By Glen Jeansonne, Frank C. Haney, and David Luhrssen

General George S. Patton, Jr., was one of the most flamboyant and controversial figures of World War II. His career was also one of the most thoroughly documented of any of the war’s great commanders. Historians have had a treasury of material at their disposal as Patton was a prolific writer, kept personal diaries, and saved virtually every scrap of paper he ever handled. Additionally, his family and heirs have gone to great lengths to preserve the artifacts of his existence. Even with such voluminous, detailed, and often extremely personal material available on Patton, it was not until the 1980s that historians began to form a clear picture of the hidden elements that made up the man.

“A Genius of War”

Historians will inevitably examine the past through the lens of their own time; likewise, historical figures present themselves to their contemporaries according to the knowledge and prejudices of their epoch. Patton, who was always concerned about shaping his public image according to his own lights, did not care to call attention to his dyslexia; nor did those who wrote about his swashbuckling exploits as a tank commander in the aftermath of World War II care to investigate the subject, despite such red flags as the frequent symptomatic idiosyncrasies in his spelling and punctuation. Given the state of medical science in the 1940s and the postwar era, Patton could not have been aware that he may have also suffered from an affliction known today as attention deficit disorder (ADD), which afflicts many dyslexics; nor could historians have identified the condition until recently. Even the importance of Patton’s early family life, which led him to valorize war and model himself as the heir of his heroic Confederate ancestors, was neglected until recently.

Martin Blumenson brought the general’s dyslexia to attention in his 1985 biography Patton: The Man Behind the Legend. Historian Carlo D’Este enlarged upon Blumenson’s pathfinding work in his 1995 study Patton: A Genius for War, painting more clearly a picture of an oddly functioning Patton family that had shaped Patton’s entire life and ultimately enabled him to overcome, or a least deal with, his dyslexia and embark on a storied military career.

In trying to understand Patton’s career, we cannot afford to discount those aspects of his life that had long been hidden behind his martial bluster. Patton’s dyslexia and perhaps ADD, his immediate forebears, his unusual upbringing, and his early socialization developed the young Patton into what D’Este called “a genius for war.”

Evidence of Patton’s Conditions

The fact that Patton had dyslexia is supported by his family and documented by both Blumenson and D’Este. That Patton also had ADD will probably remain a matter of conjecture and speculation, although in his public life he exhibited many of the disorder’s behavioral symptoms: his flexibility and willingness to shift strategy, such as the quick deal he cut in Casablanca permitting the formerly Vichy forces to continue governing Morocco under Allied auspices in November 1942; his tirelessness when in pursuit of a tangible goal, as when he took command of the moribund II Corps in Tunisia in February 1943 and rapidly transformed it into a formidable fighting force; his boredom with mundane tasks, expressed in a 1916 letter during the garrisoning of the Mexican town of Dublan when he wrote his father, “We are all rapidly going crazy from lack of occupation and there is no help in sight”; and his startling ability to visualize and make ideas concrete.

Other ADD symptoms include poor impulse control, extreme mood swings in response to events, and short excessive tempers, all of which Patton displayed as a commanding officer, sometimes notoriously, as with his infamous slapping incidents during World War II in which he was accused of abusing enlisted men. The frustrations experienced by a person dealing with either dyslexia or ADD can be overwhelming and can often lead to serious self-doubt, feelings of inadequacy, bouts of uncontrollable anger, and emotional hypersensitivity.

Dyslexia, which is often characterized by difficulty reading and by the transposition of letters or numbers, is considered to be a learning disorder. Having dyslexia, however, does not mean that a person lacks intelligence. Quite the contrary, many dyslexics are extremely intelligent and struggle mightily with the symptoms of the disorder. The dyslexic often has a different or unique mind-set, is often gifted and productive, but learns and perceives in a way different from others.

Both dyslexia and ADD have a genetic component. They are hereditary and run in families. In this light, perhaps George Patton’s genealogy is more important that even he imagined.

Growing up in Lake Vineyard

Patton was born on November 11, 1885, in San Gabriel, California, near Los Angeles, to doting parents from a financially comfortable background. His father spent several terms as district attorney of Los Angeles and ran unsuccessful campaigns for other public offices, including one as a Democratic candidate for Congress. In 1885, the year of George’s birth, he gave up the practice of law to take over the affairs of his deceased father-in-law’s business empire in an attempt to save it from the mismanagement of another relative. By 1899, the business was in foreclosure and new owner retianed the elder Patton as manager for many years. Despite all difficulties, no effort was spared by Patton’s father in providing a “proper” and, indeed, aristocratic upbringing for his children.

During George’s youth, the Patton family lived both in Los Angeles and at Lake Vineyard, the estate of his late grandfather, Benjamin “Don Benito” Wilson, an early American pioneer in California before the territory became part of the United States.

Blumenson credits Don Benito with some of the genetic makeup of the future general, including looks, driv, and tenacity. D’Este’s work reveals Don Benito as an extremely eccentric and physically rugged individualist. His exploits included lassoing and killing grizzly bears, surviving the poison-tipped arrow of an American Indian, and delivering the heads of rebellious Indians in a wicker basket to California’s governor. Patton would replicate that feat when he presented General Pershing with the bodies of three of Pancho Villa’s men during the Punitive Expedition of 1916. Like his ancestor, George Patton enjoyed and displayed a zest for combat, which contrasted sharply with his more low-key superior in World War II, General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Don Benito was a man of frightful temper who did not suffer fools and finally gave up carrying a gun lest he do something rash. There is more than just a suggestion that George S. Patton, Jr., owed a great deal genetically to Don Benito.

His environment shaped the young Patton as much as his heredity. The atmosphere of his childhood included the continual repetition of family lore that glorified participation in lost causes such as the Confederacy and the struggle for Scottish independence among his more distant forebears and emphasized the Pattons’ ties to the Southern planter aristocracy. There was also an ongoing exposure to the great military leaders of history and literature, of whom George learned while being read to by his family from Walter Scott, Rudyard Kipling, Homer, and other authors. In addition, a parade of famous martial figures visited his home as guests of his parents.

The building blocks of the general’s personality were laid out in Lake Vineyard, a place of open spaces, horses, and outdoor action.An expert horseman at an early age, George established himself as an accident-prone risk taker in his riding and childhood war games. He remained a magnet for accidents through his military career, from a tent fire that singed his face during the 1916 Mexican Expedition to auto accidents in the waning months of World War II. Patton’s military proclivity became evident at an early age. His father carved him a wooden sword, and the boy played continually with his sister and an abundance of cousins and friends who visited the Vineyard estate. Patton once said, “I must be the happiest boy in the world.”

Aunt Nannie

One of the more eccentric fixtures in the Patton household was George’s Aunt Nannie. When Ruth Wilson married the boy’s father, George Patton II, her sister, Annie, was devastated. Annie had fallen deeply in love with George II. Her sanity not quite intact and her love unrequited, Aunt Nannie, as she was known, nevertheless attached herself to the newly married couple and never left them. D’Este tells us that she shared everything in their marriage except the bed.

While his parents doted on George, Aunt Nannie was obsessed with him. She became a surrogate mother who shamelessly spoiled him. Nannie was the uncontested, often tyrannical ruler of the Patton household, often trying the Pattons’ patience with her refusal to allow George to be punished.

While George’s father amused him by reading the Iliad and the Odyssey, Aunt Nannie, having decided that George was “delicate,” began reading aloud to him classics such as Plutarch’s Lives and The March of Xenophon and stories about Alexander the Great and Napoleon. D’Este asserts that it was Nannie who deeply influenced his early education. George was a willing participant who listened attentively and absorbed deeply. The most influential work Nannie presented to George was the Bible, which she read him three or four hours a day. Jesus emerged from her exegesis as the quintessential example of human courage.

Nannie was never certain if her efforts were having any effect on her nephew and even came sadly to the conclusion that he was dim-witted. Until he started school at the age of 11, he was unable to read or write. Surprisingly, he could quote from memory not only lengthy Bible passages, but also entire volumes of poetry and long passages of history. Nannie’s unrelenting Bible readings caused the book to become the foundation on which George’s life was built. God dominated Patton’s speeches and his writings throughout his life and especially during the peaks and valleys of his career.

The Pattons’ Civil War Prestige

Where Aunt Nannie left off, Papa took over with vivid, lavish, and probably exaggerated tales of Confederate heroes of the Civil War. The dead colonels, George and Waller “Taz” Tazewell Patton, came back to life as Papa told and retold the stories of their heroic lives given willingly, tragically, in the cause of the South. The Pattons might now live in California, but emotionally they never left the Virginia plantations. It was Papa who taught George of his family heritage through the lives of Patton military men from the Revolution through the Civil War.

As assiduously as Aunt Nannie thumped the Bible and force-fed the classics, so with military history and family lore did Papa stoke George’s all-consuming fires. Papa was vicariously living his own truncated military career through his son. Sometimes he produced actual heroes for his son to emulate. Colonel John Singleton Mosby, the Confederate guerrilla who by the 1890s was a lawyer for the Southern Pacific Railroad, was a frequent visitor to the Patton home. He regaled the young boy with tales of the Civil War and the bravery of the Confederate Pattons.

Also among the living touchstones was George’s own beloved step-grandfather, Colonel George Hugh Smith, whose quiet counsel and tales of the Civil War instilled a profound sense of destiny in the boy. Blumenson and D’Este have noted that Smith may have been the greatest influence on Patton’s decision to become a soldier and continue the family’s martial legacy.

Papa was also willing to get down and play soldier with George. On occasion, the boy would wield his wooden sword against Papa, who would match his own father’s sword against his son’s. Papa also made sure that George learned to ride a horse sitting in the saddle from which Colonel George S. Patton had fallen fatally wounded during the Civil War. All told, the relationship between father and son was such that minor transgressions were willingly admitted and just as readily forgiven by the indulgent parent.

Learning with Dyslexia

George’s childhood prepared him to become a secure adult who knew what he owed the world and what he wanted from it. His place was securely at the top of respectable society, and although flawed and tormented, he never doubted his status. Blumenson writes that Patton’s position brought him a sense of superiority, a tinge of snobbery and racism. Patton was determined to realize his exalted, noble heritage. All his life, he honed his mannerisms—the profanity, arrogance, aristocratic bearing, the scowl, and the ruthlessness. And Blumenson says, “… the process killed his sensitivity and warmth and turned a sweet-tempered child into a seemingly hard-eyed and choleric adult.”

George’s early education was not unusual in his time, when children of privilege often were tutored at home until a relatively advanced age. Early on, however, his parents discovered their child had a learning disability that hampered his ability to read. Today that disability is recognized as dyslexia, a malady first identified in 1896, one year before the 11-year-old George entered the Classical School for Boys in Pasadena, unable to read or write. Dyslexia did not become widely recognized in the United States until the 1920s, well into Patton’s career as a military officer.

Dyslexia is not simply a matter of reversing letters or numbers but is a complicated disorder whose symptoms include hyperactivity, obsessiveness, mood swings, difficulty in concentrating, impulsiveness, and compulsiveness. Because of their effort to overcome difficulty in reading and writing, dyslexics can be driven by a compulsion to succeed. Yet, they often harbor feelings of inferiority. Virtually every common symptom of dyslexia can be found in the adult Patton. “I am either very lazy or very stupid or both for it is beastly hard for me to learn,” he told his future wife, Beatrice Banning Ayer, while still a cadet at West Point. This was despite his prodigious intellectual powers and ability to recall enormous bodies of text and information.

The Classical School for Boys, where Patton spent six years getting his first formal education, catered to children of the Southern California gentry. Patton was a diligent student who nevertheless struggled and faltered with algebra, geometry, and arithmetic because of his dyslexia. Drawing from his family-tutored knowledge, his marks in ancient and modern history were consistently high.

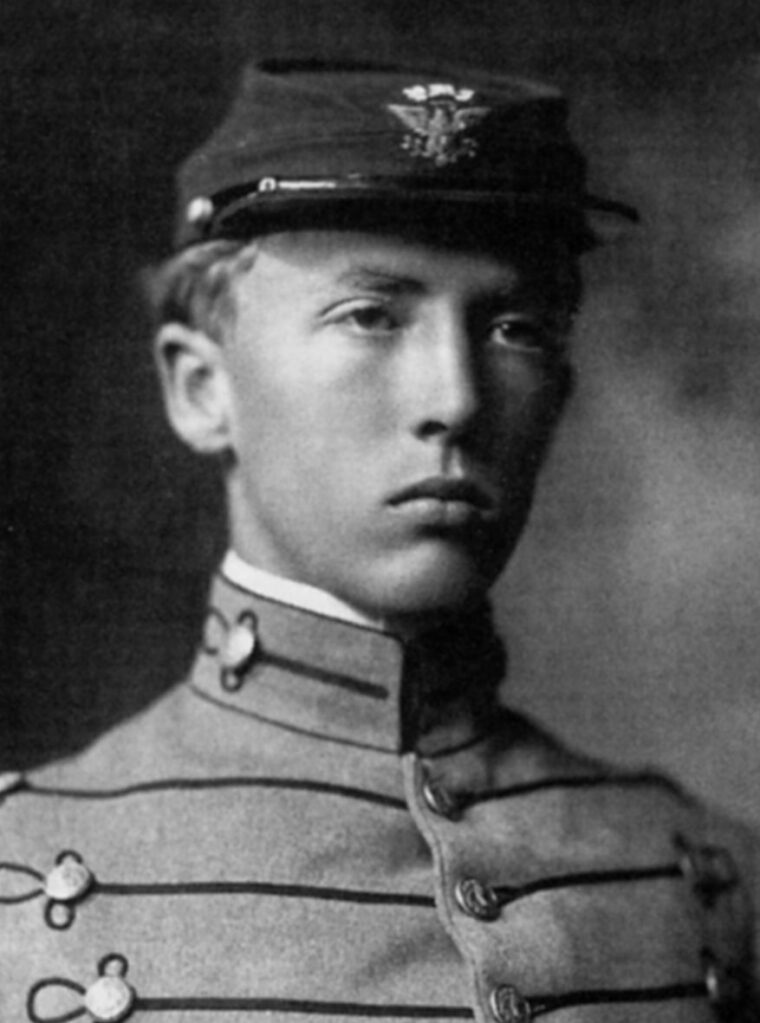

Patton at the Virginia Military Institute

His family was hardly surprised when George announced in 1902 that he would become an Army officer. Given so many years of indoctrination in the family heritage, his father surely would have been shocked if George had chosen any other profession. The family encouraged George to seek admission to West Point rather than Virginia Military Institute, the alma mater for three generations of Pattons. VMI remained an alternative, however, as entry into West Point was hardly guaranteed. Given the Patton presence at VMI since its founding, admission there was a certainty despite George’s mediocre school record.

Although his father attempted to pull every political string within reach, George was unable to secure a spot at West Point, and in September 1903 he started classes at VMI. This would give Papa another year to line up the political assistance he would need to crack the West Point barrier.

The trip to VMI was by train, and the strange and obsessed Aunt Nannie was part of the entourage, along with his parents. She set up housekeeping near VMI for the entire school year. The ritual of Aunt Nannie following her “son” from place to place was to become one of the more bizarre aspects of Patton’s family life.

VMI and George Patton suited each other well, partly because his father had prepared him impeccably, but also because George applied himself with a vengeance. His military work rose above that of his classmates, and his academic marks were good, even if he was struggling. Knowing that his dream of West Point could slip away, he redoubled his efforts, and his grades steadily improved. He was aided by the dyslexic’s need to strive hard to overcome all impediments.

Meanwhile, Papa worked tirelessly to win George’s appointment to West Point, and on March 4, 1904, he received a telegram informing him of success. Upon tendering his resignation from VMI, Patton learned that he would have been appointed first corporal at VMI had he returned. This signal honor was conferred on the outstanding plebe. By the time he entered West Point, Patton had taken a passable performance at the Classical School and forged it into an impressive one at VMI. The first real and significant challenge of Patton’s life had been conquered by dint of hard work and perseverance.

Pompous Patton

As at VMI, Aunt Nannie remained for the duration in close proximity to West Point and her beloved George. George believed that most of his fellow cadets at the academy were socially inferior to his classmates at VMI. He never lost his aversion to those of alleged inferior social status, a snobbish trait his grandson Robert ascribes to Patton’s father, who “considered himself to be of better stock, therefore of better character than most other men.” Patton himself wrote to his father that most “were nice fellows but very few indeed are born gentlemen…. The only ones of that type are Southerners.”

Patton’s caste consciousness was exceeded only by his bouts of mood swings, self-doubt, and self-aggrandizement. In numerous letters and conversations with his father, George alternately berated and then praised himself for one deed or another. All the while, Papa gave patient, judicious, and loving counsel to his son and provided support, advice, and reassurance whenever asked. Never judgmental, always analytical, he was the lens that allowed George to see his problems clearly. The only other people who could fulfill this need were Beatrice Ayer, the future Mrs. Patton, and the doting Aunt Nannie, whose odd presence George did not seem to mind at all. She provided a more immediate springboard for his emotions, doubts, and rages than the letters of Papa or Bea.

D’Este concluded that Patton was torn between an ability to see future greatness for himself and the possible effects of his dyslexia, which served unceasingly to implant the notion that he was both ordinary and stupid.

Patton’s classmates perceived him as pompous and overambitious. His penchant for self-promotion, honed razor sharp at West Point, lasted intact for a lifetime. His goal was glory, and any means to that end was fair. He aspired to become the first general from his class, an admirable goal but a tactless gaff when announced. His first command at West Point, as first corporal, was short lived. He was busted back to sixth corporal when he made himself foolish by putting more men on report than any other corporal. He could not understand why his over-the-top military style would be punished and vowed that he would never allow any slack under his command. Yet, in doing so he moderated his behavior so that the same fate would not befall him again. Throughout his career, he cultivated friendships and unabashedly called in markers, using his social status and whatever tools he could muster to promote himself.

Thriving with his Dyslexia

There were setbacks. Failing math, a typical hurdle for dyslexics, Patton was forced to repeat his plebe year, something he desperately wanted to avoid. This served two purposes: first to reinforce his feelings of inadequacy, and second to drive him to new heights of perseverance. It was at about this time that Patton began keeping a diary. He and his family had a habit of saving virtually every scrap of paper, every souvenir, and every trophy he ever acquired. The diary carried this a step further. When combined with volumes of his letters, pamphlets, poetry, and other communications, it has left historians with detailed indicators of the man. Even this was not without design on Patton’s part. The first diary carried a note from Patton that it would be important to a biographer some day. Prescience or arrogance? Perhaps both.

In his final year, Patton was named to West Point’s second highest rank, corporal adjutant. He was now in his element. In the class of 1909, Patton would graduate 46th out of 103 cadets. Upon graduation, he would marry Beatrice, the daughter of a Boston Brahmin and textile magnate, thereby validating his own aristocratic upbringing and instantly making him the wealthiest officer in the U.S. Army. Patton had survived into adulthood and, if he had not overcome his dyslexia, he had at least learned to thrive in his dyslexic world.

George Patton’s unique upbringing was the correct formula for bringing out the best in a dyslexic person. It provided the only way for him to become a historic figure of his stature. It would have been far more likely, given the extent of his disability, that Patton would become anonymous and marginal. Each person in George’s life played a vital role in his development, and the absence of any one of them could have left him unfavorably equipped for any meaningful career in a society that misunderstood his condition. Each of them, no matter how eccentric, outrageous, perfect, or flawed, provided a learning environment tailored for the combination of brilliance and disability that was George Patton.

This is a fascinating article which may help to explain how brilliant Gen. Patton could be in planning strategies and knowing how to execute them, through his grasp of military affairs and history going back to what his family told him, to his neverending struggle with problematic traits that he constantly had to work to overcome, sometimes failing and producing drastic results. I read Blumenson’s book years ago (still have it), but combined with D’Este’s more recent work this article helps to explain how such a talented, complex person could be privately tortured by what is now seen as a disabilty. Thank you for posting this, I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. Patton is to be respected, dispite his shortcomings, for working to overcome his problems and becoming one the best generals this country was very fortunate to have when needed.