By Mike Phifer

It had been a brutal winter for the French Army of Portugal. War and hunger had haunted the occupiers, causing their number to dwindle by the thousands. The army, under Marshal Andre Massena, had boasted 65,000 men when it set out during the previous summer of 1810 with orders from Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte to invade Portugal and drive the Duke of Wellington’s English army into the sea. This was the third French attempt to capture Portugal, and things had started well enough for the reluctant Massena, who had been called out of retirement by Napoleon to lead the Portuguese offensive. The formidable Spanish fortress of Ciudad Rodrigo, located near the border, fell in early July 1810. Almeida came under siege next and held out until a chance French shell blew up the ammunition magazine, forcing the fort to surrender on August 28. With these two key fortifications in French hands, the drive for Lisbon could begin in earnest.

After gathering 15 days’ worth of rations, Massena got his army moving on September 15. It was a difficult advance. Plagued by peasants who had bitter memories of the last time the French were in their country and by the ordenança, local levies who constantly harassed them on the march, the French soldiers pushed on over rough roads that took a heavy toll on horses and gun carriages. On September 27, Massena attacked Wellington, whose roughly 50,000 British and Portuguese troops were positioned along the 10-mile-long Busaco Ridge, 100 miles due north of Lisbon. Massena mistakenly believed that he was facing Wellington’s rear guard. The ensuing attack against entrenched defenders cost the French a staggering 4,500 casualties, including five generals. Wellington lost 1,200 men but held the high ground until the following night, when he withdrew after learning that Massena had found a path that would allow him to flank the ridge.

Massena continued his march on Lisbon, stopping for three days to sack the city of Coimbra. As the French pushed on through the fall rain, they were in for an unpleasant surprise. On the morning of October 11, French cavalry patrols spotted the impressive Lines of Torres Vedras. The three defensive lines consisted of 152 mutually supporting fortifications and redoubts. The first two lines stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Tagus River, blocking the approach to Lisbon, while the third protected the port of St. Julian, located at the end of the Lisbon Peninsula.

Wellington had more surprises in store for the French. He had instituted a scorched-earth policy in Portugal, destroying all food and livestock that could not be carried back to his lines. Mills, ovens, and bridges that could be used by the French were destroyed as well. The orders were not entirely implemented, as Portuguese peasants hid some of their food in caves or walled it up inside buildings while driving some of their livestock into the hills.

Realizing that he could not break through Wellington’s defenses, Massena stubbornly waited outside the Lines, hoping something favorable would happen. There was a chance that political uncertainty in England might aid the French. King George III had relapsed into madness, and his son, the Prince of Wales, had taken over with limited powers. The prince was known to favor the Whig opposition to continued British presence on the Iberian Peninsula, and it was thought that he might dismiss Tory Prime Minister Spencer Perceval’s government and replace it with Whigs who would pull the army out of Portugal. For the time being, at least, the crown prince declined.

The French Trail of Horror

For a month Massena kept his army outside the Lines, while his men swept the countryside for any provisions they could find. The army then retreated 25 miles to a strong position and continued to forage for food. Portuguese militia and ordenança unmercifully harassed French foraging parties, killing stragglers and cutting Massena’s communications with Spain. Massena managed to get a pessimistic report to Paris in November, but orders came back from Napoleon for him to hold on. Meanwhile, Massena’s men battled hunger by rooting out hidden provisions stored by the peasants, using torture and murder if necessary to get them to reveal their meager caches.

By January 1, 1811, Massena had almost 20,000 fewer men than when he invaded Portugal, giving him a mere 46,600 functional soldiers. He was losing an additional 500 men a week to hunger, sickness, and Portuguese guerrillas. With no help coming from Marshal Nicolas Soult’s army in southern Spain, which was besieging the Spanish fortress of Badajoz, Massena ordered preparations for a retreat in late February. The army was issued 15 days’ worth of biscuits, with orders not to eat them until the retreat began. Some units near starvation could not wait. On March 4, Massena’s army began its retreat.

