By David H. Lippman

The moon like a tray was sinking in the western sea and the deep red sun showed its face to the east. Samah harbor, shimmering with gold and silver waves, was as beautiful as a picture. The men on the convoy looked towards the bows … as the Navy formed in two lines to right and left of the convoy.… This was surely the starting point which would determine the destiny of the nation for the next century. The die was cast.”

So wrote Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, chief planner of Japan’s 25th Army, on the night of December 4, 1941. He was describing the sortie of convoys carrying Japanese forces from Hainan Island to invade Malaya and conquer Britain’s fortress at Singapore. It was described as impregnable. It would fall in 73 days.

Singapore and Malaya were the centerpieces of European domination of Southeast Asia. Since its founding in 1821, Singapore had grown to become one of the shining jewels in Britain’s imperial crown. Malaya produced 60 percent of the world’s rubber and 58 percent of the world’s tin. Singapore City was a major port and trading center, filled with Malays, Chinese, Indians, Indonesians, and Europeans, all trying to get rich amid Malaya’s incredible heat and humidity. By 1941, Malaya’s population was about 4.5 million, half of them Chinese, the rest Indian Tamils, ruled by 20,000 Britons through a complex web of treaties with local sultans, federated states, and crown colonies.

As Japanese imperialism spread across Asia in the 1920s and 1930s, Singapore was also seen as the central bulwark of defense of Britain’s vast Pacific interests, which included Australia and New Zealand. British strategy planned for deployment of a large fleet to Singapore in case of crisis. That required a major naval base, which was constructed in the 1930s. The base in turn required defense against enemy attack, which led to a mighty debate between the Royal Navy, the Army, and the Royal Air Force over the merits of torpedo planes and heavy guns.

In the end, the gunners won out and Singapore’s defenses included three massive 15-inch guns. Contrary to popular belief, these guns could fire inland as well as out to sea. However, they lacked high-explosive ammunition to use against an attacking ground force. Their ordnance was armor-piercing shell to penetrate warships’ hulls.

Other than the deployment of coastal artillery, Malaya’s defenders agreed on nothing. The Army ignored repeated staff studies and tabletop war games that showed an enemy force could storm through Malaya’s jungles from north to south, and prepared its defenses against seaborne invasion near Singapore. Without consulting the Army, the Royal Air Force set up a string of airfields in Northern Malaya to see if they were defensible against ground attack.

The only person who seemed to realize that the defenses of Singapore and Malaya were bound together was the deeply religious and highly capable General Sir William Dobbie, who commanded Malaya’s defenses in the late 1930s. He reported to London that despite the October-to-March monsoon period an enemy force could land at Northern Malay ports such as Kota Bahru, or southern Thai ports such as Singora and Patani, and drive down the vast network of roads into Singapore. The report was ignored, save for the construction of £60,000 worth of pillboxes on the southern shore of Singapore Island and Johore.

As Japanese troops plunged into China, killing hundreds of thousands of civilians, Malaya’s civilian and military leadership ignored the mounting peril, instead keeping busy meeting increasing orders from Britain and America for rubber and tin. In the third quarter of 1941, Malaya shipped 137,331 tons of rubber to the United States alone. In Singapore, white businessmen and officials wore evening dress for dinner, signed chits for whiskey and soda at the air-conditioned restaurant in Robinson’s Department Store, and played tennis and golf at their clubs.

London ordered Malaya to develop the civil defense tools—such as Women’s Voluntary Services and Air Raid Precautions—being used with great success in England, but nobody took them seriously, least of all the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Shenton Thomas. He would not let the Army use civilian labor to build entrenchments, saying that industry needed the workers, not the military.

It all seemed pretty academic anyway. Nobody took the Japanese seriously. Everyone believed them to be buck-toothed, imitative incompetents with poor night vision and no mechanical aptitude, unable to defeat the weaker Chinese. Intelligence reports from British officers in China on the ferocity of Japanese troops in battle were ignored. A report on the nimble and deadly Japanese Mitsubishi Zero fighter was lost.

On paper, Malaya’s defenses were quite formidable. The boss was Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, a World War I Royal Flying Corps veteran. From his headquarters in Singapore’s Fort Canning, he issued confident communiqués that had little connection to reality and fell asleep during staff meetings.

Below him stood the top Army commander, Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival. Buck-toothed, skinny, and colorless, Percival did not carry the image of a commanding general. The troops snickered at Percival, who insisted on going around in a pith helmet straight out of Kipling’s stories. Percival was a good administrator and a decorated combat veteran, but lacked toughness, brilliance, and drive.

Born in 1887, he had joined the British Army as a private in World War I at age 27 and rose to lieutenant colonel, surviving the trenches in France to command a battalion by 1918. He won a Distinguished Service Order and Bar, a Military Cross, and the French Croix de Guerre. After the war, he served in Ireland and graduated from the Staff College, showing a remarkable ability for paperwork, the bane of all armies. With the outbreak of World War II, Percival sought a field command and in March 1941 was appointed General Officer Commanding in Malaya.

Percival commanded a large force. The 3rd Indian Corps, under Lt. Gen. Sir Lewis Macclesfield “Piggy” Heath, was responsible for Northern Malaya. It consisted of two divisions, the 9th and 11th Indian (both divisions short of one brigade), as well as the 28th Indian Brigade. In Johore, Percival had the 8th Australian Division, consisting of two brigades, under Maj. Gen. Gordon Bennett, a decorated Gallipoli veteran and militia officer. In Singapore, Percival had the 1st and 2nd Malaya Brigades and his command reserve, the 12th Indian Brigade.

Percival’s force totaled around 86,000 men in 31 battalions, including some renowned units such as the Gurkhas, Sikhs, Punjabis, and the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

In reality, it was a hollow force. Most of the Indian battalions had been “milked” of experienced officers and NCOs, who had been sent to train new battalions or fill out battered ones in Libya and East Africa. Often the replacement British officers could not speak the languages of their men, such as Urdu or Hindustani.

The Australians had undergone very little training and seen no action. An Australian officer observed that his men had “enlisted on a Friday and reached Singapore that Monday.” None of Malaya’s defenders had trained to fight tanks. Many had never even seen one. There was not a single tank in the entire Malaya command. Bundles of leaflets on how to build and use antitank defenses sat on shelves in Singapore and did not make it to the frontline troops until the “balloon went up.”

Training itself was hard if not realistic. Officers ignored mangrove swamps and jungles in exercises and planning. The only outfit that trained for jungle warfare was the 2nd Argylls, whose commanding officer, Colonel Ian Stewart, was regarded as eccentric by his superiors because of his harsh regimen.

The Royal Air Force was not much better. Brooke-Popham said, “We can get along all right with Buffaloes out here.… Let England have the Hyper-Hurricanes and Super-Spitfires.” Actually, Brooke-Popham was covering up the unpleasant fact that Britain could not spare any modern fighters for Malaya because of her immense commitments in Europe and the Middle East. Malaya’s air defense required 582 first-line aircraft. There were only 158 planes ready to fly and 88 in reserve instead of the 157 authorized.

Worse, not one of the British, Australian, or New Zealand planes in Malaya was an up-to-date aircraft. The four fighter squadrons (243rd RAF, 21st and 453rd RAAF, and 488th RNZAF) flew a total of 60 American-built F2A Brewster Buffaloes, which were slower than the Japanese Zero and frequently suffered from loss of power due to a drop in oil pressure and overheating. The RAF’s four squadrons of 47 Blenheim bombers looked useful, as did the two squadrons of 24 RAAF Hudson patrol planes, but the 24 Vickers Vildebeeste torpedo bombers sputtered along at less than 90 miles an hour. With their open cockpits and yards of wires, they looked like a throwback to World War I. Most of the Allied pilots had just finished their solo training.

The top brass did not get along well either. Heath was senior to Percival, who had been promoted over Heath’s head for the Malaya job. Sir Shenton Thomas thought military preparations interfered with business. Chief Colonial Secretary Stanley Jones was an obstructionist mandarin who valued regulations over action. Into this mix was flung Sir Alfred Duff-Cooper, a tactless and aggressive cabinet minister who had been sent out from London in December 1941 with executive powers to serve as Resident Cabinet Member for the Far East. He berated Brooke-Popham as the “worst sort of old-school tie” and ridiculed Thomas.

The Royal Navy was not in any better shape. Three outdated light cruisers headed the Singapore squadron. As war came closer, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered a task force consisting of two battleships and an aircraft carrier sent to Singapore as a deterrent and morale booster. The ships chosen were the new Prince of Wales, Britain’s latest dreadnought, and the older Repulse, a battlecruiser that had been in service since Jutland, yet had never fired her guns in anger. The carrier, Indomitable, ran aground during work-ups in Jamaica and never made it to Malaya, which would prove fatal for the other two capital ships.

The two battlewagons steamed into Singapore on December 1, 1941, under the command of Admiral Sir Tom Phillips. The big ships drew cheers as they steamed into Singapore harbor, as visible displays of the Royal Navy’s traditions of power and invincibility.

