By Bob Cashner

Animals of several kinds were used during WW2 by the military forces of belligerents both large and small. For instance, despite Nazi propaganda films of mechanized Blitzkriegs consisting of panzers and half-tracks, in reality the majority of the German Army’s artillery was still horse drawn.

The list of animals used by the various militaries around the world was diverse and, in some cases, a little odd. In addition to draft horses, pack mules, and carrier pigeons, animal warriors also included Finnish reindeer and camels. When it came to versatility, however, warriors of the canine variety saw service in the widest and most diverse array of military roles, such as message carrying, patrolling, guarding, tracking, mine detecting, search and rescue, and even as antitank weapons.

Military Breeds of Choice

For their war dogs, the British Royal Army Veterinary Corps preferred the Alsatian, which is merely another name for the German shepherd, but also used dobermans, airedales, and rottweilers. Later, they found high pedigrees to be less important than originally thought. Mongrels with Alsatian blood and even some outright mutts could learn and perform quite well and were capable of being quiet, dependable, and rugged.

The hands-down favorite of the United States Marine Corps in the Pacific Theater was the doberman pinscher. The Doberman Pinscher Club of America organized the Marines’ “recruiting drive” and the Dobermans became the official dog of the USMC. They were nicknamed, perhaps inevitably, Devil Dogs, from the German nickname for the American Marines during combat in World War I.

Of the U.S. Army’s war dogs, according to the Quartermaster Corps, “In 1942 and 1943, when practically all of the dogs were trained to perform the comparatively simple tasks involved in sentry duty more than thirty breeds of both sexes were considered suitable for military service. Experience revealed, however, that even for sentry duty some breeds were unsatisfactory. Among these were Great Danes, whose large size made them difficult to train, and hunting breeds in general because they were too easily diverted by animal scents. By the fall of 1944 the number of preferred breeds had been reduced to seven, German shepherds, Belgian sheep dogs, doberman pinschers, farm collies, Siberian huskies, Malamutes and Eskimo dogs. Crosses of these breeds also were acceptable.”

The Germans regarded German shepherds as the canine “Master Race” and well over half of their war dogs were of this breed, although Doberman Pinschers and other breeds were also used in lesser numbers.

Training the Dogs in WW2

The German Army had special eight-week schools for training their dogs in WW2, beginning with testing the animals’ potential at age six months. For this early examination, the weeding out process required the potential doggy recruit to follow his owner day or night across different terrain, to behave properly in climbing stairs, in going into a darkened room, in crossing ditches and streams, on hearing gunfire, and more. Timid dogs were instantly eliminated from the program.

The Allies had similar initial testing and found that gun shyness alone washed out roughly a third of the potential war dogs right from the beginning. The standard American and British dog training programs were usually of six to eight weeks’ duration for sentry dogs, but for those performing more specialized missions training could last up to 12 weeks.

American Army war dogs fell under the auspices of the Quartermaster Services, and their special niche became known as the K-9 Corps. Schools were set up around the country for training courses. Of course, the Army produced a manual on the subject: Technical Manual; TM 10-396, War Dogs, 1 July 1943.

The British dogs belonged to the Royal Army Veterinary Corps, which had an excellent source of practical knowledge to draw upon when it came to training their war dogs, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The famous Mounties in their isolated and far-flung posts had trained and worked with canines in conjunction with their police duties for many years before the war in an era when police dogs were otherwise unheard of.

Like their charges, dog handlers were also specially selected from men who had finished their basic military training. A solid prerequisite was for men who were both friendly and sympathetic to dogs; a dog sensed handlers who were not, and the animal’s willingness to perform greatly declined. German schools called for Hundefreunde—dog lovers—and spent approximately as much time on training the handlers as they did the dogs.

The Reliable Messenger Dog

Use as messengers was the most common and often the most important role for dogs in WW2. The Germans, in fact, selected only the smartest of their canine recruits for this duty. They provided scent trails for their messenger dogs to follow, using a 10-to-1 mixture of water and a molasses-like substance smelling like root beer, which they dribbled from a container that left a few drops per meter.

British and American training and use of messenger dogs involved two handlers. One would stay at headquarters or a command post while the other handler took the dog to its destination. When released with a message, the dog would return to the other handler. Thereafter the dog could find its way from one handler to the other by memory.

Allied forces considered a messenger dog’s maximum range to be about eight miles, usually less. One famous Wehrmacht German shepherd named Caesar was the record setter, delivering a message over 101/2 miles in 32 minutes. Each side stressed reliability of messenger dogs over speed. No matter the speed, they would always be faster than a human runner.

During the Italian Campaign, the mountainous terrain made even laying wire communications extremely difficult in some areas, and here there were cases where war dogs were used to help their competition by pulling wire up slopes too difficult for men to clamber up. Such was the landscape that in extreme cases The headquarters of the American Fifteenth Army noted the use of dogs for communication in its after action reports.

Guard and Patrol Dogs

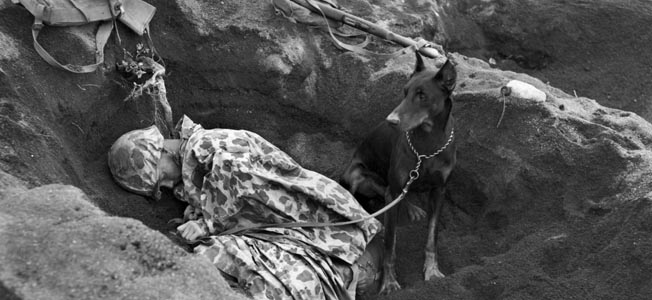

Dogs used in conjunction with reconnaissance patrols were known variously as tracker dogs by the Germans, patrol dogs by the British, and scouts by the Americans. These dogs were used mostly at night, moving usually 30 to 40 yards ahead of the human patrollers, and were specially trained to make no noise whatsoever. When the dog scented enemy personnel, it pointed like a bird dog or returned to its handler. The handler could roughly determine the distance to the enemy by the dog’s level of excitement.

United States Marines and soldiers in the Pacific Theater from corporal to colonel were almost universal in their praise of the scout dogs assisting them in their battles with the Japanese, from the jungles of the South Pacific to the black sands of Iwo Jima, as indicated in comments from after action reports.

“The idea of all patrol members is that these dogs are of a great value. The lead scouts have great confidence in their knowledge that the dog’s instincts are far more acute than their own.”

“In my opinion the dogs are very valuable on patrols into unfamiliar territory. Their alert usually comes long before the scouts could detect any enemy presence. However, I would recommend that after alerting the patrol the dog should be moved back into the patrol while the rifle scouts make a detailed reconnaissance of the area. The dogs are too valuable to risk keeping forward after the initial alert.”

Sentry or guard dogs were also widely used by both the Axis and Allies. These dogs were found to rely more on sight and sound than smell and needed to be retrained if they were to perform tasks that required scenting and trailing. They were used to safeguard field positions such as command posts, airdromes, and supply dumps, and the Germans made an additional note of their use in guarding important industrial facilities against sabotage. When they were available, American forces found a three-man dog team to be more effective on perimeter guard than a six-man squad.

In the Pacific and the China-Burma-India Theaters, guard dogs were found particularly useful. Japanese soldiers were particularly adept at infiltrating through friendly lines in the dark and often avoided detection by human sentries. Not so the sentry dogs with their keen noses and hearing.

The most sinister of the guard dogs were those of the dreaded German Schutzstaffel, or SS. Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler was himself a dedicated German shepherd owner, and that breed quickly became the mainstay of the SS war dog program. Every concentration camp had its own SS dog detachment, with the animals trained to viciously attack inmates, the fear of such aggression serving, according to Himmler, “to encircle prisoners like a flock of sheep and so prevent escape.”

America’s Dog Paratroopers at the Bulge

One often overlooked war dog was the draft animal. Some of the minor warring nations had dogs trained to pull small, two-wheeled carts full of machine-gun ammunition or other supplies. Draft dogs were especially popular with the German Gebirgsjaeger (mountain troops), who utilized them to pull carts or sleds in rough, mountainous country. Canadian and American dogsled teams were used to locate and rescue many downed pilots in Newfoundland, Greenland, Iceland, and Alaska where the treacherous northern weather made ferrying American-built aircraft to other fronts a hazardous undertaking. Often, messenger dogs carried small amounts of vital supplies on their return trips from headquarters.

In the deep snow, thick forests, and rugged terrain of the Ardennes during the Battle of the Bulge, the mechanized and motorized American forces found they could not find or get to the wounded in many tough areas. Colonel Norman Vaughan, already famous in sled dog circles, flew in 200 sled dogs, mostly Malamutes and Huskies, as well as their mushers, from Arctic commands, intending to use them as dog sled ambulances. The only way to get them quickly to where they were needed by the ground forces was to drop them by parachute. His superiors dismissed this ridiculous idea, but the personal intervention of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., saved the plan and the dogs became paratroopers.

The first active duty airborne dog, however, was supposedly a British collie named Rob, who was purported to have made 20 combat jumps while serving with the British Special Air Service commandos in North Africa.

Soviet Dog Mines Against German Tanks

The strangest and most gruesome use of war dogs came on the Eastern Front. In early 1942, Operation Barbarossa found the Soviets hard-pressed. They had lost vast numbers of tanks and antitank weapons in 1941, their industries were in the process of relocating to the Urals, and they were desperate for anything to stop the German panzers. Enter the dog mine; dogs were trained to run under enemy tanks with anti-tank mines attached to their backs.

Dogs were fitted with a canvas body harness rather like a version of the modern dog backpacks. To the harness was attached to either a wooden box or packets of high explosive, as much as 25 pounds. A wooden dowel known as a tilt rod detonator protruded upward from the dog’s back to trigger the explosives when it crawled beneath a panzer, in theory destroying the tank with a blast to the thin bottom armor. This method was, obviously, a single-shot weapon.

The idea may have looked good on paper, except to the poor dogs, but it left something to be desired when put into practice in combat.

Training involved feeding the dogs beneath tanks. However, the smells, sounds, and sights of a Soviet tank were quite different from those of a German tank. In the fog of war, with explosions and bullets flying, it was not unrealistic for the dogs to become confused or panicked. They were just as likely to run under a friendly tank as an enemy tank. Additionally, once the German Army learned of the Hundminen the intelligence was quickly disseminated throughout the front and orders were given to shoot all dogs on sight. While there were a few successes, the idea was short-lived indeed, although it was reported that the Viet Minh later attempted to use dog mines against French vehicles in Indochina.

Medical Dogs of WWII

A more noble and humanitarian task that was common during World War I was the use of first-aid or Medical Corps dogs. These animals located wounded men among the dead and saved countless lives. Russian medical dogs of World War I were trained to drag wounded men to safety. This mission was continued mainly in the European Theater during World War II, most notably in the casualty-heavy fighting on the Eastern Front.

German first-aid dogs were trained to ignore men who were standing or walking and concentrated only on men lying on the ground. When a wounded man was found, the dog seized his holder, a short strap hanging from his collar, and ran back to his handler. The handler then leashed the dog, who led the medics back to the wounded soldier.

The British found search-and-rescue dogs of great value on the home front. In 1940, when Britain stood alone before the might of an undefeated Nazi Germany, the Luftwaffe droned over the isles dropping bombs on the cities below in an unsuccessful effort to break the will of the British people. Civilian casualties mounted to over 40,000 dead and more than three times that number wounded. Soldiers, firemen, and police used dogs to find survivors in the rubble of the bombed-out buildings.

Chips’ Heroic Charge

World War II even had canine heroes who were official members of some units, received their own ranks, and were awarded decorations for bravery. American doggie daredevils included Chips, a mongrel of shepherd, collie, and husky heritage with a penchant for doughnuts, who served with the 3rd Infantry Division. On the Sicily beachhead, the tired soldiers who had slogged ashore with Chips stopped for a breather when they found shelter, they thought, behind a ruined pillbox. In violation of the cardinal rule of his K-9 training, Chips broke away from his handler and ran away. The men found out the reason for this outrageous breach of etiquette a moment later when one of the Germans’ dreaded MG-42 machine guns opened up on them. The gun, however, quit firing momentarily before it could inflict any casualties. Advancing on the machine-gun nest, the GIs found Chips, despite a bullet wound received in his charge, holding down the German gunner by his throat and thus “encouraging” the surrender of the rest of the gun crew.

Combatant nations treated animals as both allies and enemies. They played important roles as combat auxiliaries, and presented a formidable problem as pests and disease carriers. And so, the legacy of animals in the World War II goes far further than the grave of Brian, the paratrooper dog.

I feel bad for the german machine gunner who Chips mauled imagine a dog coming at you and biting your neck scary as hell right?