A trail of horror and death was left by the French in their retreat. “Nothing can exceed the devastation and cruelties committed by the enemy during his retreat: he has set fire to all the villages and murdered all the peasantry for leagues on each flank of his march,” commented Maj. Gen. Thomas Picton, commander of the British 3rd Division. On March 11, Wellington’s crack Light Division, made up of the 43rd and 52nd Light Infantry, the green-coated soldiers of the 95th Rifles, and the 1st and 3rd Caçadores (Portugese light infantry), came into contact with the French VI Corps under Marshal Michel Ney, who was directing Massena’s rear guard defense at Pombal. For the next five days, the two contingents battled each other sporadically while the French retreat continued.

Low Supplies, Slow Retreat

Originally, Massena had planned to cross the Mondego River and forage for supplies north of Coimbra while waiting for reinforcements. This plan was dashed by Colonel Nicholas Trant and six battalions of English militia, which blocked the French from using the fords across the river. A French attempt to get across the bridge at Coimbra failed as well. When the French rear guard was maneuvered out of Condeixa, 10 miles away, Massena abandoned plans to cross the Mondego. Instead, he reluctantly resumed his retreat.

On March 15, the Light Division battled Ney’s rear guard at Foz do Arouce, where Ney had left three brigades on the British side of the 100-yard bridge spanning the Ceira River. While the 3rd Division moved on the French left, the Light Division attacked the right, managing to get riflemen between the French 39th Regiment and the bridge. The French soldiers, seeing their danger, panicked. Hundreds attempted to retreat by swimming the river. Ney quickly restored the situation and drove off the British riflemen who were threatening the bridge, but not before the French suffered 250 casualties, many of whom drowned in the swiftly flowing river. Adding insult to injury was the loss of the 39th’s eagle standard, which had been given to the regiment by Napoleon himself. It was later fished out of the river by the gleeful British.

The French retreat continued. To speed it up, Massena abandoned many of his wagons and hamstrung a large number of draft and pack animals. By March 22, Massena’s army was at Celorica, less than 20 miles from the Spanish border. By then, Wellington’s pursuit had slowed down as well; he was having supply problems of his own.

Massena was not willing to retreat completely from Portugal just yet. He ordered his ragged soldiers, many of whom had no footwear other than cowhide moccasins, to swing southeast toward the Tagus, an area with no supplies and few roads. Ney fiercely opposed the order, insisting that the army should continue the retreat into Spain to rest and resupply. He not only refused to obey Massena’s order, he informed the apoplectic commander that he intended to march his own men to Almeida. Massena immediately relieved Ney of command and ordered him to the rear to await further orders from Napoleon.

Proving Ney’s judgment correct, the French march toward the Tagus lasted less than a week before lack of food ended the operation. On March 29, the Army of Portugal resumed its retreat eastward. At the start of the new month, Massena’s hold on Portugal consisted only of Almeida and the area between the Coa River and the Spanish border.

“Fight on, My Brave Lads; We Shall Beat Them”

On April 3, Wellington struck General Jean Reynier’s isolated II Corps at Sabugal, which was holding the French left. The nearest help was seven miles away. Wellington’s plan called for the Light Division to ford the Coa and hit Reynier’s flank and rear. A frontal attack across the river was to be carried out by the 3rd and 5th Divisions, backed by the 1st and 7th Divisions when the French seemed on the verge of retreating.

A thick fog in the Coa valley hampered visibility and troop movement. Lt. Col. Sydney Beckwith took his brigade of the Light Division across the river but, due to the heavy fog, crossed too far to the left. Instead of striking the French rear, he collided with the enemy flank. The 43rd Regiment and some guns moved across the river to support Beckwith. The Light Division’s temporary commander, Maj. Gen. Sir William Erskine, became overly cautious after sending Beckwith across the river and prevented a second brigade from crossing as planned. Erskine then rode off with the cavalry, his negative part in the battle done. Beckwith with 1,500 troops now faced two full enemy divisions on his own.

A veteran officer, Beckwith handled the situation commendably. His men beat back a French counterattack, but it soon became obvious to Beckwith that he would have to give ground to the French, who heavily outnumbered him. He ordered his men to pull back, telling them not to hurry. Instead, he said casually, “We’ll just walk quietly back, and you can give them a shot as you go along.” Despite a wound to the head, Beckwith stayed with his men, encouraging them with the words: “Fight on, my brave lads; we shall beat them.”

He was right, but more help was needed. Four British divisions crossed the Coa and attacked the French front, which was held by 3,000 determined troops. After the loss of 760 men, Reynier was forced to retreat. The British suffered 161 casualties. Except for Almeida, Portugal now was virtually liberated from the French.

Weakened and Spread Thin

Wellington was convinced that Massena was retreating to Ciudad Rodrigo and maybe even farther east to Salamanca. The duke, however, did not intend to strike too far into Spain, since his own supply convoys were slow and plagued by delays. His first concern was to take Almeida and, if possible, Ciudad Rodrigo. Wellington hoped the French would abandon their last holdout in Portugal, but when they didn’t, he had no choice but to set up a siege at Almeida and starve the garrison into submission, which in the duke’s estimation would take four weeks.

Wellington attempted to blockade Ciudad Rodrigo as well. He directed Julian Sanchez, a Spanish guerrilla leader, to take his band beyond the stronghold and watch the road to Salamanca, warning the Light Division if any large French convoys headed toward the fort. Erskine received just such a warning on April 13, but his characteristic tardiness allowed a French division and convoy to reach Ciudad Rodrigo unmolested. With the fort reprovisioned, Wellington abandoned his efforts against the French stronghold.

Wellington’s forces were spread thinly over 100 miles of rough country. In all, he had only about 35,000 soldiers to blockade Almeida and watch Massena. The French Army, too, was in rough shape as it limped into Salamanca. The time in Portugal had cost the French 25,000 men. Of these, 8,000 were prisoners and another 2,000 had been killed in combat, while the rest had perished of famine, disease, and the vengeance of the ordenança.

Two weeks of rest did the men a world of good, but Massena’s army was still weak in cavalry and artillery horses—about a third of the troopers lacked proper mounts. The artillery had even worse problems, with only enough horses to pull 20 guns and their complement of vehicles. Massena petitioned Marshal Jean Bessieres, commander of the district, for assistance. Bessieres came grudgingly to Massena’s aid, personally bringing him two small brigades of cavalry, a horse artillery battery, and 30 teams of horses for Massena’s guns. “He would have done better to have sent me a few thousand men more, and more food and ammunition, and to have stopped at his own headquarters, instead of coming here to examine and criticize all my movements,” grumbled Massena to his staff.

Fuentes de Onoro

By April 26, Massena was back at Ciudad Rodrigo with his reorganized army of four corps. Massena’s army now consisted of 42,000 infantrymen, 4,500 cavalry, and 38 guns, making a less-than-grand total of 48,000 men. Although the soldiers had been resupplied, rearmed, and reshod, morale remained low. The men lacked confidence in Massena and were still unhappy over the popular Ney’s abrupt dismissal. Nevertheless, on May 2 the Army of Portugal crossed the bridge over the Agueda at Ciudad Rodrigo and divided into two columns, once more heading west. The cavalry led the way, while II Corps took the Marialva Road and VIII and IX Corps advanced on the Carpio Road. VI Corps acted as reserve.

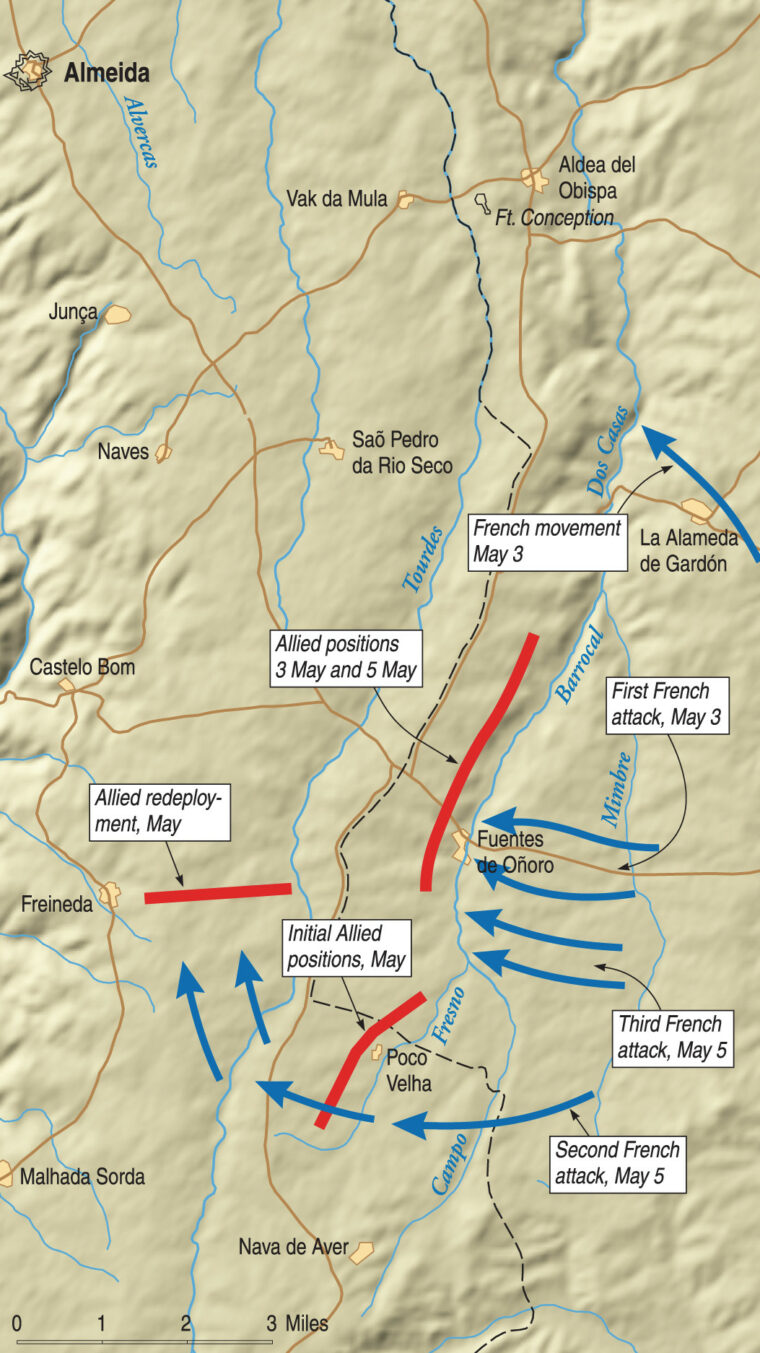

Wellington, who had been absent from his army since April 16, returned on the 28th and immediately began preparing to face Massena. With his Light Division and cavalry skirmishing before the French advance, Wellington moved to block the French relief force. The duke positioned his force along an eight-mile line behind the Dos Casas River from the village of Fuentes de Onoro to the ruined Fort Conception. The ravine of the Dos Casas was deep and wide, while upriver it became shallower toward Fuentes de Onoro, which was located on the west bank of the river. The village was ideal for defense—Wellington’s forte—as the houses and gardens were surrounded by stone walls.

On May 3, the Light Division and cavalry were driven back onto Wellington’s position by the advancing French. On the left flank of the allied army, just south of Fort Conception, was the 5th Division. Guarding the division’s flank were some 300 Portuguese cavalry. The 6th Division moved into place in front of San Pedro. Both divisions had a deep ravine to their front, making their position even more formidable. To the south were the 1st, 3rd, and 7th Divisions, occupying the heights above Fuentes de Onoro. The Light Division was stationed in reserve, while four British cavalry regiments, numbering about 1,500 troopers, were posted south and to the rear of Fuentes de Onoro. In all, Wellington had 34,000 soldiers, 1,800 cavalry, and 48 guns with which to stop Massena.

By the afternoon, most of Massena’s army was visible to the allies. The French were in three columns, with Reynier’s II Corps opposing Wellington’s left at Fort Conception and San Pedro. General Andoche Junot’s VIII Corps, reduced to one division as the other was guarding communications elsewhere, made up the center column. The bulk of the French forces made up the left column facing Fuentes de Onoro. It consisted of General Louis Loison’s VI Corps with General Jean Baptiste Drouet’s IX Corps in the rear, out of view of the British. The French cavalry, meanwhile, moved to the left to face the British cavalry.

After measuring Wellington’s position in the early afternoon, Massena determined that the enemy’s right was too strong to attack due to the formidable terrain. Fuentes de Onoro was the key to the enemy position, but the French marshal was not sure of the disposition of Wellington’s troops, situated behind the crest of the hill. All that were visible were skirmishers on the high ground and the red- and green-coated soldiers holding the village itself.

Around 2 pm, Massena ordered the 10 battalions of General Claude Ferey’s division to storm Fuentes de Onoro. Reynier, to the north, was ordered to make a feint against the British 5th Division around Fort Conception. Wellington ordered his Light Division toward Fort Conception to counter Reynier’s II Corps, but it soon became clear there was no serious threat in this area. The main fight was at Fuentes de Onoro.

Taking the Village at All Cost

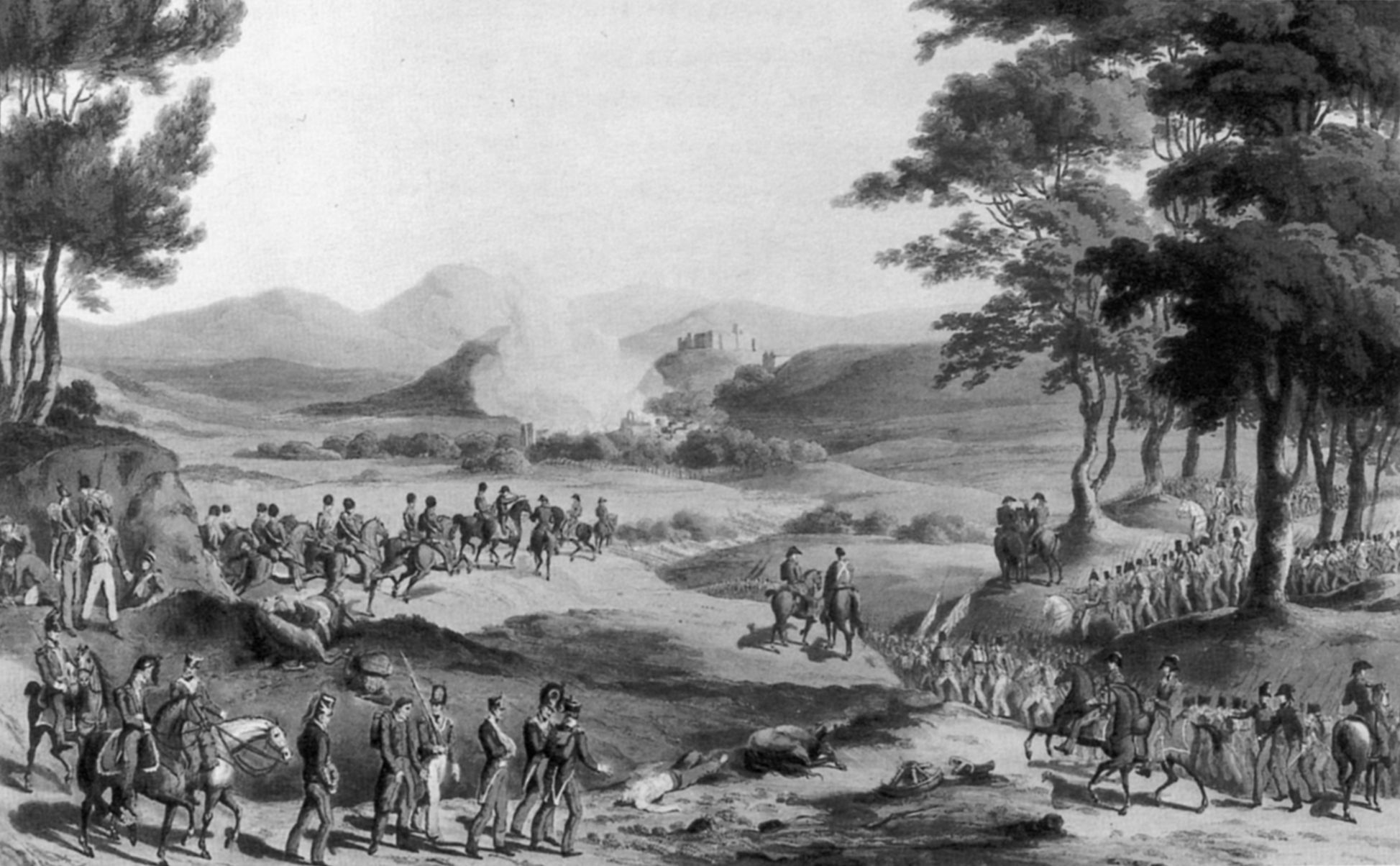

The first brigade of Ferey’s divison splashed across the knee-deep stream and managed to capture some buildings despite taking heavy fire. Wellington, who was close by, sent in Colonel Henry Cadogan’s 71st, supported by the 79th and 24th Regiments. Cadogan’s force hit the French hard, and in bitter street fighting drove them out of the village across the Dos Casas to their side of the river. The Scottish troops captured a small chapel and a few gardens on the east side of the stream, but they were unable to hold them when Massena ordered his defeated troops back along with four fresh battalions from General Jean Marchand’s divisions of the VI Corps in support. They retook the small chapel and drove Cadogan back across the Dos Casas, but could go no farther. Nightfall brought an end to the fighting, which had cost the French 652 casualties. The allies had suffered 259 killed and wounded.

Massena, after being repulsed in a frontal assault, looked for a way to flank Wellington. He ordered General Louis-Pierre Montbrun to head south and reconnoiter Wellington’s right, checking the terrain and position of enemy troops. By afternoon, Montbrun reported that Wellington had only cavalry pickets south of Fuentes de Onoro. Wellington’s right ended at Nava de Aver, which was held by Sanchez’s guerrillas.

Massena intended to turn Wellington’s right. To do so, he would use Marchand’s and Julien Mermet’s divisions from VI Corps and General Jean Solignac’s division from VIII Corps—17,500 troops in all. Most of his cavalry, 3,500 troopers under Montbrun, would also take part in the flanking attack. Massena’s plan called for Reynier to make a feint against Wellington’s left. The attack was to be pressed if the enemy seemed weak in this area. Fuentes de Onoro was to be attacked by Ferey’s division again, along with the two divisions from Drouet’s IX Corps when the turning movement was observed to the south. The village was to be taken at all cost.

Clash of Cavalry

Across the Dos Casas, Wellington had his troops under arms by early morning. Although shooting broke out across the Dos Casas at Fuentes de Onoro, it died out around 10 am. An informal truce allowed the wounded and dead to be removed. No fighting resumed for the rest of the day. Wellington, meanwhile, suspected that the French might attempt something on his right. He moved his four cavalry regiments, under Maj. Gen. Stapleton Cotton, in that direction and sent the 7th Division to cover the right, with two battalions positioned at Poco Velha and the woods nearby. The remaining seven battalions were situated west of Poco Velha on a slope. The entire division, 4,000 men, was about two miles from Wellington’s main position.

Wellington withdrew the light companies from Fuentes de Onoro and left the two Scottish battalions, the 71st and 79th, to hold the town, while the 24th acted in support on the hill. The Light Division was moved back to its original position behind the village. Back in command of the Light Division was Maj. Gen. Robert Craufurd, who had just returned from leave. With the coming of dusk on the 4th, the French were ready to strike hard at Wellington.

A thick mist on the morning of May 5 was gradually dispelled by the sun, but not before Sanchez’s guerrillas at Nava de Aver were caught off guard by French cavalry and quickly retreated. Two squadrons of the British 14th Light Dragoons, which had moved up to support them the night before, did not join the Spaniards. Instead, they put up a running fight for two miles against heavy odds. They were finally driven back to Poco Velha, where two battalions of the 7th Division were posted. A volley from troops posted in the woods stopped the French in their tracks.

The main French cavalry advance was farther to the north of Nava de Aver. Facing them was a squadron of 16th Light Dragoons and one from the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion, acting as a line of observation. In a brave but rash move, the 16th Light Dragoons charged into the mass of French cavalry and suffered heavy casualties. The Germans charged next and were also forced back. The two broken squadrons galloped to Poco Velha and reformed on the flank of the village. The French cavalry soon appeared in overwhelming numbers and showed every intention of turning the British right, despite the fact that 12 squadrons of Wellington’s cavalry were forming in the woods near Poco Velha.

It was now about an hour after daybreak when the French infantry joined in. Formed in double columns, Marchand’s division appeared from behind a hill of Nave de Haver and moved toward Poco Velha. They pushed into the woods and drove out the British and Portuguese skirmishers. Then they stormed Poco Velha itself and forced out the British 85th Battalion and the Portuguese 2nd Caçadores, which fell back in disorder and were charged by French light cavalry. Casualties were heavy for the British and Portuguese, who suffered 85 killed or wounded and another 70 men captured. It might have been worse had not two squadrons of the German Hussars charged in to cover them. The two battered units formed up and moved toward the main body of their division a mile away.

Wellington Adjusts His Forces

The situation was beginning to look grim for Wellington. French infantry divisions emerging from Poco Velha were now threatening to drive a wedge between Fuentes de Onoro and the rest of Wellington’s army. Montbrun’s cavalry was already in pursuit of the lone allied division. Help was soon on the way in the form of Craufurd’s Light Division, which Wellington personally chose to go to their rescue.

While the Light Division headed south, Wellington realigned his troops. The 5th and 6th Divisions remained where they were positioned and the two Scottish battalions continued to hold Fuentes de Onoro. At the same time, the 1st and 3rd Divisions, along with some Portuguese troops, formed a new line behind the village running west instead of north-south. Fuentes de Onoro, or more accurately the hill where the church sat, was the pivot of the allied army which now formed an L shape. Wellington’s line of communication was lost due to this move, but the duke as always meant to fight.

The British cavalry on Wellington’s right, meanwhile, continued to fight an outnumbered running battle against Montbrun’s four French cavalry brigades, while the 7th Division took up new ground on a slope that was mostly bare except for some rocks and stone walls. The British cavalry was forced back to the 7th Division and relocated on the left rear of the infantry. The foot soldiers faced the French cavalry on their own.

Montbrun attempted to break the English infantry. While skirmishers harassed Maj. Gen. John Houston’s front and light artillery shelled his center, dragoons attempted to roll up his right. The Chasseurs Britanniques, a unit originally made up of French Royalists and later reinforced with French prisoners of war, fired a volley from the cover of a stone wall, driving back the French horsemen. Another cavalry charge was beaten back by the 51st. The French cavalry could do nothing against the 7th without infantry help. Unfortunately for Montbrun, Marchand’s and Mermet’s divisions were not marching to his aid, but rather heading directly for Wellington’s new line west of Fuentes de Onoro.

About this time, Craufurd’s Light Division arrived, buying time for Houston to march his division to a new position on Wellington’s right, extending the English line across the Turon River toward the village of Freneda. With the 7th Division gone, Craufurd had the difficult task of getting his men across open ground back to the main line under the noses of French cavalry and artillery. He formed his battalions into close columns and put a few companies of riflemen and Caçadores in the scrub on the flanks. He then headed across the plain slowly and in perfect order.

During the two-mile withdrawal, French cavalry swarmed about but kept a respectable distance from Crauford’s squares. Whenever the French guns moved in to fire at Craufurd’s men, the British cavalry would force them to retire. Craufurd and his men made it back safely back behind the 1st Division, but not before the French cavalry managed to cut off some skirmishers, killing or wounding 80 men and capturing another 20. Two squadrons of the 14th and Royals managed to drive off the French and rescue the rest of the skirmishers.

The French cavalry finally drew back, and long-range artillery opened up on Wellingon’s right, with the British guns quickly replying. Marchand’s and Mermet’s divisions were soon within artillery range of the British opposite the 3rd and 1st Divisions. Fuentes de Onoro, now the anchor of Wellington’s left, remained in English hands.

Fuentes de Onoro Holds

While things were going well on the southern flank for the French, Ferey’s division launched against Fuentes de Onoro two hours after dawn. The French stormed the village, driving back the two Scottish regiments holding it. At the upper end of the town, the Scottish troops rallied and with the help of the 24th pushed the French back to the lower houses of the village, where the fighting came to a temporary standstill.

Drouet ordered three battalions made up of grenadiers of his two divisions into the foray. In hard fighting they rooted out the defenders from behind stone walls and barricaded houses and drove them back up the hill near the church. The grenadiers’ attack stalled when Wellington fed light companies from the 1st and 3rd Divisions and the 6th Caçadores into the grim battle, halting the French advance.

It was now around noon, and Drouet meant to finish the bloody business in Fuentes de Onoro. He ordered in two fresh divisions that made their way up the body-strewn streets. The situation was becoming more and more serious for Wellington. Fierce fighting raged in the churchyard among the tombstones, and the 9th French Light Infantry managed to push to the church itself.

The nearest troops were Maj. Gen. Henry Mackinnon’s brigade, forming part of the second line of the British 3rd Division, which was facing Marchand. Mackinnon sent Sir Edward Pakenham off to find Wellington to get permission to retake the village. Pakenham, who located Wellington not far away, galloped back, waving his hat with word from the commander to attack. Leaving the 45th to hold the line, Mackinnon led the 74th and the 88th Regiments, known also as the Connaught Rangers, into battle. The Connaught Rangers, led by Colonel Alexander Wallace, slammed into the 9th French Light Infantry, putting their bayonets to good use. After a brief stand, the French broke, hotly pursued by the Rangers.

The 74th quickly charged into battle behind them. The beleaguered remnants of the two Scottish regiments and the light companies joined in the attack. Savage fighting swept through the narrow bloody streets of the village. More than 100 French grenadiers were wiped out by the Rangers, who caught them in a cul-de-sac. The French were swept from the village and driven across the Dos Casas. Some of the Allied troops splashed across the stream after the French and were killed on the far side. Fresh French reserves came forward to cover the rout, but made no attempt to recapture the village although French guns continued to pound away at long distance.

“We Should Have Been Beat”

It soon became clear that the lower houses of Fuentes de Onoro along the Dos Casas could not be held due to French artillery fire. A new defensive position was set up in the upper part of the village. It was about 2 pm, and the decisive fighting for Fuentes de Onoro was over.

In all, the fighting on May 5 cost Massena 2,192 casualties. Wellington suffered 1,545 killed, wounded, or captured. It had been a hard-fought battle for both sides. Wellington would later admit that, had Napoleon been there, “We should have been beat.” But the emperor was back in France, and Massena, his “favored child of victory,” was the Iron Duke’s opponent. Still, it was a close-run thing for the allies.

That night Wellington began to entrench his position. Massena made no further move against the formidable English position. Instead, he sent his cavalry north and west to attempt to find a way through the duke’s defenses. They found none. Wellington could not be maneuvered from his position, and Almeida could not be relieved. Massena ordered the supplies intended for the besieged garrison to be distributed among his soldiers instead.

With that, Massena retreated safely to Ciudad Rodrigo. There, on May 10, word arrived from Napoleon that Massena had been relieved of command. Massena was not sorry to hear it; he would claim later that fighting Wellington had turned him “gray all over.” The new commander, Auguste Marmont, would have no better luck against Wellington. More bloody fighting lay ahead before Spain, too, would be liberated from the French invaders.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments