By Joshua Shepherd

The regiment of Yankees, which was largely composed of German immigrants, advanced through a field of clover in the Shenandoah Valley in search of the Rebel line to its front on June 8, 1862. Its advance was watched closely by three regiments of Confederate soldiers lying prone behind a rail fence on a ridge crowned with timber to their south.

As they crossed the narrow ravine directly beneath the ridge, the 500 men of the 8th New York disappeared momentarily from view. Not only were the enlisted men of the Yankee regiment as green as early summer corn, but so were their field officers. The officers had failed to throw forward a line of skirmishers and mistook the handful of Rebel skirmishers that fell back in front of them as a few isolated, retreating foe.

When the Yankees crested the ridge in perfect alignment, approximately 1,300 Rebels, nearly an entire brigade, were concealed 50 yards away. The Rebels rose quickly to their feet to fire and unleashed a devastating volley. The tremendous crash of musketry felled scores of Federals in seconds. Even the Rebels were shocked by the lopsided bloodshed. “The dead and wounded Yankees were lying on the field as thick as black birds,” wrote Sidney Richardson of the 21st Georgia.

In moments the shattered remnants of the 8th New York streamed in confusion back across the ravine, having lost half their number. The Rebels gave chase, but there was no reason since the unfortunate regiment was in full retreat.

The way the Confederates exploited the Union regiment’s lack of experience had much to do with the success of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson during his famous Valley Campaign of 1862. Although outnumbered in the Shenandoah, Jackson and his men frequently enjoyed tactical advantages because of the skill exhibited by the commanding general and his talented subordinate commanders.

In a whirlwind offensive that spring, Jackson had operated with relative impunity. After suffering his own disappointing reverse at Kernstown, just south of Winchester, on March 23, Jackson campaigned with a vengeance, repeatedly besting Federal troops in unexpected attacks across a wide extent of the Shenandoah Valley. For the Lincoln administration, it was an embarrassing debacle. Frantic that Confederate troops in the Shenandoah might be poised for a strike on Washington, the Union high command funneled an increasing number of reinforcements into the area.

It was exactly as Jackson wished. Under orders to relieve pressure on the Confederate capital at Richmond, which was targeted by the Federal Army of the Potomac, Jackson succeeded in tying up enemy resources in the Shenandoah Valley. Although the shuffling of Federal troops into the valley constituted a strategic gain for the beleaguered Confederate capital, it was nonetheless a double-edged sword for Jackson and his army, tasked with guarding the Confederacy’s Department of the Valley. Jackson succeeded in scoring a major victory at Winchester on May 25, soundly trouncing a Federal corps under the command of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks. The hunter, however, soon found himself the hunted.

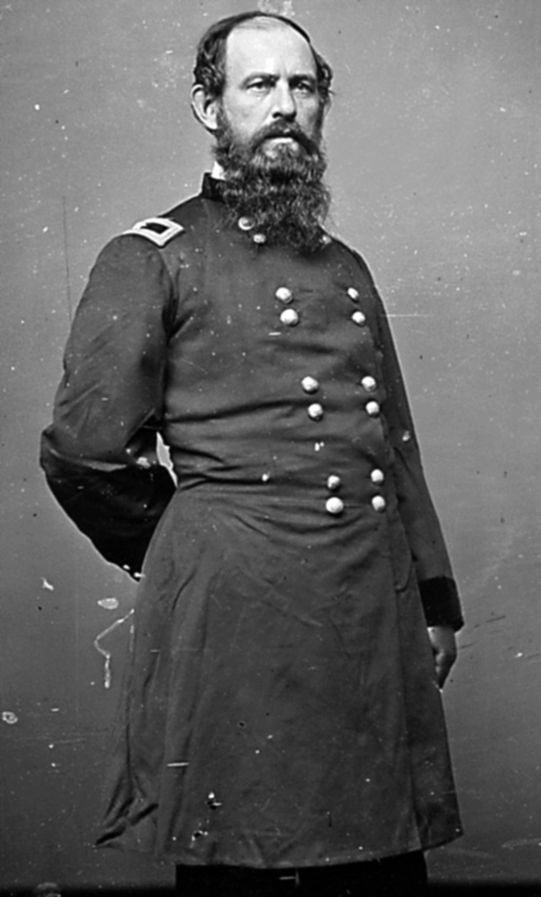

Exasperated by the elusive Jackson’s continued marauding, Lincoln ordered an overwhelming concentration of force to secure the Shenandoah Valley and trap Jackson. While Banks would menace the Rebels from the north, two divisions under Brig. Gen. James Shields would enter the valley from the east. Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont, operating west of the Shenandoah, would move his army into the valley and occupy Harrisonburg, Virginia, directly on the Confederate line of retreat. It was a sensible plan. Unfortunately for Lincoln, his field commanders proved discouragingly feeble. Fremont, rather than head directly east toward Jackson’s supply lines, opted to swing farther north. Shields, who seized Front Royal with his division, was leery of moving farther until he was reinforced. Banks, fecklessly citing the chaotic state of his demoralized command, simply sat tight north of the Potomac and refused to budge.

By June 1, Jackson succeeded in edging past Shields. A desperate foot race ensued, and Jackson made the most of the valley’s geography. The lower valley is bisected by Massanutten Mountain, a 60-mile ridgeline passable at a single locale, New Market Gap. While Confederates raced up the Valley Pike, Fremont advanced on their rear. Shields, who moved up the Luray Valley on the eastern flank of the Massanutten, was unable to effect a linkup with Fremont. Jackson, who was driving his men hard, had ordered out a cavalry detachment that burned two key bridges commanding the approaches to New Market Gap. As the Federal pincer began to close around the southern end of Massanutten Mountain, Shields was certain the game was up, exuberantly writing to Fremont, “I think Jackson is caught this time.”

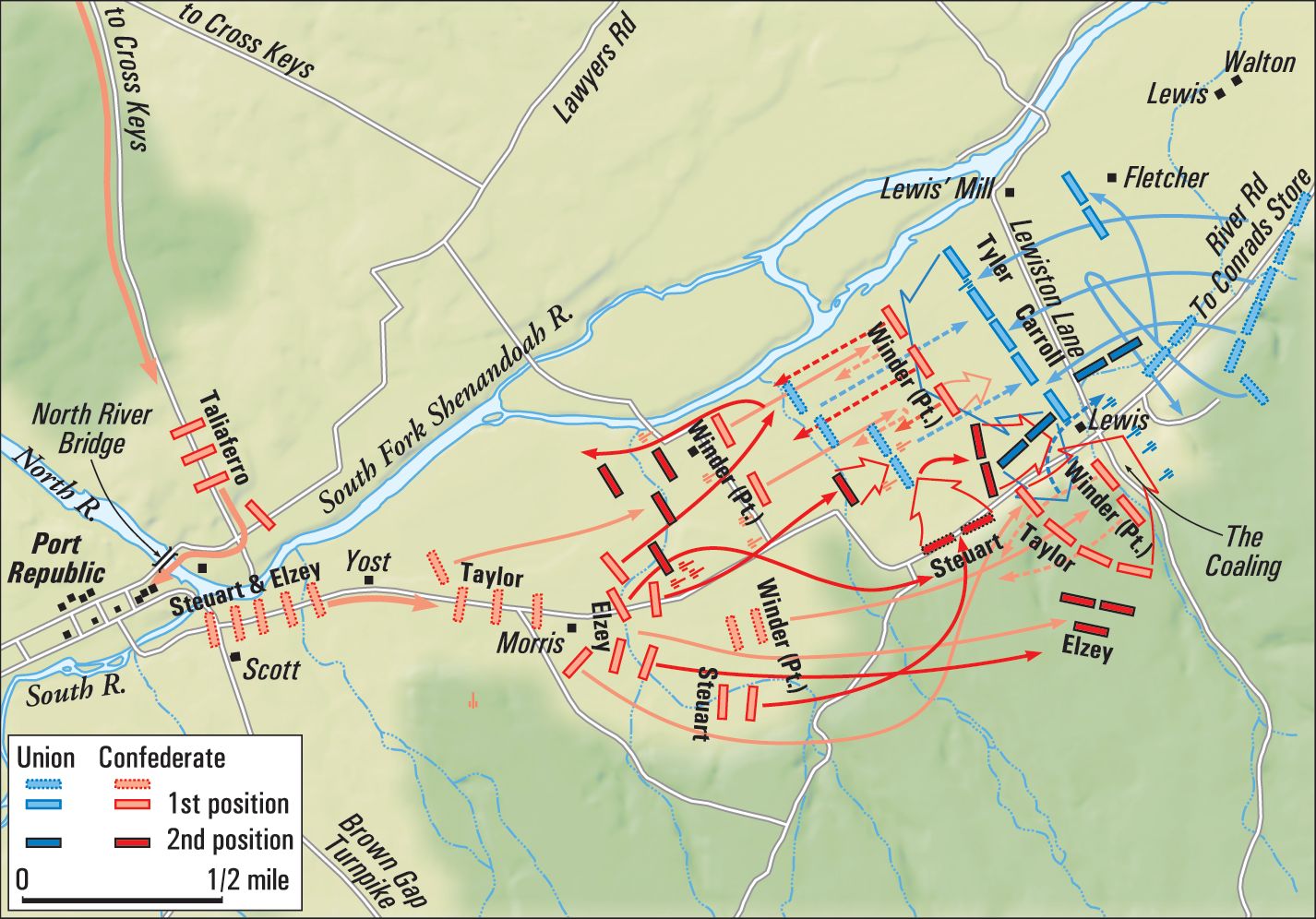

Jackson entertained other ideas. By June 6, he had established his headquarters at the hamlet of Port Republic. The village sat at the confluence of the South River and the North River, which join to form the South Fork of the Shenandoah. By controlling the bridges and fords at the vital confluence, Jackson could continue to deny direct cooperation between Fremont and Shields. To block Fremont’s advance, Stonewall posted a division under Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell five miles north at Cross Keys Tavern. Confederate horsemen operating near Harrisonburg sparred with Fremont’s vanguard, and Jackson’s charismatic cavalry chief, Brig. Gen. Turner Ashby, was killed. Despite the spirited skirmish, Jackson was beginning to believe that opportunities for offensive action had disappeared. “At present,” he reported, “I do not see that I can do much more than rest my command.”

Two days later, such a conclusion proved erroneous. The pious Jackson looked forward to Sunday, June 8, as a quiet opportunity for divine worship. Confederate cavalry, however, in a good bit of disarray in the wake of Ashby’s death, failed to give timely warning that Yankee cavalry was riding hard for Port Republic. Ironically, the 150 troopers were from the Unionist 1st Virginia Cavalry. At about 8:30 am, the Federals splashed across the South River into Port Republic, which was held by just three companies; the bulk of Jackson’s army was camped across the North River. Stonewall, who spent the night in town with his staff, had just a few moments notice of the impending raid.

While the Federals thundered through the streets rounding up prisoners, Jackson barely escaped over the North River Bridge. The raiders made for the army’s supply wagons south of town but ran into an ambush orchestrated by a doughty company commander, Captain Samuel Moore. Jackson rallied his infantry across the river, and when Confederate troops swarmed over the bridge the horsemen fled the village in a good bit of confusion. For a chagrined Jackson, it had been an inauspicious morning.

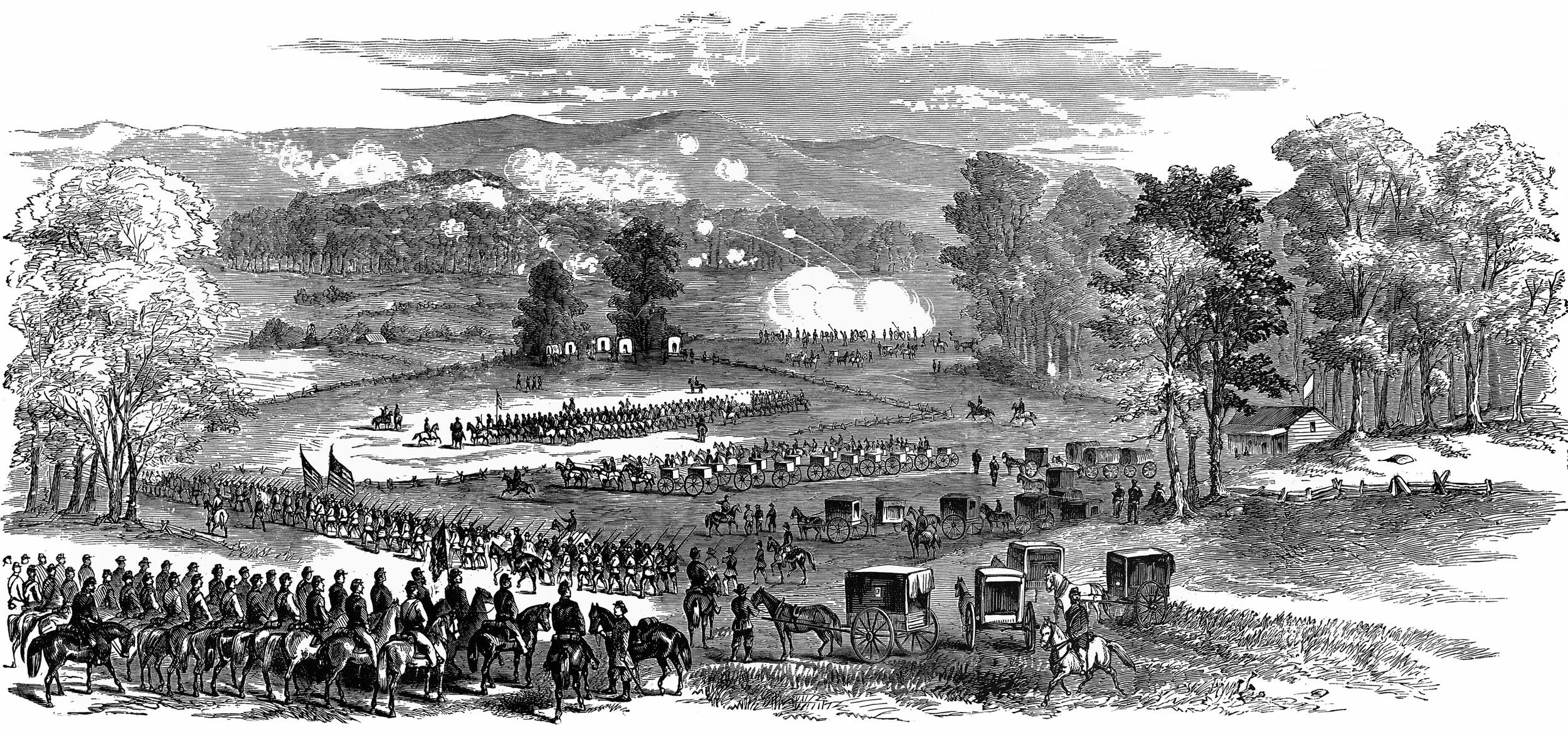

While Jackson solidified his grip on Port Republic, the situation west of town presented potential disaster. At daybreak, Fremont had his army on the move from Harrisonburg and embarked on a collision course with Ewell’s division at Cross Keys. Known by the grandiose sobriquet “Pathfinder” for his legendary explorations of the Rocky Mountain West, Fremont had seven brigades at his disposal, roughly 10,500 men, itching for a chance to bring the elusive Rebels to bay. Only Ewell, with three brigades and some 5,000 men, blocked the Federal advance on Jackson’s rear.

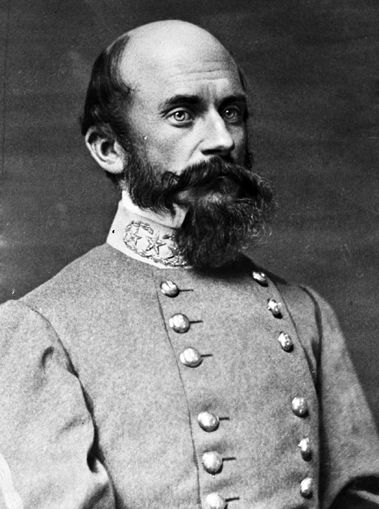

Notwithstanding his decided numerical advantage, Fremont faced tough opposition. Endowed with pop eyes and a dramatically receding hairline, Ewell had earned the unflattering sobriquet “Old Bald Head” from his waggish troops. But despite an eccentric appearance, Ewell was a thoroughgoing soldier. A West Point graduate and respected Mexican War veteran, Ewell was regarded as a tough fighter who knew his business. Perhaps more importantly, he had chosen his ground well, deploying his troops on a formidable ridgeline a mile south of Cross Keys. The position was ready made for an energetic defender. “A valley and rivulet in my front,” reported a delighted Ewell, “woods on both flanks, and a field of some hundreds of acres where the road crossed the center of my line.”

Fremont, however, gave little serious thought to maneuver and ordered his men into line of battle across the open ground in Ewell’s front. At about 10 am, the artillery opened up. For jittery troops on both sides, it was a deafening overture. From their stronghold atop the ridge, Confederate gunners played havoc with Fremont’s crouching infantry and engaged in spirited counterbattery fire with their Federal opponents. For nearly an hour the big guns slugged it out, shaking the valley with an incessant rumble. It was, thought Federal Colonel Albert Tracy, a “positive roar.”

Brigadier General Julius Stahel’s brigade began the Union attack. The 1,300 Confederates who had shattered Colonel Francis Wutschel’s 8th New York belonged to Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s Brigade. Their unfortunate foe had constituted the far left of the Union line.

Trimble, far from resting on his laurels in the aftermath of the repulse of the 8th New York, was eager to hammer the disorganized Federals. He soon had his eye on Yankee artillery across the valley, the Unionist Virginia battery of Captain Frank Buell.

Trimble ordered a portion of the 15th Alabama to execute a wide swing around the Federal left and then fall on the enemy flank. Led by Lt. Col. John Treutlen, the Alabamians gamely charged the position but ran into unexpected resistance. In addition to Buell’s guns, the hill was held by elements of the 27th Pennsylvania and a crack outfit of Pennsylvania riflemen, the Bucktails, who stubbornly contested the ground. After a bloody exchange of gunfire, Treutlen was forced to pull his men back to regroup.

The Pennsylvanians, however, were soon assailed by Trimble’s other two regiments. The 16th Mississippi drove into the center of the hill and suffered heavily from enfilading musketry emanating from the 27th Pennsylvania; the Mississippians’ commander, Colonel Carnot Posey, was badly wounded and carried to the rear. The stalemate was broken by the 21st Georgia, which crashed into the Pennsylvanians and unhinged the Federal position. Union troops fled for the rear in some disorder but had given a good accounting of themselves. Their bravery, thought Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy, “was evidenced by the number of dead rebels” strewn on the hillside.

Trimble’s blood was clearly up, and he was eager to maintain his momentum by keeping up pressure on the enemy. His next target was another Federal line stretched across two hillocks near the homestead of farmer George Evers. The position was a stout one, occupied by the Federal brigade of Brig. Gen. Henry Bohlen, who commanded four regiments of New York and Pennsylvania volunteers. Bohlen’s brigade stood in support of two New York batteries commanded by Captains Louis Schirmer and Michael Wiedrich.

The Confederates would face a tough fight at the Evers farm. Trimble, personally leading half of the 15th Alabama, swung around to the right; the rest of his brigade was regrouping from their previous attacks. He had help in the form of two Virginia regiments, the 25th and 13th, under the command of Colonel James Walker. Coming in on Trimble’s right, the Virginians were subjected to a punishing fire. Musketry swept their ranks, and Wiedrich’s artillery switched to canister. Stalled but by no means willing to give up the fight, Walker took up positions behind a rail fence and traded fire with the Federals on the hill. With the Yankees thus occupied, Trimble readied his Alabamians for a final push that he was certain would smash Bohlen.

He was only partly correct. The Federal position was disintegrating largely due to an unfortunate disagreement in the officer corps. Although Wiedrich’s battery had driven back the enemy with heavy casualties, the artillerymen were abruptly ordered from the field by Schirmer. Bohlen and Wiedrich protested the move but were overruled in a bizarre arrangement, which left Schirmer, the senior artillery officer on the scene, with the final word. As Wiedrich pulled out, Federal infantry followed suit, and Trimble’s final drive to secure the hill was somewhat uncontested.

Fremont was quickly losing interest in the fight altogether. After Trimble had battered in his left for roughly a mile, the general opted to pull in that flank and press forward the rest of his line. His prosecution of the attack was perfunctory at best. Milroy, commanding in the center, was game enough for a fight but had little support as he approached the formidable enemy position on the ridge. Confederate artillery subjected his men to a fearful barrage as they came forward, and Milroy attempted to gain a modicum of cover in a shallow ravine. It afforded only a momentary respite. As soon as Milroy’s troops approached a second ravine, recalled the general, “We discovered it was full of [Rebels] lying behind a fence in the tall grass almost wholly concealed from view.”

The results of the surprise were predictable. Milroy’s lead troops were shot down, and the demoralized Federals, firing blindly at an enemy they could not see, became hopelessly stalled. Milroy angled toward his right front but fared no better in further attempts. He again ran into woods full of Rebels. “A deadly fire came out of it,” wrote a dismayed Milroy, “and my boys were dropped by it rapidly.”

The expected support to his right, Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck’s outfit, was a virtual no-show that left Milroy’s troops to bear the brunt of Confederate attention. Schenck led a ponderous brigade of five Ohio regiments backed up by two batteries, but the politician-turned-general had only the vaguest notion of how to use them. Colonel Albert Tracy of Fremont’s staff disgustedly reported that while Milroy’s brigade was being chewed up Schenck made a lukewarm approach on the Confederate right, which he merely “brushed with emphasis.”

With that, the Federal offensive at Cross Keys, such as it was, fizzled out in anticlimax. Alarmed that his troops had faced a real fight from an enemy half their strength, Fremont was content to pull back and assume the defensive. Ewell characteristically moved forward and occupied the surrendered ground. In thinly veiled contempt for his opponent’s tactical bumbling, “Old Bald Head” caustically observed that “he felt all day as though he were again fighting the feeble, semi-civilized armies of Mexico.”

Back in Port Republic, the encouraging news of the victory proved crucial as Jackson planned his next move. Following the embarrassing dustup with Federal cavalry that morning, Jackson was eager to pounce on the exposed lead elements of Shields’s column northeast of town. With a passive Fremont clearly on his heels at Cross Keys, Jackson was free to take advantage of the situation. Jackson decided to throw his full weight at Shields rather than Fremont because Shields was nearly begging to be attacked, explained Jackson afterward. His force was smaller, badly straggling, and his line of retreat lay over poor roads. Most importantly, Shields’s isolated vanguard, under the command of Brig. Gen. Erastus Tyler, was invitingly positioned just two miles from Port Republic.

Jackson wasted little time making his move. His first order of business was concentrating his forces for the proposed attack. Stonewall was pleased with the outcome of the fight at Cross Keys and eventually issued orders for a token holding force to contest the ground in front of Fremont while the bulk of Ewell’s division slipped away for the combined blow against Tyler. The rearguard duty fell to Trimble, a static task for which he was poorly suited. It was all that Jackson and Ewell could do to keep the impetuous brigadier from attacking the Yankees single handed.

Jackson would have little rest that night. In addition to organizing the consolidation of his army, Jackson ordered a last minute fix to the very real obstacle of getting his infantry over the South River. An engineering outfit undertook the construction of a makeshift bridge but had little time for such a daunting task. The crew wrestled six wagons into the river and filled them with stones to serve as makeshift piers. The wagon beds were finally spanned by lumber hastily scrounged from a local sawmill, but the pioneers ran short of planks. After a few hours of backbreaking labor the bridge was completed. The bridge was serviceable but far less sturdy than desired.

Confederate troops, who had no idea what Stonewall had in store for them, were on the move before daybreak. At Cross Keys the men of the 13th Virginia, who had not eaten all day on June 8, began cooking a belated meal at 3 am. They would be sorely disappointed again. “Boys, I am sorry for you,” Ewell announced, “but you have to put your utensils back as we have to march at once.” Senior officers were equally in the dark. Brig. Gen. Charles Winder was awakened at 3:45 am with orders from Jackson that clearly meant a fight was in the offing. Winder was to have his brigade in Port Republic within the hour.

About sunrise the troops began crossing the South River before turning north toward the Yankees. The river crossing, however, proved a fiasco from the outset. The results of moving thousands of armed men over a few rickety boards were predictable. While artillery batteries forded the river, infantry moving over the improvised foot bridge found that the crossing quickly degenerated to a precarious trapeze act. Due to the bottleneck at the river, Confederate troops would necessarily be thrown piecemeal into the fight.

The unenviable task of launching the attack was assigned to Jackson’s old outfit, the legendary Stonewall Brigade. The general still regarded the unit as one of his very best, and it was ably led by Winder. Trained at West Point and blooded on the Western frontier, Winder combined unimpeachable personal bravery with rock solid dependability. Alarmed by his superior’s penchant for risk taking and hard marching, Winder at one time referred to Jackson as insane. But in spite of the personality clash, the brigadier could be counted on to execute his orders with cool and deliberate judgment. At about 7 am, Winder made contact with the enemy.

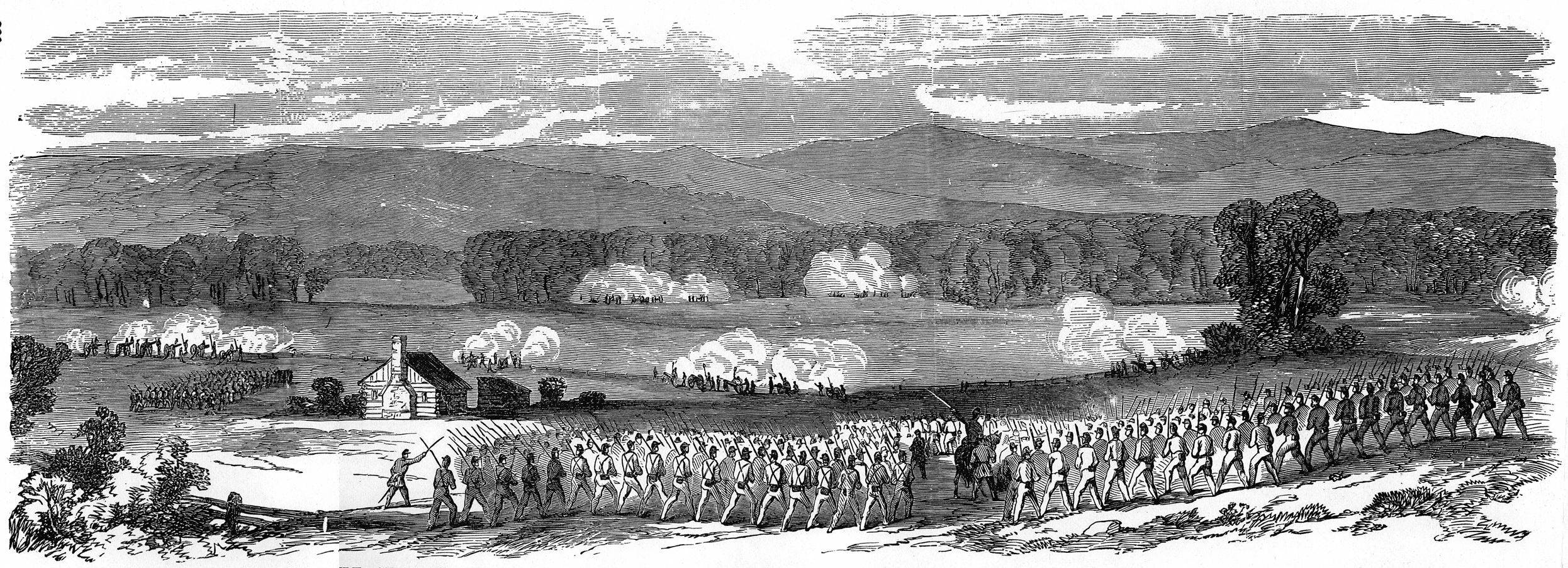

A skirmish line drawn from Colonel James W. Allen’s 2nd Virginia quickly brushed aside a thin screen of Federal pickets. It became apparent, however, that stiffer resistance lay ahead. In front of the Confederates lay several miles of farmland that stretched along the Shenandoah River’s south fork. The ground was primarily worked by the Baugher and Lewis families, who carved a comfortable living from the fertile bottomlands. Largely planted in wheat, the fields, laced by farm lanes and rail fences, afforded little cover.

