By Mark Albertson

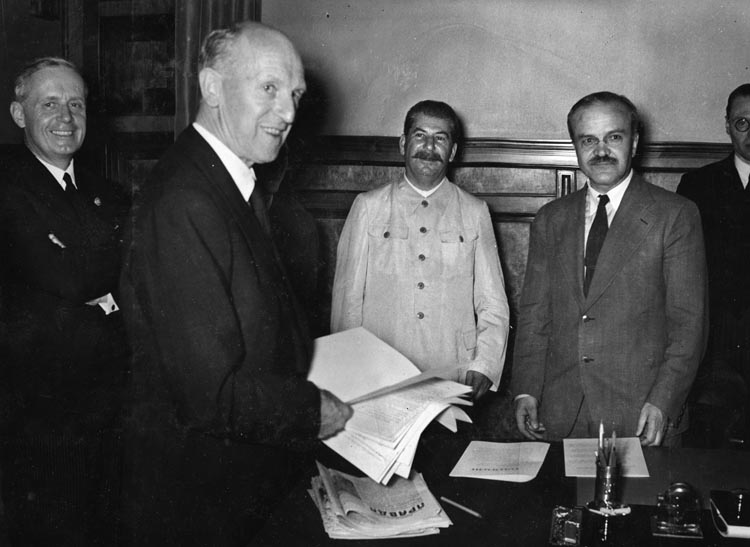

On August 23, 1939, Soviet Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, V.P. Potemkin, waited at the Moscow Airport for Joachim von Ribbentrop, Foreign Minister of Nazi Germany. He warmly greeted the former champagne salesman and then whisked him away for a clandestine meeting at the Kremlin.

Waiting to receive the emissary were Soviet strongman Josef Stalin and his granite-faced foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov. They concluded what became known as the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. Included were provisions governing the transfer of raw materials from the Soviet Union in exchange for manufactured goods from Germany. But, more importantly, the pact was a protocol establishing each signatory’s sphere of influence. This included Poland. Hitler and Stalin did not merely intend to partition their neighbor, they meant to wipe the country off the map. The Germans would begin to close the vise on September 1, advancing to Brest-Litovsk. The Soviets would close the eastern jaws on September 17 until Poland was gobbled up. As an added inducement for Stalin’s compliance, Hitler agreed that Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Bessarabia, which was on the eastern edge of Romania, would be included in the Soviet sphere of influence.

The pact was signed at 2 am on the 24th. The two dictators not only sealed Poland’s fate but set in motion a chain of events that would soon engulf the globe in World War II.

Bottles of champagne were opened to toast the historic moment. Stalin raised his glass to Hitler’s health. “A fine fellow,” remarked the Soviet dictator. Yet, 21 months later the pact would prove to be just another scrap of paper, for Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union would collide in a titanic struggle that was to become the greatest land war in history.

The Rise of Fascism, the Decline of the Allied Powers

By 1939, Italy, once in the Allied camp, was now a Fascist power under the sway of a swaggering brute named Benito Mussolini. Another former Allied power, Japan, was now militaristic, a self-serving belligerent selling itself to the masses of Asia as their deliverer from the bondage of the white man, while masking the brutal reality of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The United States seemed hopelessly absorbed in its delusion of self-quarantine and was determined not to mire itself in European politics.

This left Britain and France. Heart and soul of the Allied effort during the Great War, they were able to maintain the façade as power brokers at Versailles but emerged from the four-year contest of attrition as had many of their soldiers—as permanent invalids. And while they were hardly terminal, their economies were still unwell, playing host to cankers of damage and debt; in addition to being socially scarred from the unremitting bloodletting of the trenches, they hobbled along for the next 10 years until the Great Depression.

France, in particular, never seemed to emerge from either. Indeed, it seemed to seek solace in a bunker mentality induced by the Maginot Line, that impenetrable shield of France, a marvel of 20th-century construction with its underground railways, air conditioning system, and fixed fortifications which proved little better than monuments during the coming era of mobile warfare.

Hitler seemed to sense the weakness, testing the waters on March 7, 1936, with his occupation of the demilitarized Rhineland in direct contravention of the spirit of the Versailles and Locarno Treaties.

Common belief holds that the French reaction or lack thereof to the German provocation was owing to a lack of intestinal fortitude, girded by nightmares of Verdun. A policy memorandum of Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden dated March 8, 1936, shows the British government counseling diplomatic action, urging the French not to scale up to a military riposte to which French Foreign Minister Pierre Flandin stated that France would not act alone. Rather, Paris would take the matter to the League of Nations.

There is, however, another side to this story: the lingering effect of the Great Depression. The French were concerned with their economy and currency. They desperately needed investors like Britain and, in particular, the United States to help bolster the franc. Foreign investment in the franc was hardly possible if Paris was mobilizing for war.

Hitler had won his game of brinkmanship. With just a couple of untried battalions, he had faced down 100 French divisions, throwing cold water on the doubts of his nervous generals and sending his stature soaring among masses of the German people while exposing the fragility of Anglo-French cohesion and the debility of the Versailles and Locarno Treaties.

Chipping Away at the European Security Order

Such trysts of gamesmanship played by an opportunistic Hitler brought Europe to the brink. His understanding of history spurred him to isolate that colossal power to the East, Soviet Russia. The Hitler-Stalin honeymoon fractured the European balance of power, removed the Red Army as a counterweight to German ambitions, compromised Moscow’s membership in the League of Nations, and revisited British and French ostracizing of the Soviet colossus from European politics at Versailles.

Adolf Hitler assumed the chancellorship of Germany on January 30, 1933. He relied on diplomacy to advance the interests of Germany because he lacked the military muscle for a more belligerent posture. For instance, he ended the clandestine Soviet-German military cooperation of the 1920s. Yet on May 5, Germany and the Soviet Union renewed the 1926 Treaty of Berlin. On January 26, 1934, Hitler signed a nonaggression pact with Poland. On September 18, 1934, the Soviets joined the League of Nations, Germany having withdrawn from the diplomatic fraternity the previous October.

By forging a nonaggression pact with Poland, Hitler prevented Warsaw and Paris from reaching an agreement that would have sandwiched a prostrate Germany and blocked any potential deal between Warsaw and Moscow. This, of course, raised serious doubts in the Kremlin as to German-Polish intentions. The idea of collective security proved attractive, hence Moscow’s long overdue membership in the League.

Yet, by the Spanish Civil War it was abundantly clear that Rome and Berlin intended to spread the Fascist creed like a plague across Europe. German and Italian involvement in Spain’s conflict, in the face of British and French neutrality, seemed another step toward the eventual isolation of the Soviet Union. Moscow, then, threw its support to the Republicans against Francisco Franco’s Nationalists. For Germany, Italy, and Soviet Russia, the contentious Iberian Peninsula offered that battlefield laboratory for new weapons and tactics in preparation for the main event that was sure to come.

Five years after assuming power, Hitler felt more confident, having successfully affected the Anschluss with his homeland Austria on March 13, 1938, followed seven months later by adding the Sudetenland to the Reich from a friendless Czechoslovakia. Too late did the British and French understand the meaning of “no more territorial claims” when Hitler snatched Bohemia and Moravia on March 14-15, 1939, helping to complete the destruction of Czechoslovakia.

Thus the stage was set for the run-up to world war.

The “White” Directive

By March 16, 1939, Hitler had positioned Poland squarely between the German jaws of East Prussia to the north and the satellite state of Slovakia to the south. He now controlled the vaunted Skoda Works and added Czech tanks and guns to the Wehrmacht. Romania and Yugoslavia, arms customers of the Czechs, now had another supplier following Berlin’s hostile takeover. However, Hitler was not resting on his laurels.

On March 19, a “request” was forwarded to Vilnius. Lithuania was to hand over Memelland, which it had occupied since 1923, to the Reich and do so without delay. Four days later, Lithuania complied.

On March 21, Ribbentrop hosted the Polish ambassador, Josef Lipski, in Berlin. Hitler’s huckster urged the Polish diplomat to accept the deal offered the previous October. Danzig was to be returned to the Reich, a deal that included road and rail connections across the Polish Corridor. In return, Hitler would recognize the Corridor and Poland’s western borders. To sweeten the deal, territory was promised at Ukraine’s expense, a carrot to be finalized at some later date.

Lipski took the German offer back to Warsaw. He returned to Berlin on the 25th armed with Colonel Joseph Beck’s reply. The Polish Foreign Minister understood the machinations of the Führer. Caving in now would only invite another set of demands. Beck rebuffed Hitler’s offer, intimating that continued German pressure over Danzig would invite conflict. It was clear by the 31st that Polish resolve had been stiffened by London and Paris. On that day, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain addressed the House of Commons, assuring Warsaw that, in the event of a German attack, Britain and France would stand by the Poles. That evening, Hitler ordered Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (German high command), to prepare for Poland. On April 3, Keitel issued a directive known as “White,” ordering the German armed forces to be ready for action no later than September 1.

Not wanting to miss the bus, Italy invaded Albania. Hitler was less than pleased. He now faced the possibility of Britain playing on Turkish fears over the Dardanelles. German diplomat Franz von Papen was dispatched to Ankara for damage control.

Now the swing power was the Soviet Union, and the tide for influence was running against the Allies. Warsaw refused to allow the Soviet Army to transit Polish territory. Moscow proposed a six-power conference, which failed to gain traction. Any chance of prying Mussolini loose from the Axis seemed to have vanished. On March 26, Il Duce gave voice to Italy’s claims to the Mediterranean. With his April 7 invasion of Albania, he made clear his designs on the Balkans in tandem with Hitler’s plans for Eastern and Central Europe.

Testing the Waters With the Russians

Hitler, by this time, was taking a greater measure of the Kremlin. For instance, he noted that on March 10, during the 18th Party Congress, Stalin took aim at the Western democracies, stating that the Soviet Union was not going to war “to pull somebody else’s chestnuts out of the fire.” On April 17 in Berlin, Soviet Ambassador Alexei Merekalov called on Ernst Baron von Weizsacker, state secretary in the German Foreign Office. The topic of discussion was the possibility of improved German-Soviet relations and economic considerations.

On May 3, Stalin replaced Maxim Litvinov as Soviet foreign minister with Vyacheslav Molotov, a no-nonsense hardliner. Popular interpretation has it that Litvinov, a Jew, was replaced as a sop to the anti-Semitic Nazis. However, German diplomat Werner von Tippelskirsch observed in a May 4 telegram to Berlin, “Since Litvinov received the English ambassador as late as May 2 and had been named in the press of yesterday as a guest of honor at the parade, his dismissal appears to be the result of a spontaneous decision by Stalin. The decision apparently connected with the fact that differences of opinion arose in the Kremlin on Litvinov’s negotiations. The reason for differences of opinion presumably lies in a deep distrust, that Stalin urged caution lest the Soviet Union be drawn into conflicts. Molotov (no Jew) is held to be ‘most intimate friend and closest collaborator’ of Stalin. His appointment is apparently to guarantee that the foreign policy will be continued strictly in accordance with Stalin’s ideas.”

Stalin might have played the anti-Semitic card in ridding himself of Litvinov, but in the end the Soviet dictator was a political realist. The Soviets lost territory to the fledgling Polish state in their 1919-1921 armed contest. If there was a way of recouping territory and pushing the Soviet border farther west, then Stalin was certainly interested. As Austria and Czechoslovakia had shown, Britain and France proved lacking as allies in the face of Fascist provocations.

Hitler ordered his ambassador to Moscow, Count Werner von der Schulenberg, to put out feelers to Molotov. On May 5, Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels forbade disparaging pronouncements toward Bolshevism and the Soviet state until further notice.

The Allied Decision to Support the Poles

For Paris, Poland proved a dilemma. Warsaw would not allow Soviet troops across its territory during the Czech Crisis. And with Chamberlain’s pronouncement on March 31, it meant only one thing. England had no army on the European continent. France did. It seemed the Anglo-French-Polish accord, then, was to be guaranteed by the blood of the Poles and the French. France faced a problem. Germany blocked the way to Poland, just as Poland blocked the way to Czechoslovakia for the Soviets. It was imperative, then, that a deal be struck with Moscow.

Churchill concurred and had said so in the House of Commons back on April 3, commenting, “To stop here with a guarantee to Poland would be to halt in No-Man’s Land under fire of both trench lines and without shelter of either…. Having begun to create a Grand Alliance against aggression, we cannot afford to fail. We shall be in mortal danger if we fail…. The worst folly, which no one proposes we should commit, would be to chill and drive away any natural cooperation which Soviet Russia in her own deep interests feels it necessary to afford.”

Former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George echoed his protégé’s sentiments: “If we are going in without the help of Russia, we are walking into a trap. It is the only country whose arms can get there…. If Russia has not been brought into this matter because of certain feelings the Poles have that they do not want the Russians there, it is for us to declare the conditions, and unless the Poles are prepared to accept the conditions with which we can successfully help them, the responsibility must be theirs.”

For Chamberlain, a Conservative Party prime minister, such criticisms from the Labor bench provided another hurdle to the Polish Crisis, opposition at home. He had been sanctioned for not helping the Czechs at Munich and was now being taken to task for being led by the nose by the Poles. However, was not Britain defending the rights of smaller nations? This point was made by Lord Halifax to the House of Lords. Why should the Poles, then, be forced to accept assistance from a people with whom they have a long historic antipathy?

If Chamberlain’s negotiations with Moscow proved fleeting, then he and his government would incur blame. If, on the other hand, discussions proved fruitful, credit would have to be shared with Churchill, Lloyd George, and the Laborites.

Hitler Wins the Diplomatic Contest

The Chamberlain government seemed to drag its feet with Moscow. London’s first overtures were on April 15; Moscow replied in two days. The British did not answer until May 9, with Moscow coming back in five days. Again London was slow on the draw, 13 days; the Soviet reply, 24 hours. The British took another nine days with a Soviet riposte in 48 hours. The next go around saw London take five days versus 24 hours for Moscow, then another eight days for the British, 24 hours for Moscow. Six more days for the British, 24 hours for Moscow. The substance of the British communiqués is unimportant when compared to London’s spiritless approach to what must be construed as being a diplomatic dilemma of the utmost significance. Indeed, the leisurely pace of the British Foreign Office told Stalin everything he needed to know.

In comparison, the string of cables traded by the Reich Chancellery and the Kremlin show a great deal more attention to the seriousness of the agenda in question, particularly in the exchanges through July and August. These German Foreign Office missives tell a tale of woe for Poland. By this time, the position of the Polish state was untenable. Hitler had abrogated the 1934 German-Polish nonaggression pact, ended the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, and concluded nonaggression pacts with Estonia, Lithuania, and Denmark, in addition to the Pact of Steel with Italy, on May 22, 1939. It seemed that by summer, Hitler had sealed Poland’s fate.

In the autumn of 1939, for the time being, the previous discord between Fascist and Communist was conveniently forgotten. The delusion of rapture instilled by the Nazi-Soviet honeymoon seemed to presage a new era in German-Soviet relations, a marriage of convenience by which the newlyweds exchanged their meaningless vows before a sacrificial altar called Poland.

The tragedy of Poland goes beyond the Hitler-Stalin Pact and the insidious agenda of aggression it has come to represent. It assured that by 1945, in the throes of Allied victory, Poland would merely exchange one overseer for another.

Like Catherine the Great, Stalin was able to push the Russian border west at the expense of the Poles. In the 20th century, Germany and Poland had already invaded the Motherland twice by 1920. However, the nonaggression pact with the Nazis, in the end, failed to buy that breathing space necessary to prepare for the next Teutonic invasion, Operation Barbarossa, on June 22, 1941.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments