By Michael D. Hull

His name was Doris, but he was a powerfully built football fullback, a heavyweight boxer, and the first black American hero of World War II.

He distinguished himself during the Japanese sneak attack against Hawaii on Sunday, December 7, 1941, and gave his life for his country two years later. Poems and songs were written about him, a Navy ship was named in his honor, and he was memorialized at the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor.

The Humble Origins of a Pearl Harbor Hero

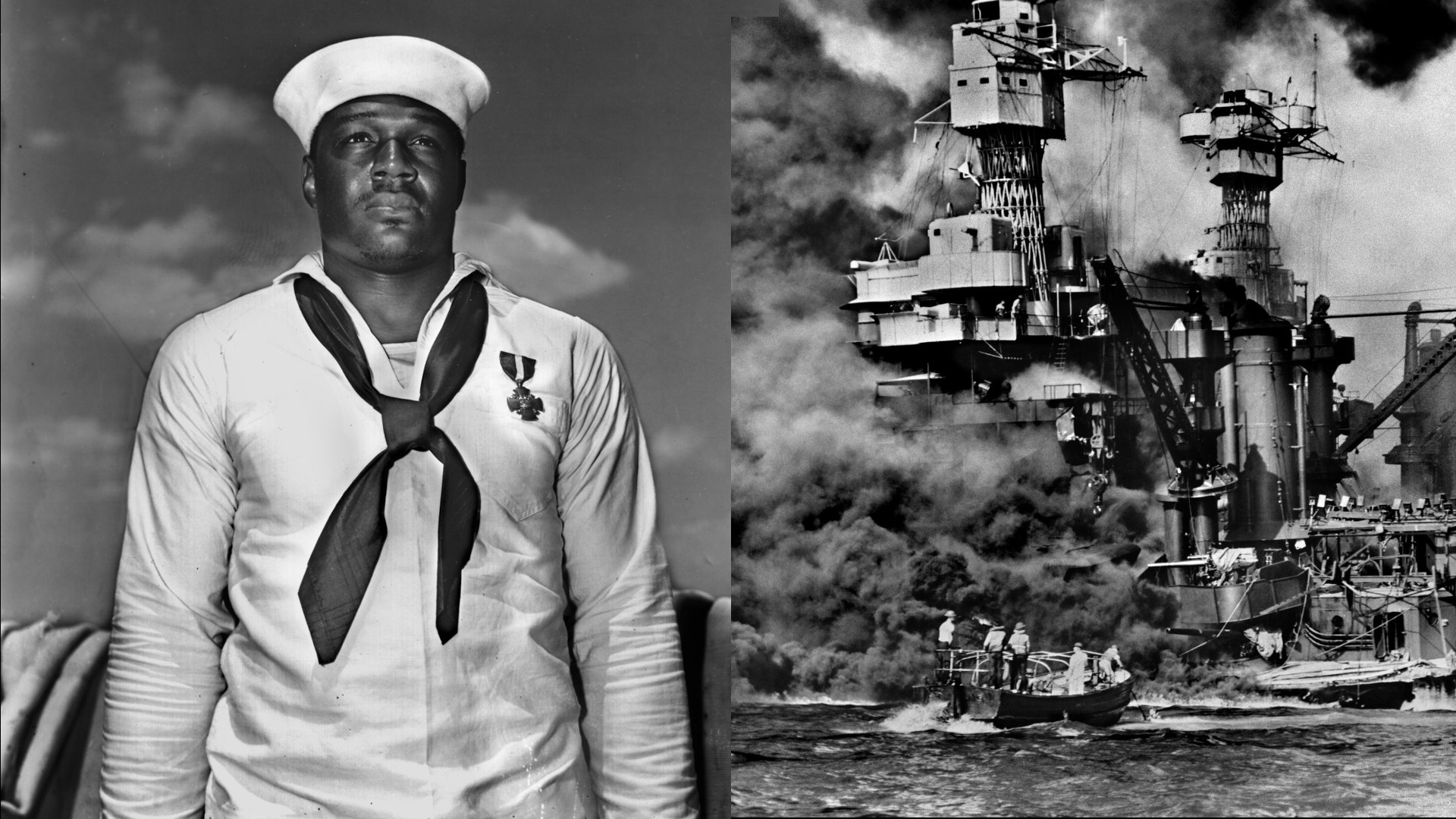

Doris Miller, known as “Dorie” to his shipmates in the U.S. Navy, was a humble seaman from humble origins who became a legend and an inspiration to America’s black community during the war. His extraordinary courage on December 7 brought him the Navy Cross, a commendation by the secretary of the Navy, and praise from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet.

Dorie Miller was born on October 12, 1919, to Conery and Henrietta Miller of Waco, Texas. He had three brothers, one of whom would serve in the Army during World War II. Dorie attended Waco’s Moore High School, where he distinguished himself as a battering ram fullback on the football team. When not in school, the barrel-chested young athlete worked on his sharecropper father’s farm.

At the age of 19, Dorie decided that he wanted to travel and also earn money to help support his family, so he went to Dallas and enlisted in the Navy as a mess attendant, third class, on September 16, 1939, two weeks after the outbreak of World War II. After undergoing basic training at the Norfolk, Virginia, Naval Station, he was assigned briefly to the USS Pyro, an ammunition ship.

On January 2, 1940, Miller was transferred to the Colorado-class battleship USS West Virginia (BB-48). Commissioned on December 1, 1923, the 32,000-ton battleship mounted eight 16-inch guns and was regarded as one of the best vessels in the U.S. Fleet. Miller found his athletic prowess in demand aboard the “Big Weevie,” which had long emphasized sports activities for morale building among her crew, winning the Iron Man athletic trophy more than any other ship. The young Texan became the ship’s heavyweight boxing champion. He was assigned in July 1940 to temporary duty aboard the battleship USS Nevada and at the Secondary Battery Gunnery School and returned to the West Virginia on August 3.

“The Japs are Attacking Us!”

Early on the balmy morning of December 7, 1941, the battleships, cruisers, destroyers, minesweepers, submarines, and tenders of the U.S. Pacific Fleet lay at anchor, peaceful and unsuspecting, around Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. On Battleship Row, the West Virginia was anchored next to the USS Tennessee and astern of the USS Maryland and USS Oklahoma. Sailors stirred from their bunks that morning, headed to the messes for breakfast, and readied themselves for morning colors and Sunday church services.

Aboard the West Virginia, mess attendant Dorie Miller was below deck collecting laundry and starting another routine day of menial tasks that were the prescribed functions of black sailors in the segregated U.S. Navy. At 7:55 am, his chores were abruptly interrupted by the sounds of explosions, guns firing, and seamen shouting, “The Japs are attacking us!”

Without warning and against almost no opposition, the first of two waves of 360 Japanese carrier-borne torpedo bombers, dive bombers, and fighters had burst through the overcast and swept in over the island of Oahu to attack the ships, airfields, and other U.S. military installations. Two years and three months after its outbreak, America had been suddenly and brutally thrust into the global war.

Led by Kate torpedo bombers, almost 200 planes in the first enemy attack wave flew in low and fast over Pearl Harbor, loosing their projectiles on Battleship Row. Three battleships—California, Oklahoma, and West Virginia—were struck. The second run hit a cruiser and capsized a minelayer, and the third struck another cruiser and the old battleship USS Utah. Under eight simultaneous dive bomber assaults, four more battleships—Nevada, Maryland, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania—caught fire, while the venerable battlewagon USS Arizona took hits in her forward magazine and boilers. She blew up with the loss of 1,103 officers and men. Within minutes, Pearl Harbor was an inferno of explosions, fires, and high columns of billowing black smoke.

Meanwhile, Japanese planes bombed and strafed the Ford Island and Kaneohe Naval Air Stations, the Marine Corps air base at Ewa, and the Army Air Forces’ Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows Fields, where bombers and fighters were parked wing-to-wing and almost completely wiped out.

Captain Bennion’s Posthumous Medal of Honor

Aboard the West Virginia, messman Miller and other sailors scrambled topside to assist on deck when they felt the ship convulse and heard the din of sudden war overhead. The Big Weevie was burning and severely damaged after taking hits from two 1,000-pound bombs and six or seven torpedoes. She listed rapidly, but this was corrected by prompt counterflooding, allowing the battlewagon to settle almost upright on the harbor bottom. Her blackened, battered superstructure remained above water.

On deck, Miller was knocked down by the force of another explosion, but he recovered and assisted fire and rescue parties that had been organized by the ship’s well-trained crew. Because of his considerable physical strength, Miller was able to carry several wounded men to safety. Despite frequent enemy dive bombing and strafing, all hands fought the fires. “Their spirit was marvelous,” reported the ship’s surviving executive officer. “Words fail in attempting to describe the magnificent display of courage, discipline, and devotion to duty of all.”

On the West Virginia’s exposed battle conning tower, her skipper, Captain Mervyn S. Bennion, doubled up. Steel fragments, probably from an armor-piercing bomb that had just struck the nearby USS Tennessee, had torn into his stomach. Lt. Cmdr. T.T. Beattie, the ship’s navigator, loosened Bennion’s collar and summoned a pharmacist’s mate. Under continued strafing and as fires swept toward the bridge, Dorie Miller joined Lieutenant D.C. Johnson, the ship’s communications officer, in dragging the almost disemboweled Captain Bennion to cover and attempting to move him from the bridge.

But the skipper, knowing that he was dying, maintained command and was concerned only for his ship and crew. Lying on the deck of his bridge, he ordered that he be left alone, and his life flickered out a few minutes later. Along with Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, killed aboard his flagship, the Arizona, Captain Bennion was later awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Vice Admiral Walter S. Anderson, himself a prewar skipper of the West Virginia, said later, “He was a bona fide hero. I did not personally know enough to recommend him for the Medal of Honor, but I am glad he got it, because that captain of the West Virginia merited it if anybody ever did.” Bennion was one of 105 men killed out of the battleship’s complement of 1,500.

“I Just Grabbed Hold of the Gun and Fired”

After the attempt to assist his dying skipper, mess attendant Miller joined Lieutenant F.H. White on the ship’s forward guns. Without hesitation, he positioned himself behind a big .50-caliber antiaircraft machine gun. He had never been instructed how to fire a gun, but Miller quickly figured out how the weapon worked and began firing at strafing Japanese planes. “I just grabbed hold of the gun and fired,” he reported later. “It wasn’t hard. I just pulled the trigger, and she worked fine. I had watched the others with these guns…. Those Jap planes were diving pretty close to us.”

During a visit to San Francisco in December 1942, the soft-spoken, courteous Miller explained, “I forgot all about the fact that I and other Negroes can be only messmen in the Navy, and are not taught how to man an antiaircraft gun. Several of the men had lost their lives—including some of the high officers—when the order came for volunteers from below to come on the upper deck and help fight the Japanese. Without knowing how I did it, it must have been God’s strength and mother’s blessing, I ran up … and I started to fire the big guns. I actually downed four Japanese bombers.” Some witnesses said that Miller may have actually shot down five aircraft, although the actual extent of any damage inflicted on the Japanese is unknown.

Dorie fired unflinchingly at the enemy raiders for about 15 minutes before running out of ammunition. Then he was ordered to leave the crippled ship. After helping to rescue more shipmates, he dived into the harbor and swam to safety ashore. Dorie had to swim part of the way underwater, beneath burning oil leaking from the Arizona and other nearby ships.

Recognition by the Press: “The First Negro Hero”

In the wake of the disaster at Pearl Harbor, the press and stunned Americans searched for heroes as compensation and morale builders. The Navy obliged, and newspapers carried stories about the heroism of men like Admirals Bennion and Kidd and Chief Watertender Peter Tomich, who sacrificed himself in the boiler room of the capsizing battleship Utah so that his crew could escape. But the acts of bravery at Pearl Harbor were all attributed to whites, except for one newspaper story about an unnamed “Negro mess attendant.” The “Jim Crow” Navy of the time was not ready for a black poster boy.

When America found itself suddenly at war on December 7, most blacks were ready to lend support, despite their second-class citizenship. Less than 24 hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People declared, “Though 13 million American Negroes have more often than not been denied democracy, they are American citizens and will, as in every war, give unqualified support to the protection of their country. At the same time, we shall not abate one iota of our struggle for full citizenship rights here in the United States. We will fight, but we demand the right to fight as equals in every branch of military, naval, and aviation service.”

Dorie Miller’s heroism went unnoticed for more than three months, when his identity was announced by Lawrence Reddick, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York. Suspecting an intentional oversight by the Navy, he wrote to the Navy Department and asked if Miller’s name could be released so that it could be added to his center’s “honor roll of race relations.” The Navy relented, and Reddick was able to publicly announce on March 12, 1942, the acts of America’s first black World War II hero.

Led by the radical Militant, the Chicago Defender, and other black newspapers, the press ran stories about the humble messman who had risked his life to save a white officer. Some newspapers referred to him as “Dorie Miller, the first Negro hero,” and America’s non-white community was quick to embrace him as a model, along with world heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, track star Jesse Owens, and singer-actor Paul Robeson. The black newspapers focused unceasingly on Miller’s exploits, and civil rights groups demanded that he be awarded the Medal of Honor. He would have been the first black to gain the nation’s highest decoration in the two world wars. Meanwhile, the Navy now regarded Dorie Miller as acceptable for recruitment posters.

Songs and Rallies for Dorie Miller

Buttons bearing his image were sold in black communities, and folk songs were composed about him. One fanciful ballad told of how Dorie was “peeling sweet potatoes when the guns began to roar,” and how he grabbed a gun when he saw his captain “lying wounded on the floor.” Another rough-hewn ditty went thus:

In nineteen hundred and forty-one

Colored mess boy manned the gun

Although he had never been trained

Had the nerves ever seen

God willing and mother wit

Gon’ be great Dorie Miller yet

Grabbed a gun and took dead aim

Japanese bombers into fiery flame

He was aiming the Japs to fight

Fought at the poles to make things right

Fight on Dorie Miller I know you tried

Did your best for the side ….

I love Dorie Miller cause he’s my race.

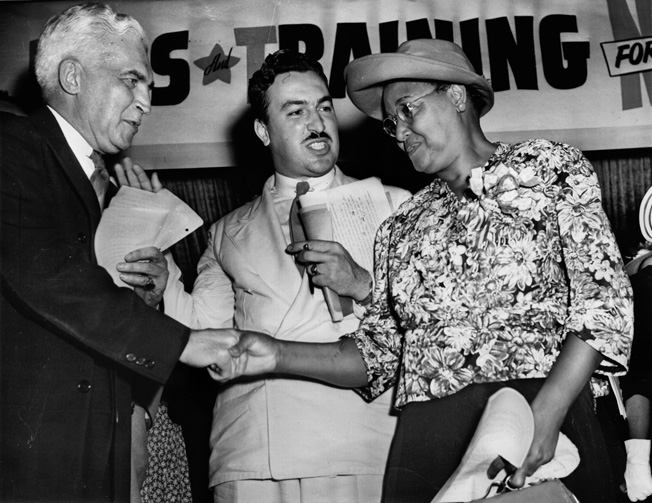

At a “Unity for Victory” rally of 6,000 people in Harlem in June 1942, Dorie’s mother, Henrietta Miller, said, “Some say we colored people have nothing to fight for. We all have something to fight for. We have freedom to fight for. But we can’t fight this war by ourselves. We’ve got to put Jesus into it, for He has never lost a battle.”

A Decorated Ship’s Cook

Her son, meanwhile, was assigned to the 9,950-ton heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis on December 13, 1941, and promoted to mess attendant, second class and first class, and then ship’s cook, third class. He served aboard the Indianapolis for 17 months.

commander in chief in the Pacific, pins the Navy Cross on Seaman Dorie Miller during a ceremony at Pearl Harbor on May 27, 1942.

After being belatedly commended by Navy Secretary Frank Knox on April 1, 1942, the proudest moment in Dorie Miller’s life came on Wednesday, May 27. In Pearl Harbor, not far from where salvage work was proceeding on the hulk of the West Virginia, he stood on the windswept flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise to be decorated along with several other heroes of the opening battles of the war.

As he pinned the Navy Cross on Miller’s chest, Admiral Nimitz declared, “This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race, and I’m sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts.” Miller would also be awarded the Purple Heart, the American Defense Service Medal with fleet clasp, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. The War Department later sent the young hero on a national tour to promote enlistments.

Miller completed his 17 months of duty aboard the cruiser Indianapolis when she returned to the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, on May 15, 1943. A few weeks later, he was assigned to his fifth ship, the brand new escort carrier USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56). One of the Casablanca-class “jeep carriers” being mass-produced in the Henry J. Kaiser shipyards, the 14,000-ton, thin-skinned flattop had been launched on April 19, 1943, and commissioned on August 7.

Dorie Miller on the USS Liscome Bay

Dorie Miller was aboard when the Liscome Bay headed for her first operation in the western Pacific war zone. Her skipper was Captain Irving D. Wiltsie, and she flew the flag of Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinix, the commander of Task Group 52.3. Comprising the escort carriers Liscome Bay, Corregidor, and Coral Sea, with a total of 48 Grumman FM-1 Wildcat fighters and 36 Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers, the group was a component of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance’s U.S. Fifth Fleet.

Admiral Mullinix’s force was assigned an important role, along with other carrier groups, in a major American offensive, Operation Galvanic, in the Gilbert Islands, 2,300 miles from Pearl Harbor. The escort carriers’ primary function was to protect attack transports when Tarawa and Makin Atolls were invaded on November 20, 1943, by Maj. Gen. Julian C. Smith’s 2nd Marine Division and Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith’s 27th Infantry Division, respectively. Planes from the Liscome Bay and her sister flattops shielded the transport ships during the landings and then flew many sorties in support of the troops ashore. The islands were taken after three days of bitter fighting and heavy losses for the Marines.

Admiral Mullinix’s three jeep carriers fought gallantly in the Gilberts during their first action. They were three hectic days and nights for Dorie Miller, his shipmates, and the Liscome Bay squadron (VC-39), and they expected that November 24 would bring more of the same. But time was running out because the enemy was closer than anyone realized.

“The Entire Ship Seemed to Explode”

During the night of November 23, a Japanese Mitsubishi G4M Betty bomber dropped flares to illuminate the American flattops for an aerial torpedo attack. By coincidence, a newly arrived enemy submarine, the I-175, was stalking the CVEs, and the flares gave her a clear view of the Liscome Bay, then cruising near Butaritari Island. Aboard the flattop on November 24, flight quarters was sounded at 4:50 am and general quarters at 5:05 am. Her pilots and air crewmen began to climb into their planes.

Five minutes later, Lt. Cmdr. Sunao Tabata’s submarine took advantage of a gap left by two escorting destroyers, USS Hull and USS Franks, which had been detached, and loosed a spread of torpedoes at the Liscome Bay. One of them struck the flattop’s starboard side between the forward and after engine rooms. Two violent explosions rocked the carrier, and a column of bright orange flame rose 1,000 feet. Fragments of the ship and airplanes were hurled into the air, and debris rained on other ships as far as 5,000 yards away.

The flattop had been struck in the worst possible spot, the room where her bombs and torpedo warheads were stowed. The after portion of the ship was ablaze, and half of her had virtually disintegrated. More explosions shook the flattop, and she continued to burn furiously.

“The entire ship seemed to explode,” reported Ensign D.D. Creech aboard the USS Coral Sea, “and the interior of the ship glowed with flame like a furnace.”

Twenty-three minutes after the first hit, the Liscome Bay sank stern first. She was the first of six U.S. Navy escort carriers to be sunk in the war. Her loss stunned the Navy.

Only 55 officers and 217 sailors were rescued by destroyers. A Navy report of the loss quoted witnesses as saying, “It was a miracle that anyone managed to escape such a roaring inferno.” Among the 644 men who went down with the Liscome Bay were Admiral Mullinix, Captain Wiltsie, and Dorie Miller. The quiet-spoken, humble Navy Cross winner was listed as missing after the sinking, and he was not officially presumed dead until November 25, 1944.

The Legacy of Dorie Miller

Miller’s death was a big shock for the black community, which by then had become increasingly active in the war effort thanks largely to the efforts of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and black labor leader A. Philip Randolph. The messman’s heroism on the USS West Virginia inspired blacks in their struggle for dignity and the right to serve on equal terms in the segregated armed forces. As Willie Wright, a disc jockey in New Haven, Connecticut, said later, “I used to see pictures of Miller in the church I attended as a youngster, and I wanted to learn more about him.”

Remembering the sacrifice of Dorie Miller, increasing numbers of black men and women flocked to work in aircraft factories, munitions plants, and shipyards. One million blacks, including 600,000 women, toiled in defense plants during the war.

The burly, humble Navy Cross winner who had led the way for American blacks to take their place in the Allied struggle against tyranny was remembered. On June 30, 1973, the Navy commissioned a Knox-class frigate named the USS Miller, and a memorial plaque was dedicated by the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority in the Miller Family Park at Pearl Harbor on October 11, 1991.

Bravery and sheer guts know no color.

RIP, Dorie Miller.