By Eric Niderost

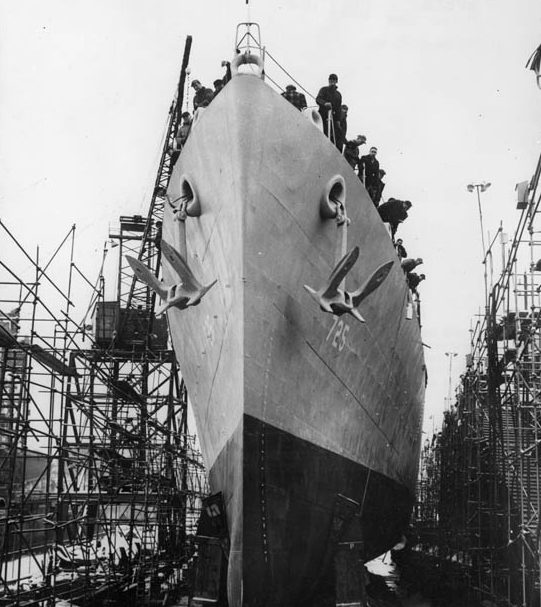

At exactly three o’clock in the afternoon on February 25, 1944, a crowd gathered at the Boston Navy Yard for the commissioning ceremony of the USS O’Brien (DD725), a destroyer of the Sumner class. Built by Bath Iron Works of Bath, Maine, and named after Captain Jeremiah O’Brien, a U.S. naval officer of Revolutionary War fame, the destroyer had been launched on July 12, 1943, and, after the usual fitting out, a skeleton crew sailed her down to Boston.

The ceremony was impressive, with military protocol and tradition strictly observed. Commander P.F. Heerbrandt, the designated skipper of the new ship, was handed its new ensign, which was hoisted after the usual preliminaries. As the flag unfurled in the chilly winter breeze, the officers turned and smartly saluted.

The crew was lined up on the dock, ready to come aboard, when the signal was given to man the ship. The group of civilians stood just above on a high platform, bundled up against the New England chill. They were mainly wives and other relatives of the ship’s crew, there to witness the historic moment.

World War II was raging in both Europe and the Pacific, and commissioning ceremonies were commonplace in a time of global conflict. But the O’Brien, fresh from the builder’s yard, was to earn a particularly distinguished record in the months to come. The destroyer served in so many theaters and so many climes that some of the record seems to have been obscured by time or forgotten altogether.

But to “plank men”—those who served aboard the ship from the very first day––every moment is indelibly etched in their memories. One such is Ray Woods, who was senior radarman on the O’Brien from its commissioning to the end of its service in World War II.

Developed by the British in the 1930s, radar was a key factor in the 1940 defeat of the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain. The technology was not only new, it was secret, at least to the public at large. “We were told,” Woods recalled, “that if asked what our rating badge meant, we were to say ‘Radioman.’”

After the commissioning ceremony, the friends and relatives were allowed to come aboard for a tour. There was only one area that was off limits—the radar room.

The USS O’Brien was a magnificent warship, fast, maneuverable, and well armed. She was equipped with a half dozen 5-inch/38-caliber guns, two twin and two quadruple 40mm antiaircraft mounts, and two quintuple 21-inch deck torpedo tubes. If necessary, the ship could reach a maximum speed of 34.5 knots, at least on paper.

The O’Brien Prepares for D-Day

After the O’Brien’s commissioning, the skipper took her out on a shakedown cruise. Drills were conducted, and the crew became more and more like a functioning team. Much of the shakedown was held in the waters off Bermuda, then it was back to Boston to await further orders. They were not long in coming. The O’Brien would be part of Destroyer Division 119, which included the USS Barton (DD772), USS Walke (DD723), USS Laffey (DD724), and USS Meredith (DD726).

For their maiden voyage, the O’Brien and her companion vessels escorted eight ammunition-laden ships across the Atlantic without incident. Commander Robert Montgomery, a major Hollywood celebrity who had given up stardom to join the war effort, served aboard the O’Brien at this time, and Woods remembered him as a flag officer in the radar room. After the war, Montgomery went back to acting and starred in director John Ford’s 1945 tribute to the PT-boats, They Were Expendable.

After a stop at Belfast, Northern Ireland, the ship headed to England and ended up at Plymouth. The harbor at Plymouth, where the Pilgrims once set sail for America in 1620, was crowded with warships of every description, and barrage balloons floated over the ancient city like they did through most of Britain. It was said in jest that so many men and so much equipment were on the island, preparing for the invasion of France, only the barrage balloons kept it from sinking into the sea.

It was the spring of 1944, and by May the sense of anticipation was growing. Everyone knew that Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of German-occupied France, was about to begin—but no one knew when. The time and place of the invasion were one of the most closely guarded secrets of World War II.

To counter the expected Allied assault, the Germans had been building the Atlantic Wall, a series of powerful coastal fortifications, since 1943. Beaches were mined and steel beam obstacles—nicknamed “hedgehogs” by the Allies—dotted the sands of the likely invasion beaches. Reinforced concrete pillboxes sheltered machine-gun nests and an array of artillery, including 15-inch guns.

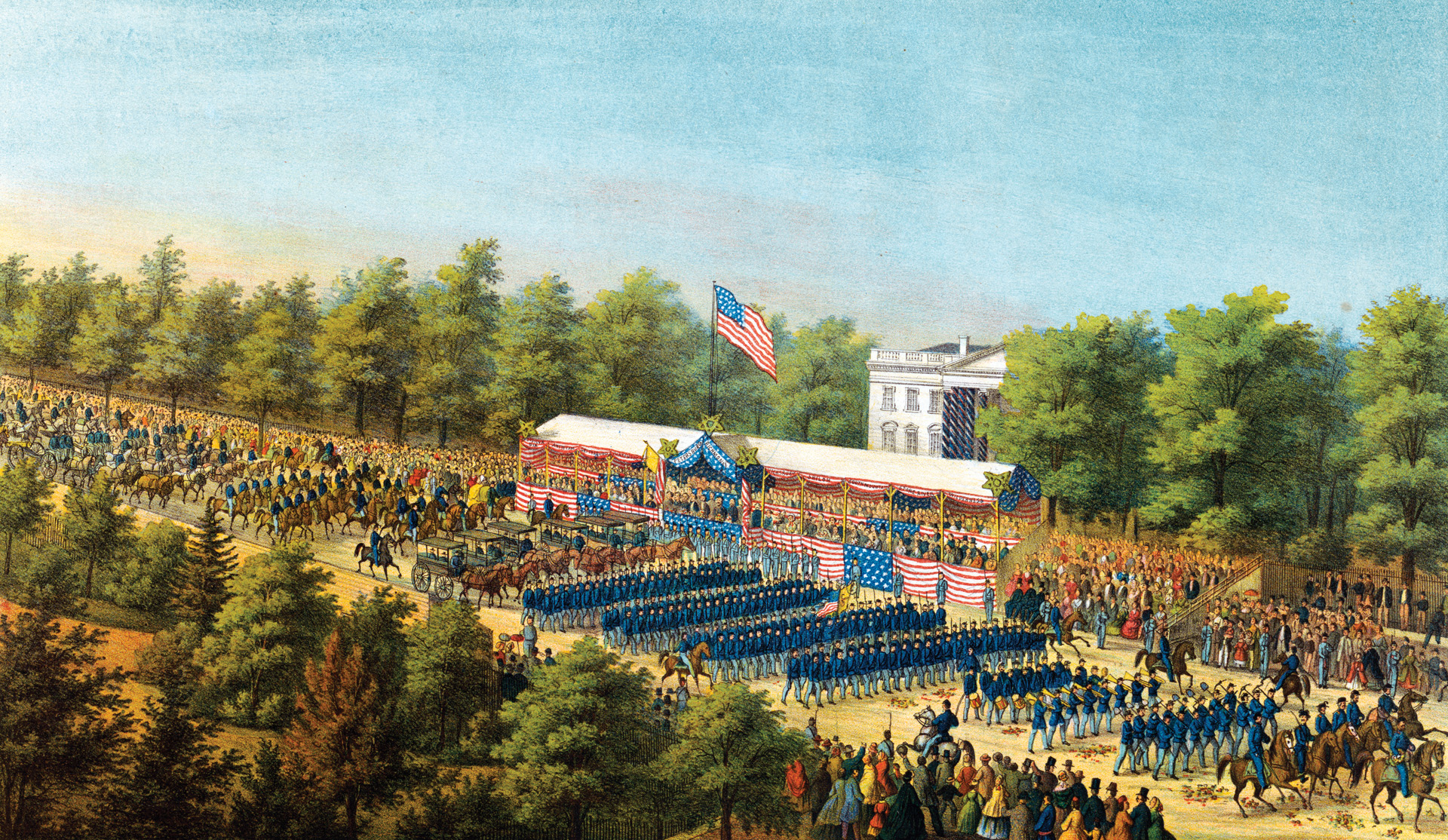

The Allied buildup for D-Day staggers the imagination. There were 39 divisions—20 American, 14 British, three Canadian, one Free French, and one Polish. They would be supported by nearly 11,000 aircraft, including 5,000 fighters, 2,300 transport planes, and 2,600 gliders. The Allied invasion would also be augmented by 6,000 warships, transports, and landing craft.

The coast of Normandy had been selected as the site for the invasion, and five landing beaches were staked out: Utah, Omaha, Juno, Gold, and Sword. Two of the beaches, Omaha and Utah, were assigned to the Americans, while the other three were Anglo-Canadian.

That spring the O’Brien acquired a new captain, Commander William W. Outerbridge. Outerbridge had the distinction of ordering the first shot in the defense of the United States in World War II. Born in Hong Kong in 1906 and having graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1927, the bespectacled officer was in command of the destroyer USS Ward (DD139), an old four-stacker destroyer that was on patrol off the entrance to Pearl Harbor in the early morning hours of December 7, 1941.

When a Japanese midget submarine was spotted trying to gain access to Pearl Harbor, Outerbridge ordered No. 3 deck gun to open fire, and a depth charge run. The submarine was sunk, and Outerbridge was later awarded the Navy Cross. But now Outerbridge faced a new command with a new set of challenges.

Improvised Fire Support on Omaha Beach

Operation Neptune, the assault phase of the Normandy invasion, had battleships, cruisers, and 104 destroyers—the O’Brien included—forming a bombardment force to support the amphibious landings. The ships were to engage the German coastal batteries and provide general covering fire for the landing craft and their occupants.

Originally the ships supporting the operation were to leave port on June 5, 1944, and, accordingly, the O’Brien left England before dawn on that day. However, the English Channel was rough, whipped up by a storm that some said was the worst in 20 years. All D-Day operations were postponed until further notice. The O’Brien returned to England and anchored in Portland.

The O’Brien left port the next day, its first mission to escort 45 LCI’s (Landing Craft, Infantry) to Utah Beach. But on the evening of June 5, Ray Woods picked up a sonar contact. Was it a German submarine? The destroyer dropped depth charges, and contact was soon lost.

At dawn on June 6, the O’Brien safely escorted its charges to Utah Beach without further trouble, but was then ordered to the waters just off Omaha Beach to provide standby support. Support was definitely needed. Omaha was a bloody shambles.

Omaha Beach was a four-mile stretch from Vierville-sur-Mer in the east to Colleville in the west. The infantry’s route inland was blocked by steep shingle slopes and treacherous cliffs, many some 150 feet high. This geography provided ideal high-ground defensive cover for the Germans. Those Omaha slopes were well fortified, boasting eight heavy guns, 35 antitank guns, and 85 machine guns. Elements of the 1st and 29th U.S. First Infantry Divisions on Omaha met with difficulties from the start.

Omaha was defended by the 352nd Division, the best German fighting unit on the Normandy coast. The landing craft were met with a withering fire from the first moment the ramps were lowered to disgorge the infantry. Scores fell dead and wounded, the survivors scrambling to find whatever cover they could. Some companies foundered about leaderless because every officer and sergeant was down.

At first, destroyers like the O’Brien were mute observers to the spectacle that was being played out before their horrified eyes. “We were off about 4,000 yards from the beach,” Woods grimly recalled recently. “There we watched the annihilation of the first wave. Bodies were floating in the water throughout the beach area.”

The second landing wave came in and likewise found itself in a meat grinder. The result was sickening. Around 9 am Captain Outerbridge felt he could stand no more. He wasn’t going to let his ship be an impotent spectator of the terrible drama that was being played out before his eyes. Without orders, Outerbridge headed closer ashore until the O’Brien was only 500 yards from the bloodstained beaches.

The skipper ordered a hard right until O’Brien paralleled the shoreline and its deadly cliffs. All 5-inch/38-caliber batteries commenced firing at the German pillboxes and machine-gun nests that were perched high above the beaches. After the first salvo, the ship received radio calls from Army units that were huddled at the bottom of the cliffs, unable to advance but unwilling to retreat.

Outerbridge asked if anyone had been hit by the ship’s salvo. No, came the reply—but please raise your fire, because we are here just below! O’Brien continued down the coast about a mile or so until reaching Pointe du Hoc. At one point, observers from the destroyer spotted German soldiers fleeing from the cliffs to a lone building just to the rear. It was quickly demolished—the soldiers still inside—by O’Brien’s well-aimed 5-inch shells.

Curiously, Outerbridge’s heroic action in bringing his ship so close to shore disappeared from the official record. The ship’s war diary, recently released by the U.S. government, states in part that the O’Brien arrived at Omaha Beach on June 6 at 2233 military time—10:33 pm. The ship’s log, signed by all officers, claims the destroyer stayed at Utah Beach until midnight.

Ray Woods confirmed that O’Brien did get close to Omaha Beach as described and did lend vital and much welcomed fire support to the soldiers ashore. He feels that, by accident or by design, there was a cover-up of Outerbridge’s heroic actions that morning.

Artillery Duel at Cherbourg

After the action off Omaha Beach, things were relatively quiet for the remainder of the day and into the night. After midnight, Woods was operating the ship’s SC aircraft radar, and he picked up some contacts about 100 miles out. It seemed to be “the whole German air force,” Woods said with a chuckle.

The Luftwaffe was a pitiful shadow of what it had been in the glory days of 1940 and during the Battle of Britain. The Allies ruled the skies over Normandy, so a major German air attack seemed unlikely. Woods remembered that the Germans might be jamming, dropping foil to create ghost “blips” on the radar screen. Sure enough, only one Junkers bomber, not a whole squadron, was flying overhead.

The O’Brien commenced firing, and Woods felt the ship suddenly sway. The bomber had released a stick of 250-pound bombs, narrowly missing the destroyer. It was the ship’s first brush with destruction, but it would not be its last. Within a few days O’Brien’s luck seemingly ran out.

D-Day was a success, and although there was still hard fighting in the weeks to come, the Allies were firmly on the Continent and there to stay. Nevertheless, it was deemed important that the Allies seize the nearest deep-water port available.

Cherbourg, located atop Normandy’s Cotentin Peninsula, was the logical choice. The Allies had already taken the approaches to the peninsula and by mid-June were at its base. The U.S. VII Corps, under General J. Lawton Collins, was given the task of taking the port city.

Hitler’s confidence was placed in General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben and the 21,000 German troops now bottled up in the peninsula. They were a mixed bag––everything from the exhausted remnants of the 709th Division to labor battalions and a few Kriegsmarine naval personnel. Yet Cherbourg’s fortifications were formidable and might prove a hard nut to crack.

It made sense for the Navy to bombard the port and soften up its defenses. Admiral Morton L. Deyo’s Task Force 129 received orders to bombard Cherbourg on its seaward side, so the admiral divided his force into two components. O’Brien was assigned to Task Group 129.2 under Rear Admiral Carleton F. Bryant which included the battleships USS Texas and USS Arkansas. Besides O’Brien, the destroyers USS Barton, USS Laffey, USS Hobson, and USS Hunkett were on hand.

The original plan was for the battleships to shell German shore batteries for 90 minutes, as directed by General Collins on land. Land-sea coordination was vital, and gunnery had to be precise because the U.S. 7th Infantry Division was operating on the outskirts of Cherbourg.

The O’Brien’s initial task was to support the minesweepers, which were clearing a path for the big battleships just behind. Once the German batteries were in range, the battleships poured salvo after salvo into them. The battleship Texas unleashed its 14-inch guns, the shells roaring over the O’Brien before crashing into their targets in gouts of smoke and flame.

But the German shore batteries were well protected, and even more importantly, well manned. Battery Hamburg, for example, was a concrete bulwark that featured four 240mm guns. The Germans held their fire until the American ships were within range, then opened fire in a furious counterbattery salvo. German shells bracketed the Texas, and within a few moments the battleship was hit.

The O’Brien came to the rescue, making smoke so that the Texas would not be such a perfect target. After screening Texas and Arkansas, the doughty little destroyer renewed its attack. All of O’Brien’s 5-inch batteries opened up at 13,200 yards, peppering the shore with a hurricane of shells. Stung by this barrage, the Germans turned from shelling the Texas to shelling the destroyer.

Captain Outerbridge immediately grasped what was happening and ordered a hard right rudder, at the same time increasing speed to 25 knots. The sea began to boil with foaming geysers of water marking each German near miss. O’Brien twisted and turned, snaking though a gauntlet of fire, and for a time the ship successfully escaped damage.

A German 240mm shell struck the aft starboard corner of the bridge, then ricocheted into the forward starboard 40mm gun mount. The shell detonated in a ball of yellow flame and dirty black smoke, ripping the ship’s body as if it were made out of paper. The 40mm gun mount was shattered, and the guns themselves knocked out. Everything within a radius of 15 feet of the blast was reduced to blackened pieces of twisted metal.

The ship’s CIC (Control Information Center)—where the radar was located—was a shambles, and fires raged all around. The flames were fed by 40mm shells and cartridges that had been set off by the initial blast. Luckily, the crew managed to extinguish the flames.

The O’Brien was badly hit, with 13 killed and 19 wounded. In the radar room, one man was killed and five wounded, but Woods was lucky enough to escape unscathed. “When the blast occurred,” he said, “the debris flew past me and Lt. Cmdr. Robinson, who was looking over my shoulder. There was nothing we could do but get out via a nearby hatch.” As they emerged from the wreckage and carnage, Robinson remarked, “Well, Ray, we’re on our second one.” It was an oblique reference to the old tale that a cat has nine lives.

Bloodied but unbowed, O’Brien stayed in the fight, firing her remaining guns until at last the task group broke off the action. Two days later, Cherbourg was in Allied hands and O’Brien limped back to England, where a burial service was conducted. Robert Montgomery was asked to say a few words at the service, which he did.

Sinking the Ward

The O’Brien then sailed home for the Boston Navy Yard and much needed major repairs. After about a month, when the ship was ready for sea again, orders came to travel to the Pacific via the Panama Canal. Eventually O’Brien joined the Seventh Fleet in operations off Leyte in the Philippines. Particularly memorable was the fighting in the Ormoc Bay region. While American and Japanese land forces grappled for possession of Leyte, air and sea battles raged off the coast.

The Ormoc Bay phase of the Leyte Gulf battle lasted for much of November and December 1944. Japanese warships tried to bring in reinforcements to their beleaguered forces on the island, and the U.S. Navy tried to interdict them. During this time, the kamikaze––Japanese suicide pilots and planes––made their appearance.

At the time, O’Brien, with Outerbridge still at the helm, was attached to Task Group 78.3, commanded by Rear Admiral Arthur D. Struble. The main duty of the task group was to escort the U.S. Army’s 77th Infantry Division’s amphibious landing at Ormoc Bay, Leyte. The men of O’Brien got their first real taste of what it was like to be a kamikaze target, something that would be indelibly etched into the memory of the surviving crew.

On December 7, 1944, O’Brien and USS Laffey were just behind some minesweepers and just ahead of the main U.S. forces that were about to land. By 6 am, O’Brien’s batteries were firing on enemy barges, barracks, and guns along the shore. At about 7 am, the landing craft went in and disgorged masses of well-armed U.S. infantry onto the Leyte shore.

Although a beachhead was quickly established, O’Brien’s task was still not completed. Captain Outerbridge ordered the helmsman to turn the ship along Ormoc Bay’s northwest shore to search for more targets. The destroyer got lucky and managed to locate additional shore batteries, some of which had been camouflaged, and additional barracks and barges.

But while O’Brien was engaged in this task, elsewhere a swarm of bogeys had appeared on some ship radar screens at about 8 am. These proved to be a swarm of Japanese twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” aircraft being used as deadly kamikazes. American antiaircraft guns peppered the sky, bringing down some of the planes, but some managed to slip through the screen. One of the ships, a former destroyer turned troop carrier, was badly crippled when a kamikaze smashed into it, igniting a number of fuel tanks. Soon the unlucky ship was engulfed in flames, the thick coils of black smoke ascending to the sky like a funeral pyre.

There next occurred a series of events so strange that, if written as a Hollywood script, would be rejected as too improbable and unrealistic. Captain Outerbridge received a signal aboard O’Brien that ordered him to assist the stricken vessel. Scanning the lines of the massage, he could pick out the name of the ship—USS Ward.

It was the same ship he had commanded on December 7, 1941, outside Pearl Harbor. And as if to underscore the incredible coincidence, he was being dispatched to aid the Ward on December 7, 1944—three years to the day after he ordered the ship to fire on the Japanese midget submarine.

Outerbridge would have done his duty in any event, but the fact that he was going to the rescue of the Ward must have given the mission an added poignancy. Outerbridge ordered full speed ahead, and O’Brien pulled out all the stops, managing to reach speeds of 27 knots in an effort to reach the Ward quickly. The sense of urgency was real because the flames were spreading fast, turning the aging vessel into a raging inferno.

The O’Brien approached from the port side, but the stricken ship was so engulfed in flames it was necessary to stand off 30 feet to enable fire hoses to do their work. Outerbridge did not order a firefighting party to go aboard because the Ward’s magazines were threatened. The task was made even more difficult by the fact that O’Brien was still under attack by rampaging kamikazes.

After a time, it became obvious the venerable old ship could not be saved, and Outerbridge was ordered to sink the Ward by naval gunfire. Outerbridge himself gave the command, and one can well imagine the thoughts that raced through his head at that moment. He had won a Navy Cross for his actions aboard the Ward. Now, by a strange twist of fate, he was ordering the ship’s destruction on the exact anniversary of that fight.

Struck by a Kamikaze

The next objective was supporting the invasion of Mindoro, an island in the central Philippines. After Leyte had been secured, Mindoro was considered a stepping stone to the all-important retaking of Luzon. The island of Luzon had both emotional and strategic importance. The big island was where Manila, the Philippine capital, was located, and it was the scene of the heroic defense of Bataan and Corregidor in 1942.

But it was during this period that O’Brien suffered a small tarnish on what was otherwise a sterling record. It happened in mid-December 1944, when the destroyer escorted some LSTs through the Surigao Strait. Two O’Brien crewmen stole some food, ammunition, and a rubber raft and secretly left the ship under the cover of darkness. They were able to get away in part because the LST’s were slow, and O’Brien was not going its usual speed.

The deserters were not discovered missing until the next morning, when predictably all hell broke loose. It wasn’t simply a matter of two AWOL sailors; these things occasionally happened in all branches of the military. But the missing pair had known that the ship was headed for Mindoro—if captured and interrogated by the Japanese, the entire invasion of the island might be compromised.

Outerbridge was summoned to a conference with Admiral Thomas Kinkaid and was informed that all was well––the two deserters were in U.S. custody. They had tried to join a Filipino guerrilla group ashore, claiming that they were the “survivors” of the destroyer O’Brien. Luckily for the war effort, the tale was not believed and they were turned over to American authorities.

After a fairly quiet Christmas and New Year’s, the O’Brien made ready to support the invasion of Luzon. American forces were going to land at Lingayen Gulf, the exact spot where Japanese forces landed in 1941 at the beginning of the war, and O’Brien one of over 800 ships participating. The destroyer provided fire cover, much as it had at Normandy roughly six months earlier. Although kamikaze action was heavy and several American ships were hit, O’Brien was lucky.

Later, Outerbridge’s ship and crew found themselves patrolling alone in the Sulu Sea without air cover. The kamikazes were still a major threat, and the ship radioed for fighters that could protect it. Army North American P-51 Mustangs arrived on the scene much to the relief of the O’Brien crew, but after a time the air cover had to depart and the destroyer was once again vulnerable.

The O’Brien’s luck finally ran out. A lone kamikaze appeared on the horizon and was able to get through the ship’s protective screen of flak. The plane collided with O’Brien’s portside stern. There were no casualties, but the ship was taking water from the hit. Damage control parties went to work at once, improvising a “patch” made up of odd pieces of wood and mattresses. After some shoring up, the ship doggedly, even courageously, continued her various assigned missions, including supporting underwater demolition teams and dueling with enemy shore batteries.

“I Was Among the Lucky Ones”

On January 18, 1945, O’Brien arrived at Manus, New Guinea, for three weeks of rest and relaxation while the ship was repaired. Woods said that New Guinea was close to the equator and no one’s idea of a vacation spot, but the crew was pleasantly surprised to find some compensation. There were beer and movies, and songwriter Irving Berlin was in person to present his USO show This Is the Army.

The respite, though welcome, was all too brief for the men of the O’Brien. The destroyer participated in a quick carrier raid, and, while on picket duty, got within 90 miles of the Japanese home islands. In February 1945, she was assigned fire-support duty in connection with operations at Iwo Jima.

March 21, 1945, saw O’Brien join Task Force 54 for the invasion of Kerema Retto. These islands may have not been major objectives in and of themselves, but once secured they would provide safe harbor for hospital ships or vessels damaged in the battle for Okinawa.

The O’Brien had gone through a lot in its relatively short service career, but it was now about to face its toughest ordeal. On March 27, a little after 6 am, four kamikazes were spotted skimming the low cloud cover, heading directly for the ship. O’Brien’s antiaircraft guns opened fire at once, peppering the air with explosives and shrapnel, sending two Japanese planes crashing into the sea in flames. A third was downed by American combat air patrol planes.

Unfortunately, the fourth kamikaze struck O’Brien just behind the bridge. The plane collided with the ship with a terrible ear-splitting roar, wounding Outerbridge and transforming the central superstructure into an inferno of leaping flames and blackened, twisted metal.

The suicide plane had hit the radio room, just behind the radar room. At one moment, Ray Woods was at his station, performing his duties. Then, without warning, all hell broke loose. “The blast threw me to the deck,” he said, “and everything was a cloud of black dust. I tried to see through it for some light, but all I saw was some cables hanging down from above.”

Woods tried to reach for the cables, hoping to use them to lift himself off the floor, but quickly let go when he found they were red hot. Somehow he got out of the smashed radar room and made his way up to the main deck. Still dazed, Woods went forward and then sat down for a moment; someone put a blanket over his shoulders.

Fires raged all over, but surviving crew members heroically manned the hoses and managed to get the flames under control. Captain Outerbridge reduced speed to 10 knots and nosed the ship into the wind, a maneuver that would help fight the fire. The destroyers USS Shannon and USS Gwin offered assistance and stood by to help protect the crippled O’Brien in case additional kamikazes showed up.

Some of O’Brien’s crew had either been blown off the ship when the plane hit or had dived off when they had been trapped by the flames. Once in the water, seeing their ship enveloped in oily black smoke, they were sure the destroyer was going to sink. It didn’t, and later the crew members in the water were picked up.

In the immediate aftermath of the kamikaze strike, Ray Woods remembered a particularly grisly sight: two crew members had been literally blown up to the crossarm of the mainmast. Their bodies still hung there, awful reminders of that terrible moment. “I don’t know who it was that climbed up and got them down,” Woods commented, “but whoever it was deserved a medal.”

The destroyer managed to limp back to Kerema Retto and came alongside a hospital ship. When O’Brien’s wounded were transferred to the hospital ship, Ray Woods was among them. He was surprised at being included because “although feeling very shaken by it all, I couldn’t see any physical injuries.” But once Woods looked at himself in a mirror, he was shocked at what he saw: “Most of my hair was burned off, all of my head and arms were black, and I had a burn on the left side of my face. However, I was among the lucky ones—lucky to be alive at all.”

The O’Brien’s final casualty count was 52 dead and 76 wounded. Twenty-eight of the deceased were buried at sea. The crippled destroyer was eventually ordered to Mare Island in San Francisco Bay for extensive repairs. Woods and many other crewmen had happy reunions with family and friends but in July 1945, the patched-up O’Brien was declared fit for sea duty again.

Witnessing the Japanese Surrender in Tokyo Bay

At one point in the summer of 1945, the O’Brien was anchored near the heavy cruiser Indianapolis in San Francisco Bay. The meeting was routine at the time, but later gained significance when the Indianapolis left San Francisco on a historic mission that would profoundly alter the course of the war. The cruiser was carrying the atomic bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, to the island of Tinian in the Marianas.

On the return voyage, the Indianapolis was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, resulting in one of the greatest maritime tragedies of the 20th century. The cruiser went down in 12 minutes, leaving about 900 men in the water. The victims endured thirst, exposure, and incessant shark attacks. Only 316 survivors were picked up and lived to tell the horrific tale.

In mid-summer 1945, the U.S. armed forces were gearing up for the invasion of Japan, and the O’Brien underwent “operational training” from July 21 to August 12. It was during this period that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were hit by atomic bombs.

The United States played a magnificent game of bluff, implying that it had many more bombs in its nuclear arsenal. In reality, there were none, and it would have taken many months to create more. Unaware of this fact and faced with the possibility of utter annihilation, Japan surrendered unconditionally on August 15, 1945.

In early September 1945, the USS O’Brien steamed into Tokyo Bay and anchored there. The official Japanese surrender ceremony had taken place on September 2, only a few days before the destroyer’s arrival. Since Germany had capitulated a few months earlier, the global conflict known as World War II had officially ceased. It was an ending that the officers and crew of the O’Brien had done more than their fair share to bring about. Rarely had a newly commissioned ship seen so much action in so short a period of time.

The O’Brien’s World War II career may have been over, but still she was not done. She was refurbished and saw action in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. The brave little “tin can” suffered an ignominious end, however, being sunk as a target ship in July 1972.

During four decades of faithful service, the O’Brien was awarded six battle stars for her World War II service, five battle stars for Korea, and three for Vietnam, making her one of the most honored American warships of all time.

My uncle was Radioman that day and was KIA by the Kamikaze attack.

My Father served on the O’BRIEN,think he was at the helm,or on the bridge. Have a scrapbook and photos of his

My Dad, Robert E Leddon served aboard the Obrien in WW2, does anyone remember him. I believe he was wounded at Kerema Retto. He died in 1969, would like to know what he did, what his battle station was etc.

Thank you

Robert Leddon Jr.

Darryl Byrge a sonarman and relative was killed by the kamikaze. He is listed as missing in action / buried at sea. Grateful for his service. Having been a D-Day and Iwo Jima he lived to age 20.

My father Lewis Cosby was a radar man on the USS O’ BRIEN. He was stationed on the ship during the D-Day invasion till the end of the war. He was there when they pulled into Tokyo Bay. He joined the navy at the age of 17. Just a young man from Mississippi who loved his country.

My uncle, Charlie Hosking, was a plank member on the O’Brian. He was a boilerman and was on her at D-Day til the end of WWII. He retired as a 20 year Sailor.