By John Walker

The city of Hue was the capital of a unified Vietnam from 1802 until 1945. With its stately, tree-lined boulevards, Buddhist temples, national university, and ornate imperial palace within a massive walled city known as the Citadel, Hue was the cradle of the country’s culture and heritage. As late as 1967, Hue remained an open city, unscathed by the various wars that since World War II had raged up and down the Indochinese peninsula. But when Communist leaders in North Vietnam felt compelled to alter their strategy and launch a massive offensive in South Vietnam in early 1968, the Battle of Hue City suddenly placed the city into of some of the heaviest fighting of the entire Vietnam War.

Stung by reversals on southern battlefields and fearful of an American invasion of their homeland, North Vietnam’s Politburo members voted to abandon protracted-war tactics and mount a three-phase general offensive that would reverse the course of the war against the South Vietnamese and their American allies. When Defense Minister and Chief of Staff General Vo Nguyen Giap, vanquisher of the French in 1954 after a brutal eight-year war, voiced opposition to the offensive, command was given to General Nguyen Chi Thanh, leader of Communist Viet Cong guerrilla forces in South Vietnam. When Thanh died unexpectedly, Giap reassumed command and rapidly massed six North Vietnamese Army infantry divisions in South Vietnam’s northernmost province, Quang Tri.

The Tet Offensive Begins

In the fall of 1967, Giap launched a series of big battles near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that had two objectives: draw American forces north, away from the heavily populated coastal and lowland cities, and determine if the Americans would respond with an invasion of the north. A massive buildup of Communist troops and equipment in the south began. General William Westmoreland, commander of allied ground forces in South Vietnam, responded by sending more troops and firepower into the northern provinces, but he did not launch an invasion of Laos or North Vietnam. This gave Giap the confidence he needed to order the winter-spring offensive to proceed. Giap would find Westmoreland a far more tenacious commander than France’s Lt. Gen. Henri Navarre, who had allowed 15,000 of France’s finest troops to be surrounded and destroyed at Dien Bien Phu. Westmoreland, for his part, welcomed Giap’s deployment of sizable forces in outlying, sparsely populated areas where America’s massive firepower could be brought to bear.

The main effort of Giap’s preliminary phase began on January 21, 1968, at Khe Sanh in northwestern South Vietnam, where two NVA divisions lay siege to the U.S. Marine combat base there. Believing the Communists might be trying to achieve another Dien Bien Phu, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared that Khe Sanh must be held at all costs. With all eyes on Khe Sanh, the Communists then launched the main offensive in the early morning hours of January 31. Some 84,000 NVA and Vietcong soldiers, brazenly violating the Tet (lunar new year) cease-fire, mounted simultaneous attacks on 36 of 44 provincial capitals, five of six autonomous cities, including Saigon and Hue, 64 of 242 district capitals, and 50 hamlets.

With many South Vietnamese soldiers away on holiday leave, the Communists enjoyed widespread early success—even the grounds of the U.S. embassy in Saigon were breached. Within days, however, all of the assaults in the smaller towns and hamlets were turned back. Heavy fighting continued for a while in Kontum Province, Can Tho, Ben Tre, and Saigon, but after a week the offensive, by far the largest of the war to date, had been essentially halted everywhere except for Hue. There, the longest and bloodiest battle of the Tet offensive began to unfold.

