By Major General Michael Reynolds

The U.S. 29th Infantry Division was formed in July 1917, three months after America entered World War I. Somewhat surprisingly, it was made up of National Guard units from Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia—surprising since this was a mixture of southern boys and Yankees, and memories of the Civil War, which had ended just over 50 years earlier, were still fresh.

Nevertheless, a circular blue and gray patch worn on the left sleeve of the division uniform symbolized unity in a time of national crisis, and with its new nickname, the Blue and Gray, the division was sent to France in June 1918. It took part in the Meuse-Argonne offensive in October, suffering 5,691 casualties in just 21 days of combat. After returning to the States, the division was demobilized, and the units reverted to their original National Guard status.

Civil War and Revolutionary Legacy in the 29th

Between the world wars, the Delaware and New Jersey units of the 29th were transferred out of the division and replaced by a second Virginia regiment. Thus, the 29th drew its recruits from just two states and the District of Columbia.

The division was composed of three regiments, and the men were indoctrinated from day one in the history of their respective regiments. The men of the 115th learned that its origin lay in the old 1st Maryland and those of the 116th in the 2nd Virginia Regiment dating back to 1760. The latter called themselves the Stonewallers, remembering that at the Battle of First Bull Run the Confederate general, Barnard Bee, seeing Brig. Gen. Thomas Jackson’s brigade standing fast when the battle seemed lost, had shouted to his men: “There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”

The men of the 175th Regiment traced their heritage to the Dandy Fifth of Maryland, named after its handsome full-dress uniform. They were instructed that their forebears had saved George Washington’s army at the Battle of Long Island in 1776 by charging the British lines.

With the exception of the 175th Regiment, which was recruited and based solely in the city of Baltimore, the companies of the 115th and 116th Regiments were decentralized and located in armories across Maryland or Virginia—in towns like Annapolis, Westminster, Salisbury, Winchester, and Charlottesville.

Military service was unpopular in the late 1920s and 1930s, and most National Guard units were understrength and suffered from a lack of training, ammunition, and modern equipment. The 29th Division came together for collective training only two weeks each year. Inevitably, the outbreak of World War II improved recruiting, and on February 3, 1941, the division was inducted into one year of federal service at Fort Meade, Maryland. Two months later the first draft of conscripts, mainly from Maryland and Virginia, arrived and within a short time they outnumbered the volunteers.

Stationed in England

Any ideas that the division might be sent to fight the Japanese following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 were soon dashed, and the demoralizing cycle of humdrum training and guard duties along the East Coast continued relentlessly. Ammunition was still in short supply, and the men wore World War I-vintage steel helmets. Boredom, rather than Japan or Germany, became the biggest enemy, lowering morale greatly.

On March 2, 1942, the 61-year-old commander of the Blue and Gray was replaced, to the delight of the division, by a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute, Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow. An officer of the old school but not a martinet, Gerow was popular with his officers and men. He would go on to command a corps in the European campaign. Ten days later, the 29th was restructured to conform to the triangular organization of Regular Army divisions and reduced in size from 22,000 men to 15,500. It consisted of three regiments (each of three infantry battalions), four artillery battalions, a cavalry reconnaissance troop, and an engineer battalion.

On September 6, 1942, Gerow received orders that his division was to prepare for an immediate deployment overseas, and within a few days the Blue and Gray was moved by train to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. On the 26th, the bulk of the division boarded the giant Cunard liner Queen Mary for an unescorted high-speed crossing of the Atlantic. The balance of the division followed in her sister ship, Queen Elizabeth, and by October 11, the 29th was complete in England. It was to remain there for nearly two years.

The 29th Division spent its first seven months in England in a Victorian barracks in Tidworth in the central-southern part of the country before being dispersed to various towns in Devon and Cornwall in the West Country, towns like Tavistock, Barnstaple, Bodmin, and Okehampton. The soldiers found the winter weather depressing and life unlike anything they had experienced previously. They found the British and their way of life puzzling—no ice or refrigerators, no showers, warm beer, vehicles driving on the wrong side of the road, the perils of English pronunciation, and so on. Keeping warm was a major problem, with no central heating in Army camps and little or none even in the private houses in which some were billeted and others invited.

Some things were familiar and comforting, however—the language, distances measured in miles, even if nobody knew what a city block was, and, of course, girls. And it was hardly surprising that the local girls found the boys of the Blue and Gray attractive—a private first class was paid nearly four times the rate of his British counterpart!

“Twenty-Nine, Let’s Go!”

By the spring of 1943, the 29th was the only U.S. infantry division in the United Kingdom, and the men began to wonder if they would ever see action. Their predecessors in Tidworth, the 1st Infantry Division, had been sent to North Africa, and they were aware that other divisions, including National Guard units, were being sent to that theater directly from the States. Many of the GIs wondered why they were in Europe at all. It was Japan, not Germany, that had attacked their country. The fact that a surprising number of the soldiers were of German lineage certainly did not help matters.

In July 1943, Maj. Gen. Gerow was promoted to command V Corps, and on the 22nd of that month the new divisional commander arrived directly from the States. His reputation had preceded him—a West Pointer and a strict disciplinarian of the old school. General Omar Bradley later described him as “a peppery 48-year-old cavalryman whose enthusiasm sometimes exceeded his judgment as a soldier.” He was Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt.

Despite his reputation, the new commander started with a highly popular move. Sensing that morale was low and that training seven days per week was leading to staleness and boredom, he immediately ordered a three-day rest period and an extension of the previously restricted furlough system. Despite this seemingly generous gesture, Gerhardt soon proved himself a fearsome though competent leader. He was a stickler for neatness and immediately made it clear that nothing but the highest standards were acceptable in his division. Above all, he made strenuous efforts to raise the morale of his men to a point where they considered themselves superior not only to the enemy but to all other troops in the U.S. Army. To this end he invented the battle cry “Twenty-Nine, Let’s Go!” and insisted that his men use it in battle drills, on official correspondence, and even on divisional signposts. It soon caught on.

Gerhardt was determined to infuse a new spirit of aggressiveness into his division and placed great emphasis on hard physical training, weapon handling, and shooting. He even demanded that every man be taught how to swim and insisted that any soldier failing to meet his rigorous training standards be transferred out of the division. This resulted in some infantry companies losing nearly half their original personnel during their time in England.

In late 1943, Brig. Gen. Norman Cota joined the 29th as its new assistant division commander, a post recently introduced into the Army. Cota had been chief of staff of the 1st Infantry Division in the North Africa campaign and was a perfect choice. He inspired confidence and was a natural leader. Fortunately, he and Gerhardt got on famously. The latter, known to the men as Uncle Charlie, was short and neat to the point of being dapper. The former, known as Dutch, was tall and often casually dressed. They made a formidable pair.

Hard Training For Operation Overlord

The nearer D-Day approached, the more intense the training became. In December 1943 and January 1944, the 29th was joined by the 1st Infantry Division, recently returned from action in the Mediterranean, and by tank, artillery, and engineer battalions for landing exercises at Slapton Sands in south Devon. Ships bombarded mock pillboxes, and both the Navy and the assault troops used live ammunition on a lavish scale. The exercise was repeated on April 27, and no one was left in any doubt that they were to be the lead troops in the forthcoming invasion of the European mainland.

Fortunately for the 29th, its landing exercise was carried out successfully and without the calamity that befell the 4th Infantry Division in the early hours of the following day when German E-boats penetrated the escorted convoy of nine U.S. LSTs, sinking two and damaging a third, with the loss of 198 naval personnel and 551 soldiers.

In mid-May, the 29th received a sudden and largely unexpected order to move to special camps between Falmouth and Plymouth. These new camps were isolated, surrounded by barbed wire, and guarded by some 2,000 Counter Intelligence Corps personnel. No unauthorized personnel were permitted to leave or enter, and camouflage discipline was strictly enforced.

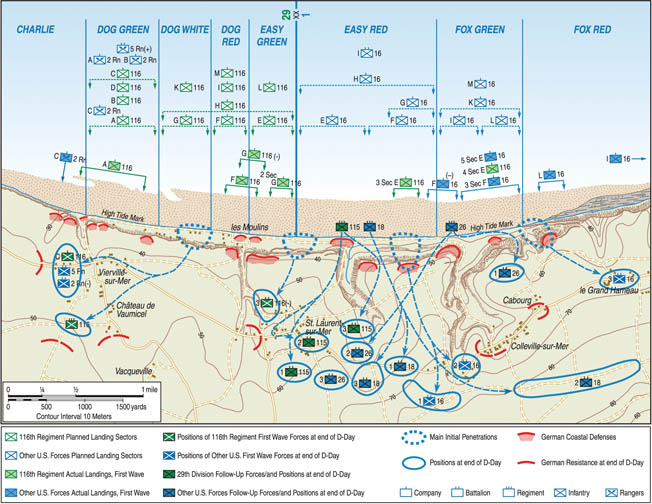

At the time of the move, fewer than 200 members of the division knew any of the details of the invasion plan, and it was to be the last week in May before the GIs were briefed on the greatest amphibious operation in the history of warfare and learned that the Stonewallers (the 116th Regiment) were to spearhead the division’s landing on Omaha Beach alongside the 16th Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division. They were to be the only National Guard unit to land in the first wave on D-Day.

Toward the end of the month the division moved into its final marshaling camps where the men and vehicles were organized into shiploads, and by June 3 they were embarked. However, appalling weather in the English Channel forced General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, to delay D-Day. The men of the Blue and Gray had to spend the next three days in cramped conditions below deck.

Omar Bradley’s Bad Intelligence

H-hour for Omaha was finally set for 6:30 am on June 6, and at 4 am the transports carrying the men of the 116th Infantry Regiment stopped engines 20 kilometers offshore—well out of range of the German shore batteries. The men began clambering over the iron rails in pitch darkness into the landing craft, which hung from the sides of the ships. With an 18-knot wind and heavy swell, this proved a difficult transfer, and a number were injured as they mistimed their jumps. Some even fell overboard to their deaths.

The average man was carrying over 60 pounds of equipment, including an assault jacket instead of his normal pack, combat rations, nine grenades, a half-pound block of TNT, rifle ammunition clips, an entrenching tool, a bayonet, a gas mask, and a poncho, and in some cases extra ammunition belts for BARs (Browning Automatic Rifle), as well as his personal weapon.

The Stonewallers had been told that to ease their passage across the beach the battleships USS Texas and USS Arkansas, steaming within 12,000 meters of the shore, would shortly be opening fire with 14-inch guns and that, in addition, three cruisers and 15 destroyers would drench the enemy defenses with pinpoint, rapid fire. They were also informed that an air bombardment was to blast the Nazi gun emplacements, that British Supermarine Spitfires and four squadrons of American Republic P-47 Thunderbolts would be overhead at all times, and that during the night paratroopers had already landed behind enemy lines to cut off reinforcements. While this may have given them some encouragement, seasickness and the freezing spray from the rough sea were of more immediate concern, and before long, as the landing craft circled in a holding pattern, they were being swamped and the men had to help the crafts’ pumps by bailing with their helmets.

Meanwhile, aboard the cruiser USS Augusta, the commander of First U.S. Army, General Omar Bradley, had just learned that the German 352nd Infantry Division had been moved from St. Lô to the assault beaches for a defense exercise. He quickly forwarded this information to Gerow at V Corps headquarters, but it was impossible to pass it to the troops already aboard their landing craft. Even if Maj. Gen. Gerhardt and officers of the 29th Division had been told about the 352nd, there was nothing they could have done about it. This failure of both the American and British intelligence agencies was particularly serious, for the 352nd was not on an exercise at all—it had taken up its coastal defensive positions 11 weeks before D-Day!

Bradley reminisced later in his autobiography, A Soldier’s Story: “At 0615 smoke thickened the mist on the coastline as heavy bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force rumbled overhead. Not until later did we learn that most of the 13,000 bombs dropped by these heavies had cascaded harmlessly into the hedgerows three miles behind the coast. In bombing through the overcast, air had deliberately delayed the drop to lessen the danger of spillover on craft approaching the shore. The margin of safety had undermined the effectiveness of the heavy air mission.”

And there was more bad news for the Stonewallers. The low cloud, mist, dust, and smoke caused by grass fires set alight on the bluffs by the naval bombardment soon obscured most of their targets and reference points. Most of the shells and rockets fell well short of the sea wall. In fact, few of the German strongpoints were seriously damaged by the air and naval bombardments.

Landing the Shermans

The landing plan for Omaha saw the amphibious Sherman tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion leading the assault. They were due to land at H minus 5 (6:25 am), but the rough seas caused the naval officer in charge of the eight landing craft to give up any idea of launching the tanks 6,000 meters offshore. Knowing they would have little chance of reaching the beach before they were swamped, he decided to run his craft right onto the shore and let the Shermans drive off.

It was a wise decision. The 741st Tank Battalion supporting the 1st Division on the eastern part of Omaha lost 27 of its 32 Shermans in its attempt to swim them. Even so, things did not go as well for the 743rd as hoped. Two of A Company’s tanks were swamped, and B Company, landing opposite the Vierville draw, came under immediate artillery, cannon, and antitank fire and lost seven of its 16 tanks. The company commander’s landing craft was sunk just offshore, and four other officers were killed or wounded, leaving a single lieutenant in command. Nevertheless, the nine remaining Shermans began engaging enemy positions from the water’s edge. Company C touched down successfully to the east but soon attracted fire. The novelist Ernest Hemingway, who accompanied the invasion force but did not go ashore because of an injured leg, wrote later that he saw five tanks hit and set on fire. He described the Shermans as “crouched like big yellow toads along the high water mark.”

65 Percent Casualties in Ten Minutes

Owing to the ineffectiveness of both the naval and air bombardments, many of the infantrymen in the first waves of the 116th Regiment found themselves under direct fire even before leaving their assault craft. The companies landed more or less simultaneously with a company of the 1st Battalion coming ashore just east of the Vierville draw and suffering the worst, losing an estimated 65 percent of its strength within 10 minutes.

One landing craft foundered a kilometer offshore on a sand bar, and most of its complement drowned under the weight of their personal loads; another completely disintegrated after being hit by mortar shells, and in a third all 32 men including the company commander, Captain Taylor Fellers, were killed.

The following account, prepared by the U.S. War Department’s Historical Division after interviewing survivors, paints a horrific picture of what it was like for the hapless soldiers of A Company. “All boats came under criss-cross machine-gun fire…. As the first men jumped, they crumpled and flopped into the water. Then order was lost. It seemed to the men that the only way to get ashore was to dive head first in and swim clear of the fire that was striking the boats. But, as they hit the water, their heavy equipment dragged them down and soon they were struggling to keep afloat. Some were hit in the water and wounded. Some drowned then and there…. But some moved safely through the bullet fire to the sand and then, finding they could not hold there, went back into the water and used it as cover, only their heads sticking out. Those who survived kept moving forward with the tide, sheltering at times behind under-water obstacles and in this way finally made their landings. Within minutes of the ramps being lowered, A Company had become inert, leaderless and almost incapable of action. Every officer and sergeant had been killed or wounded…. It had become a struggle for survival and rescue. The men in the water pushed wounded men ahead of them, and those who had reached the sands crawled back into the water pulling others to land to save them from drowning, in many cases to see the rescued men wounded again or to be hit themselves. Within twenty minutes of striking the beach A Company had ceased to be an assault company and had become a forlorn little rescue party bent on survival and the saving of lives.”

Troubles With the Landings

And so it was to be for many others on D-Day. Company C of the 2nd Rangers, coming in just to the west of the Vierville draw shortly after A Company, lost 35 of 64 men. Company G of the 2nd Battalion, 116th Regiment, which should have landed between the Vierville and les Moulins draws, ended up in scattered groups just to the east of les Moulins. Half the groups gained some protection from the smoke of brush fires set alight by explosions on the bluffs, but those landing farther to the east ran into heavy machine-gun fire, and one boat team lost 14 of its complement of 31.

Company F, 2nd Battalion came ashore just to the east of its planned sector, directly in front of les Moulins; half the company, unprotected by smoke, came under heavy fire and took 45 minutes to cross the exposed beach, many of the men using the beach obstacles for some sort of protection. Half were cut down. The other half of the company managed to reach the protection of the shingle bank, but by then they had lost all their officers and were largely disorganized.

Company E of the same battalion, meant to land on Company F’s left flank, veered over a kilometer to the east and ended up in scattered groups in the 1st Division’s sector. Two of its boats made good landings with only two casualties, but a third was hit by an artillery shell, and the others came under heavy machine-gun fire. The company commander, Captain Lawrence Madill, was killed.

There were two reasons for so many of the assault boats landing well to the east of their designated positions: the strong current running laterally eastward and the difficulties of navigating through the smoke and beach obstacles.

By 7 am, A Company had been cut to pieces at the water’s edge, F Company was disorganized with heavy losses, G Company was scattered but had some groups preparing to move west along the beach to find their assigned objective, and E Company was nowhere to be found in the Blue and Gray sector.

A Special Engineer Task Force, which in the Blue and Gray sector comprised the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion and a number of naval combat demolition units, had the mission of preparing eight 50-meter gaps through the German obstacle belt in just 30 minutes. It ran into trouble even before coming ashore. Delays in loading and navigational problems resulted in four of the assault teams arriving 10 or more minutes late and only three finding their designated disembarkation points. Most were swept to the east, and a number landed where there were no infantry or tanks to give them covering fire.

The conditions under which the teams had to work could not have been worse. Apart from enemy fire, friendly infantry sheltering behind the obstacles due for destruction and others passing through them toward the sea wall caused severe delays. In addition, only six of the Sherman dozer tanks assisting the engineer task force reached the beach in working order, and three of these were soon disabled by artillery fire. Nevertheless, despite appalling casualties, two gaps had been cleared in the 116th’s sector by 7 am. Sadly, the equipment for marking these gaps had been lost, so they were invisible in high water conditions.

The Second Assault Wave

At 7 am, the second assault wave began touching down in a series of landings that lasted 40 minutes. The U.S. War Department’s official narrative has this description: “The later waves did not come in under the conditions planned for their arrival. The tide, flowing into the obstacle belt by 0700, was through it an hour later, rising eight feet in that period; but the obstacles were gapped at only a few places. The enemy fire, which had decimated the first waves, was not neutralized when the larger landings commenced. No advances had been made beyond the shingle, and neither tanks nor the scattered pockets of infantry already ashore were able to give much covering fire…. Mislandings continued to be a disrupting factor, not merely in scattering the infantry units but also in preventing engineers from carrying out special assignments and in separating headquarters elements from their units, thus hindering reorganization.”

The other three companies of the 1st Battalion, 116th Regiment were scheduled to land on a one-kilometer front to the east of the Vierville draw at 7 am in support of its now decimated A Company. Only two or three sections did so. B Company’s assault craft failed to recognize the essential landmarks, and the company ended up scattered a kilometer on each side of the A Company survivors. Those who did land in the right place suffered the same fate as their comrades, and the company commander, Captain Ettore Zappacosta, was killed.

Company C landed 10 minutes later in relatively good shape, but a kilometer to the east of the Vierville draw. Drifting smoke gave it protection from direct fire, and it suffered only five or six casualties but lost all its flamethrowers, 60mm mortars, bangalore torpedoes, and demolition charges when the boat carrying them overturned in the surf. The company found itself on its own but sheltered by a meter-high wooden sea wall.

Company D (Heavy Weapons) was less fortunate. One boat was swamped and had to be abandoned, another was sunk by a mine or artillery round, and a third stopped 100 meters offshore. The company commander, Captain Walter Schilling, was killed—the third in the same battalion that morning—and only three of its six medium mortars, three of its 11 machine guns, and a limited amount of ammunition were brought ashore.

Reaching the Shingle

Major Sidney V. Bingham, Jr., the commander of the 116th’s 2nd Battalion, had been among the first to reach the shingle, but for nearly an hour he had no radio to contact the widely scattered elements of his battalion, and his attempt to organize an assault at les Moulins was unsuccessful. He did manage to get about 50 men across the shingle near a prominent three-story house at the mouth of the draw, and although he personally led a group of 10 men nearly to the top of the bluff east of the draw, they were unable to knock out an enemy machine-gun nest and had to return to the house.

The last company of the 2nd Battalion, the Heavy Weapons Company, had become dispersed during the run-in to the beach, and its machine-gun platoon and two mortar sections ended up in the 1st Division’s sector; the rest of the company, after suffering heavy casualties, found themselves around les Moulins.

At approximately 7:15 am, Lt. Col. Max Schneider’s Ranger force of eight companies approached the Vierville draw in 18 landing craft. Two companies were from the 2nd Rangers and six from the 5th. Three other companies of the 2nd Rangers, under Lt. Col. James Rudder, were at this time assaulting the German strongpoint at Pointe du Hoc, but nothing had been heard from them and it was wrongly assumed that the assault had failed. Schneider soon assessed the situation in front of him and ordered his force to swing east. Even so, A and B Companies of the 2nd Rangers landed where A Company of the 116th had been decimated and suffered the same fate. Only about half reached the sea wall. Fortunately, the 450 men of the 5th Rangers came ashore halfway between the Vierville and les Moulins draws with only five or six casualties.

Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence Meeks’s 3rd Battalion of the 116th should have followed the 2nd Battalion onto the two-kilometer sector of beach astride the les Moulins draw between 7:20 and 7:30. In fact, it came ashore a few minutes late, well to the east, with part of L Company and the whole of M Company in the 1st Division’s zone. Fortunately, there were only a few casualties, and it is clear that the later assault waves had a much easier time than those landing on or just after H-hour.

By 7:30 am, the exhausted men of the 116th Infantry Regiment were lining the whole of the sea wall or shingle embankment in their sector of Omaha Beach. In some areas, notably in front of the German strongpoints guarding draws, losses in officers and NCOs were so high that remnants of units were practically leaderless. Engineers, Navy personnel from wrecked craft, and elements of other supporting units were all mixed in with the infantry. And now there was a problem of morale.

The tide was drowning wounded men who had been cut down on the sands, and bodies were being carried ashore just below the shingle. Stunned and shaken by what they had experienced, the men found the sea wall and shingle bank all too welcome as cover. Ahead of them, with wire and minefields to go through, was the area between the sea wall and the bluff, and this was fully exposed to enemy fire. Beyond that were the bare and steep bluffs.

“Let’s Get the Hell Off This Damned Beach!”

It was into this desperate and seemingly hopeless situation that Cota, the deputy commander of the Blue and Gray, and Colonel Charles Canham, the commander of the 116th, and their command groups disembarked at 7:30. Losing only one officer, they landed more or less halfway between the Vierville and les Moulins draws and found C Company of the 1st Battalion, some 2nd Battalion elements, and 450 men of Max Schneider’s Provisional Ranger Force to their left and right. In most places the men were crowded shoulder to shoulder, sometimes several rows deep.

Realizing that the situation was now critical and that they had little or no chance of storming the enemy strongpoints defending the Vierville and les Moulins draws, Cota and Canham resolved to advance up the bluffs. This involved crossing the flat salt marsh, some 100 meters deep, devoid of cover and blocked by a double-apron wire fence and an antipersonnel minefield. The bluffs themselves were up to 30 meters high, steep and bare but pockmarked with small folds and depressions that provided some cover. Fortunately, the main German defenses were sited to cover the beach and the draws themselves rather than the ground in between.

Cota immediately took personal command of one group of soldiers, and after the first man was cut down as he tried to move through a gap blown in the wire, led the way himself in the dash to the foot of the bluff roughly halfway between the draws. Cota has been credited with the exhortation, “There are two kinds of soldiers on this beach—those who are dead and those who are going to die! So let’s get the hell off this damned beach!” However, those words were actually spoken by Colonel George Taylor of the 16th Regimental Combat Team, 1st Division.

There were countless other acts of bravery by young officers and NCOs as they started breaching the wire obstacles and leading their men off the beach and through the minefields. Company C of the 116th, under Captain Berthier Hawks, who had suffered a crushed foot in the landing, led the way at about 7:50. Then, at 8:10 am, Max Schneider gave the codeword “Tallyho.”

It was the order for each platoon of Rangers to make their own way up the bluff and on to their designated assembly area south of Vierville-sur-Mer. According to the memorial plaque to the Rangers in the Vierville draw, this happened after Cota gave the order, “Rangers, lead the way!” Colonel Canham, despite a severe wrist wound, also led a mixed group of 2nd Battalion men up another part of the bluff nearer to les Moulins at about the same time.

Pushing Past the Bluffs

Once on the hillside, the various groups were protected from direct fire and by the smoke from the grass fires. In some places the smoke was so thick that men put on their gas masks. Cota tried to contact the 1st Division during his move up the bluff to report his own actions and to find out what was happening on the other part of Omaha, but without success.

By 8:30 am, the last of more than 600 men were leaving the sea wall, and a half hour later the crest of the bluff had been secured. No Germans were found in the trenches there, and remarkably few casualties had been incurred. Along with C Company of the 116th, there were men from B, F, G, and H companies, the 121st Engineers, most of the 5th Rangers, and of course Cota and Canham with his Regimental Headquarters. In the case of H Company, a machine-gun platoon had moved laterally all the way from the 1st Division’s part of the beach. But the moves up the bluff had been uncoordinated, with few of the men being aware of what was going on except in their immediate vicinity.

On reaching the top of the bluff, no one could see more than a couple of hundred meters because of the many hedgerows, and most had no idea what to do next. When Cota arrived, he found elements of the 116th and 5th Rangers scattered all over the fields beyond the crest, with the furthermost groups near the coastal road. Some sporadic long-range machine-gun fire was coming from the direction of Vierville, and the occasional artillery round landed in the general area, but there was no organized opposition. Even so, it was another hour before Cota was able to bring some order to the mixed force and get units moving again. He personally organized some of the men into fire and maneuver teams and led the advance across the open fields.

The small number of Germans in the area retreated, and the Americans were soon able to advance along the track connecting les Moulins to Vierville-sur-Mer. Again C Company of the 116th was in the lead, entering Vierville shortly before 11 am. Cota’s group was not far behind. No Germans were found in the village, but a platoon of B Company advancing toward the Chateau Vaumicel, just south of Vierville-sur-Mer, had to overcome a small German resistance nest and then beat off a counterattack. The Germans had deployed from three trucks coming up from the south. Canham’s group of 2nd Battalion men with some Rangers attached had been equally successful in their move from the beach, and they arrived in Vierville-sur-Mer with few casualties.

Taking the Vierville Draw

Just before midday, C Company of the 116th and B Company of the 5th Rangers began a move down the coast road toward Pointe du Hoc. About 500 meters out of Vierville-sur-Mer, however, they were halted by enemy machine guns. A full-scale attack by the main Ranger force to overcome this opposition was planned for the early evening but was later cancelled. The Rangers were now an essential part of the force defending the hard-won gains south and west of Vierville-sur-Mer, and Colonel Canham was not prepared to risk losing them. His force had few heavy weapons and no tanks or supporting artillery. Some guns of the 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion had been landed on the beach, but the crest of the bluff prevented them firing in close support.

At 6:30 pm, John Metcalfe, commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, after finally managing to leave the cliff area to the west of the Vierville draw, reported to Colonel Canham in Vierville-sur-Mer. This was the first time that the regimental commander became aware of the true state of his 1st Battalion, and it would be another five hours before he learned the full facts about his 2nd and 3rd Battalions at the head of the les Moulins draw near St. Laurent-sur-Mer.

By midday Cota and Canham had much of which to be proud, but the main task of clearing the two draws to enable tanks and vehicles to exit the beach was unfinished. At around 1 pm, a heavy naval bombardment, including fire from the battleship Texas, was directed at the strongpoints guarding the Vierville draw, and it was not long before a destroyer reported Germans leaving the concrete emplacements to surrender.

Shortly afterward, Dutch Cota, with his aide and four men, calmly walked down the road to the beach to see why no vehicles were coming up. After receiving some scattered small-arms fire and capturing five Germans, whom they made lead the way through a minefield, the Cota group reached the beach to find the sad remnants of A Company of the 1st Battalion and some Shermans of B Company of the 743rd Tank Battalion farther to the east.

Cota found that despite their heavy casualties, the loss of some 75 percent of their equipment, and isolated enemy snipers, Lt. Col. Robert Ploger’s 121st Engineers were about to start work on the obstacles in the draw. However, there were not enough infantry available for the systematic mopping up of the Germans still in the area, and the engineers themselves had to send out combat patrols to do the job, delaying their proper mission.

Slow Advance on St. Laurent-sur-Mer

Dutch Cota continued his walk along the promenade to see what had happened at les Moulins. He was unaware that shortly before 10 am the commander of V Corps, General Gerow, had ordered Colonel Eugene Slappey’s 115th Regiment of the Blue and Gray to land in support of the beleaguered 116th.

Slappey’s men had been loaded into a dozen large landing craft, each capable of carrying a company and putting them, dry-shod, straight onto the beach. The problem, however, was navigating these slow 246-ton craft through an uncleared obstacle belt in the face of continuing artillery fire. For the men of the 115th there was an additional problem—their vehicles were not due to come ashore on D-Day, and so they were carrying abnormally heavy loads including extra ammunition.

The 115th was ordered to land near the les Moulins draw, but it soon became clear to the captains of the landing craft that in the absence of cleared and marked lanes through the beach obstacles a landing in that sector was out of the question. They asked for new orders and, despite the chaos there, were told to come ashore in the 1st Division’s sector, about 1,500 meters east of les Moulins.

Although the landing was difficult, with several craft colliding, it was achieved with remarkably few casualties. Slappey soon received orders from the deputy commander of the 1st Division to attack and secure St. Laurent-sur-Mer, which was thought to be defended by about a company of Germans. He in turn ordered his 1st Battalion to cut off the village from the rear while the other two battalions attacked it frontally.

The 115th’s advance and attack on St. Laurent-sur-Mer did not go as planned. Although the 1st Division had marked a few lanes through the minefields below the bluffs, the men of the Blue and Gray did not trust them, and progress was painfully slow. Lt. Col. William Warfield’s 2nd Battalion did not start its attack on the village until late afternoon. Even then, naval gunfire fell short, causing a number of casualties in the battalion, and the attack, despite the support of four Shermans of the 741st Tank Battalion from the 1st Division, ground to a halt.

Slappey gave orders for the 2nd Battalion to break off the action and link up with the 1st Battalion. The latter had reached an area south of St. Laurent-sur-Mer near the Formigny road at about 6 pm after running into snipers and mortar fire, which killed its commanding officer, Lt. Col. Richard Blatt. Major James Morris took command. Major Victor Gillespie’s 3rd Battalion still had not reached the St. Laurent-sur-Mer-Colleville-sur-Mer road when darkness fell shortly after 10 pm.

June 6th Ends For the Blue and Gray

On arrival in the les Moulins sector in the mid-afternoon, Dutch Cota found the resistance there still strong enough to block any vehicular movement, and by this time the beach had become heavily congested with vehicles. Elements of the 81st Chemical Battalion, three engineer battalions, naval fire control parties, advance elements of artillery units, medical detachments, antiaircraft units, and even a British RAF group had all started to come ashore before 8 am, making it difficult if not impossible for the Shermans trying to support the infantry. Indeed, half-tracks, jeeps, and trucks all found themselves on a narrowing strip of sand without any exits opened through the impassable shingle embankment. It was one huge traffic jam. Enemy artillery and mortars had easy targets.

Cota also found that although the 3rd Battalion of the 116th, less M Company pinned down on the beach in the 1st Division’s sector, had reached the high ground east of the les Moulins draw, its attempt to move south had been blocked by Germans in and near St. Laurent-sur-Mer. It made less than a kilometer’s progress during the rest of the day, mainly because small enemy machine-gun detachments in well-prepared positions covered the open ground over which it had to advance to its assigned assembly area west of the village. By last light, the bulk of the 3rd Battalion, the command group, and a few remnants of the 2nd Battalion were therefore still at the head of the les Moulins draw. They were unaware of the presence of the units of their sister regiment, the 115th, only a kilometer away to their southeast.

General Gerhardt, commander of the 29th Division, had come ashore during the mid-afternoon and set up his command post in an old quarry in the Vierville draw, but until Dutch Cota met him early that evening he had no real idea of the whereabouts of his two regiments ashore. Cota briefed him as best he could, although even he was not fully aware.

By last light on June 6, C Company of the 116th, the 5th Ranger Battalion, and A, B, and C Companies of the 2nd Ranger Battalion were defending the solid stone buildings on the western edge of Vierville-sur-Mer. Colonel Canham’s regimental command post and elements of the 1st and 2nd Battalions were about one kilometer southwest of the center of the village, and C Company of the 121st Combat Engineer Battalion was holding the Chateau Vaumicel. The 9th Squad, 3rd Engineer Platoon had breached the concrete wall at the bottom of the Vierville draw at 5 pm, and the rest of the company had cleared enough of the remaining obstacles to allow vehicles to move into the village by nightfall. The tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion went into bivouac 100 meters west of the village at about midnight. Sixteen Shermans had been lost, and one was disabled.

In the St. Laurent-sur-Mer area, elements of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 116th were at the head of the les Moulins draw, which was still barred by enemy resistance in the old strongpoints. The 1st Battalion, 115th Regiment was a kilometer south of St. Laurent-sur-Mer by the road to Formigny, the 2nd Battalion a kilometer southeast of the village, and the 3rd Battalion 1,500 meters to the east.

In the case of artillery, all but one of the guns of the 111th Battalion supporting the 116th had been lost, and none of those of the 110th, due to support the 115th, had been landed. The commanding officer of the 111th, Lt. Col. Thornton Mullins, was wounded soon after leading his advance party ashore, and he died a few hours later. Five self-propelled guns of the 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion had been lost in the morning, but the rest of the battalion had come ashore during the afternoon and one battery had moved inland at 6 pm to support the 115th Regiment near St. Laurent-sur-Mer.

1,007 Casualties of the 116th Regiment

The American losses on D-Day were horrendous. The 116th Regiment alone suffered 1,007 casualties: 247 killed, 576 wounded, and 184 missing. Sadly, the peacetime system of recruiting complete companies from specific towns and areas led to some tragic consequences. Bedford, Virginia, a village of only some 3,000 people, lost 23 men on D-Day, with 22 of them, including three sets of brothers, in A Company, 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry.

A number of historians have criticized the American plan for the Omaha landings. They say that the assault craft were launched much too far out to sea and that the initial attacks were directed head-on against the German strongpoints rather than at the more weakly held areas between these strongpoints. While it is certainly true that the longer than strictly necessary run-in to the beach caused difficulties with navigation and led many units to land much farther to the east than planned, the second accusation is quite simply wrong.

No companies were directed head-on at the strongpoints, but Omaha was the most strongly defended beach on the Normandy coast, and the interlocking structure of the German defenses ensured that wherever the Americans landed they would come under both direct and indirect fire. Suggestions that the Americans should not have landed on Omaha at all ignore several basic facts. First, their mission at this stage of the campaign was to clear the Cotentin Peninsula and capture the port of Cherbourg. Second, it was militarily unacceptable to leave a gap of more than 40 kilometers between Utah Beach and the Canadian and British beaches in Normandy. Third, it was the only possible landing site between Utah and those beaches.

In summary, it has to be said that the performance of the majority of the untried and unbloodied American soldiers on Omaha Beach on D-Day was exceptional, and in the case of some of the leaders of the Blue and Gray, notably Dutch Cota, Charles Canham, Sidney Bingham, and Berthier Hawks, outstanding. Many junior officers and NCOs, like Captain Lawrence Madill of E Company, Lieutenants Anderson of L and Hendricks of G, and Sergeant William Norfleet of D Company, to mention but a few, displayed qualities of great leadership and bravery.

It is not surprising that the Stonewallers won 23 Distinguished Service Crosses, 10 Silver Stars, and 100 Bronze Stars on this day. Brig. Gen. Cota, Colonel Canham, and Major Bingham were among those who were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments