By David A. Norris

Lieutenant General Armand-Charles de Gontaut, Marquis de Biron, led a party of foragers ahead of the French Army. His men scoured farms and villages in the Flemish countryside outside the fortified city of Oudenarde. Twenty-five years with the army had taken Biron into many a dangerous scrape in the Low Countries, Germany, Ireland, and Italy. But on this July day he expected nothing more dangerous than the protests of cantankerous farmers. The enemy army under Sir John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, was assuredly 15 miles away to his south.

Suddenly, the country summer sounds of buzzing bees and chirping birds were drowned out by gunshots. Biron rode forward to investigate and saw to his shock that his foragers were under fire by several squadrons of enemy cavalry. Using a windmill as an observation post, the marquis saw that scarcely 1,000 yards away several newly assembled pontoon bridges spanned the Scheldt River. Beyond the bridgehead, clouds of dust announced the approach of Marlborough’s army. A courier dashed away with alarming news for Biron’s commanders. Marlborough’s army seemed to have made a 15-mile jump, and July 11, 1708, was going to be the date of the Battle of Oudenarde.

In the late 1690s, European diplomats and leaders watched an impending political crisis. Sickly and feeble, King Charles II of Spain was the last of the male line of the Hapsburg rulers of Spain, and he had no son to receive his crown. In his will, Charles II designated a near relative, Philip, Duke of Anjou, as his heir. Philip was a grandson of Charles II’s deceased half-sister Maria Theresa and her husband, King Louis XIV of France. Furthermore, Philip’s father was Louis, Dauphin of France, and the son and presumptive heir of Louis XIV.

At the dawn of the 18th century, France was Europe’s top superpower. Spain was no longer as formidable as it had been in the 16th century, but it possessed a considerable military establishment and an extensive overseas empire. The prospect of Paris and Madrid united under a single crown alarmed the enemies of France and set off the War of the Spanish Succession in 1702. England, the Dutch Republic, and the Austrian Hapsburgs were the primary members of an anti-French coalition sometimes called the Grand Alliance (after an earlier coalition that fought the French during the Nine Years’ War in the 1690s). Contemporaries referred to the coalition forces as the allies, or the confederates.

Joining the alliance were several other nations, including Portugal, Denmark (the husband of England’s Queen Anne was Prince George of Denmark), Savoy, and adherents of the Holy Roman Empire including the German states of Prussia and Hanover. Their motives varied; England sought to counter the power of France, while the Austrians primarily entered the war to gain the Spanish crown for their claimant, who they considered to be Charles III of Spain.

Fighting spread across the Iberian Peninsula, the Low Countries, Italy, and Germany. Also dragged in were the English and French colonies in North America. English colonists called the conflict Queen Anne’s War.

Campaigning in Flanders started again in 1708 with the arrival of warm weather. The allies held much of Flanders after their victory at Ramillies in 1706. Commanding the army of the coalition was an Englishman, Sir John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough.

Churchill was born to a Dorset family that was left in reduced circumstances after the English Civil War. At the age of 17, Churchill entered the army as an ensign. His military service took him to Flanders and Ireland, and he also served in increasingly important roles in government. Raised to an earldom in 1689, he was further raised to duke in 1702. Early in the War of the Spanish Succession, he was appointed captain-general of the allied forces. He proved a fortunate choice for the command of the international coalition, as he was not only an exemplary army officer but a skilled diplomat. His care and consideration for his soldiers’ welfare earned him their devotion, and the affectionate nickname “Corporal John.”

For the campaign of 1708 in Flanders, a former comrade of Marlborough’s would rejoin him. Prince Eugene of Savoy was born in Paris and raised in the court of Louis XIV. As a young man, he was awkward and frail in appearance, and his family tried to push him toward a career in the Church. After his mother was involved in a court scandal, he was refused an army commission by Louis XIV. Eugene’s brother had already died fighting in the Austrian service. The young prince went to Vienna, where he pledged allegiance to the Hapsburgs. He arrived in 1683, and quickly distinguished himself in the fighting that expelled the Ottoman Army from its siege of Vienna. By the age of 30, he was a field marshal.

Eugene and Marlborough each found a kindred spirit in the other. They worked in such harmony in a military setting that a contemporary commentator remarked that “from the moment [they met], they acted with such Unanimity as if one Soul had inform’d two bodies.” Soon after their first meeting, they worked together to win a decisive victory over a French army led by Camille d’Hostun, Duke of Tallard, at Blenheim in 1704.

In Flanders, Marlborough made an effective fighting force from what could have been a hodgepodge of quarreling rivals. Relatively few of Marlborough’s soldiers were his own countrymen. Suspicious of standing armies, England’s people and Parliament supported a small military establishment, and many of its units were needed to hold down Ireland, Scotland, and the colonies. By one count, Queen Anne had only 18 battalions of infantry and a mere seven cavalry squadrons in Flanders. British regiments then generally had only one battalion, so contemporary English sources usually refer to battalions instead of regiments. At that time, an infantry battalion averaged about 500 men and a squadron of cavalry about 120.

Soldiers of the German states, the Dutch Republic, and Denmark made up most of the allied ranks. Some Danish and German troops were in the pay of Great Britain, and the Dutch enlisted some Scots battalions.

Marlborough hoped to push the French out of Flanders and pursue them across the border into the homeland of Louis XIV. With the English duke were 90,000 troops in Flanders. Guarding the Rhine was a slightly larger force under George, Prince-Elector of Hanover (the future King George I of Great Britain). In Marlborough’s plan, 40,000 men would remain with the Elector. Prince Eugene would take 45,000 of the Elector’s troops from the Moselle River at Koblenz and join the main force in Flanders.

In Flanders, French King Louis XIV inflicted an awkward arrangement on his army by designating two commanders. Louis Joseph, Duke of Vendome, was a remarkable military tactician with considerable wartime experience. He was also an illegitimate great-grandson of France’s King Henri IV. It is worth noting that Vendome’s mother’s younger sister was the mother of Prince Eugene. The other was the 26-year-old Louis, Duke of Burgundy. He was a grandson of Louis XIV and the son of the heir to the French throne, Louis, Dauphin of France.

Vendome was conspicuously slovenly and shabby in an age of elegance. A life of self-indulgence had made this notorious libertine quite fat at the age of 56. He could be insufferably rude to his peers and superiors, and the Duke of Burgundy could just barely abide him. Yet at the same time, Vendome was good natured toward those of lower rank. His soldiers adored him, in part because he permitted them the drinking and carousing he allowed himself.

Voltaire, who saw Vendome’s style as “a mixture of activity and indolence,” wrote that the duke often slept until 4 pm. He was reluctant to leave comfortable campsites, preferred a late start and an early halt to a day’s march, and neglected elementary precautions such as posting sentries and sending out patrols. In battle, though, Vendome shed his decadence and laziness and became a bold and inspiring leader. Flamboyant white plumes atop the duke’s hat allowed his men to see him, and he was often in the very thick of the fight. In the midst of a battle, he always seemed to know the precise moment to exploit a new opportunity with a decisive charge. He was successful while campaigning in Italy, and he won a victory over Prince Eugene’s army at Cassano in 1705.

Already affronted by Vendome’s insolent manner and sloppy appearance, the Duke of Burgundy also had a strong religious streak, and so he was doubly offended by the older duke’s lifestyle. Officially, the king’s grandson headed the French army in Flanders, but he was ordered to share command with the more seasoned Vendome, who resented Burgundy as an interfering amateur. A disagreement between the two could create a deadlock, halting vital decisions while messengers dashed to Paris to get orders from the king.

Politics pushed two prominent British Jacobites (adherents of the deposed House of Stuart) into high rank in the French Army. James FitzJames, Duke of Berwick, was Marlborough’s nephew. A natural son of the deposed British monarch James II, Berwick’s mother was none other than Churchill’s sister Arabella. Brought up in France, Berwick chose a military career. He left the French service when his father ruled England but returned to France after the collapse of the Jacobite cause and the final exile of James II.

Also with the French was the legitimate son of James II, James Francis Edward Stuart (known as James III and VIII to his partisans, and to anti-Jacobites as the Pretender). Earlier in 1708, Stuart sailed for Scotland with a force of French ships and troops intent on sparking a rebellion and reclaiming the crowns of England and Scotland. The invasion was prevented by the Royal Navy and stormy weather. Returning to Europe, the Stuart claimant returned to the French Army, where he was known as the Chevalier de St. George.

In May, the allies’ main camp was at Louvain, perhaps 15 miles east of Brussels. The French were encamped at Braine-l’Alleud, about a dozen miles south of Brussels, and close to the site of the future clash at Waterloo.

Flanders, long denied self-rule, was caught up in wars between the major European powers. The famed French military engineer Vauban rebuilt Oudenarde’s defenses when the town came under temporary French rule in the 1670s. Ceded back to Spain, the region was retaken by France in 1701. The allied victory at Ramillies ousted the French in 1706. Dutch garrisons guarded the conquered territory, although Marlborough was uneasy about the way the Hollanders treated the populace.

The duke was right to worry, as the heavy-handed occupation by the Dutch led to the loss of two key points in the rear of the allied army. French spies posing as deserters took a city gate at Ghent on July 4. Heavily pro-French, the city fell without firing a shot. Bruges opened itself to the French one day later. Losing these cities cost Marlborough the use of the Scheldt and Lys Rivers as transportation routes, and complicated his access to supplies and communications coming from England.

From Braine-l’Alleud, the French marched toward Oudenarde, 30 miles to the northwest. Situated 10 miles up the Scheldt from Ghent, Oudenarde was still under the control of a small allied garrison.

After he learned that the French were on the move, Marlborough was desperate to strike the enemy before they could cross the Dender River. But the French generals pushed their troops hard, and the host made it across the river. Because of this, the allies could do no more than attack the rear guard.

On the night of July 6, the allied army camped at Asche, about 10 miles northeast of the point where the French crossed the Dender. Prince Eugene, worried that a battle would occur before his troops could reach Flanders, dashed ahead of his troops and arrived at Asche to join the army.

Eugene and Marlborough believed that to cover their move against Oudenarde the French needed to take Lessines, a town on the Dender. The allied commanders intended to get to Lessines first. Leaving Asche at 2 am on July 9, the allied vanguard under Maj. Gen. William Cadogan reached Lessines at midnight after a march of almost 30 miles. By the time the rest of the allied army arrived, Cadogan’s men had several pontoon bridges ready. The army pressed on toward Oudenarde in anticipation of a battle on the south bank of the Scheldt in front of the city.

Vendome and Burgundy now had an enemy army between them and France. They altered their plans and aimed to cross the Scheldt a few miles downstream from Oudenarde. Then, on the left bank of the river, they would be able to fend off an attack and either move against Oudenarde or protect Ghent and Bruges. It was a cautious strategy to be sure, but such prudence fit with Louis XIV’s desire to avoid ruinously expensive battles when possible.

One of the few things that the quarreling French commanders agreed on was their belief that the allies would linger around Lessines for a while. So it was 10 am on July 11 before the French even started over the Scheldt at Gavres, about 21/2 miles northeast of Oudenarde.

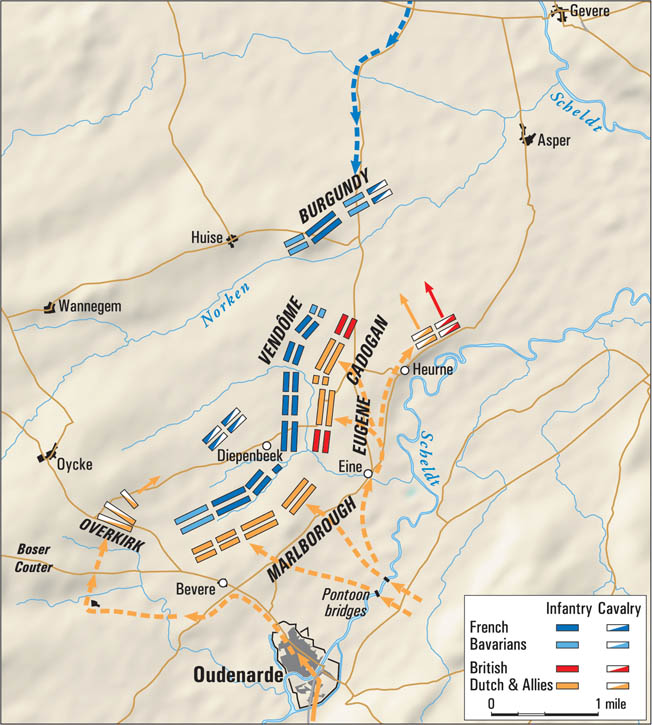

In contrast, the allies moved with surprising speed. Early on the morning of July 11, Marlborough detached Cadogan to move ahead to the Scheldt and occupy the village of Eine, just northeast of Oudenarde. With Cadogan were 16 battalions of infantry, 30 squadrons of cavalry, and 26 guns. The rest of the army departed from Lessines in Cadogan’s wake.

Cadogan was Marlborough’s quartermaster general. An able administrator and staff officer, Cadogan was to prove himself as a battlefield tactician that day. After another swift march, Cadogan had his first detachments across the Scheldt by about 10 am. His engineer troops swiftly assembled five pontoon bridges just east of Oudenarde. Marlborough’s men called their pontoons tin boats, as the wooden pontoons were covered with sheets of metal to protect the hull planking.

Plodding across the river late on the morning of July 11, the French army gradually assembled north of the Norken River, a tributary of the Scheldt. Their commanders thought they had ample time to fall upon Marlborough when he crossed the Scheldt.

Among the first to reach the left bank of the Scheldt were Burgundy and Vendome and their staff officers and attendants. Unconcerned about enemy moves, the leaders and their aides settled down to what they expected to be a quiet and leisurely luncheon.

At that point, Biron’s messenger interrupted the high officers’ idyllic meal. Enjoying the comfort of some shade trees, Vendome brushed off the courier’s report as a mistake. Such a rapid march by the enemy was impossible. Biron dispatched a staff officer with a second message, which only further irritated the duke. Only when a third urgent message arrived from Biron did Vendome believe it. He mounted his horse, exclaiming that the only way that Marlborough’s army could possibly be so close was that “the devil must have brought them.”

Officers with an eye for terrain quickly took in the lay of the land. For the most part, they would have seen flat to gently rolling farmland, but the open fields were slashed by deep ditches and partitioned by thick hedges that would impede cavalry. The main highway to Ghent and some of the country roads were lined on both sides with hedges and ditches. Several small villages, each of them a mere handful of buildings lining a road, were scattered across the land between Oudenarde and the Norken. Numerous windmills and village churches rose above the fields as prominent landmarks.

South of the Norken River, to the west of the French, was a hill topped by the village of Oycke. Below the eastern slope of this hill, called the Boser Couter, there were two small streams. One, called the Marollebeek, flowed into another called the Diepenbeek, which in turn emptied into the Scheldt. The stream valleys were lined with low, boggy ground covered with a thick layer of brush and scrubby trees.

Vendome ordered his army to form south of the Norken. There was a chance of catching the enemy in the vulnerable situation of crossing the Scheldt and cutting off and destroying a substantial part of the coalition army. Intending to anchor his left at Heurne, the duke planned his line to run roughly west past the villages of Bevere and Mooregem. As a beginning, seven battalions of Swiss under Brig. Gen. Francois-Louis Pfeiffer were dispatched to hold Heurne.

At that point, Burgundy overruled Vendome and demanded that the army pull back to a more defensible line on the northern bank of the Norken. But no one warned the Swiss battalions of the change in plans. They carried out their orders but under a misunderstanding went to the village of Eine instead of Heurne.

Cadogan sent Brig. Gen. Joseph Sabine’s brigade against the Swiss battalions at Eine. Charging ahead with their bayonets, Sabine’s men overwhelmed the Swiss. Three entire battalions were captured, and the other four battalions fled in disorder with the loss of many killed or taken prisoner. General Pfeiffer was captured, and two of his colonels were among the dead.

After the rout of the Swiss, Hanoverian cavalry under Lt. Gen. Joergen Rantzau of Denmark attacked several French cavalry squadrons that still lingered at Eine. With one of Rantzau’s squadron commanders, Colonel Johann Albrecht von Losecke, was the son of the Prince-Elector of Hanover. Then aged 24, the young Prince George of Hanover was the future King George II of Great Britain. A French bullet killed Prince George’s horse. Von Losecke feared that the young royal would be trampled to death while on foot amid the charging horses. The colonel rode to the prince and offered his own horse. In the process of dismounting, the colonel was shot down by a musket ball.

The prince’s father had intended for him to learn military matters in camp at a safe distance from the fighting. But the young royal refused to leave the field. John Marshal Deane of the Foot Guards wrote that Prince George “charged … on foot sword in hand: bringing an Officer of ye Enemy prisoner.” Rantzau’s Hanoverians routed the French cavalry and pursued them to the Norken.

Most of the artillery of both armies was too far away to take part in the coming battle, so the Battle of Oudenarde was largely to be an affair of foot and horse troops fighting with musket and saber. As was his custom, Marlborough made plans as he went. He sent units into action as soon as they arrived, and he posted them wherever they were most needed at the moment. He gave command of the right to Prince Eugene and fed the prince a steady supply of reinforcements to ensure his success.

By 4 pm the allies had done nothing to attack the main French force. The Duke of Burgundy pushed his center and right across the Norken, hoping to break up Marlborough’s army before he could assemble all of his troops. Most of Cadogan’s men were still at Eine, other than two Prussian regiments that he had posted about half a mile north at Groenewald. Hanoverian battalions manned a line south of the Diepenbeek. British cavalry gathered at Bevere, north of Oudenarde; Prussian cavalry held the allied right near Heurne.

Vendome saw that he might be able to smash the Prussians at Groenewald. He sent a Captain Jenet to Burgundy imploring him to send the rest of the army from beyond the Norken. The prince had already committed the Marquis of Grimaldi with his cavalry. Grimaldi’s vanguard, upon riding into the wetlands along the Marollebeek, balked and reported that they were facing an impenetrable swamp. When Jenet found the prince, Grimaldi’s advance had been called off, and thousands of troops that could have hammered the allied units waited idly by. Jenet rode back to report the news, but was killed before he could reach Vendome.

At Groenewald, the Prussians held on against long odds using the thick hedges as cover until they were reinforced by Cadogan. Twenty more battalions under the Duke of Argyll bolstered the allied line. The French outflanked the allied left but were driven back when fresh units arrived to extend the allied positions. Eventually, the line held by Cadogan and Argyll stretched half a mile from Groenewald to another village, Schaerken.

Among the English units pressing the French was the Lord North and Grey’s Regiment, later the 10th Regiment of Foot. With them was Lt. Col. Alexander Spotswood, later a de facto governor of Virginia. Spotswood was wounded and captured during the fighting, but Marlborough negotiated his release after the battle.

Since early in the action, Prince Eugene had been with Marlborough, but the duke detached the prince to take personal command of the right flank. Eighteen newly arrived battalions were sent to support Prince Eugene. Without them, wrote the prince, “I should scarcely have been able to keep my ground.” With the additional manpower, the prince broke through the first line of the enemy. “At the head of the second I found Vendome on foot, a pike in his hand, encouraging the troops,” wrote Prince Eugene. Vendome kept the French in place for a time. General Dubslav Gneomar von Natzmer and his Prussian cavalry hit Vendome’s men, but the French were well protected by the hedges and inflicted heavy losses on the Prussians. As Natzmer’s charge stalled, the Household Cavalry of Louis XIV rushed in and threw back the Prussians.

Vendome inspired the soldiers who saw him leading the resistance to Eugene’s troops, but taking such an intense and personal role in one small portion of the fighting distracted him from the larger battlefield.

In the center, Marlborough directed Dutch and Hanoverian infantry, slowly pushing the French over the Diepenbeek. As the French attacked Marlborough’s line, Private John Marshall Deane of the Foot Guards wrote, “The fight was very desperate on both sides … in which time the enemy was beat from hedge to hedge and breastwork to breastwork … getting them into villages and possessing themselves of houses and making every quicksett hedge a slight wall.” In a similar vein, Sergeant John Miller of the Royal Irish Regiment wrote, “We drove the Enemy from Ditch to Ditch, and Hedge to Hedge, and out of one Scrub to another, and Wood, in great Hurry, Disorder, and Confusion.”

Delayed by the collapse of a temporary bridge, Dutch Marshal Hendrik van Nassau-Ouwerkerk finally joined the allied army at about 6 pm. Known as Lord Overkirk to the English, this cousin of the deceased King William III was the illegitimate son of the Prince of Orange. Overkirk’s London townhouse is now incorporated into the British prime minister’s home at 10 Downing Street.

With Overkirk were 20 battalions of Danish and Dutch infantry, as well as 12 squadrons of Danish cavalry under Claude Frederic T’Serclaes, Count of Tilly. Marlborough had plans for the newly arrived troops. The French south of the Norken were packed into a formation roughly resembling a horseshoe, bound on three sides by the Marollebeek and Diepenbeek, with the open end facing west toward the high ground of the undefended Boser Couter. Overkirk led his horse and foot soldiers behind the hill. Then, part of his force struck the French right flank, while Tilly led the cavalry around the French to come down from the north, onto their left. Meanwhile, Marlborough and Prince Eugene kept up pressure from the south and the east.

One lucky break fell to the French when an allied courier delivered orders to a unit of scarlet-coated soldiers. Mistaken for British redcoats, the men instead were of the Maison du Roi, Louis XIV’s equivalent of the British Household Cavalry and Foot Guards. Knowing of some of Marlborough’s and Eugene’s impending moves, though, simply reinforced the growing certainty that the day was lost.

Beset from all sides and running low on ammunition, one French unit after another broke up. Vendome tried in vain to rally his men and bring up reinforcements. But the reinforcements came under a flanking fire from Cadogan. The fresh battalions accomplished little except to intensify the chaos by further jamming the roads crowded with fleeing soldiers.

Vendome and Burgundy met for an emergency parley at the village of Huisse, north of the Norken. A famous chronicler of Louis XIV’s court, Louis de Rouvroy, Duke of Saint-Simon, recorded what he heard of the meeting. When the Duke of Burgundy began to speak, Vendome’s temper boiled over, and he silenced the royal. The older duke was for holding on at the Norken. After all, half their units had not been in the battle at all. They were in fine shape, he insisted, for reversing their ill fortune by giving battle the next day. No other generals backed Vendome. “Very well, gentlemen,” he said. “I see clearly that you all wish it.” His final shot was saved for Burgundy. “So, we must retreat. And you, Monseigneur, have long desired it.”

The two sides continued fighting until nightfall. Dusk saved the French from a worse catastrophe. “Another hour of daylight would have enabled me to finish the war,” Marlborough later wrote.

Little could be seen of the enemy other than bright musket flashes blazing in the gloom. Overkirk’s men pressing in from the west encountered Prince Eugene’s battalions pushing from the east. In the confusion, many soldiers took friends for foes. John Dalrymple, Earl of Stair, saw two units level their weapons at each other and open fire. When the earl realized that both units were from his own army, he galloped between them and ordered them to cease fire.

A great portion of the French troops trapped between the Marollebeek and the Diepenbeek were surrounded and captured. So many soldiers were ready to surrender that the victors were overwhelmed. Many a potential prisoner took advantage of the confusion and escaped from the battlefield

After the allies ceased fire, a ruse netted hundreds more prisoners. Prince Eugene’s drummers pounded the French call for assembly. Accompanied by the drummers, exiled Huguenot officers shouted the rallying cries of individual French regiments. Stragglers stumbled through the dark toward familiar shouts such as “A moi, Picardie!” or “A moi, Roussillon!” only to step into captivity.

More than 7,000 French became prisoners of the allies, while their killed and wounded numbered another 6,000. The allies also captured 4,500 horses and 100 colors.

By comparison, the allies suffered only about 3,000 casualties: 824 killed and 2,148 wounded, according to a contemporary estimate. Roughly half the allied casualties were among the Dutch. British losses by one estimate ran to 53 officers and men dead and 177 wounded. Casualty totals among the Danish, Prussian, and Hanoverian contingents were each higher than those of the British.

Priests of the parishes surrounding the battlefield buried more than 2,000 slain soldiers after the battle. Hundreds of wounded from both sides lay all night on the field. Prince-Elector George hurried back to the spot where von Losecke fell and was told he had been taken to a house nearby. The colonel died the next day, and as a tribute to him the prince granted his family a pension.

After a 15-mile forced march and a pitched battle, English, German, Dutch, and Danish soldiers bedded down for the night. “The main Body of our Army lay on their Arms very alert all Night, in a very soaking rain,” wrote Sergeant John Millner of the Royal Irish Regiment.

The Marquis of Biron was among numerous high-ranking officers who were wounded or captured. Like many of the other prominent prisoners, Biron was on friendly terms with Marlborough and other English and allied officers. During the Third Anglo-Dutch War of 1672-1674, France and England had been allies. Biron was invited to dine with his old acquaintance, Marlborough. The English commander asked about “the Prince of Wales,” meaning the “Pretender” James. Biron replied that the prince was known in his army as the Chevalier St. George and spoke highly of him. England was still wary of Jacobite intrigues, and Marlborough expressed a warm enough interest in the prince to inspire political gossip in London.

Following Oudenarde, Marlborough invaded France and took Lille after a long siege. Ghent and Bruges fell under allied control once again. Together, Marlborough and Prince Eugene won another victory at Malplaquet in 1709, but the battle’s horrendous toll eroded British support for the war. Vendome, for his part, endured much blame from Burgundy’s friends at court for the loss at Oudenarde. Entrusted with a command again in 1710, his victory at Villaviciosa in Spain revived the fortunes of the Spanish Hapsburgs.

The War of the Spanish Succession ground to a halt with negotiated settlements in 1713-1714. Philip, Duke of Anjou, was confirmed by all parties as King Philip V of Spain. To preserve Europe’s balance of power, Philip renounced any claim on the French throne.

Prince George of Hanover always remembered the smell of powder at Oudenarde. In 1714, upon the death of Queen Anne, his father was the nearest eligible (that is, Protestant) heir to the British throne. The Elector of Hanover was installed as King George I. His son, the veteran of Oudenarde, ascended to the throne in 1727 as George II. On special occasions the king would always call for his “Oudenarde sword.”

After years of repeating his war stories, George II would one day return to the battlefield. During the War of the Austrian Succession in 1743, he took part in the Battle of Dettingen and became the last reigning British monarch to lead soldiers in action.

Thanks for this. Although the Duke of Marlborough and Eugene’s victories are relatively well known the latter, early Georgian period, is not high on the agenda in the UK and so the knowledge that (the later) George 2nd fought at Oudenarde was news to me.

Excellent article.