Romans. Upon receiving the news of his uncle’s defeat and death, Gratian did not even bother trying to subdue the victorious barbarians. He turned his army around and returned to the west, leaving the entire Balkan Peninsula at the mercy of the Goths and their allies.

Incredibly, the aftermath of the battle proved anticlimactic. Fritigern followed up his momentous victory by first besieging Adrianople and then Constantinople; however, both sieges quickly failed and the Goths returned to raiding and pillaging the rich lands of the western Balkans. Luckily for the Romans, the Goths were a steppe people with an aversion to siege warfare. Fritigern was even famously heard to comment that “he had no quarrel with stone walls.” The end of humanity that St. Ambrose had predicted never occurred.

For almost four years, the barbarians rampaged across the Balkans with little to stand in their way. Rather than claim the east for himself, Gratian gave the eastern crown to Theodosius, a talented young general from Roman Spain. There were many who said that the new eastern emperor had been given a fool’s errand, that the east was lost to the barbarians. But Theodosius breathed new life into the army of the Eastern Roman Empire. He launched a massive recruitment drive and raised a new army. He even enlisted Gothic renegades to shore up his numbers. Through a combination of blunt force and shrewd diplomacy, he convinced Fritigern to accept the original agreement of troops for land. Although the empire would never be the same after the trauma of Adrianople, the Gothic Revolt was over and peace returned to the Danube.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments