By Russell Corder

They have been called “the other Navy,” the “Navy’s stepchildren,” and perhaps most fittingly, “the forgotten Navy.” Officially, however, they were the Naval Armed Guard or more simply the Armed Guard (AG). Often mistaken for members of the Merchant Marine, the Armed Guard was a special branch of the U.S. Navy assigned to defend merchant ships against enemy attack. Its history is one of the most dramatic of World War II, fraught with danger, suffering, heroism, and staggering casualty rates. Yet, as one veteran wrote, “The Armed Guard hasn’t had as much publicity as the average two-headed calf gets.”

Formed in World War I, when German U-boats first prowled the Atlantic, the Armed Guard proved its worth protecting merchant ships. From U.S. involvement in 1917 until the Great War ended, U-boats attacked 227 American merchant ships. The AG repulsed 191 of these attacks, with a loss of only 36 ships. Perhaps most remarkable, throughout the war not a single American troopship guarded by the AG was lost to U-boats. Even with this extraordinary record, when the war ended, so did the need to arm merchant ships; and the Navy deactivated the Armed Guard.

The Threat of the German U-Boat: Reactivating the Armed Guard

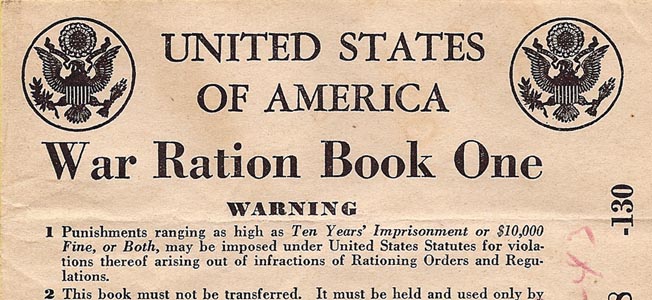

With Europe’s descent into war in 1939, U-boats again menaced the Atlantic. Although President Franklin Roosevelt promised to keep the United States out of the war, he decreed the country should be the “arsenal of democracy.” His decision to allow American merchant vessels to deliver war material to England meant these ships would be in harm’s way. This led to debates on how to best protect these ships. Some suggested arming merchant ships as a means for the mariners to defend themselves. Others feared that such an action might lead to more aggression by the Germans.

This debate was largely irrelevant since the Neutrality Act of 1939 made the arming of merchant ships illegal. Even so, the training of Navy gunners for service aboard merchant ships had already begun at naval armories, and on April 15, 1941, the Naval Armed Guard was officially reborn.

Increased U-boat activity from April through September 1941 gave President Roosevelt justification for the U.S. Navy to escort convoys. The U-boat attacks on the destroyers Greer and Kearny, the sinking of the destroyer Reuben James, combined with increased losses of American merchant ships led Congress to repeal Section 6 of the Neutrality Act that prevented arming merchant ships. With this legal hurdle removed, the Navy opened the first Armed Guard training center on September 17, 1941, at Little Creek, Virginia. Even though AG training had started in early 1941, Congress did not officially authorize the Armed Guard or the arming of merchant ships until November 1941.

While Roosevelt promised to keep America out of the European conflict, Navy gunners were being placed aboard American-owned merchant ships, including those under Panamanian registry. In the words of the chief of naval operations, Admiral Harold R. Stark, “The Navy is already in the war in the Atlantic, but the country doesn’t seem to realize it.”

“Sub Sighted, Glub, Glub”

After Pearl Harbor, the increased need for gunners aboard merchant ships resulted in the opening of additional AG training facilities at Gulfport, Mississippi, and San Diego, California. The camp at Little Creek, unable to handle the influx of new recruits, was relocated to larger Camp Shelton, Virginia.

For those recruits assigned to the AG, the first questions often asked were, “What the hell is the Armed Guard? Are they going to have us guarding a building or something?” A few knew the role of the AG, and they “wanted to go anyplace but the Armed Guard.” Those who did not know soon learned, and they would have agreed with AG veteran Robert Baxter’s assessment: “We were sitting ducks. We had a one-way ticket, and we weren’t going to be coming back.” Even their comrades in the fleet called those assigned to the AG “fish food.” One young ensign, it was said, shot himself after learning he had been assigned to the Armed Guard rather than accept condemnation to death. While the story was fictional, it illustrated the fear of serving in the Armed Guard.

The men in the Armed Guard knew the odds were against them, and many believed theirs was indeed a suicide mission. Representing this were two signs posted at a training center. The first declared, “Ready—Aim—Abandon ship!” The other, playing on the signal “Sub sighted, sank same,” read, “Sub sighted, glub, glub.”

In telling the history of the Armed Guard, one must not overlook the disappointment of the men upon receiving this assignment. A majority would have agreed with AG veteran Tracey Corder when he said, “I felt that the Navy had cheated me.” In the regular Navy, ships went hunting the enemy, and when the enemy was brought to bay, the two engaged each other in combat. These young gunners had dreamed of serving aboard warships, not on a slow “rust bucket” that ran from the enemy and let the escorts do the fighting.

Some may wonder why the merchant crews were not utilized as gunners. The Navy did attempt to train the mariners in the months before Pearl Harbor and set up gunnery instruction centers at major Atlantic ports, but few cared to take the training. From the Navy’s perspective, it was either use the AG or have no one trained to protect the ships. In defense of the merchant crews, it should be noted that most mariners learned to assist the gunners. Many became ammunition passers, and some learned to man the guns should the Navy crews become incapacitated. In the duel between the SS Stephen Hopkins and the German raider Stier, Cadet/Midshipman Edwin O’Hara singlehandedly manned the deck gun after the Navy crew was killed and fired the last five shots of the battle.

Training the Naval Armed Guard

Initially, training for the Armed Guard was limited and hampered by a lack of guns. At one gunnery school, there was a single outdated gun for every 500 men. Corder recalled that at Gulfport gunners were sent on an armed pleasure yacht to get a feel for the guns. Although they trained on the 3-inch deck gun and the 20mm rapid-fire guns, they did not get to shoot at targets until they were at sea.

Even officers’ training was lacking. One officer recalled his gunnery training amounted to an instructor pointing at two guns and saying, “This is a 4-inch gun and that is a 3-inch, and if you don’t believe it you can get a ruler and measure them.”

With the great need for experienced officers in the fleet, the sailors of the AG frequently had to make do. A man could be made a gunnery officer simply because he had some college and a little boating experience. Armed Guard veteran Zed Merrill noted that, if a seaman first class admitted experience with hunting weapons, he could find himself in charge of a gun crew. Although Navy regulations required that an ensign or lieutenant (j.g.) command the crew, it was not uncommon to have a chief gunner’s mate or a gunner’s mate in charge, especially early in the war or with a small AG contingent.

All that changed as the war progressed. Officers began receiving lengthy and advanced training. Lieutenant Robert Ruark of the U.S. Naval Reserve wrote in a wartime article for the Saturday Evening Post, “When the AG officer takes a ship today, his skull is bulging with fire control, gunnery, seamanship, communications, navigation, convoy procedure, aircraft identification, first aid, and simple surgery.“ Training for the gun crews also improved. While Corder received only five weeks of gunnery training in 1942, Bob Galati spent 18 weeks in gunnery school in 1943 with an additional five weeks of advanced school in Little Creek, Virginia.

Assigned to a Ship

After training, the new gunners were assigned to one of three Naval Armed Guard centers: Brooklyn, New York; New Orleans, Louisiana; or Treasure Island (San Francisco), California, where members of the AG would wait until assigned a ship. These centers were combination barracks, medical facilities, clothing depots, and schools for additional training. A man’s mail, records, and pay came through his assigned center.

If a sailor had been disappointed with his assignment to the Armed Guard, he was typically even more dissatisfied with his ship. Often the first ship assigned to a new Armed Guardsman was a rusted old freighter or tanker. Several wondered if their antiquated ships were even seaworthy. One AG officer remembered his first ship as “filthy dirty … the decks were caked with rust and most of the gear was rusty and tossed all over the decks.” A pile of garbage left on the deck was “beginning to crawl,” and the jumble of air hoses, fire lines, and electric cables made him feel as if he had “stepped into a junk yard full of serpents.”

Not all ships were in such disrepair. Another AG recalled his as being “designed for comfort, to bend and give with the tall waves, not to slam down and break her back against them.” Instead of being covered in rust, she had “fine rich wood in her paneling and pure bright brass fittings.” Although his ship showed signs of a hard life, “she carried herself with pride.”

Armed Guard personnel served on every type of merchant ship that sailed, from cargo ships, to tankers, to troop transports. One gun crew even found itself aboard a ship designed to haul mules. Besides tankers, the majority of AG personnel were assigned to the new Liberty ships. A Liberty was slow, averaging 11 knots, had no armor plating or graceful lines, but easily handled 7,176 tons of cargo in its holds, and more on deck. For all its shortcomings, the Liberty ships proved to be tough and durable, surviving tropical storms and Arctic gales.

By February 1942, Navy gunners could be found aboard American and Allied merchant ships as well as those of occupied nations. Ralph Dunwoodie, a signalman in the AG, served on Canadian and British ships in which he was the only American serviceman aboard. Because of the limited number of AG crews early in the war, however, American ships had first priority, followed by Panamanian, French, and British.

The AG’s Antiquated Weapons

In the beginning, the armament for merchant vessels was a hodgepodge of small-caliber machine guns and antiquated relics from previous conflicts. Some deck guns even dated back to the Spanish-American War. All ships carried machine guns, and for some that was the only defensive weaponry aboard. Early in the war many had only .30-caliber machine guns, weapons suited more for the battlefield than for combating aircraft and submarines. One gunnery officer recalled that the two .30-caliber machine guns aboard his ship still had tripods for field use.

Another gunnery officer described the first time his crew fired their old gun at an enemy submarine. No one knew if the sub was hit, for as soon as the gun was fired, “[We] were all too busy grappling with our own wreckage and testing our arms and legs for broken bones. The weapon’s thunderous concussion tore down stanchions, smashed the glass on the engine room telegraph dials, shattered a clock in the galley, blew radiator pipes from their fittings, broke shaving lotion bottles in five cabins, smashed 10 drinking glasses in the saloon, splintered the carpenter’s work bench, knocked out two door panels, ripped the door off the galley stove, and blew four pies out of the oven.”

Some ships even sailed without weapons. A few went to war with large poles protruding over the railings and painted to appear as guns. One ship lowered its booms along the deck to give the impression of possessing enormous cannons. As the war progressed and American industry gained a solid war footing, newer and better weapons were issued to the Armed Guard, such as .50-caliber machine guns, rapid-fire 20mm Oerlikons, and 5-inch dual purpose (surface and antiaircraft) deck guns. However, the shortage of adequate weapons was not solved until early 1945.

Regardless of the weapons aboard, AG personnel were trained to engage the enemy until “the decks are awash and the guns are going under.” Only after taking every opportunity to destroy the enemy could they abandon ship. Often they were the last to leave a sinking ship and they did so knowing that another convoy ship would not stop to pick them up, lest it too fall victim to the enemy.

27 Men Per Ship

The average Armed Guard detachment comprised 27 men, including six petty officers, a coxswain, two gunner’s mates, two signalmen, and a radio operator. On larger crews, a boatswain could also be included in the ranks. Armed Guard officers had the unenviable task of maintaining naval discipline, creating an effective gun crew, and establishing a working relationship with the ship’s master and merchant crew.

Unlike on the ships of the fleet, no medical personnel were assigned to the AG. Occasionally a pharmacist’s mate might be aboard, but most medical problems were taken care of by the AG officer and whatever remedies he could find in his medical chest. Should a serious medical problem arise, a doctor from an escort ship might be sent over. If that was not an option, the patient had to wait until his ship reached port.

Aboard ship, the merchant and Navy crews had separate sleeping and eating quarters. Part of the Navy crew had their quarters amidships, divided between port and starboard; the remainder had quarters on the stern. For those in the aft quarters, there was the constant vibration of the ship’s engine and propeller shaft with which to contend. In heavy seas, the stern would come out of the water and vibrate violently as the exposed prop chopped at the air.

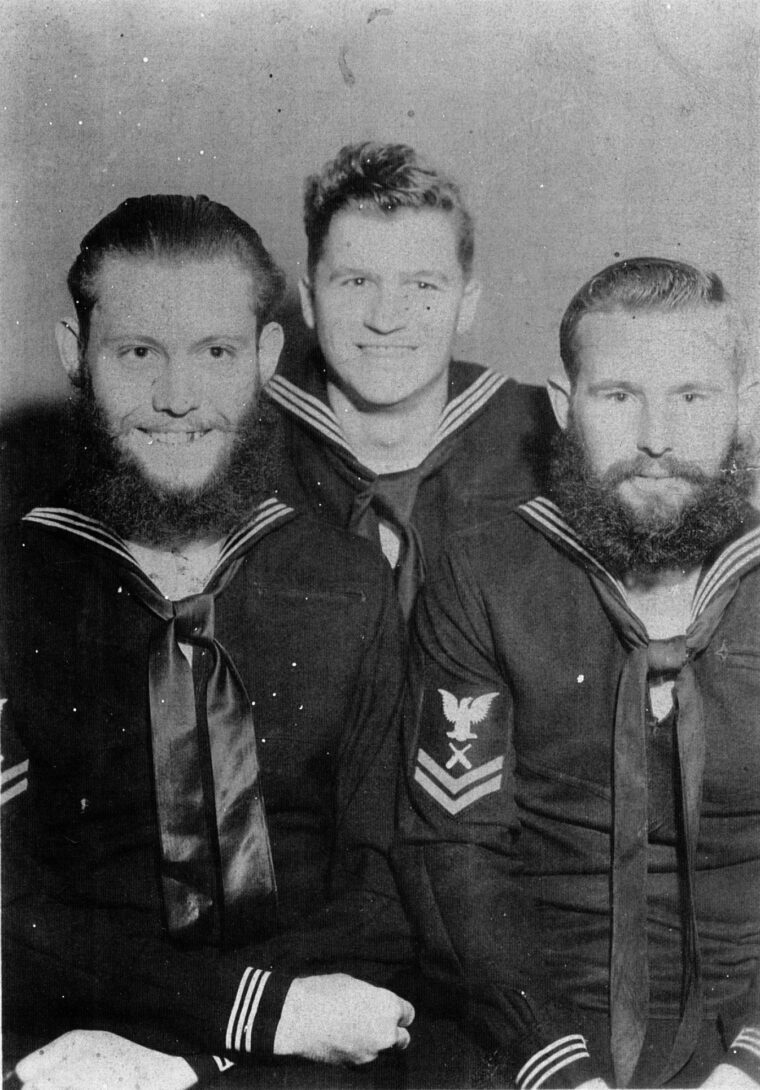

Armed Guardsmen did not always meet naval dress codes when they were at sea. Beards were common and, for those on long voyages, occasionally shaggy hair—at least by 1940s standards. The men learned that the best way to dress was not always the Navy way. Climate dictated what a man should wear to keep comfortable and alive. In warm waters, dungarees were the standard clothing, but it was common to see men in shorts, sandals, short-sleeve shirts, or even shirtless.

During the convoys to Russia, men dared not go outside without extra protection. Gunner’s Mate Roland Smith recalled that standard outerwear for the North Atlantic was a heavy fur- lined parka and fur-lined overall-type pants in addition to heavy gloves, an alpaca fleece-lined hat, face mask, and fur-lined goggles. Underneath, men would pile on whatever warm clothing they could find, including jackets, sweaters, wool pants, and thermal underwear. Howard Long remembered wearing special boots made from a type of rubberized canvas because the extreme cold caused leather boots to crack. Beneath these boots, men wore heavy felt bootees that came almost to the knees.

Threats from the Sea and the Air

Regardless of the climate, the AG was constantly on alert for submarines. Unfortunately, all too often the first indication the gun crew had of a submarine was the white phosphorus wake left by a torpedo as it plowed toward their ship. Even if the gunners did get a chance to fire on a sub, hitting it could be difficult. Usually the only target a submarine offered was a periscope, which, according to one AG veteran, looked like a post sticking out of the water. Hitting such a small target at long range was difficult. As long as the submarine stayed underwater, it had a distinct advantage over the guns of the AG. Should an overconfident submarine commander think he had an easy victim and attack on the surface, however, he quickly realized how efficient the AG gunners were.

While submarines posed the greatest threat to the Armed Guard, aircraft were a close second. Gunners were not overly concerned about enemy planes while far at sea, but closer to land the danger of air raids increased. Still, unlike subs, there was generally some type of warning of approaching aircraft, either visually or from the drone of the engines.

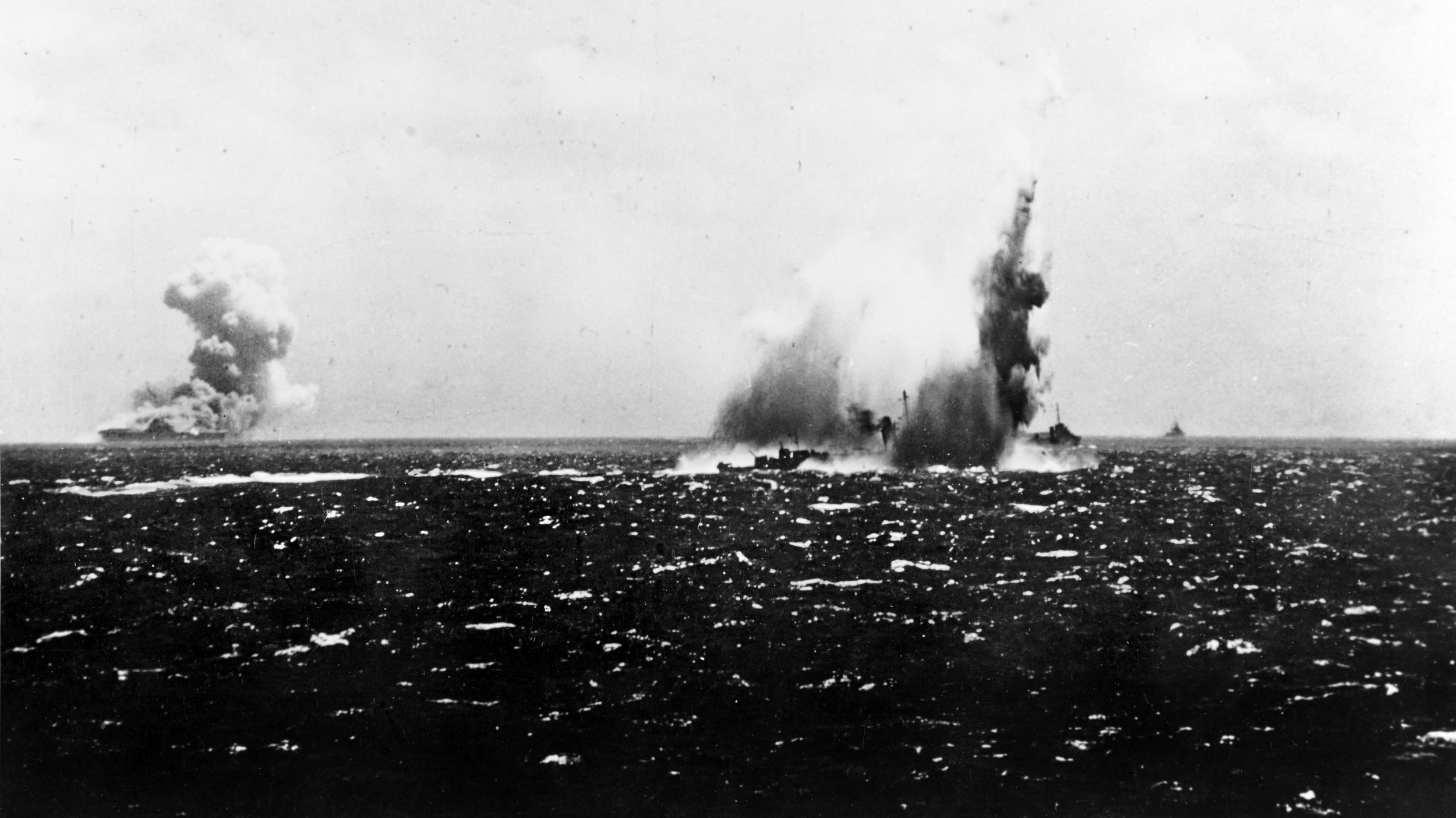

Should an enemy aircraft attempt to strike a convoy, it would have to fly through a wall of antiaircraft fire as the Armed Guard opened up with everything they had. As Lieutenant Ruark noted, “Sixty or eighty ships armed with Oerlikons and 3-inchers can toss up a screen of flack that a hummingbird couldn’t get through.”

Such a point is illustrated by an attack on convoy MKS-21, hit by some three dozen German planes near Almeria, Spain, on August 13, 1943. Although the Germans launched several torpedoes, only one found its mark. The AG gunners were more effective and downed an estimated 15 planes. German aircrews rescued from the sea complained about the intense antaircraft fire from the convoy and blamed it for their lack of success.

Armed Guard gunners in the Pacific also gave a good account of themselves. During the landings at Guadalcanal, the crew of the SS Nathaniel Currier successfully fought off an attack by Japanese planes. The ship’s master wrote to the commanding officer of the AG center at Treasure Island regarding the gunners’ actions: “It is my belief that the reason we sustained no casualties or damage was the volume and accuracy of the barrage put up [by the AG crew] … Seabee battalions in the Cactus-Ringbolt area repeatedly asserted that they had never seen a merchant ship put up such a volume of fire as this ship did.”

In the battle for the Philippines, the AG endured massive air raids in addition to repeated kamikaze attacks. At Leyte, over 120 merchant ships fought off repeated air assaults; five ships were lost and many damaged. Nevertheless, the Armed Guard was credited with the destruction of more than 120 Japanese aircraft. In statistical terms that meant for every ship lost 24 Japanese planes were shot down. Victory belonged to the AG at Leyte, but it cost 164 of their own.

Aside from submarines and aerial assaults, Armed Guard gunners also had to defend against surface attacks. Surface actions for the AG were not classic naval duels; rather they were defensive actions against hit-and-run raids by enemy torpedo boats or surfaced submarines. Additionally, there were the occasional surface raiders with which to contend. These ships, often disguised to look like neutral merchantmen, would unleash their deck guns, torpedoes, and in some cases torpedo boats against unsuspecting Allied merchant ships.

The number of merchant ships lost to these raiders can never be known for, as a postwar report stated, “Several ships went out independently and were never heard from again. They may have been torpedoed, suffered marine casualty, or [been] sunk by … armed surface raiders.”

The Deadly Voyage to Murmansk

For the men of the Armed Guard and the Merchant Marine, no voyage was as dreaded as the Murmansk run to Russia. Arctic storms, lack of escorts, continuous U-boat attacks and raids by German planes from Norway and Finland made the Murmansk run a horrific nightmare that drained a man mentally and physically. One AG veteran remembered, “It was light 20 hours a day … We were on the guns for 36 hours at one stretch, ate and slept right on the gun decks … One day nearly 100 planes hopped us….”

The slaughter of convoy PQ-17 in July 1942 is a classic example of what the AG faced trying to reach Russia. Starting on July 4 and lasting for several days, U-boats, torpedo planes, and bombers hammered the convoy almost incessantly. Although the ships fought valiantly, only three merchant ships were armed with 3-inch guns, the rest with .30- and .50-caliber machine guns. The Navy gunners remained at their stations for over 28 hours without relief and suffered from exhaustion. When the survivors of PQ-17 straggled into port, only seven of the original 33 had reached their destination.

On the Murmansk run, if the enemy was not trying to sink a man’s ship, then the weather was. One sailor remembered that while the North Atlantic could be beautiful, it could also “be the meanest, most treacherous old bitch on the face of the earth.” Another recalled gales that “shrieked down without warning as though they had been lying in wait for the chance to tear a ship apart.”

Veterans of the North Atlantic learned that ice could be as much a hazard as the enemy. Ice formed on the guns and had to be broken off with axes and picks. Howard Long recalled that while he was in Murmansk his ship’s guns froze, forcing the crew to take cover and wait out an air raid. William Schofield wrote of encountering a surfaced U-boat during a gale with freezing rain and sleet. The crews of both vessels raced for their guns as the range narrowed. Much to the shock of each crew, their guns were frozen solid with ice. In exasperation, the two crews simply stared at one another until they drifted from sight.

The Naval Armed Guard Remembered: “We Aim to Deliver!”

Despite their contributions to the war effort and the heroism in combating the enemy and the elements, some writers have disparaged the men of the AG. According to one account, they had “minimal education” and were assigned to the AG because they could not “qualify for anything else.” It was as if they could never be real sailors. The only thing not real was the description. Many went on to become successful businessmen and public servants. One became a governor, another a state supreme court judge, and one gunner transferred to the Army and rose to the rank of general.

During the war, the fleet often sought out AG gunners for their ability to accurately judge distance and speed of a target simply by eyeballing it. Yet, regardless of the initial shock at being assigned to the AG, the hazards, and the lack of glory, most did not want to leave the Armed Guard. Some gunner’s mates did not try for a higher rating because it might require transferring to the fleet. The majority of Armed Guardsmen would probably agree with Tracey Corder when he said, “I guess I developed an affinity for those old rust buckets.”

By the end of the war, 1,810 Armed Guardsmen had given their lives in the line of duty. They met the enemy “oftener [sic] and on more widely divergent fronts than any other branch of our fighting forces,” commented one observer. Some died quick deaths when their ships exploded from torpedoes or bombs. Many burned to death in the inferno of a blazing tanker. Others died slow deaths in lifeboats or on rafts in the freezing waters of the North Atlantic or under the blazing tropical sun.

The motto of the Naval Armed Guard was “We Aim to Deliver!” In the end, they more than lived up to it. For their valiant service, the AG received 8,033 decorations or commendations. Armed Guardsmen also received commendations from the governments of Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Five destroyer escorts, one destroyer. and a transport were posthumously named for Armed Guardsmen. Today at Armed Guard reunions, their motto can still be seen, but with the proudly added boast, “We Delivered!”

First-time contributor Russell Corder is a former university professor and resides in Pleasanton, Kansas.

I absolutely loved reading this and learned soo much!

My grandfather served on the merchant ships as a first gunner’s mate armed guard…

You mentioned there was a few ships that had fake guns… my grandfather told stories of the dread and fear he felt when he discovered he’d have to make that trip twice an a boat with fancy fake guns…. “We could point our ‘guns’ at them all we wanted, even had all the ammunition we could ever need, and couldn’t actually fire a damn thing…. We relied on the fear and gullibility of the enemy, and we prayed they fell for it.”

Anyway, Thankyou for a great and educational read!!

Kindly,

Mandi Pyke

Oct 23, 2021

I believe the sailor in the last photo could be my father. He was in the AG in the Pacific. He served from 1943 to 1946. Is there any way to find out more about that photo?

“The men in the Armed Guard knew the odds were against them, and many believed theirs was indeed a suicide mission…”

No good deed goes unpunished.