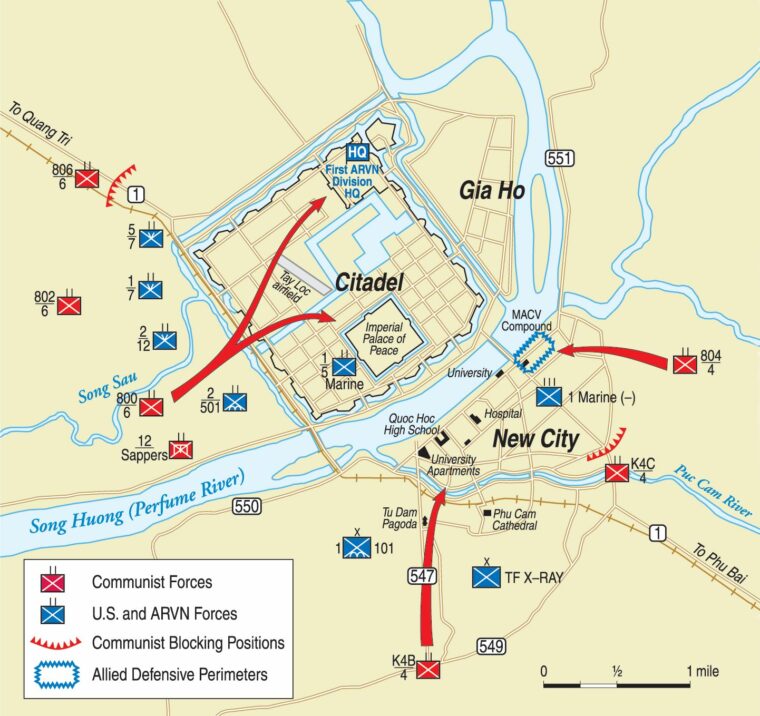

The third-largest city in South Vietnam with a wartime population of 140,000, Hue was located astride National Highway 1 just west of the coast, about 50 miles south of the DMZ, on one of the principal land-supply routes to allied troops. One-third of the city’s citizens lived north of the Perfume River in the Citadel. Just outside the walls of the Citadel to the east was the densely populated district of Gia Hoa. The Citadel was an imposing fortress, covering three square miles with a labyrinth of readily defensible positions protected by an outer wall 30 feet high and up to 90 feet thick. Many parts of the wall were honeycombed with bunkers and tunnels built by Japanese occupiers during World War II. At the south end of the Citadel lay another enclave, the Imperial Palace compound, a square with 20-foot-high walls that measured 800 yards per side.

The 1st ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong, was headquartered in the fortified Mang Ca compound in the northeast corner of the Citadel. Unfortunately for Truong, who was regarded by many American advisers as one of the ablest senior commanders in the South Vietnamese armed forces, over half his division was on holiday leave and out of the city when the Tet offensive erupted. Most of Truong’s remaining units were spread out along Highway 1 from Hue north toward the DMZ. The closest South Vietnamese unit was the 3rd ARVN Regiment, with three battalions, five miles northwest of Hue. The only combat unit inside the city was the division’s Hac Bao Company, known as the Black Panthers, an elite all-volunteer unit that served as the division’s reconnaissance and rapid-reaction force. Security within the city was the responsibility of the National Police.

South of the river and linked to the Citadel by the six-span Nguyen Hoang Bridge, over which Highway 1 passed, lay the New City. This modern section was about half the size of the Citadel and included about two-thirds of the city’s population. It contained the hospital, provincial prison, Hue University, government administration buildings, and the MACV (U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam) compound, which housed 200 American and Australian military advisers to the 1st ARVN Division. The advisers were the only allied military presence in the area when the Battle of Hue City began. Their lightly fortified compound lay on the eastern edge of the city just south of the Nguyen Hoang Bridge.

The nearest U.S. combat base was at Phu Bai, eight miles south on Highway 1. Phu Bai was a major Marine Corps command post and support facility, home to Task Force X-Ray, a forward headquarters of the storied 1st Marine Division. Commanded by Brig. Gen. Foster LaHue, assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division, the task force consisted of two Marine regimental headquarters and three battalions—the 5th Regiment, with two battalions; and the 1st Regiment, with one battalion. LaHue and most of the troops had only recently arrived in Phu Bai from Da Nang and were still getting acquainted with their area of operations when the Battle of Hue City began. There were U.S. Army units in the area as well. Two brigades of the elite 1st Air Cavalry Division (Airmobile), including the 7th and 12th Cavalry Regiments, were scattered over a wide area from Phu Bai in the south to Landing Zone (LZ) Jane just below Quang Tri in the north. The 1st Brigade of the famed 101st Airborne Division, recently attached to the 1st Cavalry Division, had recently arrived at Camp Evans, north on Highway 1 between Hue and Quang Tri.

Opposing the allied troops in the region were at least 8,000 well-trained, well-equipped Communist soldiers. The majority were NVA regulars armed with a vast array of weapons, including brand-new AK-47 assault rifles, RPD machine guns, B-40 rocket-propelled grenade launchers, rockets, mortars, and recoilless rifles. The NVA were backed by six Vietcong main force battalions, including the 12th and Hue City Sapper Battalions (a typical VC main force battalion numbered between 300 and 600 veteran, skilled soldiers). The Communists had prepared extensive plans for the assault on Hue, which would be directed by General Tran Van Quang, commander of the B4 (Tri Thien-Hue) Front. The plan called for a division-sized assault on the city while other units cut off access to block allied reinforcements.

With detailed information on civil and military installations within Hue, the Communists divided the city into four tactical areas and prepared a list of 196 specific targets. Communist assault troops received intensive training in urban warfare tactics before the offensive began. Vietcong cadres also prepared detailed lists of “cruel tyrants and reactionary elements” to be rounded up during the early hours of the attack. The list included South Vietnamese government and military officials, civil servants, American civilians, educators, clergy, foreigners, and other so-called “enemies of the people” who were to be relocated into the jungle outside the city once they were apprehended. The Communists were well aware that the bad weather that traditionally accompanied the northeast monsoon season would hamper allied aerial resupply operations and close air support, which would otherwise have given the allies in Hue a significant advantage.

The Battle of Hue City: How the Siege Began

A wave of premature attacks—possibly launched because North Vietnam’s calendar differed from South Vietnam’s—began shortly after midnight on January 30-31. All five provincial capitals in II Corps and the city of Da Nang in I Corps were attacked. The Vietcong assaults began with mortar and rocket attacks, followed by massed ground assaults by battalion-sized units backed in some areas by NVA regulars. The attacks were not well coordinated, and by daylight almost all the Communist attackers had been driven from their objectives. Although American forces were placed on maximum alert and similar orders were issued to all ARVN units, the allies still responded without any real sense of urgency. Orders canceling leaves came too late or were disregarded. At 3 am on January 31, NVA and Vietcong forces launched a countrywide general offensive.

After learning of the premature attacks, Truong still believed the enemy would not attack Hue directly. Accordingly, he positioned his remaining troops around the city to defend outside the urban area. When the Communist attack began, the only regular ARVN troops inside the city were the Black Panther Company, guarding the Tai Loc airstrip at the northwestern corner of the Citadel. Large numbers of Vietcong guerrillas had already infiltrated the city, mingling with the throngs of people who had come to Hue for Tet. In the early hours of January 31, the guerrillas took up positions within the city and waited to link up with NVA and Vietcong assault troops.

At 3:40 am, the Communists launched a rocket and mortar barrage from the mountains west of the city and followed it with a three-pronged ground assault. A four-man NVA sapper team, dressed in ARVN uniforms, killed the guards and opened the western gate to the Citadel, allowing the lead elements of the 6th NVA Regiment to enter the old city and launch the main attack. As Communist fighters poured into Hue, the 800th and 802nd Battalions of the 6th Regiment rapidly overran most of the Citadel. Truong and his staff held off the attackers at the 1st ARVN Division compound, while the Black Panther Company held its position at the eastern end of the airfield. After the 802nd came close to penetrating the 1st Division compound, Truong ordered the Black Panthers to withdraw from the airfield to bolster his defenses at the division compound. Except for the 1st ARVN Division compound, by dawn of January 31 the NVA 6th Regiment held the entire Citadel, including the Imperial Palace.

Across the Perfume River in southern Hue, much the same situation existed. Allied advisers in the MACV compound awoke in the early-morning hours to the sound of bursting rocket and mortar rounds. Grabbing any weapons that were at hand, the advisers were able to successfully repulse the Communist ground assault on the compound, which lacked the cohesion of the attack against the Citadel. After their initial assault stalled, the 4th NVA Battalion of the 804th NVA Regiment, supported by local guerrilla companies and elements of the Hue City Sapper Battalion, maintained a virtual siege of the compound with mortars, rockets, and automatic-weapons fire.

While fighting raged around the MACV compound, two VC battalions took over the Thua Thien Province headquarters, police station, and other government buildings south of the river. At the same time, the NVA 810th Battalion took up blocking positions on the southern edge of the city to prevent reinforcements from that direction. By dawn, the NVA 4th Regiment controlled all of Hue south of the river except for the MACV compound and the LCU (landing craft utility) ramp on the waterfront northeast of the compound. At dawn on January 31, nearly everyone in the city could see the gold-starred, blue-and-red National Liberation Front flag flying over the Citadel. While Communist troops roamed the streets consolidating their gains, political officers marched with them, reading out names from their blacklists and instructing South Vietnamese and foreigners alike to report to a local school for relocation.

At the same time the Communists were beginning their attack in the Battle of Hue City, the Marines in Phu Bai had their hands full. Enemy rockets and mortars struck the airstrip, and enemy infantry units hit Marine and South Vietnamese units in the region. LaHue received reports of enemy strikes all along Highway 1 between the Hai Van Pass and Hue. Altogether, the Communists struck 18 targets. At this point, LaHue had little reliable intelligence on the situation inside the city. All he knew was that the 1st ARVN Division and MACV compound had been attacked. Because of Communist mortaring of the LCU ramp in southern Hue, the allies stopped all river traffic into the city.

