By Flint Whitlock

The night of June 5, 1944, and the morning of June 6 were without a doubt some of the most pivotal hours in the history of the 20th century.

In the vanguard of the massive Allied effort to wrest the European continent from the murderous grip of Nazi Germany, the Western Allies had crafted Operation Overlord, a combined air and sea invasion that relied on secrecy, stealth, surprise, deception, and violence to punch through German defenses along the northern coast of France.

The planners at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) had always seen the invasion being launched with a prelude of parachute and glider forces. These airborne troops would be dropped and landed behind enemy lines along the Normandy coast to seize key objectives such as crossroads and bridges to prevent the Germans from counterattacking the seaborne invasion force.

Not only that, but the planners were counting on such airborne forces being able to sow confusion among the enemy ranks, cause the Germans to look over their shoulders, and perhaps launch their counterattacks in the wrong direction, thus giving the amphibious troops a few precious hours more to come ashore.

To help their amphibious forces land, the British would land a force of paratroops and glider-borne soldiers at the easternmost edge of the invasion area to knock out gun positions that posed a threat to the debarking troops at Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches and seal off the area from counterattacking German units.

The Allies’ western invasion beachheads were code-named Omaha and Utah; no airborne or glider troops were scheduled to drop behind Omaha, but, because it was the westernmost, Utah Beach, at La Madeleine, was deemed to be the most vulnerable. To secure it, over 13,000 men of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions would be inserted.

La Fière Bridge

Shortly after midnight on June 6, as 821 C-47 Skytrain transport planes dropped advance elements of the divisions, the situation began to go wrong in a hurry. Quickly recovering from their surprise, the Germans on the ground began filling the night sky with antiaircraft shells. The planes, flying in formation, made perfect targets, and the paratroopers inside began bailing out far from their intended drop zones.

Some of the 82nd soldiers, and a few of the 101st as well, came down right over the vital crossroads town of Sainte-Mère-Église, while other groups of paratroopers ended up on the west side of the Merderet River and its flooded adjacent fields, where they could do little good.

Battles are often fought in places that had no prior historical significance. They are accidents of geography, imbuing importance to some otherwise insignificant piece of real estate. So it was with a place called La Fière, a mile west of Sainte-Mère-Église.

La Fière was not so much a village as it was (and is) a collection of buildings—the Manoir de la Fière, then owned by the Leroux family—and a small stone bridge over the Merderet River, usually a small, meandering stream. It is an undistinguished, ordinary looking bridge that resembles scores of other stone bridges in Normandy. In fact, it could be a miniature replica of the stone bridge over Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg, Maryland. But great events often imbue ordinary-looking places with historic importance. And, just as Ambrose Burnside’s Union troops and Robert Toombs’s Confederate forces imbued the Antietam Bridge with importance on September 17, 1862, and hallowed the ground with their blood, so, too, did the Americans and Germans at this small stone bridge over the Merderet.

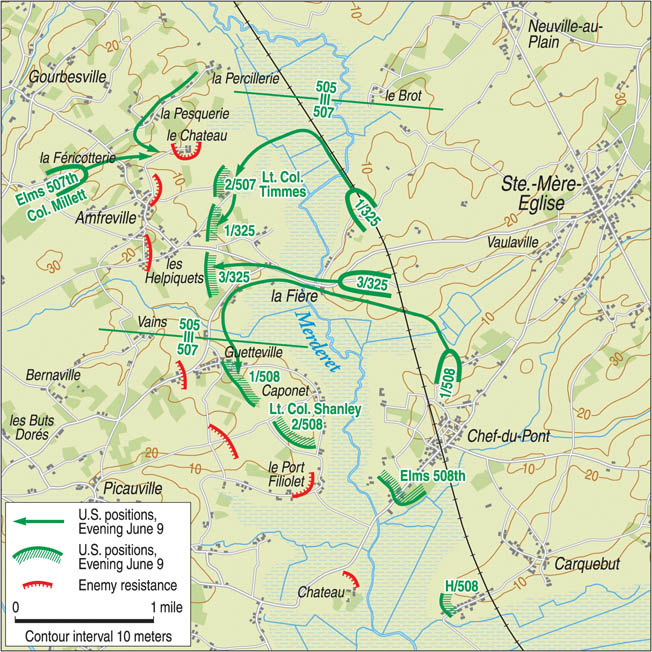

Located on one of the few routes that German forces to the west of Sainte-Mère-Église could use to assault Utah Beach, the La Fière bridge assumed an importance far out of proportion to its modest size. To seize it, SHAEF had originally assigned two 82nd regiments: Colonel William Ekman’s 505th, which would grab the east end, and Colonel George Millett’s 507th, which was supposed to seize the western side.

Flawless Landing For the 82nd’s 505th

That, of course, was the plan, but like most of the other plans that morning, this one began unraveling even before it got under way. Regiments, battalions, companies, and platoons had been blown like autumn leaves all over Normandy; almost no troops had come down on their designated drop zones. Radios had been smashed or lost in marshes that were not supposed to exist. Maps were on the bodies of leaders drowned in the swamps or hanging dead from trees. Weapons, ammunition, and other vital supplies were safely inside equipment bundles that had landed who knows where.

To top it off, enemy forces were stronger than anticipated. Yet, the airborne troops had been taught to improvise, to do the best they could with what they had, to take charge of leaderless soldiers and accomplish the mission no matter what the cost. And, out of the confusion of the drop, that is exactly what they began to do.

Fortunately, the 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) commander, Major Frederick Kellam, and most of the rest of his battalion, performed a rare feat on D-Day morning: they landed on time and on the correct DZ.

Sergeant Robert M. Murphy, A Company, 505th PIR, 82nd Division, related, “My company assembled almost 98 percent of our men under the leadership of our hard-nosed first lieutenant, John J. “Red Dog” Dolan, so named for his red hair and tenacity. When I met up with Dolan, everyone seemed exuberant, high spirited and ready for action. There is a peculiar elation, a feeling that paratroopers experience after a combat jump. Their chute has opened, and they’ve reached the ground alive.”

Once Dolan had assembled the majority of his company, about an hour before dawn, he struck out from DZ “O” toward La Fière manor and bridge. Dolan was supposed to seize and hold the bridge—an assignment that initially did not look too tough.

“Ground Here Probably Soft”

The bridge stands just a grenade’s throw west of the manor buildings. Beyond the bridge was a swamp caused by the flooding of the Merderet, 1,000 yards wide at its narrowest; the elevated causeway between the farm and the tiny hamlet of Cauquigny, a kilometer to the west, was the only dry passage either side could use. Once Dolan’s men captured the buildings that overlooked the bridge and causeway, they would have a ready-made fortress from which to defend them.

The number of enemy troops at this position was unknown at the time (it turned out to be only 28 men initially), but it was assumed that the Germans were guarding every bridge, no matter how small, and Dolan knew he needed to find out if the enemy was in or around the farm buildings. The only way to do that was to send a patrol into harm’s way.

Sergeant Murphy related that the terrain, not the Germans, was his unit’s greatest initial concern at the bridge. “On the west side of the Merderet River, running about 8,000 yards north and southeasterly at the La Fière bridge area, the Germans had flooded the entire plain by closing the La Barquette locks in 1943. American reconnaissance photo and map experts did not detect the floodwater, for reeds, tall grass, and rushes had grown up out of the immense new marshland. These treacherous waters claimed the lives of many 82nd paratroopers.

“The DZ selection was one of the worst and most tragic mistakes that Allied pre-invasion strategists made,” said Murphy. “Describing this new, wide-open prairie drop, they simply commented: ‘ground here probably soft.’ The Germans couldn’t have conceived a more deadly trap for the paratroopers and glidermen who landed there.”

Murphy continued, “Our sole D-Day mission was to seize La Fière bridge and hold it so that the armor of the 4th Division (coming ashore at Utah Beach) and the 8th Infantry Regiment, plus heavy artillery, could cross it fighting to the west.”

“The Bloodiest Small Unit Struggle in the Experience of American Arms”

As the spearpoint of the 505th, Dolan’s company approached in the predawn blackness. No enemy movement could be seen due to the reduced visibility caused by the foliage, the hedgerows, the high stone walls around the property, and the darkness.

Confusion reigned because Dolan, even after sunrise and at the height of the battle, was unaware for a long time that he was being reinforced by other American units arriving piecemeal on the scene. Moving toward La Fière in A Company’s wake were Colonel Ekman and elements of his 505th PIR; the 508th’s commander, Colonel Roy Lindquist with portions of his regiment, Captain Floyd Burdette “Ben” Schwartzwalder (who would later be the collegiate football Coach of the Year at Syracuse), commander of G Company, 507th, and 45 others from the mis-dropped 507th.

Unaware of the presence of all these other converging resources, primarily because he had no working radios, Dolan maneuvered his 1st and 3rd Platoons into position around the manor. His account of what happened provides a chilling, firsthand view of a battle that military historian S.L.A. Marshall described as “probably the bloodiest small unit struggle in the experience of American arms.”

Dolan directed Lieutenant George Presnell, leader of 2nd Platoon, to maneuver around the buildings from the north side and approach from the flank, using the hedgerows to conceal their movement. When 2nd Platoon neared, the Germans opened fire.

Dolan said, “I directed [platoon leader] Lieutenant Donald Coxon to send his scouts out. This he did, and he also went out with them. He had plenty of personal courage but he didn’t have the heart to order them out without going with them.”

[text_ad]

It was a fateful—and fatal—move. “A few moments later,” Dolan recalled, “a German machine gun opened up, killing Coxon and one of his scouts, Fergueson. Their fire was returned; and, with Major [James E.] McGinity [the battalion executive officer] and myself leading, a few men holding and returning frontal fire, the platoon flanked to the left. At the same time, I directed Lieutenant Presnell to re-cross the road and attack along the northern side down to the bridge. This was done, and the second platoon didn’t meet with any fire until they arrived at the bridge.

Pinned Down For an Hour

“The third platoon continued its flanking move and cut back in toward the road to the bridge. Because of the fire, we calculated that there was just one machine-gun crew that was in our way. It later turned out that there must have been at least a squad dug in at this point, with at least two of them armed with [MP-40] machine pistols. Prisoners captured later, in addition to the German dead, amounted to about the size of one of our platoons [40 men]. There were no German officers captured.

“We cut back toward the road, traveling in a northerly direction,” Dolan noted. “Major McGinity was leading and I was about three or four paces behind and slightly to the right. There was a high, thick hedgerow to our left, and it was in here that I figured the machine gun was located. When we had traveled about two-thirds of the way up the hedgerow, they opened up on us with rifles and at least two machine pistols. I returned the fire with my Thompson sub-machine gun at a point where I could see leaves in the hedgerow fluttering. Major McGinity was killed instantly.

“As luck would have it, there was a German foxhole to my left which I jumped into and from where I continued to fire. I could only guess where to shoot but I had to, as part of the third platoon was exposed to their fire. Lieutenant [Robert E.] McLaughlin, the assistant platoon leader, was wounded and died later that day. His radio operator was also killed. The platoon by now was under fire from two directions, from the point where I was pinned down, and also from the direction of the bridge.”

One of Dolan’s sergeants began lobbing mortar rounds in, but it was all guesswork and, because of the danger of hitting his own men, the mortars stopped.

“I can’t estimate how long we were pinned down in this fashion,” Dolan said, “but it was at least an hour. I made several attempts to move, but drew their fire. On my last attempt, I drew no fire. They obviously had pulled out.”

The effort to seize the small stone bridge started badly and would get worse.

Bullets Were Dancing Off the Water

Eight hundred yards north of the bridge, Colonel Roy Lindquist, commanding the 508th PIR, could hear the gunfire and urged his men to follow the railroad line south toward the sounds of battle. He was joined by Schwartzwalder’s company and the 45 additional men from the 507th.

Lindquist and his contingent of the 508th arrived at La Fière along with Captain Arthur Stefanich’s C Company, 505th. Colonel William Ekman, the 505th’s commander, was there also, as was Captain Schwartzwalder, G Company, 507th. Only then did Dolan realize that he had reinforcements.

After meeting with Stefanich, Dolan said he knew where the other enemy machine-gun positions were and would take them out; he directed his men to flank the manor on both the north and south sides. A five-man patrol from A Company tried getting close to the buildings with their foot-thick stone walls, but a machine gun chattered, killing four. The Germans even had snipers hidden in trees.

Bud Warnecke of Captain Royal Taylor’s B Company, 508th, said his unit was ordered to attack across the swamp and river: “I took my platoon into the river with just our heads out of the water. The German machine-gun fire we received was long range but, like the movies, the bullets were dancing off the water around us.”

Surviving that ordeal, Warnecke was later preparing to attack enemy positions when he, a sergeant, and Lieutenant Homer Jones, who had taken command of B Company when Captain Taylor was injured on the jump, came under machine-gun fire. “I was hit in the shoulder,” said Warnecke, “and felt as if I was hit with a sledge hammer. I was knocked down and on the way got one through my canteen. Got up somewhat dazed and saw that Lieutenant Jones had been hit through the neck. We called for a medic. Sergeant Fecteau, who was nearby, immediately used two fingers and plugged the holes to stop the bleeding.”

The medic arrived, injected Jones with morphine, patched him up, and called for litter bearers to take him away. Warnecke’s wound was judged to be superficial, but his left shoulder turned “blue and yellow.”

Capturing the Manor

At approximately 9 am, Brig. Gen. James Gavin, who had been dropped northwest of La Fière on the west side of the Merderet, arrived at the manor with about 300 men from the 507th PIR. Major Kellam briefed Gavin on the situation and expressed confidence that, with all the men from his and other units now gathering at the bridge and the manor, they would be able to take control very soon.

Gavin, who had once commanded the 505th, knew the men were top notch and agreed with Kellam’s assessment. Gavin then moved south toward Chef-du-Pont to orchestrate the taking of the bridge there, the other major crossing of the Merderet. An intense firefight broke out at Chef-du-Pont, but the Americans captured the town and bridge. Gavin then returned to La Fière where Red Dog Dolan was preparing to make one more assault against the Germans holed up at the manor.

Colonel Lindquist wanted in on the action and sent a message to Dolan that Schwartzwalder’s company would attack from the south side, the 508th would attack from due east, and Dolan should keep attacking from the north. Not surprisingly, given the confusion of the morning, the message never reached Dolan.

Dolan and his men cautiously approached the manor, and someone fired a bazooka round into one of the first floor windows. All shooting stopped. Robert Murphy said, “The Manor battle now was over as far as we in A Company were concerned; it was only a matter of capturing any Germans who remained trapped inside.

“Then suddenly shooting started in the backyard. Some 10 or 12 Germans started firing out of the second-floor windows of the Leroux homestead. Everyone in the 508 patrol and the 505 and 507 men returned fire. After 10 minutes, one of the Germans waved a white sheet or pillow case surrender flag out the window.”

A paratrooper went forward to accept the surrender—and was shot dead, probably by a German at another window who didn’t know that his comrades had already indicated their desire to give up. Another brief, furious round of firing broke out, and the Germans once again surrendered—this time for good.

The paratroopers found the Leroux family huddled in their basement wine cellar, petrified by the battle that had raged for hours above them. The grounds of the shattered manor were littered with the bodies of dead Germans and Americans.

Defenses Established at the Bridge

At about 1:45 pm, Captain Schwartzwalder, G Company, 507th, ordered one of his platoons to try for the bridge. Two men, Pfcs. Johnnie Ward and James Mattingly, made it across when a German at the far end popped up to take a shot; Mattingly emptied his clip into him, tossed a grenade into a machine-gun nest, and wounded several Germans, whom he took prisoner. An officer later said, “It was the best piece of individual soldiering I’ve ever seen.” Mattingly would later receive the Silver Star.

At about this time, an advance party of paratroopers from Lt. Col. Charles Timmes’s 2nd Battalion, 507th PIR—which had been mis-dropped and was surrounded in an orchard northwest of Sainte-Mère-Église, moving south down the west side of the Merderet—reached the causeway and made sure it was clear. The road to Cauquigny was now open for the taking. Taking it was Schwartzwalder’s company, which marched the kilometer to it and linked up with a 10-man advance party from Timmes’s battalion positioned around the village church.

But Schwartzwalder made a crucial error; he left a small force (eight men and one lieutenant, Lewis Levy) at the church in Cauquigny while he and 80 men set off in search of Timmes’s battalion. The Yanks in Cauquigny were about to be overrun by the enemy.

At approximately 2:30 pm, with the battle for La Fière now over—or so everyone believed—Major Kellam set up a defensive force at the eastern end of the bridge and planted mines along the causeway at the western end in case the Germans counterattacked from that direction. A disabled German truck was pushed onto the bridge to act as a further roadblock, and three 57mm antitank guns that had been brought in by glider arrived at the manor. The American position at La Fière was beginning to look impregnable.

The German Counterattack

Then, at around 4 pm intense firing was heard to the west of the bridge, and Lieutenant Dolan spotted a group of paratroopers––a patrol from the 508th that had gone out earlier––rushing back across the marshland. It was obvious that they were being pursued. German forces led by three light tanks of French manufacture were coming down the causeway from the direction of Cauquigny; Levy’s small force that Schwartzwalder had left there had been routed.

Sergeant Elmo Bell, C Company, 505th said, “There were about 12 or 15 [U.S.] paratroopers marching ahead of the tanks.” The tank commander was forcing the paratroopers to pick up mines from the road and throw them into the fields.

With the captured paratroopers being used as human shields, the German force drew nearer to the bridge and manor; none of Dolan’s men dared fire for fear of hitting their fellow soldiers. The tanks then began blasting the American positions with their main guns and machine guns.

Dolan said, “When the lead tank was about 40 or 50 yards from the bridge, the two Company A bazooka teams got up just like clockwork to the edge of the road. They were under the heaviest small-arms fire from the other side of the causeway, and from the cannon and machine-gun fire from the tanks.”

One of the bazooka teams, Privates Lenold Peterson and his loader Marcus Heim, took aim at the lead tank. Before they could fire, though, a burst of American machine-gun fire killed the tank commander who was standing up, exposed, in the turret. Peterson then launched his rocket at the same time one of the 57mm guns fired.

The gun blew the track off the tank, bringing it to a halt. The turret swung around, fired, and killed the gun crew. Meanwhile, the dozen or so captured paratroopers threw themselves to the ground to avoid being hit in the crossfire.

Bazooka man Heim said, “The first tank was hit and started to turn sideways, at the same time swinging its turret around and firing at us. We had just moved forward around a cement telephone pole when a German round hit it, and we had to jump out of the way to avoid being hit as it was falling…. We kept firing at the first tank until it was put out of action and on fire.” Another trooper jumped onto the tank and dropped a grenade into the open hatch, silencing it forever.

“Major Kellam’s Bridge”

It was an astonishing scene. More tanks were pouring machine-gun fire into the American positions, and their main guns were pumping shell after shell at Dolan’s men, who were firing back just as furiously. As the gunners were killed, more paratroopers rushed up to take their places; Sergeant Elmo Bell recalled that at least seven paratroopers died manning one of the guns. Germans, taking cover behind the tanks, were firing rifles and automatic weapons at the paratroopers; mortar rounds were exploding everywhere.

The rest of the American 57mm guns were brought to bear on the two enemy tanks and the infantry around them. Peterson and Heim saw the second tank trying to push the disabled first tank out of the way, so they moved forward and repeatedly blasted the second tank until it burst into flames.

Running low on ammo, Heim dashed through a hailstorm of flying bullets to the other bazooka crew’s position, but they were nowhere to be found. The damaged weapon was lying on the ground, as were a number of rounds. Scooping them up, Heim dashed back to Peterson and put them to good use in knocking out the third tank. With some understatement, Heim said, “This was one of the toughest days of my life. Why we were not injured or killed only the good Lord knows.”