The Japanese, however, were not impressed. They had an extremely clear intelligence picture of Malaya. Japanese agents covered the country, working as dentists, photographers, fishermen, and traders. Even the official photographer of the Singapore Naval Base was a Japanese spy. The Japanese opened consulates in Singora and Patani across the Thai border and filled them with “special attachés,” who were actually spies.

Major Terundo Kunitake, an engineer, had been assigned to the Japanese consulate in Singapore. He spent his time making detailed surveys of Malaya’s roads, bridges, and rivers, creating maps that were more accurate than those used by the British.

The Japanese noted that despite Malaya’s mountains and jungles it was well crisscrossed with concrete roads, including a major trunk highway from Singora down the West Coast to Singapore, perfect for a motorized advance. Japanese spies reported to Tokyo that the British propaganda about Singapore’s impregnability was a bluff.

Japanese spies cultivated fifth columnists and disaffected Indian troops. Japanese agents funded the Indian Independence League, spreading anti-British propaganda. One of the men they subverted was no Indian, though, but a New Zealander, Captain Patrick Heenan, the British Army’s liaison officer to the Royal Air Force. Equipped with a portable radio set in a fake chaplain’s communion set, he provided valuable information to the Japanese on the RAF’s superb Northern Malaya airfields and its lack of defenses right up to the first two days of the war.

Another vital intelligence source landed in Japanese hands on November 11, 1940, when the disguised German merchant raider Atlantis stopped the British freighter Automedon in the Indian Ocean. When the Briton refused to silence his radio, Atlantis hurled 5.9-inch shells into Automedon’s bridge and radio room, killing everyone there.

Lieutenant Ulrich Mohr and his boarding party raced over in Atlantis’s launch and tore open the old ship’s strong room. They found 15 bags of secret mail, including British merchant decoding tables, fleet orders, gunnery instructions, and naval intelligence reports. Next to the shattered radio console Mohr found a bag marked “Highly Confidential … To Be Destroyed.” Inside was a report addressed to “C-in-C Far East … To Be Opened Personally.”

Back on Atlantis, Mohr and his skipper, Captain Bernhard Rogge, broke open the papers. Mohr was a skilled linguist and easily translated the War Cabinet Planning Division’s latest appreciation of the British Empire’s strength in the Far East. He gaped at deployments of RAF units and naval strengths in Malaya, along with vast notes on the Singapore fortifications. The paper even pointed out that it was unlikely Singapore could be held in case of an extended siege. Rogge, who would retire an admiral despite a Jewish background, dispatched the documents to Yokohama aboard the prize Norwegian tanker Ole Jacob.

When the Japanese received the documents, they initially thought they were fakes. But when they compared them with what their spies reported in Malaya, they were amazed. After Singapore fell, Rogge would become one of three Germans (the other two being Hermann Göring and Erwin Rommel) who would receive a jeweled samurai sword from the Emperor of Japan as a gesture of thanks.

All of this intelligence was useful to the Japanese, as their army had little experience operating in jungles. To overcome this problem, the Japanese created the “Taiwan Army Research Unit” in Formosa in 1941, under Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, an arrogant but brilliant officer. This blandly named unit, consisting of 11 men, was to research and develop every aspect of campaigning in tropical climes. Tsuji and his men worked out tactics and logistics, often going out into Formosa’s jungles to test their theories. The result of their planning was a thick pamphlet issued to every soldier who invaded Malaya, which Tsuji grandiosely entitled, Read This Alone—And the War Can Be Won.

He was nearly right. The booklet provided the Japanese soldier with a dose of propaganda, useful rules to follow during the ocean voyage to Malaya, and procedures for battle, marching, hygiene, and signaling in Malaya’s terrain. It even reminded troops to carry a hand fan on the march to help keep cool. “Officers and men, the eyes of the whole world will be upon you in this campaign, and working together in community of spirit, you must demonstrate to the world the true worth of Japanese manhood,” the book concluded.

The manhood assigned to the conquest of Malaya was the 25th Army, based on Hainan Island. Their commander was appointed on November 2, 1941. Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita was a burly officer who had served as military attaché in Switzerland and commander of the Kwantung Army in China. Yamashita was very familiar with modern European weapons and techniques. In 1940, he led a military mission to Germany that studied the Nazi war machine in detail. Yamashita had gone all the way to Calais, watching British and German aircraft dogfight over the English Channel. Married to the daughter of a general, Yamashita was a deeply religious man who did not own or drive a car and enjoyed fishing and gardening.

Yamashita had also become mixed up in the bloodthirsty politics of the interwar Japanese Army and was connected to coup attempts and assassinations during the 1930s. Prime Minister Hideki Tojo disliked and distrusted Yamashita. The feeling was mutual.

When Yamashita took command of the 25th Army, six days short of his birthday, he knew very little of the Malayan situation, but absorbed Tsuji’s information rapidly and placed the colonel’s team on his command staff.

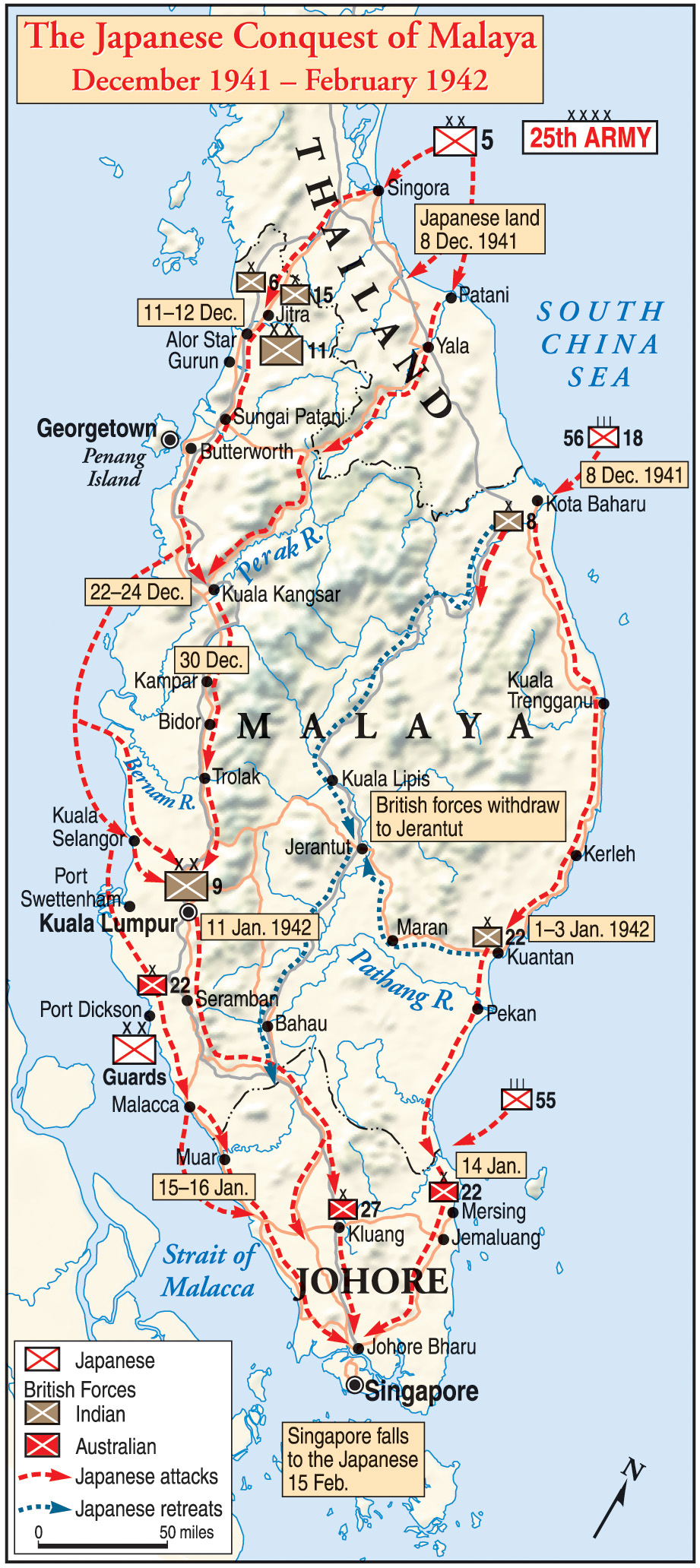

Tsuji believed that the best way to take Malaya would be to invade the peninsula from the north, storming ashore at Singora and Patani in Thailand, then driving south down the main highway on the west coast, and taking the fortress from the rear—exactly as British wargamers and Dobbie had believed. Yamashita agreed with his planners.

Offered five divisions to take Malaya, Yamashita said he would need only three. Tokyo planners were astounded by Yamashita’s sang-froid—three divisions against Asia’s greatest fortress—but Yamashita realized that his supply line would be long and thin, and he lacked both sea and land transport. A lean force would accomplish more than a heavy one.

Two of Yamashita’s divisions were outstanding outfits: Maj. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi led the 18th Infantry Division and had served as Yamashita’s chief of staff. Mutaguchi was exceptionally ambitious. The 18th Division deployed 22,206 men, but had only 33 vehicles. A total of 5,707 horses would haul the division’s supplies into battle. General Takuro Matsui led the 5th Infantry Division, which had launched amphibious assaults on China. The 5th was well-supplied with wheeled transport, totaling 1,008 vehicles, to move its 15,342 men. Both divisions were old-style “square” divisions of two brigades and four regiments.

The third outfit, however, General Takuma Nishimura’s Imperial Guards Division, had not fought a battle since 1905. Its men were selected for their height, not fighting ability, and they were used primarily for ceremonial occasions. When Yamashita saw them in maneuvers on Hainan Island, he was enraged at their ineptitude. He ordered Nishimura to lay on realistic combat training, but the snobbish Guardsman refused. When the Imperial Guards loaded their transports for invasion, they were considered one of the worst-trained divisions in the Imperial Japanese Army. A modern “triangular” division with three regiments, it had 12,649 men and 914 vehicles.

Yamashita also had supporting engineer and tank regiments for each of his three divisions, well equipped to replace blown bridges. Although short on transport and logistical units, a typical Japanese failing, 25th Army was one of the toughest armies on earth. Its secret weapon was the bicycle, which enabled Japanese troops to move swiftly and silently down Malayan roads. Including the headquarters guard and paperchasers, it all added up to 88,000 men.

Yamashita also enjoyed strong naval protection, with an ample supply of warships to escort his convoys heading south. His trump cards were the Army’s 3rd Air Division and the Navy’s 22nd Air Flotilla. The Army would bring 146 fighters, 172 bombers, and 36 reconnaissance planes into battle, while the Navy had 36 fighters, 138 bombers, and six reconnaissance machines. With 564 aircraft, Yamashita enjoyed a 5-to-1 numerical advantage over the Allies.

Yamashita also had a massive aerial technological advantage. The Navy’s Zero and its Army knock-off, the “Oscar,” could fly rings around the British Buffaloes. The Army’s Ki-97 “Sally” bomber carried a 2,200-pound bomb load, twice the punch of the British Blenheim. The Navy’s Mitsubishi “Betty” bombers could carry the same load or the Type 95 Long Lance torpedo, the finest in the world. Unlike their British counterparts, Japanese aviators had extensive experience, having fought in China.

Japan’s war plan depended on surprise, speed, and timing. On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in America), they would attack across the Pacific, hitting Hawaii, Guam, Wake, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Malaya. Japanese troops would march into Thailand and gain that nation’s alliance. The British planned, in the event of an impending invasion of Malaya, to launch Operation Matador, which called for a brigade group called Kroh Column to race from Malaya into Thailand in a preemptive strike and grab Singora and Patani before the Japanese arrived. Nobody on the British side thought this would ever happen.

Even when Yamashita’s transports were sighted in the Gulf of Siam on December 6, and the Straits Times reported “invasion imminent,” Brooke-Popham phoned the newspaper’s editor, Jimmy Glover, and accused him of alarmist reporting. “The situation isn’t half as serious as you make it out,” Brooke-Popham said.

“That’s not fair,” Glover retorted. “This information was passed by the censor. To me the presence of those transports off Cambodia Point means war.” Brooke-Popham had no answer, but he and his staff debated the big issue: whether or not to launch Matador. If Kroh Column and its troops raced into Thailand, the vacillating neutral Thai government might react to this invasion as reason to ally with the Japanese. On the other hand, if British troops got to Singora and Patani ahead of Yamashita’s convoys, they could be stopped on the beaches.

London had delegated this vital decision to Brooke-Popham, and he and his staff debated. Was this a Japanese invasion or a ruse to make the British invade Thailand and put that nation on Japan’s side? Heavy rain prevented further reconnaissance off the coast, but Brooke-Popham’s answer came in a panicky telegram from Sir Josiah Crosby, British Minister in Thailand. He said, “For God’s sake do not allow British forces to occupy one inch of Thai territory unless and until Japan has struck the first blow at Thailand.”

That settled it for Brooke-Popham. He ordered the 11th Indian Division to be ready for Matador, but not to launch it. Kroh Column and the Indian troops moved forward to the border in drenching rain, awaiting orders.

As the weather deteriorated with the monsoon’s onset, the Japanese convoys split up to reach their targets. First was the Kota Bahru force, under Maj. Gen. Takumi, whose main purpose was actually to grab the port and divert British attention from the main landings in Singora and Patani.

Just after midnight on December 8, the Japanese began unloading their transports. Takumi wrote, “There was the dull light of an oval moon from over the sea to the east. A stiff breeze was blowing and I could hear it whistling in the radio aerials. The waves were now up to six feet.”

In the heavy sea and winds, it was difficult to lower the landing craft into the water. They swung in their davits and crashed into the transports’ sides. Any more wind and chaos would result. In the landing craft, Takumi’s men were “not only encumbered with lifejackets, but with rifles, light machine guns, ammunition, and equipment. It was very hard to jump into the landing craft, and even harder to move forward to our places. At intervals a soldier would fall screaming into the sea, and the sappers would fish him out.”

It took an hour for the landing craft to reach the shore, but when they did, they came under heavy machine-gun fire from Brigadier Billy Key’s 8th Indian Brigade.

The landing set off alarms, which rocketed up the chain of command to Fort Canning in Singapore. At 1:15 am Percival phoned Sir Shenton Thomas to inform him of the Japanese attack. Thomas’s reaction was quite casual: “Well, I suppose you’ll shove the little men off!” That accomplished, Thomas awakened his wife and servants, ordered coffee on the large first-floor balcony of his house, and wrote out a proclamation for the “First Degree of Readiness.” Amazingly, it did not call for a blackout.

Meanwhile, at Kota Bahru, the war heated up. RAF Blenheim bombers attacked the invasion force, hitting Takumi’s headquarters ship, the Awajisan Maru. Instead of heading for another ship, Takumi headed straight for the shore, ignoring naval pleas to abort the assault. On the beach, his men were pinned down by Indian Bren guns. Takumi ordered his officers to lead the men inland, outflank the British positions, and overrun them. By 4 am, Takumi’s men were off the beach and heading inland.

That word reached Yamashita as his main force landed in Singora. Finding no resistance, Japanese troops came ashore in parade order. Yamashita himself hiked over to the Thai provincial governor’s residence to demand free passage through Thailand.

At the same time, Air Vice Marshal C.W.H. Pulford phoned Sir Shenton Thomas with more bad news: Enemy planes were approaching Singapore, which was not blacked out. Thomas, stunned, alerted the Harbor Board and Air Raid Precautions, but nobody could find the engineer with the keys to the big switches at the power plant. It would not have mattered anyway. Most of the streetlights in Singapore were gas lamps and had to be lit or extinguished by a man with a long pole, one at a time, a process that took hours. When the 22nd Air Flotilla’s “Betty” and “Sally” bombers roared over Singapore at 4:15 am, the whole city, including Fort Canning, was fully lit.

Japanese bombs pasted Singapore. Sixty-one people were killed and 133 injured. One bomb blasted open Robinson’s air-conditioned restaurant on Raffles Place. Japanese bombers rumbled over the city, unimpeded by RAF night fighters. Even though three RAAF Buffaloes were fueled and ready to fly, the RAF command would not let them scramble, afraid they would be shot down by jittery antiaircraft gunners.

By dawn, the air raid was over and Singapore was in the war. So was the entire Pacific Ocean, as the news tickers spit out reports of Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor … Wake … Guam … the Philippines … and Hong Kong, all describing a string of Allied disasters.

Muddle continued on the Malaya-Thailand frontier. While Japanese troops unloaded in Singora and Yamashita browbeat Thai officials into providing his men with unimpeded passage (accomplished by 1 pm), the 11th Indian Division soaked in the rain, awaiting orders. Brooke-Popham could not locate Percival all morning, so it was not until 1 pm that Maj. Gen. D.M. Murray-Lyon learned that Matador was off, and he was to withdraw his troops to equally waterlogged trenches at Jitra.

Things were little better at Kota Bahru. The Japanese took 15 percent casualties fighting British troops, who were struggling to defend the airfield against ground and air attack. At 4 pm, a rumor swept the Indian lines that the Japanese had broken through. The airfield’s ground crew blew up their installations and drove off before Key and his staff could countermand the panic. The RAF withdrawal denied Key’s men any form of air cover, so Key was forced to withdraw.

All day long the Japanese Air Force pounded RAF bases whose locations and strength had been provided by Patrick Heenan, the traitor. From his base at Alor Star, Heenan transmitted reports on RAF activity to the Japanese on his radio. When the Japanese had not hit Alor Star by 10 am, an RAF airman asked Heenan, “Why haven’t we been hit? We’re in the front line.”

“Oh, they will do,” Heenan answered cheerfully. “They will do.” At 11 am, shortly after the base’s Blenheim bombers landed to refuel and rearm, 27 Japanese bombers arrived, blasting open nine Blenheims with light fragmentation bombs and killing nine people. One bomb hit the dispensary, exploding the supply of pharmaceuticals.

The timing was perfect. The Japanese had known from Heenan not to attack Alor Star until its bombers were on the ground. Army Private “Bladder” Wells pointed out to his sergeant, “Every time we make a move, Captain Heenan seems to push off somewhere.” Heenan had a neat trick of vanishing just before any action at Alor Star that day. His odd behavior attracted the attention of his commanding officer, Major James Cable France, but France was too busy coping with disaster to investigate Heenan. The RAF team at Alor Star was ordered to pack up during the night to evacuate south to the base at Butterworth.

By the end of the day, the RAF was down from 110 aircraft to about 50. The Japanese had gained complete air superiority.

Disasters continued to accelerate for the British. That evening, the battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse steamed out to sea without air cover to intercept the Japanese convoys off Singora. On December 10, Japanese bombers caught the two dreadnoughts and sank them. Phillips went down with more than 830 fellow sailors, still radioing Singapore to send tugs instead of fighter aircraft. The British ships never got near the convoys.

The sinkings were catastrophic for British morale. Reporter Ian Morrison wrote, “Blown clean away at one fell swoop was one of the main pillars on which our sense of security rested.” At the Raffles Hotel, the radio announcement stopped the dancing and music, and everyone went straight home.

On the morning of the 9th, the RAF team at Alor Star left. As they set off, Major France was asked to put a chaplain’s communion set in his car. France did so, but he was surprised to see another one in the back of a truck. France knew his chaplain had only one such set in the unit. He took the second case into his office, opened it up, and found Heenan’s radio. Setting a trap, France put both sets in his car and set off for Butterworth. Once there, he and aides watched the parked car to see who would take the fake set.

Heenan opened the car, looked through the sets, and left with the one that contained the radio. France had his man. He notified his superiors, and Chief Inspector Sandy Minns of the Straits Settlement Police came up with a company of armed civilian and RAF police to take Heenan into custody.

The traitor tried to flee in civilian clothes before the cops and Red Caps showed up, but lacked the nerve, so he returned to face the music after notifying the Japanese on his radio of RAF movements at Butterworth. The Japanese pounded the base and knocked out all but one of the Blenheims. By evening Heenan was in a Penang jail cell, awaiting court-martial in Singapore. News of his treachery, wildly inflated, spread through the British forces, damaging battered morale even further.

British organization did not get much better. Churchill appointed Duff-Cooper as president of the War Council for Malaya, with cabinet rank. The civilian disliked the military commander-in-chief, Brooke-Popham. The dislike was mutual, as Brooke-Popham resented Duff-Cooper’s abrasive personality. The two argued incessantly.

While the British command was a model of discord, Yamashita’s men, some using requisitioned Thai trucks, were moving lickety-split toward Jitra and the airfield at Alor Star. The key to Japanese mobility was their secret weapon, the bicycle, which could be used on Malaya’s many roads and on narrow wooden bridges hastily flung up by engineers. When the tires burst, the Japanese pedaled ahead on the metal rims. The clattering of the bicycle rims sounded to British troops like advancing tanks, which added to the chaos.

Not everything went the Japanese way. While Yamashita and his top brass enjoyed their strong intelligence, frontline Japanese officers had to make do with maps ripped from schoolbook atlases. Supply chains broke down.

On the Jitra line, Murray-Lyon’s 11th Indian Division dug in on a long front with too many gaps. The 15th Brigade’s line was 6,000 yards long, while 6th Brigade’s stretched 18,000 yards. Neither brigade could support the other. Amid pouring rain, Indian troops had only just enough time to string up a few strands of barbed wire and telephone lines before the Japanese arrived.

The Japanese attacked at 8 am on the 11th, forcing the 15th Brigade to withdraw in the pouring rain. The Japanese charged again with tanks, which panicked the Punjabis, most of whom had never even seen one, friendly or enemy. The Punjabis collapsed, leaving the 2/1st Gurkhas to absorb the Japanese attack. The Gurkhas were flanked and torn apart, retreating in small groups back to British lines.

The 6th Brigade did no better. When some of its outpost troops withdrew with seven anti-tank guns and four mountain guns, they reached a stream at Manggoi west of Jitra, whose bridge had been readied for demolition. The officer in charge of the bridge heard the column rumble down and blew the bridge, forcing the column to abandon its guns and trucks on the north bank.

“Seldom in the history of war can there have been such an unbroken skein of muddle, confusion, and stupidity,” wrote historian Arthur Swinson.

The Japanese drove on, moving by bicycle down paved roads most of the time and through jungle when necessary to ambush the British. On December 12, Percival’s two-day-old Order of the Day reached the rain-soaked and dispirited troops at Jitra: “The eyes of the Empire are upon us. Our whole position in the Far East is at stake. The struggle may be long and grim, but let us resolve to stand fast, come what may, and prove ourselves worthy of the great trust which has been placed in us.”

At noon, the Japanese 5th Infantry Division terrorized the 15th Brigade again. Soon troops and transports were streaming back amid disorder and rumors, and the 11th Division was on the run again, behind a screen of rearguard Gurkhas. The Indian troops, lacking antitank guns and training, as well as proper communications, decent maps, and time to prepare defenses, panicked at the sight of the riveted Japanese monsters.

The 11th Division retreated 15 miles in pouring rain, with units losing equipment and cohesion. The 15th Brigade emerged with only 600 men. Only one of its battalions, the 1st Leicesters, was able to hang onto its Bren carriers and mortars. Indian Sepoys tossed away their rifles as they fled. The 2/1st Gurkhas were down to one company. Japanese casualties were 27 killed and 83 wounded. The 11th Division was a wreck, having lost hundreds of men, as well as guns, equipment, transport, and even a set of maps with all the defensive positions marked. The Japanese took 3,000 prisoners. The attacking Japanese force had consisted of barely two battalions of infantry and a company of tanks.

Many of the Indians defected, becoming the nucleus of the Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army, which would guard POWs and fight alongside the Japanese in Burma. This collection of traitors was headed by Mohan Singh, a captain in the British Army, who was vaulted to the rank of INA general by the Japanese, who were delighted with their haul. General Matsui wrote, “The enemy troops have no fighting spirit … they are glad to surrender … they are relieved to be out of the war.”

British historians were harder, calling the Jitra disaster “the biggest disgrace to British/Indian arms since Chillianwala in the Second Sikh War of 1848.”

On the 13th, the 11th Indian Division streamed across the Sungei Kedah River near Alor Star. At dawn, Murray-Lyon watched his men retreat across parallel road and rail bridges. When the last Sepoy walked across, Murray-Lyon saw two Japanese motorcyclists headed toward them. Indian machine guns opened fire and killed the Japanese, and Murray-Lyon ordered the bridges blown. Explosives and smoke sullied the air, but when they cleared, the railway bridge was still standing. Before Murray-Lyon could show any rage, a railroad train came down from the north. Everybody relaxed, figuring the train’s weight would complete the job, but it jumped the gap in the rails and rolled on.

Engineers laid more mines and blew the bridge just as more Japanese arrived. They crossed the river and were immediately hurled back by the 2/9th Gurkhas. But Murray-Lyon decided his men were in no shape to fight and ordered a further 20-mile withdrawal to Gurun.

The troops staggered back, dazed and sleepless, to find no defenses. The 2/1st Gurkhas marched 64 miles in four days without rations. They hoped to have time to lay barbed wire and mines and get some sleep. Murray-Lyon figured it would take the Japanese three days to replace the blown bridges. It took the Japanese a day and a half.

By lunchtime on the 14th, three Japanese tanks and 12 truckloads of infantry charged down on the 6th Brigade at Gurun. This time the Indians had deployed their 2-pounder anti-tank guns and blasted the lead tank. The other two retired. Japanese infantry leaped from their trucks and charged the 5/2nd Punjabis. In two hours, they penetrated the exhausted Indians’ positions and sent the Sepoys scattering back. Brigadier W.O. Lay, commanding the 6th Brigade, recognized signs of incipient collapse and personally led a counterattack that stabilized the situation.

The victory, however, was temporary. Percival authorized another retreat that day, 60 miles south to the Perak River, with an evacuation of Penang Island, Britain’s oldest holding in the Far East.

The Japanese did not wait for the British to retreat to the Perak. Just after midnight, they opened up a mortar bombardment, and then bayonet-wielding infantrymen charged straight down the road. They stormed through the Punjabi lines and into the 2nd East Surreys, killing the battalion’s commanding officer and his staff. The Japanese charged on and destroyed 6th Brigade headquarters, leaving a gaping hole in the center of the line. Brigadier Carpendale of 28th Brigade took over, but the 11th Division was mangled further.

The 5/2nd Punjabis, one of the most “Indianized” units, was a mess. Newly trained NCOs and officers withdrew in panic. One officer was asked at pistol point why he had withdrawn without orders. Sepoys turned up at aid stations with self-inflicted wounds. It was the result of flinging poorly trained men into battle without support.

Worse, the planned evacuation of Penang also degenerated into panic. The British fled on the 16th, leaving the civilian population behind, along with intact power stations, radio stations, and collections of 24 motorized junks and barges, which the Japanese put to use.

At Alor Star, Japanese troops swarmed all over the captured base. Colonel Masanobu Tsuji found “a gift of bombs piled high, and moreover, in one of the buildings hot soup was arranged on a dining room table. Among the surrounding rubber trees 1,000 drums full of high-grade 90 octane petrol were piled high.” Japanese aircraft landed at Alor Star the day their troops seized it, refueled and rearmed with British aviation gas and bombs, and flew off into battle.

In the air, the RAF was hopelessly outmatched. Japanese bombers pounded the RAF almost into nonexistence. Surviving Brewster Buffalo pilots found their mounts unable to handle full-throttle climbs, high altitudes, or Japanese Zeroes. Battered squadrons pulled back to Singapore Island. The Dutch sent bomber and reconnaissance squadrons up from Java; they performed gallantly, but were also overwhelmed.

The Japanese stormed on, not bothering to consolidate or regroup. Despite looking like a badly wrapped parcel in his sloppy uniform, the Japanese soldier was hardy and tough. He could subsist on rice and salt fish for days.

By the 18th, Percival’s porous plans for Malaya’s defense had disintegrated. His air and naval forces were destroyed. His only reserve was the 9th Indian Division, holding the east coast, and the two untested brigades of the 8th Australian Division, which were covering Johore Province and Singapore Island. If he committed them to battle, the Japanese could land in Johore, cutting off Singapore. He had no choice but to keep the 11th Indian Division in the game, despite its disintegration, until the 17th Indian and 18th British Divisions arrived from India to reinforce them.

As the 11th fell back on the Perak River, Percival shuffled his limited deck. On the 17th, he assigned 11th Division the 12th Brigade, while the 15th Brigade absorbed the remnants of 6th Brigade to form a composite formation. Among the ad hoc units formed was the “British Battalion,” made of the 1st Leicesters and 2nd East Surreys, both battered in earlier fighting.

The next day, Duff-Cooper met with the senior commanders at Fort Canning. After hearing their woes, he sent a message to London to say that Malaya needed four fighter and four bomber squadrons and four infantry brigades. The 18th British Division, trained to fight in North Africa, was already being diverted to Malaya. Now a hundred Hawker Hurricane fighters were to be sent in as well.

After the meeting, Duff-Cooper took to the radio to buck up flagging morale. He described the evacuation of Penang in bizarre terms, saying all the Asian civilians had been withdrawn when they had not, which only enraged the leaders of the Chinese, Indian, and Malay communities, who protested to Sir Shenton Thomas.

Duff-Cooper opened his broadcast by saying, “I consider that one of my duties should be to keep in close and constant touch with the people of Singapore by speaking to them on the radio from time to time.” Actually, he never broadcast again.

This was a good thing, too. Morale in Singapore was collapsing. Nobody believed fatuous official communiqués about British troops “falling back to prepared positions” or “strategic withdrawals” that did not give actual place names. Civilians who wanted to know the Japanese pace of advance simply consulted the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank’s advertisements that daily listed branches closed “until further notice.”

Aside from air raids, the only signs of war in Singapore were the endless trail of wounded men coming off trains from the front who jammed up the hospitals, and official confusion and idiocy. Deputy Municipal Engineer Gilmore was ordered to dig trenches six feet wide and three feet deep on sports grounds to prevent Japanese aircraft and gliders from landing. He rounded up several hundred coolies to do so. When they were half done, another official said the trenches had to be redug—straight trenches would offer no protection in an air raid.

Gilmore ordered his men to redig the trenches, which created vast mounds of earth. Another official told Gilmore to have that carted away so it could not be used by paratroopers as landing grounds. After Gilmore did so, up came the health authorities to warn that the trenches could become breeding grounds for mosquitoes and they had to be filled in. After some argument, they agreed to have them half-filled. Away went the coolies to haul back the earth to fill in the bottom two feet of the trenches.

On the docks, supplies piled up because there was a shortage of labor to unload ships. Nobody could agree on rates of pay for coolies.

The Army ran into official idiocies, too. The secretary of a golf club refused the Army permission to turn it into a strongpoint until he had called a special committee meeting. Another officer was refused permission to cut down a row of trees to improve his field of fire on the outskirts of Singapore until he had produced written authority.

When Brigadier Ivan Simson, the chief engineer, went to see Maj. Gen. Gordon Bennett about building antitank obstacles, the peppery Bennett did not want to discuss the subject at all. Bennett said, “I have little time for these obstacles … preferring to destroy tanks with anti-tank weapons.”

Percival tried to restore order. It was not easy. All the brigadiers of 11th Division were casualties, and Lt. Col. H.D. Moorhead took over 15th Brigade while Lt. Col. W.R. Selby gained 28th Brigade. Percival sacked Murray-Lyon and put 12th Brigade’s boss, Brigadier A.C.M. Paris, in charge. Lt. Col. Stewart was promoted from command of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders to command of 12th Brigade.

Up front, the British retreat continued. A British officer wrote, “It can’t go on like this. The troops are absolutely dead-beat. The only rest they are getting is that of an uneasy coma as they squat in crowded lorries which jerk their way through the night. When they arrive they tumble out and have to get straight down to work. They are stupid with sleep, and have to be smacked before they can connect with the simplest order. Then they move like automatons or cower down as a Jap aeroplane flies 200 feet above them.”

Japanese snipers infiltrated through British lines to harass their rear areas, wearing rubber shoes to avoid making noise, keeping the defenders exhausted. One British brigadier went without sleep for 36 hours straight.

At Lake Chenderoh Power Station, a group of 5/2nd Punjabis would not go on night patrol, as the Japanese were letting off squibs (firecrackers). Their colonel told their captain, “There was no known case of squibs causing loss of life, go out and stall the Japanese.”

The British defenders had other problems, too. Humidity and rain corroded radio sets and wrecked communications. Equipment lost in the retreats could not be replaced.

In Singapore, leadership squabbles continued. Duff-Cooper had Colonial Secretary Stanley Jones fired. Then he arranged for the replacement of Brooke-Popham with the younger General Sir Henry Pownall, a veteran of Dunkirk and a more able figure. Pownall arrived on December 23 and took over four days later.

Despite this, Duff-Cooper continued to bumble, irritating military commanders and civilians alike. He knew nothing of Malaya, even suggesting that the Army burn down all 300 million gum trees to deny rubber to the invader.

Simson was not allowed to build entrenchments on Singapore Island. He complained to Percival, asking why he could not build breastworks. “I believe that defenses of the sort you want to throw up are bad for the morale of troops and civilians,” Percival answered. Simson was horrified and felt his blood run cold. He answered, “Sir, it’s going to be much worse for morale if the Japanese start running all over the island.” Actually, Percival was just echoing Brooke-Popham’s line. But after Brooke-Popham left, Percival still did not build entrenchments.

Instead, on December 30, Duff-Cooper put Simson in charge of civil defense, wasting the chief engineer’s talents.

Meanwhile, the Japanese continued their advance, heading for the Perak River. The Guards Division entered the fray at last, hooking through thick country east of Kuala Kangsar and across the Perak. Yamashita, relying on his psychological edge, ordered his commanders, “I don’t want them [the enemy] pushed back. I want them destroyed.” Yamashita had another reason to hurry. His lengthening supply line meant that he was running short of artillery ammunition.

On the 28th, the Japanese scattered a counterattack by the 4/19th Hyderabads and blasted through the usually reliable 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. For the only time in the campaign, Argyll officers had to draw their pistols to stop a retreat. The Scots regrouped and fought hard, but it was not enough. Colonel Watanabe’s 11th Regiment, using small craft captured at Penang, landed south of the Perak River. The British abandoned Ipoh and continued to retreat.

On December 30, the War Cabinet in London appointed Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell as Supreme Commander of the Australian-British-Dutch-American Command area, which included Malaya. He received the telegram while pig-sticking with his family at Meerut, 40 miles from Delhi, India. When Wavell read the telegram, he said, “I have heard of having to hold the baby … but this is twins!” Pownall was appointed his chief of staff, and the post of Commander in Chief Far East was abolished.

Wavell brought a long record of literary achievement and combat service to his new task, including overseeing the British victories over the Italian Army in North Africa in 1941. He also oversaw defeats in Libya, Greece, and Crete after that.

By December 31, the battered British-Indian 3rd Corps had fallen all the way back to Kampar, 25 miles south of Ipoh. Once again, Heath deployed his troops for battle, and Matsui decided to launch two prongs, the 11th Regiment down the road with the 42nd Regiment detouring to the west.

On New Year’s Day, 1942, the Japanese attacked. Matsui’s plan disintegrated due to the terrain, the 42nd Regiment floundering in the swamps. However, his artillery barrage weakened British defenses, and his frontal attack went in against the British Battalion.

“The [enemy] attacks were made with all the well-known bravery and disregard of danger of the Japanese soldier. There was dogged resistance in spite of heavy losses, by the men of the British Battalion and their supporting artillery, and finally, when the enemy had captured a key position and the battalion reserves were exhausted, there was a charge in the old traditional style by the Sikh company of the 1/8th Punjab Regiment,” an Indian Army historian wrote. “The charge went in through heavy Japanese mortar and machine-gun fire, killing the Indian company’s commander. The charge re-captured the ground, but only 30 Punjabis were left after the battle.”

While this battle raged, Yamashita, using shipping captured at Penang, hurled a landing force 20 miles south of the British lines at Utan Melintang. The British were again forced to withdraw.

The same day, the Japanese landed at Kuantan on the east coast and chased the 22nd Indian Brigade off the Kuantan airfield, putting the Japanese 160 miles from Singapore. Once the airfield was taken, the Japanese moved bombers and fighters to the captured strip, which, like many other captured RAF bases, was full of intact British stores, abandoned in panic and retreat.

Two days later, the 45th Infantry Brigade landed at Singapore. Percival found them “very young, unseasoned and undertrained, and straight off the ship after their first experience at sea.” Part of the 17th Indian Division, the 45th and 44th Brigades had just finished training at Poona in India. Trained and equipped for the North African desert, the brigades lacked compasses and wireless sets. Indian Army Director of Training Brigadier Punch Cowan said that without further training, the 17th was only good for fighting against a second-class enemy. Despite this, they were rushed to Malaya.

In Singapore, Japanese air raids became a daily event. The constant bombing frightened coolies, and British troops had to work as stevedores. At least 150 people per day died from the bombs, and martial law was declared. The Army was finally able to place AA guns on the golf club’s property, but there was still dancing every night at the Raffles Hotel. The Straits Times wrote, “Everybody in this country seems to have been lulled into a false sense of security by confident statements regarding continuous additions to our armed might. The only people who have not been bluffed by them are the Japanese.”

Yamashita launched another west coast amphibious flank maneuver on January 2, when Guards Division detachments landed at Kuala Selangor and Port Swettenham. This time the British hung on, and the Japanese could not gain a foothold at Kuala Selangor until January 4.

Percival ordered the Royal Navy to repulse the landing. However, Rear Adm. Geoffrey Layton, who took over after Admiral Phillips went down with Prince of Wales, had already withdrawn his surviving cruisers and destroyers to Ceylon. His last message—“I have gone to collect the Eastern Fleet. Keep your heads high and your hearts firm until I return”—had only damaged morale for the remaining sailors. All that was left were two destroyers and two motor launches.

With the Navy unable to cope, the RAF defeated, and the Army in retreat, Wavell flew to Singapore to inspect the situation. His first move was to deliver a telegram to Duff-Cooper that sent the politician home. Duff-Cooper was happy to go, having been overtaken by events. Even so, Duff-Cooper described Simson’s complaints to Wavell, and the Field Marshal was astonished that fortifications had not been built. Wavell initially thought that Simson was a lying troublemaker, paying off an old score against Percival.

Wavell summoned Percival, and the two flag officers went to Singapore’s north shore. Wavell was stunned to see that Simson was right. “Very much shaken,” as he wrote in a letter, Wavell asked Percival why nothing had been done, and also for an explanation “for his neglect.” Percival gave the stock answer about morale. Wavell repeated (probably unknowingly) Simson’s words about the Japanese pouring onto the island being worse for morale. Wavell ordered Singapore’s defense team to start digging entrenchments.

Wavell’s anger had some impact. Sir Shenton Thomas sent out a circular to the Malayan Civil Service: “The day of minute papers has gone. There must be no more passing of files from one department to another, and from one officer in a department to another.” The Straits Times acidly commented on this: “This announcement is about two and a half years late.”

The 11th Division now retreated to the Slim River to dig in. Under constant bombing and strafing, the troops had no rest. “The battalion was dead tired,” wrote Colonel Deakin of the 5/2nd Punjabis. “Most of all the commanders, whose responsibilities prevented them from snatching even a little fitful sleep. The battalion had withdrawn 178 miles in three weeks and had had only three days’ rest. It had suffered 250 casualties of which a high proportion had been killed. The spirit of the men was low, and the battalion had lost 50 percent of its fighting efficiency.”

On January 5, Deakin wrote, “I found a most lethargic lot of men who seemed to want to do nothing but sit in slit trenches. They said they could not sleep because of the continued enemy air attacks. In fact, they were thoroughly depressed. There was no movement on the road, and the deadly ground silence emphasized by the blanketing effect of the jungle was getting on the men’s nerves.… The jungle gave the men a blind feeling.”

That day the Japanese attacked again. This time the 4/19th Hyderabad’s Bren guns chewed up the attack, leaving 60 dead on the field. At 3 am the next day, under a late-rising moon, the Japanese sent in tanks and lorried infantry. The tanks were stopped by mines, and the infantry leaped out of the trucks to attack. The British charged back with bayonets, knocking out three tanks. The Japanese regrouped and flanked the British via some loop roads overgrown with bushes. Tanks rumbled over the bushes and smacked into the Punjabis’ Reserve Company.

“The din … baffles description,” wrote Deakin of the Punjabis. “The tanks were head to tail, engines roaring, crews screaming, machine-guns spitting, and mortars and cannon firing all out. The platoon astride the cutting threw grenades, and one tank had its track smashed by anti-tank rifle. The two anti-tank guns fired two rounds one of which scored a bull, and then retired to the Argylls’ area. One more tank wrecked itself on mines.”

Battered, the Japanese found another loop road and drove around the Punjabis. The Indians tried to warn the Argylls by phone, but Japanese tanks cut down the phone line just after sappers set it up. Six miles north of the Slim River Bridge, 30 Japanese tanks attacked the Argylls and 3rd Indian Hussars, equipped with armored cars that mounted Vickers machine guns and Boys’ antitank rifles. The crews had never been trained on either weapon. The Japanese tanks knocked out the armored cars and rolled on, grabbing the bridge before anyone could blow it. The disgusted Scots withdrew while the Japanese slammed into the Punjabis from behind, forcing them to withdraw as well.

Deakin was enraged as his outfit collapsed around him. “How many men of the Battalion were killed and wounded and how many took to the jungle was not known and perhaps will never be known. Be what it may, the battalion had disintegrated and had failed to stand and fight to the last man. Whether or not an Indian Battalion can be expected to stand against an overwhelming number of tanks with practically no anti-tank defenses is not a question for decision in the War Diary,” he wrote.

Deakin added, “It must be admitted at once that the Battalion had been disappointing and had failed to come up to expectations as a fighting unit and at times had showed a great lack of collective and individual courage. The Indian Commissioned Officers except for Lt. Chadda had failed to show leadership and that spirit of self-sacrifice and courage which is essential to Indian troops. Whether British Officers would have done so under similar conditions cannot be said, but the two in the Battalion who had the opportunity, did so.”

There were more failures. Many of the best men had died in earlier battle. There were no replacements. The men had been fighting day and night for a month without rest against an enemy that attacked constantly and under continuous bombing.

The speed and violence of the Japanese assaults kept the 11th Division off balance. Worse, the Indians relied on phone communications, which kept breaking down when Japanese troops knocked down the poles.

The Japanese roared on, brushing past the 2/9th Gurkhas and into the 2/1st Gurkhas, catching them in column of march and scattering them. Then the tanks shot up two batteries of artillery parked by the road and reached Slim River Bridge.

The defense there consisted of a troop of Bofors antiaircraft guns, which opened fire on the advancing tanks to no avail. The 40mm shells bounced off the tanks’ hulls, and the Japanese machine guns wiped out the Bofors gunners. Then the tanks crossed the bridge and drove south two more miles. There they met up with the 155th Field Regiment of Royal Artillery. Both sides were surprised to see each other, but the British 4.5-inch guns blasted open the lead tank 30 yards away, finally stopping the Japanese advance for the moment.

The battle virtually destroyed the 12th Indian Brigade. The reliable Argylls were down to a hundred men. The Japanese captured or destroyed vast quantities of British guns and transport. Percival was forced to continue the withdrawal, admitting that the “11th Indian Division had temporarily ceased to exist as a fighting formation.”

Percival’s only weapon at hand was Gordon Bennett’s 8th Australian Division. Many of the Australians had only just learned how to fire their rifles. The Australian artillery consisted of pieces captured from the Italians in Libya and French 75s captured in Syria, and the crews had not trained on them. “We were going into action with a 2-pounder, which we had never fired, except in theory,” wrote one antitank gunner.