With only a tenuous hold on his own headquarters compound, Truong ordered his 3rd Regiment, reinforced by two airborne battalions and a troop of armored cavalry, to fight their way into the Citadel from their positions northwest of the city. After encountering intense small-arms and automatic-weapons fire, the units managed to reach Truong’s headquarters, arriving in the late afternoon. Costs were high, including 40 killed and another 91 wounded. Meanwhile, a call for reinforcements had gone out from the embattled MACV compound, but the plea was lost in the confusion caused by the simultaneous attacks. Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam, commander of South Vietnamese forces in I Corps, and Lt. Gen. Robert Cushman, III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) commander, were unaware of the enemy’s true strength inside Hue but were all too aware that reinforcements were needed on both sides of the river.

While Lam and Cushman prepared to reinforce their units in Hue, the Communists moved to prevent those reinforcements from reaching the embattled defenders. The NVA 806th Battalion blocked Highway 1 northwest of Hue, while the 804th and K4B Battalions took up positions in southern Hue and the 810th dug in along Highway 1 south of the modern city. Having received no reliable intelligence to the contrary, LaHue believed only a relatively small Communist force had penetrated Hue as part of a diversionary attack. Thus misled, he sent only one company to deal with the situation. Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines (A/1/1) was ordered to move up Highway 1 from Phu Bai by truck to relieve the surrounded advisers at the MACV enclave.

Heading north, the Marines of A/1/1 were joined by four M48 tanks from the 3rd Tank Battalion. When the convoy crossed the bridge that spanned the Phu Cam Canal into southern Hue, the Marines were hit with a withering cross fire from enemy automatic weapons and B40 rocket fire. The convoy was finally halted by the intense Communist resistance between the canal and the river short of the MACV compound. With Company A pinned down, Lt. Col. Marcus Gravel, battalion commander of 1/1, organized a reaction force made up of himself, officers from his command group, and G Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. The relief force pushed north up Highway 1, reinforced by two self-propelled 40mm guns. Meeting light resistance, the force linked up with A/1/1 and, with the aid of four tanks and the 40mm guns, the combined Marine force fought its way to the MACV compound, arriving at 3:15 pm. Ten Marines were killed and 30 wounded.

Gravel received orders from LaHue to cross the Perfume River with his two companies and push through to the 1st ARVN Division compound in the Citadel. Leaving Company A behind to help defend the MACV compound, Gravel took Company G, backed by three of the original M48 tanks and several others from the ARVN 7th Cavalry Squadron, and moved out to comply with LaHue’s orders. Leaving the tanks on the southern bank of the river to provide direct fire support, Gravel and his small group of Marines attempted to cross the Nguyen Hoang Bridge. Another 10 Marines were killed or wounded as the relief force encountered a hail of machine-gun fire from a position at the north end of the bridge.

Two Marine platoons made it across the bridge and turned left, paralleling the river along the Citadel’s southeast wall. They immediately came under heavy fire from AK-47 rifles, machine guns, B40 rockets, and recoilless rifles from the walls of the Citadel. With his outnumbered force pinned down, Gravel was forced to withdraw. After two hours of intense fighting, the company made it back to the bridge, and by 10 pm the 1st Battalion had established defensive positions and a helicopter landing zone near the MACV compound along a stretch of the river. A third of the men in Company G had been killed or wounded.

With Truong fully occupied in the Citadel north of the river, Lam and Cushman agreed that ARVN forces should be responsible for clearing the Citadel and the rest of Hue north of the river, while Task Force X-Ray would take responsibility for the southern part of the city. Since the palace and historical buildings in the city were sacred to the Vietnamese people, the commanders imposed limitations on the use of artillery and close air support to minimize collateral damage, a decision that would lead to difficulties. Eventually, the restrictions would be lifted when it was realized that artillery and air support were needed to dislodge the tenacious Communist defenders from the city.

Cushman moved to reinforce Hue and seal off the enemy inside the city. On February 2, the 1st Air Cavalry Division’s 3rd Brigade was given the mission of blocking enemy approaches into the city from the north and west. The brigade airlifted the 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry, into an LZ six miles northwest of Hue on Highway 1. By February 4, the cavalrymen had moved across country from the LZ and established a blocking position on a hill overlooking a valley four miles west of Hue that provided excellent coverage of the main enemy routes into and out of the city.

Meanwhile, the 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry conducted search-and-clear operations along suspected enemy routes west of Hue. On February 7, they made contact with an entrenched NVA force and tried for 24 hours to expel the Communists. The enemy forces, however, stymied the cavalry’s advance with heavy automatic-weapon and mortar fire. For the next 10 days, the two air cavalry battalions engaged in heavy fighting with the entrenched enemy forces. Although they were unable to dislodge their foes, the cavalry units partially blocked the enemy’s movement and kept the NVA units from taking part in the battle raging within Hue.

The task of getting allied reinforcements into Hue was made more difficult by a change in the weather on February 2. Temperatures fell into the 50s and heavy rain began falling. Gravel’s Marines were ordered to attack and recapture the Thua Thien Province headquarters building and prison, located six blocks west of the MACV enclave. Gravel launched a two-company attack supported by tanks, but the Marines immediately ran into trouble. Heavy sniper fire erupted, along with 57mm recoilless rifle fire, which knocked out one Marine tank. The assault was stopped cold, with the Marines falling back to their position near the MACV building.

LaHue now realized that he had vastly underestimated the strength of the enemy forces south of the river. He called in Colonel Stanley Hughes, new commander of the 1st Marines, and gave him overall tactical control of U.S. forces in the southern part of the city. Assuming control of the battle, Hughes promised Gravel reinforcements and ordered him to conduct “sweep and clear operations to destroy enemy forces, protect U.S. nationals, and restore that [southern] portion of the city to U.S. control.” Accordingly, Gravel ordered Company F, 2/5, to relieve a MACV communications facility near the U.S. consulate that had been surrounded by Vietcong guerrillas. After fighting all afternoon and losing three men killed and 13 wounded, the Marines were unable to reach their objective, taking up night defensive positions and waiting for the morning to renew the attack.

The next day, with additional reinforcements, the Marines finally relieved the MACV radio facility late in the morning. After three more hours of intense fighting, they reached the Hue University campus. During the night, enemy sappers had destroyed the railroad bridge over the Perfume River west of the city but had left untouched the bridge across the Phu Cam Canal. At 11 am, Company H, 2/5, commanded by Captain Ron Christmas, formed a convoy and crossed the bridge over the canal, backed by two U.S. Army trucks mounted with quad .50-caliber machine guns as well as two Marine “Ontos”’ tracked vehicles, each armed with six 106mm recoilless rifles. As the convoy neared the MACV compound, it came under heavy enemy machine-gun and rocket fire, and it responded with heavy fire of its own. Soon, H Company joined Gravel at his position near the MACV building. The NVA and VC gunners continued to pour machine-gun and rocket fire into the Marine positions. At the end of the day, two Marines had been killed and 34 wounded.

On the afternoon of February 2, Hughes decided to move his command group from Phu Bai into Hue, where he could more directly control the battle. Accompanying Hughes in the convoy was Lt. Col. Ernest Cheatham, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, who had been sitting frustrated in Phu Bai while three of his companies—F, G, and H—fought in Hue under Gravel’s command. Hughes quickly established his command post in the MACV compound. The forces at his disposal included Cheatham’s three companies from 2/5 and Gravel’s depleted battalion consisting of A Company, 1/1; a provisional company made up of one platoon of B Company, 1/1; and several dozen cooks and clerks who had been sent to the front to fight alongside the infantry.

Hughes directed Gravel to anchor the left flank with his battalion to keep the main supply route open. He then ordered Cheatham’s three companies to attack south from the university toward the provincial headquarters, telling Cheatham to “attack through the city and clean the NVA out.” Cheatham devised a plan for his battalion to move west along the river from the MACV building, attacking with Companies F and H in the lead and G Company in reserve. He soon found that the plan, though simple, was extremely difficult to execute. The distance from the MACV enclave to the confluence of the Perfume River and the Phu Cam Canal was almost 11 city blocks, each of which the enemy had transformed into a fortress that would have to be cleared building by building, room by room. The last time American Marines had been involved in urban combat had been in Seoul during the Korean War in 1950.

Street by Street, and House by House

The Marines launched their advance toward the treasury building, but made slow progress. Each time they tried to advance, they were hit with a withering array of mortar, rocket, machine-gun, and small-arms fire from prepared positions in the buildings to their front. The Marines simply did not have enough men to deal with the entrenched enemy. By the evening of February 3, they had made little progress and were taking increasing casualties. The next morning, Hughes met with his two battalion commanders. He told Cheatham to continue the attack and Gravel to secure Cheatham’s left flank with his battalion, which now had only one company left after the previous day’s fighting. As Gravel ordered his Marines into position, they first had to secure the Joan of Arc school and church. His men immediately ran into heavy enemy fire and began fighting house to house. Eventually, they secured the school, but they continued taking fire from enemy gunners in the church. Reluctantly, Gravel gave the order to fire on the church, and Marines pounded the building with mortars and 106mm recoilless rifle fire, finally killing off or driving away the defenders.

With Gravel’s men in position to screen his left flank as far as the Phu Cam Canal, Cheatham began his attack at 7 am on February 4. It took 24 hours of heavy fighting just to reach the treasury building. Attacking the rear of the building after blowing holes through adjacent courtyard walls with 106mm recoilless rifle fire, the Marines finally recaptured the treasury. Faced with rapidly deteriorating weather, the Marines found themselves in a nightmarish room-by-room, building-by-building struggle to clear an 11-block area south of the Perfume River. Small groups of Marines moved doggedly from house to house, blowing holes in walls with rocket launchers and recoilless rifles, then sending in fire teams and squads to clear each building room by room.

Progress was slow and costly. On February 5, Christmas’s H/2/5 Marines recaptured the Thua Thien provincial capital building after a particularly vicious battle. Using tanks and 106mm recoilless rifles mounted on mechanical mules (flat-bedded, self-propelled carriers about the size of a jeep), the Marines advanced against heavy automatic-weapon, rocket, and mortar fire. Using their own mortars and CS gas, a crowd-control agent, the Marines overwhelmed the defenders in mid-afternoon. The provincial headquarters had served as the command post of the NVA’s 4th Regiment, and with its loss the Communist defense south of the river began to falter.

Despite the Marines’ quick adaptation to street fighting, it was not until February 11 that the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines reached the confluence of the Perfume River and the Phu Cam Canal. Two days later, the Marines crossed to the western suburbs of southern Hue, aiming to link up with troopers of the 1st Cavalry and 101st Airborne who were moving toward the city. By February 14, most of Hue City south of the river was in American hands, but mopping-up operations would take another 12 days due to continued sniper, rocket, and mortar fire. The fight for southern Hue cost the Marines 38 dead and 320 wounded; the bodies of over 1,000 NVA and VC soldiers were strewn about the city south of the river.

While the Marines fought house to house to retake the southern part of the city, heavy fighting north of the river continued. Despite the efforts of the American units trying to seal off Hue from outside reinforcement, Communist soldiers and supplies continued to flow into the Citadel from the west and north and even on boats coming down the river. On February 1, the 2nd ARVN Airborne Battalion and the 7th ARVN Cavalry recaptured the Tay Loc airfield, but only after suffering severe casualties and the loss of 12 armored personnel carriers. Later that day, Marine helicopters ferried part of the 4th Battalion, 2nd ARVN Regiment, into the Citadel from Dong Ha. Once on the ground, the ARVN attempted to advance but found the going difficult. By February 4, their advance north of the river had essentially stalled among the houses, alleys, and narrow streets adjacent to the Citadel wall, leaving the Communists still in possession of the Imperial Palace and most of the surrounding area.

The NVA Counterattack

On the night of February 6-7, NVA troops counterattacked and forced the ARVN troops to pull back to the airfield. At the same time, the NVA rushed additional reinforcements into the city. Truong responded by redeploying his units, ordering the 3rd ARVN Regiment to move into the Citadel and take up positions around division headquarters. By the evening of February 7, Truong’s forces inside the Citadel included four airborne battalions, the Black Panthers, two armored cavalry squadrons, the 3rd ARVN Regiment, the 4th Battalion of the 2nd ARVN Regiment, and a company from the 1st ARVN Regiment. Despite the heavy buildup of forces, Truong’s units still failed to make any headway against the dug-in North Vietnamese, who had burrowed deeply into the walls and the tightly packed buildings. It seemed that nothing could stem the flow of Communist reinforcements moving into the city.

With his forces stalled, Truong appealed to the Americans for help. On February 10, Cushman ordered LaHue to send a Marine battalion to the Citadel. The next day, after LaHue ordered Major Robert Thompson’s 1st Battalion, 5th Marines to move to the northern part of the city, Marine helicopters lifted two platoons of Company B/1/5 into the ARVN headquarters complex inside the Citadel. A day later, Company A and five M48 tanks, along with a third platoon from Company B, made the journey by landing craft across the river from the MACV compound along the moat to the east of the Citadel through a breach in the northeast wall.

The next day, Company C joined the battalion as well. Once inside the Citadel, the Marines were ordered to relieve the 1st ARVN Airborne task force in the southeastern sector. At the same time, two battalions of Vietnamese Marines moved into the southwest corner of the Citadel with orders to sweep west. Aware of the allied buildup, the Communist forces prepared to hold their positions at all costs. The next day, after he conferred with South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu, Lam authorized allied forces to use whatever weapons were necessary to expel the enemy from the Citadel—only the Imperial Palace remained off limits to artillery and air support.

The mission of the 1/5 Marines was to push their way down the east wall of the Citadel toward the Perfume River, with the Imperial Palace on their right. At 8:15 am on February 13, with heavy rain falling, Company A moved out and followed the wall in the direction of a distinctive archway tower. As the Marines neared the tower, NVA soldiers opened up with rockets and automatic weapons from concealed positions dug into the base of the tower. The thick masonry of the tower’s walls protected the Communist defenders from the heavy fire directed at it. The fresh Marine unit had just arrived, and the men found themselves unfamiliar with city fighting, surrounded by houses, gardens, buildings two and three stories high, and paved roads littered with abandoned vehicles.

After losing 15 killed and 40 wounded, the Marine advance against the south wall stalled; Thompson pulled A Company back and sent in B and C Companies. Once more the Marines were raked by intense small-arms, machine-gun, and rocket fire that seemed to come from every direction. Backed by air strikes, naval gunfire, and artillery support, the Marines inched forward. The fighting within the Citadel proved even more savage than the Marines had encountered in the battle for southern Hue. That night, Thompson requested continued artillery strikes to soften up the area for the next day’s assault.

At 8 am on February 14, the Marines renewed the attack, but made almost no headway against the entrenched Communist defenders. Not until the next day, after Company D, 1/5 was inserted into the fighting by boat, was the wall tower finally recaptured. Six more Marines were killed in action and more than 50 wounded. That night the NVA retook the tower for a short time, but D Company, commanded by Captain Myron Harrington, counterattacked and reclaimed it.

On the morning of February 16, Thompson’s Marines again advanced along the Citadel’s southeastern wall. From that point until February 22, the fighting seesawed back and forth while much of the Citadel was pounded to rubble by close air support and artillery. Bitter hand-to-hand fighting erupted on many occasions, the defenders occupying row after row of single-story, thick-walled masonry houses jammed close together and backed by solid walls riddled with spider holes and other fighting positions. M48 tanks and Ontos tracked vehicles found it extremely difficult to maneuver in the narrow streets and alleys of the Citadel. The Marines’ 90mm tank guns were ineffective against the concrete and stone buildings, their shells often ricocheting off the thick walls. The tank crews switched to concrete-piercing fused shells that resulted in excellent penetration. From that point, the tanks proved invaluable. The savage block-by-block fighting was reducing Hue to ruins. Many enemy troops killed or wounded by the Marines lay where they had fallen, trapped in the rubble of homes and courtyards, attracting rats and dogs. Because of health concerns, the Marines formed details to bury the enemy dead as rapidly as possible.

By February 17, the Marines of 1/5 had suffered 47 killed and 240 wounded in five days of fighting, the battle so intense that U.S. Navy medics and doctors had a difficult time keeping up with the casualties. The next day, his depleted battalion exhausted and almost out of ammunition, Thompson rested his troops in preparation for a renewal of the attack. The following morning, 1/5 began inching forward toward the Imperial Palace, paying dearly for every inch of ground taken.

While the Marines were fighting their way toward the palace, a South Vietnamese Marine task force entered the battle. Beginning at 9 am on February 14, these fresh troops launched their attack from an area south of the 1st ARVN Division headquarters, moving in a westerly direction. Ordered to make a turning movement to the left in order to take the southwest sector of the Citadel, they made little progress, encountering fierce enemy resistance as the two sides engaged in vicious house-to-house fighting. In two days, the South Vietnamese Marines advanced fewer than 500 yards. North of the Vietnamese Marine units, the 3rd ARVN Regiment, in the northwest sector of the Citadel, was having problems as well. On February 14, Communist forces broke out of the salient west of the Tay Loc airfield and cut off the 1st Battalion, 3rd ARVN Regiment in the Citadel’s western corner. It would take two days of bitter fighting for the ARVN to break the encirclement.

The Communist forces were having problems of their own. On the night of February 14, a U.S. Marine forward observer, working with ARVN units inside the Citadel and monitoring enemy radio frequencies, learned that the NVA was planning a battalion-sized attack through the west gate of the Citadel. He alertly called in fire from Marine 155mm howitzers and naval gunfire on preplanned targets around the west gate and the moat bridge leading to it, catching the NVA battalion coming across the moat bridge. A high-ranking NVA officer and a large number of reinforcements were killed. U.S. intelligence then learned that the NVA/VC were staging out of a base camp 12 miles west of the city and that reinforcements from that area were entering the Citadel using the west gate. Acting on this information, elements of the 1st Air Cavalry Division launched coordinated attacks on the city from their blocking positions to the west. On February 21, the 1st Cavalry troopers moved up and successfully sealed off the western wall of the fortress, depriving the defenders of incoming supplies and reinforcements and precipitating a rapid deterioration of the enemy’s strength inside the Citadel.

By February 22, the NVA held only the southwestern corner of the Citadel. A fresh U.S. Marine unit, Capt. John Niotis’s Company L, 1/5, was brought in for the final assault on the Imperial Palace. Leading his Marines along the wall and breaching the outer perimeter of the palace, Niotis and his men were hit by devastating fire from the remaining defenders. Niotis pulled his troops back for another assault. While the Marines prepared for their next assault on the imperial city, it was decided, in the name of political expediency, that a South Vietnamese unit should liberate the palace.

On the night of February 23-24 the 2nd Battalion, 3rd ARVN Regiment launched a surprise attack westward along the wall in the southeastern sector of the Citadel. The NVA were caught off guard but quickly recovered. A savage battle ensued, the South Vietnamese valiantly pressing their attack. Deprived of their supply centers to the west, the Communists were forced to pull back. Part of the ground gained by the South Vietnamese was the plot upon which the Citadel flagpole stood. At dawn on February 24, the South Vietnamese flag replaced the Vietcong banner that had flown over the city for 24 days. Later that day, after the 1st ARVN Division reached the outer walls of the Citadel and linked up with elements of the 1st Air Cavalry, the last Communist positions were rapidly overrun by the allied forces and abandoned by the Communists, who fled westward toward sanctuaries in the jungles of Laos.

Tactical Victory, Strategic Failure

On March 2, the battle for Hue, the longest sustained infantry battle of the war to that point, was officially declared over. Losses were high. In 26 days of fighting, the ARVN lost 384 men killed, more than 1,800 wounded, and 30 missing. The U.S. Marines suffered 147 dead and 857 wounded, while U.S. Army units lost 74 dead and 507 wounded. The allies claimed that over 5,000 Communists, whose total forces during the fighting within the city had risen to about 12,000 men, had been killed inside the city and another 3,000 killed in battles in the surrounding areas. Much of the once beautiful city lay in ruins; 40 percent of the city was destroyed and 116,000 civilians were left homeless.

The Tet offensive and its attendant attack on Khe Sanh was a staggering failure for the Communists. Of the 84,000 troops committed to Tet, nearly 58,000 had been killed. The Communists had expected the ARVN to crumble, but it had fought hard and well; nothing resembling a general uprising took place. But although the allies had won a great tactical victory, the Tet offensive turned the tide of the war in favor of the Communists. The offensive created a political crisis within the Johnson administration, which became increasingly unable to convince the American public that the Communists had suffered a devastating defeat. All the optimistic assessments made prior to the offensive by the Pentagon and the administration came under heavy criticism and ridicule. On March 31, Johnson stunned the American people by announcing that he would not run for reelection. Moreover, he was severely curtailing the bombing of North Vietnam and would pursue peace negotiations with the enemy, virtually admitting that the war had been lost.

Even the North Vietnamese admitted they had suffered a terrible defeat—more Communist soldiers died in 1968 than did American soldiers during 10 years of involvement. The Communist strategy of bringing local VC cadres into the streets resulted in an unmitigated disaster. Instead of sparking a countrywide insurrection, it ended up a bloodbath, virtually destroying the Vietcong infrastructure in the south and eliminating the VC as an effective fighting force.

The keys to the failure of the general uprising were easy to discern: Hanoi had underestimated the mobility and vastly superior firepower of the allied forces; Hanoi’s battle plan was too complex and difficult to coordinate; and instead of concentrating their forces on a few specific targets, they attacked everywhere, resulting in their forces being defeated piecemeal. After the catastrophe, NVA General Tran Van Tra stated bluntly: “We did not correctly evaluate the specific balance of forces between ourselves and the enemy, did not fully realize that our capabilities were limited, and set requirements that were beyond our actual strength.”

Hanoi, however, soon realized that its huge sacrifices had not been in vain. Tran Do gave some insight into how defeat was transformed into victory: “In all honesty, we didn’t achieve our main objective, which was to spur uprisings throughout the South. Still, we inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans and their puppets, and this was a big gain for us. As for making an impact in the United States, it had not been our intention—but it turned out to be a fortunate result.” Despite the overwhelming tactical victory achieved by the allies in Hue and on other battlefields throughout South Vietnam, in the end the Tet offensive proved a strategic defeat for the United States. Ironically, the overwhelming victory achieved by the allies in the Tet offensive marked the beginning of the end for the American presence in Indochina.

Be advised that there was a very small Navy unit that was located in Hue in off of Le Loi street on the edge of the Perfume River, Hue Ramp. That small Navy unit was nicked name the Hue Ramp Tramps. They were a small force but held the ramp during the Tet Offensive of Hue. To this day their is no mention of them in regard to the battle of Hue. I was there Vietnam Navy Combat Veteran.