At the La Fière bridge, the German infantry, their tank support gone, broke off their attack and began pulling back toward Cauquigny. Heim and Peterson yelled for more bazooka rounds, and Major Kellam, along with Captain Dale A. Roysdon, the battalion S-3, ran forward with a bag of rockets. At that moment German mortar rounds began exploding on and around the bridge; Major Kellam was killed and Roysdon mortally wounded. Since that day, the little stone bridge at La Fière manor has been called “Major Kellam’s Bridge.”

Cobbling Together Reinforcements

Lieutenant Colonel Mark Alexander, the 505th’s executive officer, was at the regimental command post southwest of Sainte-Mère-Église receiving sketchy battlefield reports from what few operational radios there were. Colonel Ekman was gone, off to control the action around Sainte-Mère-Église. The Germans were trying to recapture the town, and Ekman had ordered Lt. Col. Benjamin Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion, 505th PIR, to move into it, augment Lt. Col. Edward “Cannonball” Krause’s men (3rd Battalion, 505th PIR), and hold it.

A messenger rushed into Alexander’s command post to give him the obsolete news that Major Kellam was reporting that the La Fière bridge was in American hands but enemy tanks were moving in to take it back. Shortly thereafter, another runner arrived with the devastating news that Kellam, McGinity, and Roysdon had all been killed; the situation at La Fière had turned critical. Alexander decided that he needed to get there, fast. He took off in a jeep with his orderly, Corporal Chick Eitelman.

En route they were shot at by the enemy, and Eitelman was wounded in the knee. Alexander dropped him off at an aid station and resumed his run to La Fière. “On the way,” Alexander said, “I found a mixed group of 40 or so 101st and 508th men lying in a ditch along the road. Supposedly someone held them as a reserve. I did not know who, so I rounded them up and took them with me. We arrived at the railroad crossing above the bridge at about 1:30 in the afternoon.” The enemy was still lobbing mortar and artillery fire into the area.

Alexander met with Dolan, who filled him in on the situation. Although A Company had taken quite a few casualties, Dolan still held a strong position. But with ammunition running low, how long he could hold it was anybody’s guess. Just then, General Gavin, who had gone down to Chef-du-Pont to gather reinforcements and bring them back to La Fière, returned. Alexander said, “[Gavin] had 507th men following some distance behind because he heard our men at La Fière were having a bad time. I assured him that the men were in good position and had weathered the attack. He instructed me to take command of the position.

“I said, ‘Do you want me on this side, the other side, or both sides of the river?’

“He thought for a minute and said, ‘You better stay on this side because it looks like the Germans are getting pretty strong over there.’ He was worried that if we attacked them and things went badly, we might lose the bridge altogether. He added that I should hold fast, not allowing passage to the Germans.”

When Lt. Col. Arthur Maloney arrived with about 75 men of the 507th from Chef-du-Pont, Gavin attached them to Alexander’s force, then gathered the men from the 508th and the 101st strays Alexander had brought with him and took them to Chef-du-Pont.

Alexander, trying to think like an attacker, then tweaked Dolan’s defensive positions and beefed up a few of the weak points. He also helped to move a wounded man when the Germans began saturating the area with a mortar and artillery barrage that lasted nearly half an hour.

Later that afternoon, Gavin returned, picked up some more men, and took them back to bolster the river crossing at Chef-du-Pont. Alexander noted, “The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 505 were still having a rough go as well [at Sainte-Mère-Église]. Lt. Col. Krause was temporarily in the aid station after receiving several wounds. B Company was taken from us and attached to the 3rd Battalion in Sainte-Mère-Église. I objected to that when it happened, but Sainte-Mère-Église was being attacked from two sides and they had ongoing fighting while we were being shelled. No Germans were coming across the causeway right then.”

“Doonybrook”

At Sainte-Mère-Église, the best word to describe what was happening in the 82nd’s sector in and around the town is “donnybrook”—an Irish term meaning an “uproarious brawl.” It seemed that on June 6, and again the next day, in every town, hamlet, and field, the American paratroopers were standing toe to toe with the Germans and slugging it out with everything they had—knives, pistols, rifles, grenades, machine guns, mortars, artillery, and tanks—battling without pause, each side knowing the terrible consequences if they lost. It was war without pity and combat without quarter.

And the La Fière bridge, too, was far from being secure. The Germans knew its importance and were about to do everything in their power to get it back.

Two days after the battle for the La Fière bridge began, it was still going strong, with neither side showing any inclination of giving up this important crossing over the Merderet.

When Colonel Harry Lewis’s 325th Glider Infantry Regiment arrived in Normandy, Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, the 82nd’s commander, ordered it to force a crossing in the flooded area to the north of La Fière and attack the Germans to the west of the bridge from the rear. At dark, Lewis sent Major Teddy Sanford’s 1st Battalion into the area, where it was to make a flanking maneuver through the marsh about 850 yards north of the bridge. Company C would take the lead, followed by A and B Companies.

A Medal of Honor For Charles DeGlopper

The glider troops, virgins to combat, were determined to do well but, while fording the marsh shortly after midnight on June 8-9, B and C Companies lost contact with one another. Company C proceeded over a slight rise through a wheat field, entered an orchard, and reached a sunken road. In the dark, wild, intermittent firing broke out and much of the company was decimated.

One man stood tall—literally. Pfc. Charles DeGlopper from Grand Island, New York, was a very big man. Six foot six and over 200 pounds, he towered over everyone else in C Company. While his size made him appear more formidable than the mild-mannered 22-year-old he actually was, it also made him an inviting target on the battlefield. DeGlopper was advancing with the forward platoon when it came under enemy fire.

The platoon leader, Lieutenant Bruester Johnston, was killed. Knowing that his platoon was on the verge of being slaughtered, DeGlopper yelled for his buddies to take off for a hedgerow in the rear while he kept the Germans at bay with his Browning Automatic Rifle. Standing on a roadway in full view of the Germans and drawing their fire to him instead of his buddies, DeGlopper sprayed the enemy despite being hit several times.

DeGlopper remained firing until his wounds brought him to his knees. Even then he did not quit and continued firing until he ran out of ammunition and fell mortally wounded. Afterward, members of his company found the ground strewn with dead Germans and many machine guns and automatic weapons that he had knocked out of action.

The only thing more surprising than DeGlopper’s sacrificial heroism is that, considering the innumerable acts of courage that took place in Normandy, he was one of only two members of an airborne or glider unit to receive the Medal of Honor for extraordinarily heroic actions performed during Operation Overlord.

The Reluctant Charles Carrell

At La Fière, the Germans were of no mind to abandon their attempt to take back the bridge and continued pouring resources into the area; so did the Americans. Because the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR) had only two battalions instead of the customary three that most infantry regiments had, Lt. Col. Charles Carrell’s 2nd Battalion, 401st GIR had been attached to the 325th as its third battalion. Lewis’s 1st Battalion was across the river battling Germans north of Cauquigny.

To break the stalemate at the bridge, Gavin told Lewis at mid-morning on June 9 to employ Carrell’s battalion along with a dozen Shermans from the 746th Tank Battalion and 155mm guns from the 90th Division Artillery and make one final push to secure the bridge. As waiting would serve no purpose, he told Lewis to get the attack started immediately; Lewis in turn, although believing it was suicidal to charge a mass of men through such a narrow, strongly guarded space as the bridge and causeway, gave Carrell the order to carry out the attack.

Carrell, feeling that his battalion had been unfairly singled out as sacrificial lambs, reluctantly gathered his company commanders and outlined what they were expected to do; Captain John Sauls’s G Company, 401st, would lead the attack, followed by Captain Charles Murphy’s E Company. Captain James Harney’s F Company, 401st, would cross last. Once across, Saul’s company would turn left, E Company would turn right, and Harney’s men would dash straight ahead toward Cauquigny—a distance of over 500 yards—and le Motey, just beyond. Everyone agreed that the charge was suicidal, but an order was an order.

One aspect of combat that people who have never been to war fail to appreciate is the tremendous amount of noise made by modern munitions. The sound is truly terrifying––a literal assault on the eardrums as well as the other senses. When one is close to unceasing, shattering blasts, booming explosions, the cringe-inducing rattle of machine-gun and rifle fire, the popping and whizzing of bullets and shrapnel, and the concussions that batter the chest and in themselves can cause death by bursting the heart and lungs—not to mention the fear produced by flying, whirling projectiles of all sizes and the sight of men being violently torn apart—the very act of standing up and charging into such a maelstrom is an act of courage beyond the ken of anyone who has not experienced it.

So, with shells bursting and bullets cutting the air over the small bridge and the unbelievable din of battle physically hammering the very roots of their being, it was not surprising that Carrell’s men naturally hesitated to expose themselves to the fire of both friend and foe. Gavin personally ordered Carrell to get the attack going, but he had been slightly injured in the glider landing and said he did not feel up to the challenge.

When Gavin again ordered him to move out, Carrell lost his nerve and declined, claiming that he was sick. Relieving Carrell on the spot, Lewis turned to Major Arthur Gardner, the 325th’s S-2 (Intelligence) officer, and appointed him battalion commander.

Gavin was not happy about the sacking of Carroll, a fellow West Pointer. “Carroll had never been in combat, never been in a position like that,” he wrote. “But I had to do it. The whole battle was hanging by a thread.”

“Follow Me!”

To bolster the attack, two tank platoons—a dozen Shermans—from the recently arrived 746th Tank Battalion added to the Americans’ supporting fire, and a battery of the 90th’s 155mm guns that had just been brought forward slammed their huge shells into the enemy’s positions, then laid down a smoke screen. But smoke does not stop bullets or shells, and the Germans continued firing blindly through the fog at the bridge and manor.

Gathering his courage at the sight of the landscape to his front being obliterated by the barrage, Captain Sauls yelled, “Follow me!” and led his men from the safety of a stone wall at the manor into the firestorm; many were cut down as they began their charge; soon the bridge and causeway beyond were littered with dead and dying Americans.

Gavin noted, “I was quite apprehensive about the ability of the 325th [i.e., 401st] to make the crossing, since they, too, had not been in battle before.” To stiffen the glidermen’s resolve, Gavin told Captain Robert Rae, commander of Service Company, 507th PIR, to provide every bit of support possible to the troops when they charged the bridge. “I told him also that I was a little afraid that the 325th might break in the fury of the battle. I said that if they did and any of them started drifting back across the causeway, I would signal to him and he was to lead the paratroopers in a charge across the causeway into the German positions. I figured that the momentum of this action would take the 325th along with it.”

At 10 am, every American near La Fière bridge opened up—riflemen, machine gunners, tankers, artillerymen—shocking the Germans with the violence of the massed fire that looked like everything in the American arsenal was being unleashed upon them.

When he was sure that the enemy was reeling from the force of the overwhelming assault, Gavin signaled the glidermen to begin their charge. With great apprehension, normal for troops going into their first battle, the 325th, 401st cautiously started moving forward.

Lieutenant Lee Travelstead, a machine-gun platoon leader, recalled feeling that the order to charge all the way to Cauquigny was “a Kamikaze charge if there ever was one,” in which his men, being slowed down by heavy weapons and ammunition, “would be a bull’s eye kind of target.” But orders were orders and Travelstead and his men followed the 325th, 401st GIR riflemen. “We moved through the fire like a mule pack train,” he said.

The Causeway: “A Log-Jam of Dead and Dying Soldiers”

Some minutes later, unable to see through all the smoke and dust and debris, and worried that the 325th, 401st’s attack had stalled, Gavin alerted Captain Rae and his 90 paratroopers to move onto the bridge. Rae remembered, “As the 325th’s attack got underway, the causeway became a mass of stagnant humanity. It became obvious more men were needed on the west bank to secure a viable bridgehead. At the time the 325th’s attack wasn’t moving forward, so General Gavin came over to me and said, ‘Rae, you’ve got to go and keep going!’

“We came out shouting, forcing our way through the log-jam of dead and dying soldiers and some soldiers refusing to continue the attack. We continued running until we reached the west bank. After we knocked out the German positions on the other side, I split my force, sending half down a dirt road to the south where the 325th was having trouble.” Rae’s force was followed by the Sherman tanks.

Unknown to Gavin, the glidermen’s assault was moving. Sauls, miraculously untouched by enemy fire, had reached the western end of the causeway, blasting Germans with his Tommy gun as he went. One of his platoon leaders, Lieutenant Donald Wason, wasn’t so lucky; he was killed while taking out a machine-gun nest at Cauquigny.

Gavin suddenly felt the need to be where the action was, and both he and Ridgway crossed the bridge during the battle. Gavin noted later, “When I had gone across, I knew I had not realized the extent of the German strength on the far side. In a field a hundred yards from the bridge were a dozen mortars dug in in huge square holes in the earth. There was a great deal of artillery, half-tracks, self-propelled guns. Much of their artillery was horse-drawn, and horses killed and wounded were still in harness.”

Lieutenant Travelstead said, “Dead and wounded were everywhere as I moved steadily along. Then I saw General Ridgway in the causeway trying to remove a cable from the track of a tank to clear the way. It was bad enough for any of us to be there, but a two-star general?”

The battle went on without pause. Travelstead saw the men around him being killed but Ridgway “kept working at the tank, apparently oblivious to all else.” Gavin soon appeared on the scene. “What was going on?” Travelstead asked himself. “It seemed like chaos in front, and here, almost by my side, were both General Ridgway and General Gavin, division commander and assistant division commander of some 10,000 troops, down here on that murderous causeway. Was it so important? Where were all the other troops?”

Side by side the paratroops and glidermen pushed the Germans back. At one point Travelstead was standing in the center of the causeway when two paratroopers suddenly appeared at his side. An instant later an explosion blew the trio into the ditch. Both paratroopers had shielded Travelstead from the blast and were now dead; the lieutenant was wounded but alive. Making his way back to the aid station, he “could not, and cannot, forget the two paratroopers who in a matter of a second, almost as angels, had stepped to my side, taken the explosion and shrapnel from me, and died instantly. Why?” He would wonder forever.

Officers in the Causeway

Now it was the turn of Captain Charles Murphy’s E Company, 401st GIR. Men hunched their shoulders, lowered their heads, said a last prayer, and lurched forward, zig-zagging across the bridge and leaping over bodies strewn everywhere. Bullets thwacked into running soldiers, spinning them to the ground; 35 would die that day on the bridge and causeway. Murphy went down, wounded in the face. Somehow, Lieutenant Richard B. Johnson, leading an E Company platoon, continued into a barrage but was hit in the ankle and arm.

Undeterred, Johnson crawled forward and reached Cauquigny. One of his men kicked in the door to one of the six houses in the hamlet and was killed by fire from Germans inside; a grenade silenced the enemy. Johnson’s platoon sergeant, Henry Howell, was wounded in the arm, and Johnson did his best to patch it up and give him a shot of morphine. “Blood was flowing more than I could account for,” Johnson said, puzzled, “until I realized that a lot of it was mine, coming from that shrapnel slice in my left arm.”

Johnson’s men captured 30 Germans, then 12 more at Le Motey; Sherman tanks were on their heels, as were Generals Ridgway and Gavin. One officer, Lt. Col. Frank Norris, commanding the 90th’s 345th Field Artillery Battalion, was astounded: “The most memorable sight that day was Ridgway, Gavin, and [Lt. Col. Arthur] Maloney [the 507th’s executive officer] standing right there where it was the hottest. The point is that every soldier who hit that causeway saw every general officer, and the regimental and battalion commanders, right there. It was truly an inspirational effort.”

Driving Back the Last Counterattack

That evening Gavin was informed that the Germans were again trying to wrest the bridge at La Fière away from the Americans, and so another battle broke out. Gavin threw everyone he had into stopping the German assault on the bridge––cooks, clerks, anybody who could hold a rifle. It took a bit of doing but, when the advance elements of the 90th Infantry Division finally arrived from the beach, the American position at Manoir de La Fière was unassailable.

La Fière-Cauquigny was just one battle in a whole host of others. The names of a score of heretofore unknown French towns and villages would, within a week, go down in glory in American military history: Sainte-Mère-Église, Sainte Marie-du-Mont, Saint-Côme-du-Mont, Saint Martin-de-Varaville, Saint Germain-de-Varaville, Saint Marcouf, Pouppeville, Angoville-au-Plain, Foucarville, Neuville-au-Plain, Beauvais, Picauville, Beuzeville, and so many others. La Fière, Cauquigny, and Chef du Pont would be added to that list.

My uncle, Pvt. Henry Lisek was a member of the 82nd Airborne, 1st Battalion, 505th. Parachute Infantry Division and took place in the landing at Normandy and fought at Stainte- Mere-Eglise. He passed away in 1971 when I was ten years old. This story above has helped me understand what he went through. Is there a way that I can find out , in more detail, what Company or Squad he was in and what they went through after Normandy?

My Uncle, Pvt. Louis DiGirolamo was in 82nd Airborne, 505th, I company. He was in the fighting at St. Mere-Eglise. He would later be KIA in January 1945 in the Ardennes while I company led an assault on the village of Fosse. He was just shy of 21.

I was fortunate enough to speak with veterans who knew him and fought with him.

His brother, Thomas, was in the 11th Airborne and would be killed in March 1945 in the fight for Luzon.

Gregory my name is Ralph Alvarez and I work at the 82d Airborne Division Museum at Ft Bragg, NC. I was doing some research and found your question on your uncle PVT Henry L. Lisek. I have a roster of the 505th and I looked him up. He was assigned to HHC 2-505th PIR. He was awarded his CIB for his action in 25 Mar 1972Normandy. My roster says he died in 25 Mar 1972. That is what the roster has.

Thanks for responding to our reader.

The Great War in history and great loss of life

My grandfather was James Lansing Mattingly. He is mentioned as winning the silver star at La Fiere Bridge. He died in 1987 when I was a sophomore in high school. I knew he was a DDAY veteran but did not know details of his participation in the war. I do not know of any of my family who knew. This was very moving to find the detailed account of his actions.

Nice article, but the picture with the caption “Shortly after the fighting at La Fière concluded, these American soldiers paused for a photographer with the heavily damaged manor house in the background. The bitter fighting at La Fière was a harbinger of combat to come in Normandy.” with the two soldiers is actually a picture from the west side of the Cauquigny Church that was on the west side of the causeway. You can tell by the curvature at the top of the windows. I’ve done a LOT of research for a game and have every picture that’s available so far of that church from that era(there are not many). But otherwise everything else is spot on.

William Fitzgerald. I am setting up a skirmish game for Cauquigny as well for this Sunday, June 6th. Are you pics posted somewhere? or can you share? thanks, Dan

My father fought in this battle. That same day his youngest brother was killed as a member of the Rangers fighting up the cliffs of Normandie. Dad went on to have his feet so badly frost bitten at Bastone that as every winter began tears would drip from his eyes as his feet burned like they were on fire. God bless all these men. Fr. John Bolderson, Jr.

Brilliant explanation of a complex action. Thank you.

Sir:

Great article. One comment: the majority of airborne troops (approximately 60% +, with higher percentages at expanding radii) landed within a mile or so of their planned DZ’s. Considerable research has documented the landings and proven they were not as bad as has been reported for decades. Scattered troops: yes. Utter chaos: no. Lack of reliable communications in that era was a primary cause for delayed coordination; not the locations of troops. If the same “scattered” drops were done today with modern comms, an airborne command team could still fulfill its D-Day objectives. Placing primary blame for the subsequent events on the drops alone and of themselves, is overly simplistic and clearly not accurate.