The Malayan apathy was not broken either. An Army medical unit drove up to the bungalow on a rubber plantation to set up an aid station, and the manager ordered the military out for trespassing on private property. A formal complaint would be sent in for this breach of regulations. The irritated British officer commanding the detachment said, “We’ll be leaving soon, and the Japanese will be arriving. Perhaps they’ll listen to your complaints.”

Yamashita was complaining, too, to his diary. Reports of ecstatic press coverage of his victories had come from Tokyo, which did not please the general. He was still one of Tojo’s enemies and feared the prime minister would move to eliminate potential rivals, especially successful ones.

Worse, Yamashita and his staff officer, Tsuji, were at loggerheads. The latter opposed Yamashita’s flanking amphibious moves and had spoken up to support troops who had committed rape and murder in Penang. Yamashita yelled at Tsuji, which cost the staff officer face. When Tsuji offered his resignation, Yamashita overrode it. The angry Tsuji was now sending secret messages back home to Tokyo denouncing Yamashita. Nor could Yamashita trust his boss, Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, in Singapore, also an old rival.

More prosaically, victory had come with strains. The 25th Army had outrun its supply lines. The men were hungry, sore, sick, and short of ammunition. They were still going on captured British ammunition and rations.

Yamashita filled up his diary with angry comments. January 1: “I can’t rely on communications with Terauchi and the Southern Army, or on air support from them. It is bad that Japan has no one in high places that can be relied upon. Most men abuse their power. They have no conscience and their only aim is to grab even more power.”

When a delegation from Tokyo visited on January 9, Yamashita wrote, “Five staff officers have arrived from Tokyo. I hate them. That bloody Terauchi! He’s living in luxury in Saigon with a comfortable bed, good food, and playing Japanese chess.”

Yamashita also blasted his juniors, particularly the Imperial Guards Division. “[Nishimura] has wasted a week by disobeying my orders.” Matsui’s 5th Division: “On the 6th I ordered them to carry out a flanking movement and so trap the enemy and crush him. But my orders weren’t obeyed. I am disgusted with the lack of training and inferior quality of my commanders.” On January 8: “The battalion commanders and troops lack fighting spirit. They have no idea how to crush the enemy.”

He had serious complaints about issues that would damage the Japanese in battles for years to come. Japanese troops chattered as they moved through jungle; they lost their way; many officers and men couldn’t read maps; infantry-artillery coordination was poor; patrolling was weak.

To be sure, Yamashita was worn out himself, and a staff officer said, “Our general is near to mental explosion.” On January 11, he cheered up, as the British withdrew from Malaya’s capital, Kuala Lumpur, leaving behind a fairly intact airfield, more supplies, burning oil tanks, and brand new maps of Singapore in a railway car.

All day on the 10th, the British pulled out of Kuala Lumpur, with exhausted troops riding in commandeered private cars, motorcycles, 11 steamrollers, and even two fire engines. Chinese, Malay, and Indian natives watched in silence as the once omnipotent white men fled in defeat and exhaustion. The lesson was not lost on Asia’s population.

Yamashita was pleased but wasted no time in victory parades. He scribbled out his appreciation of the situation for his three divisional commanders. The next British defense line would likely be the Muar River. To forestall this, the Imperial Guards would concentrate at Malacca and head south, joined by the 18th Division, which was just landing. After a rest, the 5th Division would continue down the trunk road.

On the 13th, another convoy arrived at Singapore, bringing 51 Hurricane fighters, victors in the Battle of Britain. Already inferior to the latest types of German Me-109 fighters, the Hurricanes were hopeless against the Japanese Zeroes and Oscars that dominated Malaya’s skies. The convoy only brought in 24 Hurricane pilots. Weary Buffalo pilots would have to retrain on the new planes.

A convoy on the 22nd brought in 1,900 Australian reinforcements, including the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion and the 18th British Division’s 53rd Infantry Brigade. The 18th had no time to train on their troopships during the 11-week voyage or once in Malaya. The young men, all second-line Territorials, were shocked by the destruction and panic they saw when they arrived. They did not even have tropical clothing. The Australians included men who had only had seven days of serious training. Many had never fired a rifle.

With Japanese guns 100 miles from Singapore, Percival told his troops they were getting their “second wind” and urged his exhausted and poorly trained men to fight like guerrillas. The Australian 27th Brigade was sent north to join the 9th Indian Division and the newly arrived 45th Indian Brigade, under Brigadier H.C. Duncan. All of this group would be designated Westforce. They would hold northwest Johore.

The other main force, the Australian 22nd Brigade and 11th Indian Division, under 3rd Corps, would be Eastforce and would hold the rest of Johore all the way to the east coast of Malaya. Once the 18th British Division had formed up, it would relieve the Australians and the 11th Indian Division, and they would be held back as a counterattack force.

There were more shuffles, as Billy Key took over the 11th Indian Division from Maj. Gen. Paris, giving that battered outfit its third commanding officer in two months.

On paper, the plan looked fine, but there were plenty of weaknesses. The 11th Indian Division was exhausted. It was unwise to split up the Australians. Duncan’s 45th Indian Brigade was being hurled into a critical battle without any jungle training. Even Winston Churchill pointed out that the only vital point in Malaya was Singapore Fortress, and the battles being fought up north were only weakening the island’s defenses.

Nonetheless, the orders were cut, the motorcycle dispatch riders shot off, and the Australians entered battle at Gemas, facing the tough Japanese 5th Infantry Division. Bennett believed in ambushes, so on January 14th, the 2/30th Australians set one up on Gemas’s main road just east of the bridge there. Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Galleghan told his 2/30th officers, “The reputation not only of the AIF in Malaya, but of Australia, is in the hands of this unit.”

At teatime, a 250-man company of the Mukaide Detachment (a battalion of infantry on bicycles, supported by tanks, guns, and engineers) came down the road. Just as they passed, the Australians blew the bridge, trapping the Japanese, and opened fire with everything they had, chewing up the Japanese attack. The theory worked. “The charge hurled timber, bicycles and bodies skyward in a deadly blast,” the battalion reported. B Company’s commander said, “The entire 300 yards of the road was thickly covered with dead and dying men—the result of the blast when the bridge was blown up and the deadly fire of our Bren guns.”

The next day, the Japanese answered the ambush by bombing the Australian positions and attacking again. The Australians opened up and set the first tank afire, disabled the second, and forced the third to be towed away. Four more tanks lumbered up, and the Australian mortars and antitank guns hit the first, disabled the second, set the third ablaze, and wrecked the fourth when a mortar bomb entered its narrow turret. The 2/30th suffered 17 killed, nine missing, and 55 wounded, but took a heavy toll of the Japanese before withdrawing.

The RAF made an appearance on the 16th, with 453rd RAAF Squadron’s 12 Buffalo fighters zooming over the Japanese columns, strafing them heavily. The Japanese retaliated by sending 27 bombers to pound the RAAF base at Sembawang. The bombing left the British with 74 bombers and 28 fighters against 250 Japanese bombers and 150 fighters in Malaya.

Matsui, irritated, sent in a full division attack, while Nishimura’s Imperial Guards hit the new 45th Indian Brigade on the Muar River near the coast on the 15th. The Imperial Guards were in luck. When they attacked the 7/6th Rajputana Rifles, they found them, per Bennett’s orders, north of the riverline instead of south of it. The Guards chopped up two Rajput companies and then the 4/9th Jats and 5/8th Garwhals. The 45th Brigade’s Brigadier Duncan personally led a bayonet charge and was killed. The 45th Brigade collapsed.

Bennett put in the 2/29th Battalion at Bakri to hold the line and found Indians racing back from the frontline on foot and in trucks. The Aussies fired at the Indian tires to stop the flight, and the Indians thought they were under Japanese attack, which set off some unfortunate “blue-on-blue” firefights. The newly established Australian position could not hold. Bennett, stunned by the failures, despaired.

As the Australians came tumbling back on January 20, Lt. Col. C.G.W. Anderson, commanding the 2/19th Battalion, found himself in command of a collection of Australian and Indian troops, including the bulk of the 45th Indian Brigade, which had been torn apart behind Japanese lines. With considerable calm, Anderson led his mixed group out through enemy lines, under machine-gun and air attack. The “Anderson Column” was trapped five miles behind enemy lines and headed east toward Parit Sulong.

There, Anderson received a Japanese surrender demand. If Anderson gave up, the Japanese would let ambulances with wounded through. Anderson refused the demand. The RAF tried to help, as two Fairey Albacore biplane torpedo-bombers paradropped food and morphia to the column. At 9 am, Anderson found he could not move his vehicles across the Parit Sulong Bridge. He ordered the destruction of his Bren carriers, 25-pounder artillery, and vehicles, and had his men withdraw through the swamps and jungle. He was forced to leave behind 110 wounded Australians and 40 Indians who could not travel. When the Japanese caught them, they stripped the wounded men and subjected them to beatings, while denying them water and medical attention.

When a Japanese camera team appeared, the Japanese guards displayed water bottles and cigarettes, pretending to give them to the POWs while the cameras clicked. As soon as the camera crew was gone, the Japanese threw away the water and resumed bayoneting and shooting as many as 150 POWs. Two of them faked death and were able to escape to British lines, bringing evidence that would ultimately send the Guards Division’s commander, Nishimura, to the gallows.

Anderson and his 900 survivors, exhausted, hungry, and shelled, plodded on until the 23rd, when they reached 2/29th’s lines. Anderson earned a Victoria Cross for his leadership and gallantry. The Japanese had lost a company of tanks and a battalion of men to Anderson’s band, and their account paid tribute to the bespectacled Australian and his men. Anderson later commented, “The well-trained Australian units showed a complete moral ascendancy of the enemy. They outmatched the Japs in bushcraft and fire control … [and inflicted] heavy casualties at small cost to themselves. In hand-to-hand fighting [the Japanese] made a very poor showing against the superior spirit and training of the AIF.”

On January 19, Wavell warned Churchill that Percival had no plan to withdraw to and defend Singapore Island, and he believed that the island could not be held. Churchill retorted with typical rhetoric, “I want to make it absolutely clear that I expect every inch of ground to be defended, every scrap of material of defenses to be blown to pieces to prevent capture by the enemy, and no question of surrender to be entertained until after protracted fighting among the ruins of Singapore City.” It was the first use of the word “surrender.” Churchill also ordered the moat to be fortified, using the “entire male population” to create defense works.

However, Maj. Gen. Sir John Kennedy, Director of Military Operations at the War Office, pointed out to the Chiefs of Staff that Singapore Island had never been considered defensible against close attack. The channel was narrow, mangrove swamps impeded defensive fire, and the airbases, water supply, and other vital installations were all within artillery range from the mainland. Kennedy recommended evacuation from Singapore, not defense.

The next day Wavell flew to Singapore. Percival outlined his three-column plan to withdraw to Singapore Island. Percival divided the 20-by-11 mile island into three sectors, the west to be held by the Australians, the north by the 18th British, and the south by the Indian formations. Wavell was furious to see that Singapore’s north shore was still unfortified.

The 44th Indian Brigade arrived on the 24th. They consisted of 7,000 raw recruits, with very few NCOs. Percival held them and the Australian machine-gunners in reserve, writing, “Excellent material they were, but not soldiers as yet. I have no wish to blame the authorities, either in India or Australia, for sending these untrained men. After all they had no better to send.” The rest of the 18th Division arrived on the 29th on American troopships.

In the air, things were getting worse. The 50 Hurricanes had been uncrated at last, but there were only 24 pilots trained on them. The Hurricanes made their debut over Singapore on January 20 and shot down eight Japanese bombers. The Japanese slammed the Hurricanes back the following day, flying rings around the British, splashing five Hurricanes. Japanese bombers pounded Kallang, killing New Zealand Pilot Officer L.R. Farr, an Auckland clerk, when a bomb hurled him into a petrol dump. The 243rd RNZAF Squadron was left with one serviceable Buffalo. Percival asked the RAF to attack the Japanese airbases, but they had little success. Meanwhile, the Japanese continued to blast Singapore, causing up to 2,100 civilian casualties in January alone.

Reality was still not sinking in on Singapore Island. Despite the hospitals jammed with wounded men and the constant bombing, the ruling British talked in their clubs about the tide of war turning in Johore. The Chinese were more realistic. They terminated the chit system, forcing thousands of white men to come up with cash to buy food. That led to a run on food stores. However, authorities were finally beginning to realize the worst. Thousands of European women and children were safely evacuated on the troopships that brought the 18th Division to Singapore.

The Japanese relied on ferocity and ruthlessness to make up for their lack of transport and weak logistics. They commandeered rice and food from villages and drank from streams. They impressed civilians to carry ammunition and stores and left wounded and sick men behind.

The Royal Navy tried to intervene with destroyers HMS Thanet and HMAS Vampire, attacking a Japanese convoy off Endau on the east coast. They ran into three Japanese destroyers, which immobilized and sank Thanet, driving off Vampire. The Japanese unloaded a construction team at Endau, which built a forward fighter base.

On the 23rd, Percival ordered his men to start withdrawing to Singapore, and a shocked Australian Prime Minister John Curtin cabled Churchill: “After all the assurances we have been given, the evacuation of Singapore would be regarded here and elsewhere as an inexcusable betrayal.”

As British forces withdrew, disasters continued. The 22nd Indian Brigade was cut off by Japanese forces and 8th Indian Brigade’s withdrawal. Brigadier Lay, commanding 8th Brigade, blew a bridge that was Brigadier G.W.A. Painter’s 22nd Brigade’s retreat route, trapping them. As the 22nd fell back, they took heavy casualties. Sikhs threw away their rifles and surrendered. By February 1, the 22nd was down to 350 men, without ammunition, and surrounded. Painter had to surrender. Lay was fired.

Percival cabled Wavell, “Consider general situation becoming grave. With our depleted strength it is difficult to withstand enemy ground pressure combined with continuous and practically unopposed air activity. We are fighting all the way but may be driven back into the Island within a week.” A later telegram warned Wavell that Johore could only hold for four more days, and fighter strength was down to nine.

Meanwhile, the exhausted British and stunned Australians tumbled back. The Australians were amazed that their brief and successful appearance on the battlefield had only led to more retreats. Worse, they had not trained in withdrawals, and their retreat became disorganized. Galleghan complained, “One of the mistakes made in our training was that they never let us do withdrawal exercises.”

War correspondent O.D. Gallagher told his Daily Express readers: “Major General Bennett often told war reporters in interviews that his men would never retreat because they did not know how to retreat—they had not been trained to retreat. The spirit was admirable, but the wisdom of the decision doubtful. How could the Australians be expected to make an orderly, fighting withdrawal if such a maneuver had not been included in their training?”

So the retreat continued. On January 24, the tough 5/11th Sikhs showed what could be done when they launched a bayonet charge into the Japanese, killing hundreds. Japanese troops, stunned that their enemy was fighting back, dropped their rifles and fled.

But it was not enough. On January 26, the RAF hurled its remaining Vickers Vildebeestes against another Japanese landing at Endau, with Buffalo and Hurricane fighter escort. The Japanese lost 13 fighters, but the RAF lost 11 Vildebeestes, two Hurricanes, and a Buffalo. Two Japanese transports were hit, but the landing went in anyway. On January 27, the RAF started pulling out of Singapore. Only 21 of the original 51 Hurricanes sent to Singapore were still available. Reconnaissance work was being done by Flt. Lt. Dane, a Malaya resident, and his pals from local flying clubs in Gypsy Moths and other civilian planes.

On the 28th, the Japanese attacked the 27th Australian Brigade. The 2/26th and 2/30th battalions, joined by the British 2nd Gordons, stood off the assault and withdrew at nightfall. Percival met with Heath and his staff. There were too few reserves to fight for Johore. The evacuation to the island would be completed by the morning of January 31.

The next day, the 27th Australian Brigade fell back to Milepost 31. Major General A.E. Barstow, commanding the 9th Indian Division, rode a trolley up to the front to check on the situation, came under close-range Japanese fire, slid down the side of an embankment, and was never seen again. The 22nd Australian Brigade held the four-mile perimeter around Johore Causeway as the 3rd Indian Corps streamed back. When they were gone, the Australians withdrew. The final perimeter of the Johore Causeway was held by the toughest outfit the British had left, the 2nd Argylls, down to 90 men, five officers, and a padre.

Exhausted British forces streamed over the causeway, hoping they would rest in an impregnable fortress until the Royal Navy came to rescue them. They were stunned to find no defenses built and the Malay mentality of apathy still in force.

Yet hopes remained high. Men volunteered to join the Argylls, and it was fattened up to 250 men with returned wounded men, police officers, and Royal Marines from the sunken ships. There was food for six months. Some 9,000 cattle and 125,000 pigs had been brought from Johore. The island’s three reservoirs guaranteed 17 million gallons of water per day.

By 5:30 am on January 31, the last British troops had withdrawn over the 1,100-foot long causeway. Percival gave the order and the 2nd Argylls marched over the causeway, heads high and bearing steady, led by their two surviving bagpipers, playing “A Hundred Pipers” and “Hielan’ Laddie.” The Japanese did not appear to interrupt this defiant display. The last British soldiers to cross the causeway were Colonel Stewart, back as battalion commander, and his batman.

After Stewart crossed onto the island, Royal Engineers punched the buttons and the 70-foot-wide causeway, including its road, rail, and water lines from the mainland, blew up in a pile of smoke. A 70-foot gap opened in the causeway and water flooded through. The siege of Singapore had begun.