Worse yet, topography afforded a decided advantage to the Federals, and Tyler would enjoy a position of considerable strength. As Confederate troops came into view, he calmly held his men under cover near the Lewis homestead. The Confederate advance, which would come across open ground, was hemmed in by the river on the left. More ominously, the Federal left rested on a prominent knob that commanded the entire field. The Lewis family had leveled the site for a charcoal-burning operation that supplied the needs of the farm, rendering the site an ideal artillery platform. Tyler valued the spot for its abrupt elevation, an imposing 90 feet above the valley floor, and had six guns situated there. The locale would soon be enshrined in the American military lexicon as the scene of some of the most savage fighting of the war: the Coaling.

Jackson immediately grasped that possession of the Coaling carried victory with it and ordered Winder to seize the hill. Winder, however, had only four regiments of the Stonewall Brigade with which to work. The brigadier ordered the 2nd and 4th Virginia to execute a wide flanking maneuver through the woods on the right from which they could assault the Coaling. Captain Joseph Carpenter’s “Allegheny Roughs” Battery was to support their advance. As Carpenter moved forward to occupy the enemy, Winder deployed his remaining two regiments: the 5th Virginia on his left, the 27th on his right. The infantrymen were backed up by the stalwart gunners of the Rockbridge Artillery led by Captain William T. Poague.

Winder initially held his outnumbered infantry in support. The bulk of the Rockbridge Artillery, four guns, were smoothbores that Winder realized would be next to useless in any duel with Federal guns on the Coaling. Poague consequently deployed with just two Parrott rifles, which went into battery in a wheat field next to the Baugher farm lane. They were soon joined by two pieces from Carpenter’s battery, which had gotten nowhere in a failed attempt to work its way through the underbrush off the Confederate right. From the outset, the Confederate attempt to flank the Coaling was deteriorating.

In the face of such uneven odds, Rebel gunners worked their pieces manfully but took a beating in the process. Federal gunners quickly acquired the range and from their elevated perch sent shells plunging through the Confederate crews. For their part, Federal gunners remained largely unscathed, noting that the majority of incoming fire passed harmlessly overhead. Jackson was proud of his artillerists, but he noted that they were outmatched. “The artillery fire was well sustained by our batteries, but found unequal to that of the enemy,” he wrote.

Winder worked his men toward the left in a desperate attempt to gain cover from the cannonade, and the 5th Virginia took up posts adjacent to the Shenandoah. Tyler finally unleashed his own infantry, wheeling left in a broad arc that left his line stretched across the valley floor along the Lewis farm lane; he comfortably anchored his right on the river, his left on the Coaling. It was, though, a somewhat disjointed arrangement. The two-regiment Confederate thrust likewise caused Tyler to split his force, and a yawning gap opened in the center of the Yankee position. The Federal line “was formed in two distinct and unconnected parts,” wrote Captain James Huntington, who commanded Battery H, 1st Ohio Artillery.

Still, the 3,000-strong Union force easily dwarfed Winder’s two regiments, which brought fewer than 600 men into action.

It was a horribly mismatched affair. Winder’s men advanced under fire and held on as best they could. But as the valley floor erupted with sheets of musketry, it likewise became apparent that Federal artillery fire from the right showed no signs of letting up. Much to Winder’s dismay, the planned flank attack of the 2nd and 4th Virginia Regiments against the Coaling ended in an anticlimactic flop. The two regiments had reached a ravine in front of the hill, exchanged a few volleys with its defenders, and summarily fallen back.

For Winder’s beleaguered infantry, the full force of Tyler’s line was simply more than they could bear, and the general pulled back to a safer distance. As Winder regrouped along the Baugher lane, reinforcements arrived on the field. It was Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor’s Louisiana Brigade, a hard-fighting outfit that was one of Jackson’s best brigades. Although attached to Ewell’s division, the Louisianans had missed the action at Cross Keys and were itching for a fight.

The Pelican Staters were a colorful lot. The four-regiment brigade included the Louisiana Tigers, a motley set of New Orleans street toughs who were poorly disciplined but fierce brawlers. The unit was led by Major Roberdeau Wheat, a barrel-chested Army veteran, soldier of fortune, and no-nonsense combat officer. For Jackson, their timely arrival on the field was nothing short of providential, and he immediately directed Taylor to send one of his regiments up in support of Winder and lead the bulk of his brigade to the vortex of the fighting. The Louisianans would assault the Coaling.

Winder’s men were glad to have the help. Under the pressure of a Federal counterthrust, the Rebels were holding on as best they could at the Baugher lane. Winder strengthened the center of his line with Colonel Harry Hays’ 7th Louisiana and rushed forward a battery of horse artillery under the command of Captain R. Preston Chew. As the guns rolled into action, they entered a maelstrom. Enemy fire swept the field, which, recalled artillerist George Neese, was covered with “limping, bleeding, and groaning” men. Winder’s hard-pressed troops were nearly frantic for assistance amid the storm. “Hurry up,” they shouted to the gunners, “they are cutting us all to pieces.”

With his line stabilized, Winder faced a crucial decision. Even after strengthening his line, the position, subjected as it was to a terrible plunging fire from enemy artillery, was a treacherous one. With the Louisiana Brigade on the move for the Coaling, Winder felt compelled to make the most unenviable of tactical judgments by launching his men directly into the Federals. The counterattack was a desperate attempt to distract attention from Taylor’s Louisianans, on whose fortunes the fate of battle obviously rested. The Confederates went forward gamely enough, recalled an admiring Winder, “in gallant style with a cheer.”

Winder’s forlorn counterattack was a grim sacrifice. The Confederates braved a firestorm and suffered horrendous casualties. Guns on the Coaling, thought 7th Louisiana Captain Daniel Wilson, “poured streams of shell and shot, mowing down our men like grass. The earth seemed covered with the dead and wounded.” Union musketry added to the bloodshed, and the three assaulting regiments were badly mauled. Their Federal opponents fared little better. The 7th Indiana on Tyler’s right suffered especially heavy losses as it fought it out with the 5th Virginia. Colonel James Gavin stalked up and down his line of Hoosiers bellowing orders and waving his sword overhead. The common soldier died without such heroics.

Despite taking a toll on their Northern opponents, the Rebels were forced to fall back, and Winder’s scratch brigade rallied behind a rail fence. Sensing victory, Federal infantry lunged forward in a counterattack. As the Northerners sprinted headlong across the wheatfields, the Confederates broke for the rear. Backwoods hunters from the 7th Indiana worked around the left flank of the 5th Virginia and unleashed a galling enfilade fire. Gavin shouted simple orders to his Hoosiers: “Load, charge bayonets, and at them.” It was more than the outnumbered Confederates could bear. The enemy pressed his men so hard, reported Winder, “that it was impossible to rally them.”

Just when all appeared lost, Winder caught a glimpse of two Confederate regiments lying prone well to the front. It was Ewell, fresh on the field after a march from Cross Keys and eager to strike a blow. He had arrived at the head of two regiments, the 44th and 58th Virginia, after swinging through the woods to the right and turning back toward the valley until he was facing the left rear of the charging Federals. He immediately knew what had to be done. Leading a headlong charge into the open, Ewell burst into the Federal rear, delivered a volley at close range, and stalled the Federal advance. But Ewell’s Virginians, who had exposed their own flank by moving forward, paid a dreadful toll for their effort. Federal guns on the Coaling sent shells crashing through their ranks, and the Rebels fell back to the cover of the woods. Despite a continued trickle of Confederate reinforcements, morale flagged after Winder had been so roughly handled. Only the capture of Federal artillery on the Coaling could save Jackson from a crushing defeat.

Right on cue, Taylor’s brigade arrived at the ravine in front of the Coaling just as troops in the valley were on the verge of collapse. The Louisianans were considerably winded after thrashing through tangled underbrush on their circuitous march toward the Federal right and found that they had missed their mark. Far from coming in on the Coaling’s flank, they were facing the muzzles of enemy artillery head on. With little time to waste, Taylor immediately ordered his entire brigade, approximately 1,700 strong, to the attack. “Forward! Charge the battery and take it,” he shouted.

In an instant, the brigade rushed into the ravine and clawed its way up the other side, yelling, thought Neese, “like mad demons.” Startled Federal gunners on the hill frantically redirected their aim into the ravine and let loose with canister. The Louisianans took a fearful beating but could not be stopped. Without pausing to regroup, bayonet-wielding Confederates rushed into the battery, thrusting, clubbing, and cursing with wild abandon. Union artillerists defended their guns with admirable tenacity but were overwhelmed in hellish hand-to-hand fighting. Apprehensive that a Federal counterattack could withdraw the six captured guns, Confederate troops began slaughtering the battery horses.

Such fears were not misplaced. Tyler was able to hastily scrape together three Ohio regiments, the 5th, 7th, and 66th, who were thrown at the Coaling. The Buckeyes came on, recalled Taylor, in “a determined and well conducted advance,” and then pitched into the Rebels in a brutal close quarters fight. Considerably disorganized after their chaotic charge, Taylor’s Louisianans fell back in front of the Union wave.

Horrendous seesaw fighting ensued. Confederates fired on the position while they regrouped and then once again scrambled back up the hill into the midst of its Yankee defenders. The Federals fell back, rallied, and charged again, seizing the summit amid nightmarish fighting that participants would never forget. “Men beat each other’s brains out,” recalled an anonymous Louisianan. “Those who go down to die think only of revenge, and they clutch the nearest foe with a grasp which renders death stronger.”

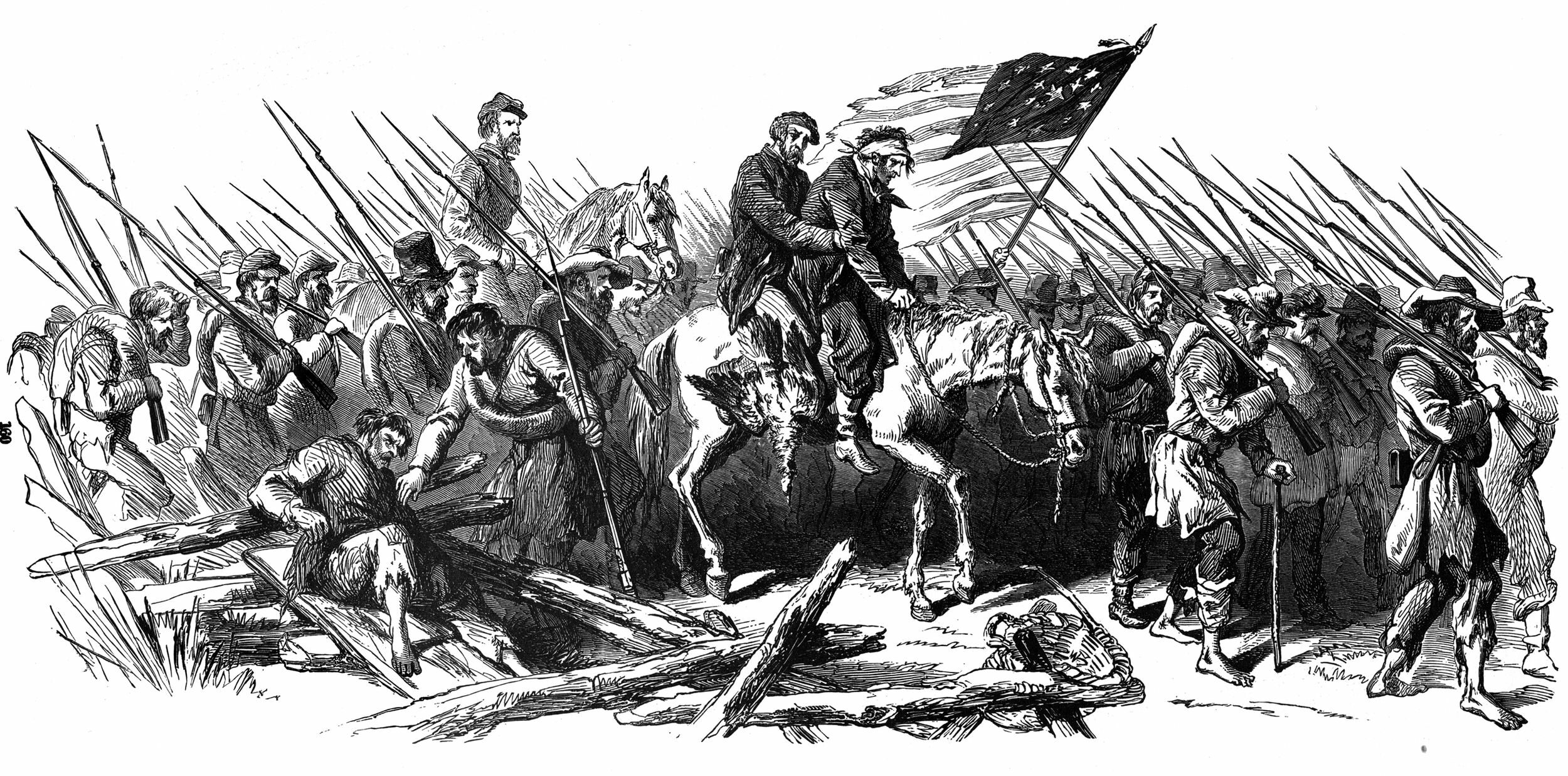

Once again, Ewell showed impeccable timing. Coming up at the head of desperately needed reinforcements, the general threw his weight into the fight. In the midst of savage yelling, the Confederates rallied for a final attempt. Swarming up the hill and into the battery, Rebel troops at last shattered enemy resistance in an impetuous and bloody attack. Federal troops fled the position and succeeded in drawing off just one gun. The scene of the bitter struggle resembled a charnel house. The hillside was littered with dead Confederates, and the summit was heaped with the dead and wounded of both sides, strewn about the guns. In moments, the fortunes of the battle had shifted irrevocably.

With the fall of the Coaling, the Federal line down in the valley began to unravel. Tyler issued orders for a general withdrawal, and although some of his troops put up a running fight, the retreat eventually degenerated into a chaotic rout. Sensing that a total victory was within grasp, Jackson rode to the front and ordered his entire line forward. The Rebels “threw the rear of our column in great disorder,” recalled Federal Colonel Samuel Carroll. It was a miraculous and sudden turn of events. Confederate troops who had been taking a grim beating all day rushed forward on the heels of the retreating Federals, and Jackson hurriedly sent up reinforcements that were arriving on the field. With the Yankees on the run, an exuberant Jackson was clearly in his element. “He who cannot see the hand of God in this is blind sir, blind,” Jackson said to Ewell.

For Tyler, it was an utter disaster. Confederates pursued his demoralized troops for miles, snatching up stragglers by the dozen. After the battle had ended in catastrophe and his presence on the scene was nearly pointless, Fremont at last stumbled his way onto the hills overlooking the battlefield. His approach had been quite leisurely. Rather than threatening Jackson’s rear, the Pathfinder had simply inched his way forward. By the time he arrived at Port Republic, Fremont was, naturally, stranded on the north side of the river; Confederate troops, who had ample time to get out of his way, had burned the North River Bridge. The Pathfinder then made one of the most pathetically impotent gestures of the war. Unlimbering his artillery on the heights overlooking the river, Fremont commenced shelling the battlefield, where ambulance crews, as well as the wounded of both sides, desperately scrambled for cover.

For his part, Jackson had no further desire to meddle with either Fremont or Shields, both of whom had been largely emasculated during the fighting of the previous two days. By the following morning, Jackson’s troops had drawn off and were safely tucked away in the upper reaches of Brown’s Gap in the Blue Ridge. After their lackluster performances, both Federal commanders received orders to fall back. Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell explained that Shields’s troops were needed for the campaign against Richmond, and it was “not considered expedient to continue the chase.” Exactly whom had been chasing who during the Valley Campaign was likely an inscrutable mystery to the Lincoln administration.

Jackson’s stunning twin victory came at a heavy price, and the ghastly human wreckage that littered the battlefield belied any pretenses to martial glory. Confederate losses for the two days amounted to roughly 1,200 overall, including 239 killed. Federal forces had suffered even greater losses: 272 killed and 1,600 wounded and missing. Even the unflappable Jackson was shocked by the carnage. “I never saw so many dead in such a small space in all my life,” he wrote.

The strategic magnitude of the Federal repulses at Cross Keys and Port Republic became readily apparent in the coming weeks. Jackson, having thrashed every Federal command in the Shenandoah, was at liberty to transport his troops to Richmond where, during the last week of June, the swelled ranks of the Army of Northern Virginia would triumph in the Seven Days’ Battles, an epic contest that eliminated the Union threat to the Confederate capital. Jackson’s Valley Campaign, one of the most legendary exploits in American military history, ensured that the fertile Shenandoah Valley would largely remain free of Federal incursions for the succeeding two years.

Lionized as a military genius in the Southern press, Jackson was ensured a place in the pantheon of Confederate legends. The deeply religious Jackson explained the stunning close to the Valley Campaign in far different terms. “God has been our shield,” he wrote, “and to His name be all the glory.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments