By John Walker

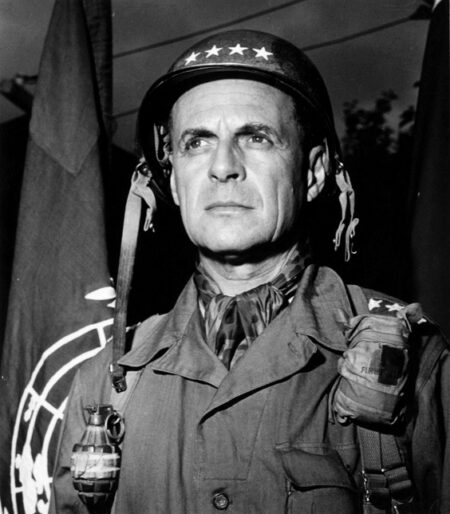

As Lt. Gen. Matthew Ridgway boarded a flight to Tokyo, Japan, on December 23, 1950, on his way to a meeting with General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, he was not fully aware of the depth of the crisis still unfolding on the frozen Korean peninsula, where American-led United Nations forces and their South Korean allies, who were seemingly on the verge of complete victory in North Korea, were now suddenly on the brink of collapse and perhaps outright defeat. MacArthur, the commander-in-chief of U.N. forces fighting in Korea, had handpicked Ridgway to assume command of U.S. Eighth Army after its commander, Lt. Gen. Walton Walker, was killed in a traffic accident.

When they met three days later, MacArthur painted a bleak picture of the situation in Korea. MacArthur apparently had no idea how to stop the tens of thousands of advancing Chinese Communist troops who had halted, then routed, his end-the-war offensive north of the 38th Parallel to the Yalu River. Nevertheless, MacArthur assured Ridgway of his support. “The Eighth Army is yours,” he told Ridgway. “Do what you think best.”

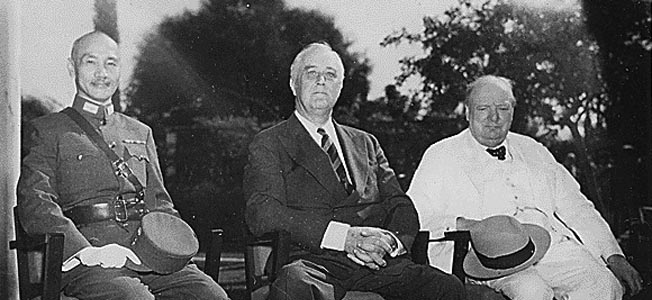

Chairman Mao Zedong, the leader of the People’s Republic of China, had decided to aid beleaguered North Korean Premier Kim Il-sung beginning in mid-October 1950 by sending more than 300,000 Chinese soldiers across the Yalu River into North Korea. They crossed the frontier unhindered, for MacArthur’s chronically ineffectual intelligence services had failed to detect their presence.

Ridgway flew to South Korea that afternoon. Although he had distinguished himself in World War II commanding the 82nd Airborne Division at Normandy and the XVIII Airborne Corps during Germany’s Ardennes Offensive, Ridgway knew little about Asia, and even less about Korea.

Upon his arrival, Ridgway found Eighth Army a demoralized force with more than a few shaken officers talking openly about evacuating the entire peninsula. Unconventional Chinese tactics and behavior had inflicted a severe psychological blow upon enlisted men and officers alike. These tactics consisted, for the most part, of seemingly endless human-wave attacks at night.

After abandoning massive amounts of food, weapons, and ammunition to the enemy, Eighth Army’s humiliating month-long flight from the Chongchon River in northwest Korea had finally ended well below the 38th Parallel. The 1,250-mile retreat was the longest of its kind in the annals of the U.S. military.

The U.S. X Corps’ performance on the northeastern front—especially the 1st Marine Division’s epic fighting withdrawal from the frozen Chosin Reservoir—had been far more respectable, but nonetheless all U.N.-ROK forces had been driven from North Korea by Christmas 1950. Although Chinese Marshal Peng Dehuai had shocked the world with his triumphant month-long winter counteroffensive that began on November 24, 1950, it had cost the attackers 80,000 casualties, one-fourth of their total strength.

As he toured the front for three days in an open jeep in freezing weather, meeting with his corps and division commanders, and ROK division commanders as well, Ridgway told them the same thing he had told South Korean President Syngman Rhee. “I’ve come to stay,” he said.

Finding the Communists had temporarily halted their advance along a line just above the 38th Parallel on December 24, 1950, awaiting much-needed supplies of food and ammunition, Ridgway thought about organizing a quick counterattack but reconsidered when he reached the front.

“I discovered our forces were simply not mentally and spiritually ready for the sort of action I had been planning,” he said later. “The men I met along the road, those I stopped to talk to, all conveyed to me a conviction that this was a bewildered army, not sure of itself or its leaders, not sure what they were doing there. The leadership I found in many instances sadly lacking, and I said so.”

With his trademark grenade and battle dressing attached to his shoulder straps at all times, Ridgway set about restoring Eighth Army’s morale, quickly dismissing the idea of evacuating Korea. A proponent of defense-in-depth, Ridgway put his engineers and several thousand local laborers to work erecting a deep defensive zone south of the Han River. It consisted of four successive fortified lines dug and prepared on an unprecedented scale, each with a trench system, concertina wire, bunkers, mines, artillery emplacements, and radio communications.

Ridgway issued orders instructing commanders from regiment-sized units on up to stay off the roads and fight their way through the hills, where the enemy was holding the high ground. The new commander demanded speed and aggressiveness: If an enemy appeared on a unit’s front, he called for immediate deployment of troops to protect the flanks and prevent breakthroughs. Ridgway showed no hesitation relieving officers who failed to meet his high standards of combat performance.

Studying the terrain as he flew over the front, Ridgway knew the Communists would resume their offensive soon. He not only took steps to contain the advance; he adopted war-of-attrition tactics to inflict maximum punishment upon the enemy. Ridgway knew he would have to give up key ground, including Seoul, but he was convinced the Communists were nearing the end of their long and fragile supply line.

Supremely confident after the stunning successes won in the last two months of 1950 and hoping to force the U.N. forces to abandon South Korea, Chairman Mao had decided, against the objections of his military command, to widen the conflict by crossing the 38th Parallel and expelling all UN forces from Korea. His Third Phase Offensive, launched on December 31, 1950, was the first test for Eighth Army’s new commander but lasted, surprisingly, little more than a week.

“We were killing them by the thousands, but they just kept coming,” said Ridgway. After several ROK divisions on the flanks, which were ill-trained, ill-equipped, and ill-led after suffering horrific losses earlier in the war, completely collapsed, Ridgway abandoned Seoul on January 4, 1951, and withdrew south of the Han River.

Eighth Army and X Corps withdrew 40 miles to the defensive line that had been prepared for them “as a fighting army, not as a running mob,” Ridgway said. There, thanks to the lavish use of artillery and air power, the U.N.-ROK front stabilized and held. The Communists had indeed outrun their logistical capability and for the time being were unable to press beyond Seoul.

Finding the Communists had abandoned their most advanced positions, Ridgway ordered Eighth Army to conduct a reconnaissance-in-force beginning on January 25, 1951, which became Operation Thunderbolt, the first U.N. counterattack of the year, a show of force meant to dislodge enemy units from the south side of the Han River, threaten Seoul, and instill confidence within U.S. 2nd Infantry Division’s ranks. With the entire front line moving northward as one from each phase line to the next, backed by heavy artillery and air support, the advance concluded with friendly forces reaching the south bank of the Han River in strength by early February.

On February 11, though, the resupplied and reinforced Communists, some 200,000 strong, launched their Fourth Phase Offensive, a massive attack southeastward from Seoul across the waist of the country. The initial assault against X Corps near Hoengseong drove two U.N. divisions back, leaving 2nd Infantry Division’s 23rd Regimental Combat Team, along with a French infantry battalion, surrounded at the strategic crossroads town of Chipyong-ni, 50 miles east of Seoul and 40 miles south of the 38th Parallel.

After the X Corps’ commander, Maj. Gen. Edward Almond, ordered 23rd RCT’s commander, Colonel Paul Freeman, to fall back 15 miles to the south, Ridgway countermanded the order. The Eighth Army commander had decided to gamble and, against daunting odds—Freeman’s 4,500 men squared off against 20,000 Communists—to stand their ground and fight.

In some of the war’s most savage fighting, the 24th RCT and its French allies beat back massed ground attacks over three nights beginning on February 13, supplied by air-drops and supported by UN artillery barrages and bombs, bullets, and napalm dropped by U.N. bombers upon advancing enemy formations. Short of essential supplies and with their casualties mounting, the Communists began withdrawing northward, having reached the high-water mark of their advance into South Korea. The defeats at Chipyong-ni and the Third Battle of Wonju in the middle of February left the enemy withdrawing across the entire front. Although the sizes of the forces involved were relatively small, the twin victories marked a huge turning point in the war. Having failed to drive U.N. forces into the sea, the Communists were now themselves being driven back.

As the enemy began pulling back from Chipyong-ni in mid-month, Ridgway kept the pressure on. He started with Operation Killer on February 21. The operation was a full-scale attack northward by seven divisions, designed for the maximum exploitation of firepower to kill as many Communists as possible.

A follow-on operation, known as Ripper, began on March 6. The new operation was a large-scale, ambitious effort to drive the enemy back to the 38th Parallel through another series of so-called phase lines. After Ripper opened with the largest artillery barrage of the war, U.N.-ROK units pushed north and encountered only light resistance as tens of thousands of Communists headed north to escape the deluge of shells. The advancing troops retook Seoul on March 14. After changing hands four times over a year, the once-vibrant capital now lay in ruins, most of its buildings leveled, its population down to 200,000 from a pre-war high of 1.5 million, most suffering from disease and severe food shortages.

Attempting to stem the surging U.N.-ROK tide, Peng marshaled the manpower of three field armies, a staggering 700,000 men, for a massive Spring Offensive that began on April 22. He sent 340,000 troops in 27 divisions against the U.S. I and IV corps along a 40-mile front north of Seoul.

After a week of heavy fighting at the crucial battles at Kapyong and the Imjin River, the enemy’s advance was halted at the so-called No-Name Line north of Seoul by the end of April. By this time, tens of thousands of Communists were fleeing north and thousands more, many of whom were sick, starving, and frostbitten, surrendered to the U.N.-ROK forces. After the crushing defeats of late winter and spring 1951, the Chinese gave up any hope of unifying Korea under Kim’s rule, and the conflict degenerated into an ugly war of attrition along the 38th Parallel, while negotiations to end the fighting began in July 1951.

A letter MacArthur had written to a U.S. Congressman that advocated the use of Nationalist Chinese (Taiwanese) troops in Korea surfaced on April 5. This new controversy again unsettled Truman and his Western allies.

The most unpalatable part of MacArthur’s strategy for victory was his belief that it was acceptable to use atomic weapons to defeat world communism. Truman was adamantly opposed to the use of nuclear weapons for such purposes, and the president made every effort to keep the conflict confined to the Korean peninsula.

The conflict between Truman and MacArthur had finally reached the tipping point. Truman relieved MacArthur on April 11, replacing him with Ridgway. Truman then appointed Maj. Gen. James Van Fleet to command the Eighth Army.

Maintaining their “war of attrition” tactics, Ridgway and Van Fleet found time not only to build the South Korean army into a formidable fighting force, but also to integrate African-American soldiers into previously segregated units in the Far East Command, a policy soon matched throughout the American armed forces.

Having largely turned against the war, Americans welcomed the July 1953 armistice, which allowed for the cessation of hostilities and the exchange of POWs. But because Kim Il-sung and Syngman Rhee never signed a formal peace agreement, the two Koreas remain in a state of war to this day. None of this, though, detracts from Ridgway’s grand achievement leading the Eighth Army to victory on the Korean Peninsula.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments