By Eric Niderost

Just after dawn on the morning of November 20, 1700, two figures stood atop Hermansburg, a small rise that overlooked the fortress town of Narva in the Baltic province of Estonia. One of the men was plainly a high-ranking officer, an older man whose elaborate uniform and curly wig proclaimed his importance. Yet, curiously, he was deferential to his tall companion, a pink-faced teenager who swept the horizon with his telescope.

The youth was King Charles XII of Sweden, about to engage in the first major battle of his career. Charles was about five feet, nine inches tall, but his slender build made him seem even taller. He had an oval face, hawk nose, and thick lips, redeemed by piercing blue eyes that commanded respect. The young king was dressed in a simple blue uniform with brass buttons that marched down the front of his tunic; no sign of royalty, no gold braid or order of chivalry, was evident.

But perhaps the most unusual feature was his closely cropped blond hair, strands of which could be seen poking out from under a simple black tricorne. This was still the age of Louis XIV, where elaborately curled, full-bottomed wigs were not only standard but also almost mandatory. Charles left his wig in Stockholm, vowing never to wear it again.

Indeed, Charles had more on his mind than court fashion. Sweden was being assailed by a coalition of powerful enemies determined to dismantle an empire built over the previous 75 years by piety and blood. The Swedish king already had won his first laurels by knocking Denmark out of the war, but in facing the Russians he confronted his most daunting challenge.

The king lowered his telescope and spoke to the older man beside him, Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskjold. Charles always spoke with laconic brevity—clear, concise, and to the point. Narva was a major Swedish fortress, and it was being besieged by a Russian army of 35,000 to 40,000 men. Charles had no more than about 9,000 hungry and exhausted effectives.

There, spread out below the two men’s feet, was a classic siege operation at the dawn of the 18th century. It was like an engineer’s plan brought to three-dimensional life. The Russian trenches encircled Narva in a sweeping arc that was some four miles in length. But the besieger had also constructed a second line of fortifications, this time facing out, not in, designed to keep any possible relief force at bay.

A cold rain was falling, and darkening clouds and plunging temperatures brought the chilling promise of a snowstorm. How could such a relative handful of Swedes triumph against a well-entrenched enemy four times its size? Looking down at the Russian host, many Swedish officers must have felt a chill that was entirely unrelated to the weather. But to Charles, the dire situation was a tonic that brought excitement, not despair.

The weather was worsening, but Charles took little notice. “We will attack,” the king said to Rehnskjold, leaving the older man to work out a suitable plan to carry out his royal wishes. Nothing less than Sweden’s status as a major European power hung in the balance. If Charles was defeated or destroyed, Sweden faced ruin and even possible foreign invasion. The Battle of Narva was about to begin.

“Mistress of the North”

The coming contest had its roots in the growth of Swedish power in the 17th century. By 1700, Sweden was the “Mistress of the North,” an imperial power whose greatness was both feared and admired. The Baltic was a “Swedish Lake,” since most of the islands and territories that bordered that great sea were controlled by Stockholm.

The Swedish empire included Finland and the provinces of Karelia, Estonia, Ingria, and Livonia. It also had footholds in northern Germany, with the most prominent being western Pomerania and the seaports of Settin, Stralsund, and Wismar. Sweden had a population of about 1.5 million, but it did possess probably the finest army in Europe at the time.

The Swedish infantry, magnificent in their blue uniforms with yellow facings, were armed with the latest flintlock muskets. They also had a relatively new innovation, the socket bayonet, which allowed a musket to be fired when attached, unlike the common plug bayonet that was jammed into the muzzle.

Swedish soldiers were tough and hearty peasants, accustomed to the icy blasts of Scandinavian winters. They shared the king’s pious fatalism. Charles once said in effect that a man should not worry about being killed in battle; you would not die unless God decreed it was your time to die. This rough assurance gave the Swedish soldier unbounded strength and confidence.

Swedish power brought enemies as well as friends. Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, cast covetous eyes on some of Sweden’s Baltic lands. Frederick IV of Denmark, another potential foe, wanted to reclaim some territory his country lost to Sweden earlier in the century.

A “Window to the West”

But Russia was going to be Sweden’s most dangerous enemy, though few believed this in 1700. After a long slumber lasting several centuries, the Russian bear was at last awakening from its self-imposed hibernation. Czar Peter admired the West and was determined to modernize a still largely medieval country. The Western calendar, Western dress, and above all Western technology were introduced to a backward nation, still drowsy from its long semi-isolation.

Peter, a colossus in body (he was six feet, seven inches tall), knew that Russia needed an ice-free port, a “window to the West,” if the country was ever to be accepted as an equal among the great powers of Europe. Such a seaport would be an umbilical cord to a modernizing nation, bringing in nourishing fresh ideas, trade, and technology to a country that was still a developing infant in Western terms.

The Russians were blocked from going south—that is gaining access to the Black Sea and the Mediterranean—by the weakening but still powerful Ottoman Empire. That left the north, but the Baltic coast was controlled by Sweden. The Swedish army was probably the best in Europe at the time, but if the Swedes were simultaneously attacked on several fronts, their military power might well be diluted and ultimately neutralized.

The secret allies began clandestine preparations for war. They were encouraged by the fact that Sweden’s new ruler, the 18-year-old King Charles XII, seemed a stripling youth. They misread their man. He was pious and moral, athletic and highly intelligent. Above all, he was a born soldier, reveling in military hardships and dangers.

Hostilities began when Augustus the Strong invaded Swedish Livonia without a declaration of war. The Danes also were on the march, invading Duke of Holstein-Gottorp Frederick IV’s territory just south of their own country. The duke was a Swedish ally and also a cousin of Charles XII.

The Treaty of Travendal: Taking the Danes Out of the War

Charles took the news calmly, but inwardly he must have been seething with righteous indignation. He called for his council and announced his intentions: “I have resolved,” Charles said, “never to start an unjust war, but also never ending a just war without overcoming my enemy. Augustus has broken his word. Our cause, then, is just and God will help us.”

Denmark would be the first target of Charles’s offensive. The basic plan was to land troops on Zeeland, a Baltic island where Copenhagen is located. The main Danish army was tied up in Holstein-Gottorp, far to the south. If Charles could successfully land in Zeeland, he could take the Danish capital behind Frederick IV’s back. The Danish king would be forced to sue for peace.

On June 16, 1700, the young Swedish king boarded his flagship King Charles at Karlskrona, the main Swedish naval base. Charles was scheduled to rendezvous with an Anglo-Dutch fleet, which was key to any success against the Danes. King William III of England, who was also ruler of the Netherlands, wanted a quick victory to stabilize the region. Only then could he focus on his main foe, Louis XIV of France.

But before the rendezvous could be completed and the two allied fleets joined, the Swedes had to pass through the Kattegat Sound, a treacherous channel some three miles long. Determined to prevent the allies from uniting, the Danish fleet lay close to the sound’s main Baltic entrance. There were also dangerous shoals in the area, and well-placed Danish cannon added to the list of hazards.

There was one possibility, but Swedish Admiral Wachtmeister hesitated to order it. There was a secondary channel that was relatively unguarded, but its treacherous shoals made it a dangerous proposition. One or more of the Swedish warships might run aground, and that would also block further passage like a cork in a bottle.

Charles overruled his admiral’s objections and ordered the Swedish fleet to enter the secondary channel. Three of the largest vessels had to be left behind—they drew too much water—but after some nail-biting moments the rest of the fleet got through.

The combined allied fleet now numbered 60 ships against 40 Danish men-of-war. The Danish fleet withdrew. There was nothing else it could do. On July 23, a Swedish landing force of some 4,000 men established a beachhead on Zeeland. Charles, impetuous as ever, jumped out of his boat before it touched shore, wading waist deep with drawn sword in hand.

More Swedish troops arrived, and in short order Copenhagen was under siege. Trenches and parallels were dug and the city bombarded. Frederick, hurrying back from the south, quickly capitulated. The Treaty of Travendal, signed August 18, 1700, was a complete triumph for Charles and his allies. Denmark was out of the war.

Peter the Great Raises an Army

In the meantime, Peter had declared war on Sweden with the aim of recovering the lost provinces of Ingria and Karelia. As a first step, the czar would try to take Narva, a fortress in Estonia just over the border from Ingria. The actual Russian frontier was only 20 miles away, an easy march for an army of semi-raw recruits.

The Russian army was indeed new, hastily conscripted and trained in only a few months. The Streltsky, the old pre-reform Russian soldiers, had revolted a few years earlier and were ruthlessly exterminated. Only a few demoralized remnants remained. There were only four well-trained, modern regiments in the Russian army, the Guards regiments. The Lefort, Butursky, Preobrazhensky, and Semyonovsky would have to be the foundation on which the rest of the Russian forces would be built.

Moving quickly, Peter ordered that landowners, including monasteries and elements of the Orthodox Church, be taxed by providing serf peasants as recruits. The ranks were soon filled, but it took time to whip—sometimes literally—these illiterate serfs into shape as soldiers. Mastering the drills was one problem, and learning to load and fire muskets like automatons was another.

The Russian officer corps was also relatively new, filled with courtiers more eager than helpful. At this stage his best officers were, with a few exceptions, foreigners with previous military experience. Peter’s cavalry arm was adequate but unseasoned, but his artillery was impressive. Ironically, 300 cannons had been a gift from Charles XII, originally intended to be used against the Turks.

The Russian Line of Contravallation

In mid-September, Prince Trubetskoy, governor of Novgorod, was ordered to march to Narva with an 8,000-man advance guard and invest the city. Field Marshal Fedor Golovin was tapped to command the main army, though, of course, Peter himself would loom large in any military decisions.

Narva was heavily fortified, with stout walls punctuated by bastions that radiated out like a glowing star, each bristling with cannon. The center of the town was typically Baltic German in style and architecture, with tree-lined streets, quaint gabled houses, and Lutheran churches whose steeples spiked the sky. The town nestled securely on the west bank of the Narva River, a meandering stream that was dotted with small islands.

Just across the river and linked to Narva by a bridge was the former Russian fortress of Ivangorod—now a Swedish outwork—a relic of the time when the area was a border frontier. It was plain that Narva was going to be a tough nut to crack.

Luckily, Peter had the services of General Ludwig von Hallert, a Saxon engineer. Hundreds of Russians were put to work digging trenches and creating siege lines. To guard against attack from the rear—Charles might try to relieve the invested fortress—a line of contravallation was also built to protect the besieging Russian army.

The contravallation line stretched for four miles and featured earthworks nine feet high with a trench six feet deep in front. The earthwork mounds were topped by chevaux de frise, logs whose tops had been carved to a point. Around 140 cannons protruded from the earthen ramparts, making an attacker’s task that much more difficult.

“Surely God Will Protect Us”

In the meantime, Charles was mulling over future plans. Augustus the Strong was besieging Riga, and to Charles the Polish king was the most deceitful and wicked of his enemies. Charles longed for the day when he could punish the double-dealing Saxon. But it was fall, and winter comes early to these northern climes. The Swedes would have to cross the Baltic in a season notorious for autumnal gales.

Headstrong as always, Charles gave orders for the army to be transported to Livonia. He hoped to give Augustus a drubbing, but if that were not possible, he was flexible enough to turn north and deal with Peter at Narva. The Swedish fleet set sail on October 1, 1700, the ships packed with troops and supplies of war.

The fleet was about halfway through its journey when it was hit by a raging storm. Warships and transports were scattered, buffeted by high winds and raging, foam-flecked seas. Some managed to anchor off Courland and ride out the storm; others foundered and were lost. The transports were tossed about like a child’s bathtub toys, injuring many cavalry horses. Charles himself was so seasick he could barely function.

On October 6, the battered Swedish fleet reached Pernau on the Bay of Riga. Ships were repaired, and once the storm was over fresh transports brought additional troops and artillery from Sweden. While his army rested and recovered, Charles learned that the siege of Riga had been lifted and that Augustus was in winter quarters. Cheated of his primary prey, Charles now turned his attention to the Russian siege of Narva, some 150 miles away.

Charles set up his headquarters at Wesenburg, drilling his men while he waited for additional troops to join him. Most of his officers thought an attempt to relieve Narva so late in the season was sheer madness. It was a sevenday march to Narva, through desolate country made even worse by a Russian scorched-earth policy. The land itself was full of bogs, and heavy rains were turning it into a sea of mud.

The officers also pointed out that there was but one road to the beleaguered town and that ran through three passes that were easily defended. Rumor also had it that the Russians had 80,000 men at Narva (actually closer to 40,000). That meant the Swedes would be outnumbered eight to one.

Charles listened patiently, as he always did when matters of importance were discussed. When the last officer had his say, the king announced that, in spite of it all, they would march to Narva and engage the Russians as soon as possible. If Narva was taken, the Russians might well sweep on, taking much of Sweden’s Baltic provinces.

“Surely God will protect us,” Charles said,” since our cause is righteous. Besides, with my brave blue boys behind me [a reference to their uniforms], I fear nothing.” All arguments ceased—they would march to Narva as soon as it was practical.

The Swedish Advance on Narva

But even Charles realized winter was fast coming on—he would march with the troops he had and not wait for reinforcements. That meant that the king had somewhere between 9,000 to 10,000 men, horse and foot, at his immediate disposal. The officers were still doubtful, and the rank and file still didn’t know what to make of their teenaged monarch.

The Swedish army left Wesenburg on November 13. The march was a nightmare and even worse than predicted. The road was already muddy, but the tramp of thousands of feet churned it into a glutinous muck. Slate gray clouds unleashed a steady, driving rain, soaking the soldiers to the skin.

When the army halted for the night it faced new ordeals. The temperatures dropped to below freezing, turning the rain into wind-driven sleet and snow. Eschewing the comforts of royalty, Charles stoically camped on the bare ground, without tent or shelter. It was said that freezing snow speckled his face and body as he slept in the open air.

The darkened skies were lighted by the flaming remains of farm cottages put to the torch by the retreating Russians. There was no food to be had and no fodder for the horses. Some Swedes had a few crusts of bread in their knapsacks, but the constant dampness made the bread so heavy with mold it was all but inedible.

But to the Swedes’ great joy and relief the first two passes on the Narva road were completely undefended. The third obstacle, Pyhajoggi Pass, was defended by Russian cavalry, but the czar’s horsemen withdrew after a skirmish.

Field Marshal Rehnskjold’s Plan of Attack

The news that Charles was coming created an uproar in the Russian siege camp at Narva. At about 3 am on the morning of November 20, Peter summoned Charles Eugene, Duc Du Croy, and told him to assume command of the Russian army. Du Croy was technically an observer from Augustus of Poland. Although an experienced soldier, he didn’t speak Russian, nor did he have confidence in the czar’s officers or his common soldiers.

Du Croy tried to politely decline, but it was hard to say no to a czar. He reluctantly assumed command, and Peter and General Fedor Golovin, the nominal Russian commander, departed soon after. The czar was going to use his presence to speed up reinforcements to Narva and to confront Augustus, asking why he lifted the siege of Riga so precipitously. Golovin was the Russian foreign minister, so it made sense, at least on paper, to have the general go with Peter.

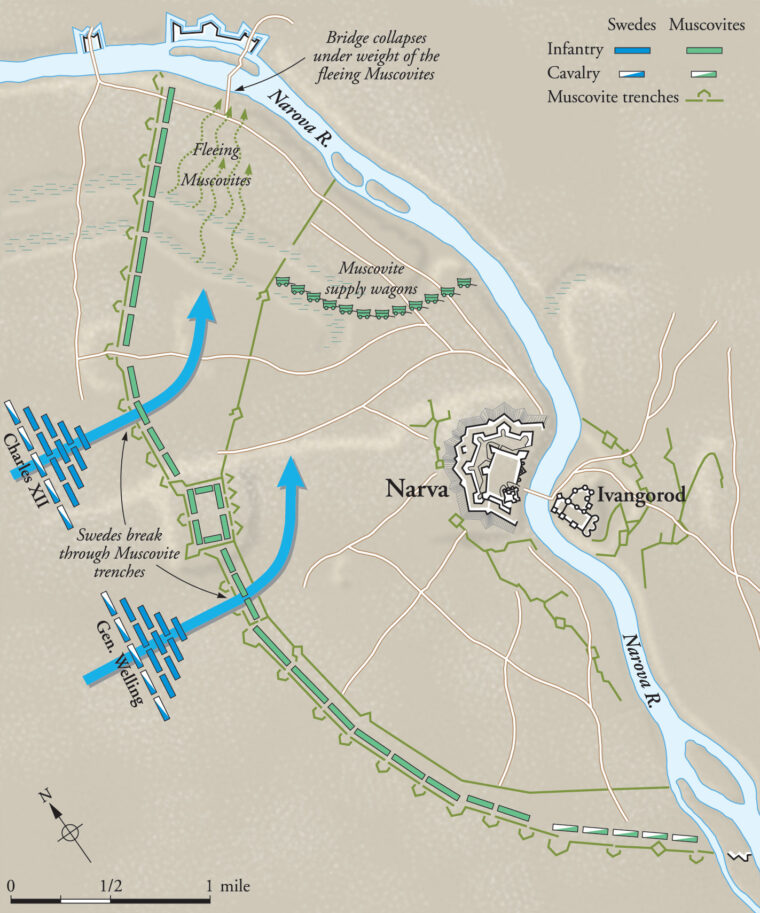

When the Swedish army reached the outskirts of Narva, Charles and Field Marshal Rehnskjold went up to Hermannsburg Hill to scout the enemy positions. Charles noted a weakness—the Russian fortifications were so extensive; the Russian army was spread thin. The Swedish army excelled in the offensive; the catchword “ Ga Pa“ (roughly, “up and at ‘em”) was no mere exhortation, but an article of faith.

If the tough and disciplined Swedish infantry could effect a breach in the Russian works, they could pour in and wreak havoc from within. The bluecoated Swedish “foxes” would be in a very large Russian “henhouse.” It was a bold gamble, but Charles knew it was the best chance of victory. His small army was starving, exhausted, and far from home. Attacking was the only hope of salvation.

The basic plan was devised by Rehnskjold. The Swedish infantry, split into two divisions, would hit the center of the Russian earthworks. Once achieving a breakthrough, the Swedish left under Rehnskjold would push north. The Swedish right under General Otto Vellinck would push south. It was crucial for the Swedes to keep the Russian army separated into two halves. If all went well, they would be able to literally divide and conquer.

The Swedish cavalry would protect the infantry’s flanks and deal with Russian horsemen, if any. They would also be on the lookout for any Russians trying to mount a sortie, or even simply trying to escape. King Charles and his Drabants—Royal Life Guards—would be on the far left with cavalry under Colonel Magnus Stenbock.

“The Snow is at Our Backs”

General Du Croy observed the Swedes’ arrival, and at first felt no cause for alarm. Presumably Charles would start to dig siege trenches—in essence the Russian besiegers would become the besieged. Du Croy, bewigged and dressed in a bright red uniform, was puzzled by what he was seeing. It looked like the Swedes were making fascines, rough bundles of wood bound together, which could be dumped into ditches to help troops cross such barriers.

That could only mean that Charles was about to attack. Du Croy decided to send out a substantial force, which numbered approximately 15,000 men, to confront the newcomers. Unfortunately, the Russians refused to budge from their fortifications. Bowing to the inevitable, Du Croy ordered the Russian troops to place their regimental standards on the earthworks, stand to arms, and await developments.

It was 2 pm when Charles gave the order for the Swedish army to advance. The rain had stopped, but darkening clouds ominously hovered over the combatants. As the Swedes advanced, a ranging snowstorm suddenly descended on the battlefield like the wrath of God. Some Swedish officers hesitated. Should they postpone the attack until the weather cleared?

“No!” shouted Charles, his voice distinctly heard above the howling winds, “The snow is at our backs, but it is full in the enemies’ eyes!” He was right. The snowstorm was a help, not a hindrance, since it blinded the Russians and disguised how few Swedes were advancing against them.

Tough Swedish Discipline

The storm became a full-fledged blizzard, the wind-lashed snow falling so rapidly the horizon was transformed into a blinding white void. The Russian troops, their eyes stung by the pelting flakes, could hear the sounds of the enemy but could see nothing. The blizzard was so perfectly timed it seemed that nature itself was allied with the Swedes.

Suddenly, a line of blue appeared out of the white swirl, apparitions that must have seemed almost like ghosts to the startled Russian soldiers. Most of Peter’s troops were muzhiks, long-suffering peasant serfs, whose bravery and stoicism was matched by an understandable superstition.

It was the Swedish infantry that halted, raised their muskets, and fired a thunderous volley. Flames spouted from hundreds of muskets, and Russians on the earthwork parapet fell like grass. Led by officers waving swords, the bluecoats went forward at the run. The regiments that had fascines threw them into the Russian ditch, making a bridge to cross over. Other Swedes simply dove into the ditch, climbed up, and fought their way into the Russian siege works.

The Russian soldiers fought bravely but were no match for Swedish determination and cold steel. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting ensued. “We slew all who came at us,” a Swedish officer grimly remembered, “and it was a terrible slaughter.” Once a breach had been made in the Russian works the Swedish soldiers poured in like a blue and yellow torrent.

In spite of the pelting snow and growing chaos, Swedish discipline assured that everything went according to plan. The two Swedish divisions separated and went about their assigned tasks with coolness and professionalism. The Russians fought bravely at first, but their morale was weakened by fear, confusion, and sheer lack of experience.

Panic arose and infected the Russian regiments like a deadly contagion. Orderly ranks of soldiers dissolved into fear-stricken mobs, men whose only thought was to escape as quickly as possible. Whole regiments took to their heels, some soldiers leaping over the parapets in an attempt to reach the open fields. Many fugitives were cut down by sword-wielding Swedish cavalry.

A Chaotic Rout: “The Germans Have Betrayed Us!”

Instinctively seeking a scapegoat for their own actions, Russian muzhiks shouted, “The Germans have betrayed us!” “German” was the Russian generic term for foreigner, and for many such officers the feeling was mutual. General Ludwig von Hallert, a Saxon serving the czar, was thoroughly disgusted. “They [the Russians] ran about like a herd of cattle” he recalled. “One regiment was mixed up with another so that hardly 20 men could be got into line.”

General Boris Sheremetev’s cavalry did little to help the situation. The Russian horsemen, many of them dvoriane (nobles), galloped off the field in a wild panic, proving blue bloods could run away just as fast as commoners. Plunging headlong into the river, the fleeing horsemen and their lathered mounts perished in its twisting cataracts.

The Swedes pressed north and south, driving all before them. The Russian retreat soon became a rout. Thousands of terrified Russian soldiers, artillerymen, and wagon drivers desperately tried to cross to the east bank of the Narva River via the Kemperholm Bridge. It was a wild stampede of men, all pushing, shoving, and stumbling over each other in a frantic effort to make good their escape.

The bridge weakened under the unaccustomed weight of horses, wagons, and hundreds of men, and finally its timbers gave way. The whole structure collapsed into the river, taking scores of Russians to their deaths in the cold waters below. Worse still, a major avenue of escape was cut off from the rest of the panicking soldiery.

20,000 Prisoners of War

Charles was in the thick of the fight, but more like a common soldier than a commander in chief. Fearless to the point of recklessness, he exposed himself continuously to danger. At one point the king and his horse fell into a muddy ditch, and the viscous muck held both of them fast. He was freed after much effort but had to leave his horse and one boot behind.

That did not end his adventures. He mounted a second animal only to have the poor beast killed from under him. When a Swedish trooper gave him a third horse, Charles smilingly said, “I see the enemy want me to practice riding.” The king was also hit by a spent musket ball, which was later found in his cravat.

There was one pocket of strong Russian resistance. At the northern end of the battlefield, near the collapsed Kamperholm Bridge, several battalions hastily barricaded themselves behind an improvised wall of supply wagons and cannons. The holdouts included the Preobrazensky and Semyonnovsky regiments under General Ivan Buturlin. These were Peter’s pride, well trained and uniformed in the Western European fashion, and his confidence in them was justified.

A potential defeat loomed on the cusp of victory. Far to the south, General Weide’s 6,000-man Russian division was comparatively unscathed and intact. If Weide decided to mount an offensive, the triumphant but exhausted and still outnumbered Swedes would be caught between him and the Russian holdouts near the Kamperholm Bridge.

Luckily, the Russians capitulated, their spirit finally broken. Charles might well have played the magnanimous victor, but in his heart he was relieved they had surrendered. The king granted generous terms: the officers would be prisoners of war, but the bulk of the beaten army would be released and allowed to return home. In reality, the prospect of guarding some 20,000 prisoners with 9,000 Swedes was too fantastic to even contemplate.

The common Russian soldiers were allowed to keep their muskets, but standards, cannons, and war matériel were to be turned over to the Swedes The booty included 145 cannons, 10,000 cannonballs, 397 barrels of powder, and 230 standards.

A Young King’s Gamble Pays Off

Swedish casualties were amazingly low, with some 667 dead and around 1,200 wounded. It was harder to assess Russian casualties because of the chaotic nature of the fighting. Most accounts agree that the Russians lost 10,000 to 15,000 dead and wounded, and 20,000 were taken prisoner. Few battles have been so one sided.

The Russians were released at dawn the following day. Charles mounted a splendid horse and positioned himself near the repaired Kamperholm Bridge. As the Muscovites trudged past, crossing the span to gain their freedom, they doffed their hats in reluctant homage to their conqueror. Each Russian regiment laid its standard at the feet of the king’s mount, the pile of silken banners growing larger with each passing minute.

Narva established Charles XII as one of the greatest generals of his time. It was the first of many victories he would win in the course of the next decade. But Narva also contained the seeds of defeat and disaster. After a brief interlude of carousing when he was a youth, Charles swore off liquor for the rest of his life. But soon he was drunk with military glory, a far more dangerous intoxication.

The Swedish victory against the odds can be attributed to three factors: Charles’s bold and unconventional leadership, Rehnskjold’s careful planning, and the toughness and professionalism of their infantry. The Swedes were lucky, too, in that they were fighting a new, untested, embryonic Russian army that was still training. Properly led and trained, Russian soldiers were formidable foes, “citadels to be demolished by cannon,” as Napoleon once put it.

After Narva, Charles was faced with two choices: either invade Russia while Peter was still vulnerable or turn around and deal with the duplicitous Augustus of Saxony-Poland. He chose the latter, giving the czar much needed breathing space. Ultimately, when Charles became bogged down in central Europe the pause stretched to eight years.

Over the years some of Charles’s more admirable qualities had hardened. Stubborn courage had become a pig-headed obstinacy; he fought on when he could have had peace on Sweden’s terms. He also had contempt for the fighting qualities of his czarist enemies, not understanding that the Russian army of 1708-1709 was not the Russian army of 1700. The result was a catastrophic defeat at Poltava.

Yet, Narva is rightly remembered as a brilliant victory against the odds, when a young, courageous, and unconventional king gambled and won.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments