By John Brown

Hours after Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japanese troops landed in northern Malaya and began moving south toward Singapore.

In Singapore, Captain Ivan Lyon of the Gordon Highlanders, an intelligence officer at British Army headquarters, was ordered to the Dutch East Indies island of Sumatra to organize a route across the island that could be used by the military, the idea being that if “impregnable” Singapore came under prolonged siege by the Japanese, troops from India could be landed on the west coast of Sumatra at Padang and take the route laid out by Lyon to the east coast where they would be close to Singapore to mount relief operations. In the event, however, Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942, and refugees escaping from Malaya and Singapore used the route in the reverse direction across the island.

Operation Jaywick: Planning the Raid on Singapore

Bill Reynolds was an Australian who had served aboard destroyers in World War I and had lived in Burma, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies for the past 20 years. Nearly 50 years old, he volunteered his services at British naval headquarters in Singapore and was given command of the Kofuku Maru, a narrow-gutted 70-foot-long Japanese fishing boat seized by the British when the war began. He found half a dozen Chinese willing to crew her and began picking up refugees—British, Chinese, Malays and others—from the islands around Singapore where they had been stranded when the ships in which they had been attempting to escape had been bombed and strafed by Japanese aircraft.

He crammed 50 or more into the Kofuku Maru and, sometimes towing disabled craft filled with refugees, ferried them to Sumatra. It was there that he met Ivan Lyon, and it was there that Lyon first got the idea of raiding Singapore. Listening to Reynolds, who had been operating the Kofuku Maru around Singapore for two weeks during which he had rescued some 1500 people, he probably asked himself why could not he, Lyon, go back into Singapore waters on a mission designed to cause trouble for the Japanese?

In early March, with Malaya and Singapore in Japanese hands, with the Dutch East Indies invaded, and Japanese troops closing in, Lyon crossed the island of Sumatra, commandeered a native fishing prahu and, with 15 Europeans, one Chinese, and one Malay on board, raised the rotting sail and took off into the Indian Ocean with only a prismatic compass, a page torn from a nautical manual, and his wrist watch to navigate by. But he was an experienced small boat sailor and, surviving strafing by Japanese planes, storms, periods of dead calm, and searing heat, he reached Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) 1,700 miles and 52 days later.

Subsequently, in Delhi, India, Lyon learned that Bill Reynolds had sailed the Kofuku Maru all the way to India and was now in Bombay. It was then that the idea that had been simmering in his mind crystallized—use the Kofuku Maru, a Japanese fishing boat indistinguishable from hundreds of others in use in Asian waters, to raid Japanese ships and installations in Singapore harbor.

He sketched out a plan and took it to the SOE (Special Operations Executive) India Mission where it was approved. But because of poor security in India and Japanese vigilance in the Indian Ocean approaches to Singapore, SOE asked Australia’s clandestine operations unit SRD (Services Reconnaissance Department) to undertake the training, manning, equipping and dispatch of the expedition from Australia.

Lyon renamed the Kofuku Maru the Krait after the six-inch-long Asian snake with nerve-paralyzing venom that can kill in minutes and codenamed the operation Jaywick after the powerful deodorant Jay Wick used extensively in Malaya and Singapore.

The Fate of Bill Reynolds

Bill Reynolds tried twice to sail the Krait to Australia, but each time her old engine broke down and she was finally shipped to Sydney as deck cargo on a freighter. By then Lyon, now Major Lyon, had selected his team and they were undergoing intensive training near Sydney in canoeing and night navigation and movement on sea and land, sharpening their skill with a variety of weapons and explosives and in unarmed combat. After three months the team moved north to the ZES (Z Experimental Station) near Cairns on Queensland’s far north coast to wait for the Krait while continuing their vigorous training.

After numerous breakdowns the Krait was towed to Townsville, south of Cairns, her engine completely useless. There Bill Reynolds left her. A 51-year-old civilian, he went to Melbourne, Victoria, where he joined the clandestine civilian Bureau of Economic Warfare. Fluent in Malay and with a good grasp of Chinese, he was landed by the American submarine Tuna in the Straits of Macassar to pick up information from Chinese secret agents but was betrayed to the Japanese by local people. After months in the notorious Surabaya prison on Java he was sentenced to be executed. The tall, lanky Reynolds refused to kneel for beheading by the executioner’s sword and the small, perplexed executioner had to call on some soldiers to form a firing squad.

Assembling the Raiding Team

Lyon located a replacement engine for the Krait in Hobart, Tasmania, and had it shipped to Townsville and installed. For simplicity’s sake and to save space, he scrapped the part of his plan to destroy harbor installations in Singapore and concentrated on shipping. Even so, when the 70-foot-by-11-foot Krait sailed to Cairns and was fitted out with supplies and stores for six months. With diesel fuel, kerosene, canoes, weapons, explosives, equipment, spare parts, and radio gear, there was only enough space left for the team to sleep a few at a time in hammocks slung in any vacant spot.

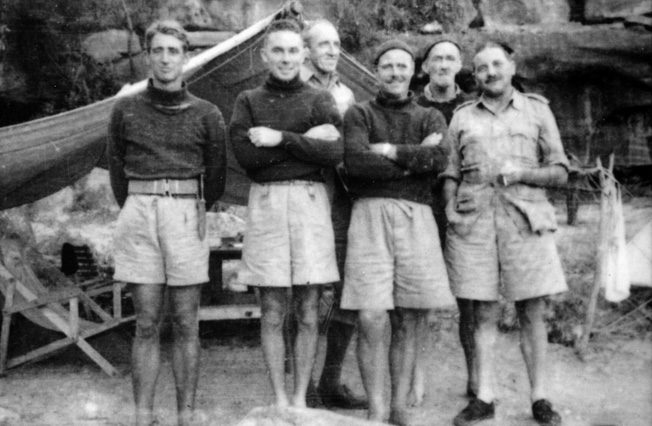

Lyon’s team included Donald Davidson, second-in-command, British Royal Navy, a tough, resourceful Englishman who had spent years in Australia’s outback and the jungles of Southeast Asia and had been commissioned in the Navy in Singapore with no previous naval experience; Lieutenant Bob Page, Australian Army, former third-year medical student who had swapped university studies for special operations; Lieutenant Ted Carse, Australian Navy, navigator, who had sworn off alcohol for this operation; Stoker Paddy McDowell, British Royal Navy, ship’s engineer and World War I veteran; Corporal Taffy Morris, a British Army medic who had escaped from Sumatra with Lyon; Corporal Andrew Crilley, an Australian Army engineer who had volunteered to be cook to get selected for the team; Telegraphist Horrie Young, Australian Navy; and six young Australian Navy seamen who had not yet been to sea—Wally Falls, Freddie Marsh, Cobber Cain, Andrew Huston, Arthur Jones, and Mostyn Berryman. All were volunteers from the Z Special Unit, usually called Z Force.

On August 9, 1943, they left Cairns on a 2,400-mile voyage around the north of Australia to Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia. There the crew of the American submarine repair ship Chanticleer did some excellent repair work on the Krait while refusing to believe that the “crate” had made it all the way from Cairns. They prepared her with 150 pounds of plastic explosives so that she could easily be blown up if captured.

“It is Singapore Harbor”

On September 2, the Krait left Exmouth Gulf heading north into a vicious, unexpected storm. Vastly overloaded and unwieldy in open ocean, she was continually washed over. Great waves threatened to sink her, and a hole had to be chopped in her side to release the huge amount of sea she took aboard. On the second day, the storm abated and Lyon called the team together and told them their objective, ending long speculation.

“It is Singapore harbor,” he said, and his announcement brought only one disappointed comment.

“I thought it would be Tokyo. If I’d known it wasn’t, I wouldn’t have come,” said one crewman.

Lyon briefed the team members on the operation. The Krait would drop a six-man attack team on one of the islands as close as possible to Singapore harbor from where they would make the attack in three canoes while the Krait hid among the islands and come back to pick them up after the operation. He named the six men who would carry out the attack, ignored the protestations and curses of the ones who would have to remain on the Krait, and laid down the rules. The Japanese flag would be flown at all times; as they hoped to pass as local fishermen their faces and bodies would be stained brown, and Malay-style sarongs would be worn; no garbage would be thrown over the side that might identify them if it was found; no lights at night.

“Thank Christ We Are Just Through Lombok”

On September 8, the raiders were more than 700 miles north of Australia and within sight of Gunung Agung, the 10,000-foot sacred mountain of Bali, and the equally sacred 12,000-foot Gunung Rinjani on the nearby island of Lombok. That night they steered between the two islands into the 25-mile-long Lombok Strait, hoping their fishing boat flying the Japanese flag would not be challenged and to make it through by dawn. But they quickly encountered a problem.

The strait was a maze of extremely strong currents and rip tides. They were so strong that at one time during the night the raiders did not advance at all for two hours as the Krait battled a current as fast as her own speed of eight knots. In six hours, she made half a mile before the tide changed and the currents ran with them. When dawn broke they were still in the middle of the strait with the coast of Bali on one side and the tents and huts of a Japanese military camp on an island on the other.

However, they were not challenged and by 10 that morning navigator Ted Carse was able to write in his log: “Thank Christ we are just through Lombok….” They were now in the Java Sea.

Keeping away from sea lanes and among islands and shoals, they sighted only a two-masted Macassar proa and a Japanese plane on their first day in the Java Sea. On the second they heard on the radio that Italy had surrendered and toasted the news with mugs of cocoa. During the night they were close to the coast of Borneo, and the next day swarms of butterflies followed them for miles. They began to see more and more fishing craft and trading vessels as they continued on into the China Sea.

In the “Thousand Islands” that led to Singapore, Lyon decided that the Krait should not wait among the islands while the attack took place in the harbor since it would be difficult to hide among them during the search that would inevitably follow the attack. The Krait would cruise the Borneo coast and come back to collect the attack team after the operation.

Finding an Ideal Pickup Point

On the night of September 16, the raiders anchored off a beach on the island of Pompong, and Davidson, Cain, and Jones went ashore and buried cans of water and emergency supplies. During the night they listened to the growl of engines as Japanese seaplanes were warmed up at the base on nearby Chempa Island and watched searchlight beams in the sky.

The following day they searched for a suitable island from which the attack could be launched. Several times they jumped to action stations when Japanese motorboats came close and once sweated it out as they passed within clear sight of a Japanese observation post. Finally, Lyon decided on one of the islands they had seen earlier, and they turned back to it, the lights of Singapore in the sky behind them.

In blustery winds and rough seas they anchored off a beach on Pandjang Island and stacked the gear for the attack team on deck. The sound of the powerful engine of a patrol boat came from close by in the darkness, and they waited in silence until it faded away. It returned, but farther off. An hour after midnight the wind died down, and they were able to launch the dinghy. Davidson and Jones rowed ashore and searched the island for signs of habitation but could not find any.

The gear was taken ashore—canoes, limpet mines, food and water, arms and ammunition, clothing, medical kits, and a bag of Dutch gold guilders. The Japanese patrol boat, whose engine they had heard earlier, again passed very close.

Lyon called a meeting of the team. It was decided that this island, Pandjang, 30 miles from Singapore, was too close as a pickup point after the raid, that 12 days should be allowed for the raid, and that the attack team should be picked up at Pompong Island—50 miles from Singapore—where they had buried the emergency rations. Pickup would be at midnight on October 1. If the attack team was not there, the Krait would return 48 hours later.

A Close Call With a Japanese Sampan

At 4 am, the attack team—Major Lyon, Lieutenants Davidson and Page, and Seamen Falls, Jones and Huston—shook hands with the others and were rowed ashore.

The Krait up-anchored and moved away in the darkness to cruise aimlessly along the coast of Borneo and in the China Sea for two boring weeks, the crew passing the time as best they could, impatiently waiting out the long days and nights until they could sail for the rendezvous.

On Panjang Island the attack team found they had rubbery legs after having been cooped up on the Krait for so long. They dragged the gear inland and hid it and spent the next two days exercising, always with one on guard to warn when planes came close or ships or boats were passing the island. After dark on the second night, they carried the canoes and gear back to the beach.

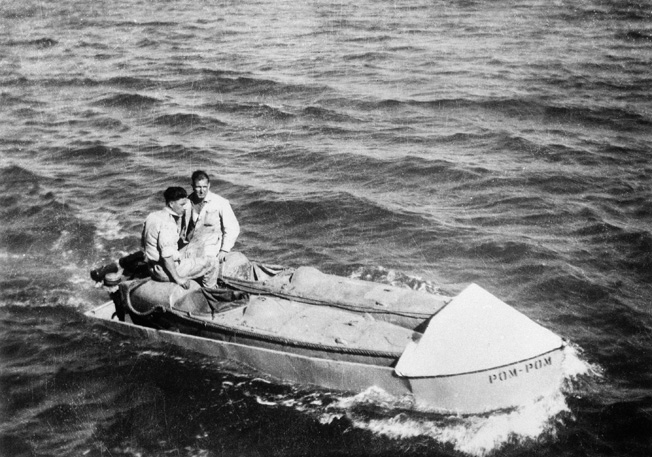

The canoes were 17 feet long and, loaded with two men, limpet mines, arms, equipment, food and water, weighed almost a third of a ton. They got them into the sea and waited, each man dressed in a black Japara silk suit and black exercise shoes, faces and hands blackened, pistols and knives strapped on, compasses and first aid kits in zippered pockets, each with a cyanide tablet within easy reach in case of need. When the regular Japanese patrol boat passed, they climbed into the canoes and began paddling toward Singapore, Lyon and Huston in one, Davidson and Falls in another, and Page and Jones in the third.

They paddled until midnight, covering 11 miles, and then, tired and sore from the unaccustomed labor, pulled in at the small, uninhabited island of Bulat. They unloaded the canoes and carried their gear to a grove of palms in the scrub and lay down and slept until daylight.

Waking, they looked out to sea to find a motorized sampan flying a Japanese flag moving slowly toward the beach, and on the beach there was still some of their gear. Two of the canoes were only partly hidden. Pistols ready, cursing themselves for their carelessness, they watched the sampan anchor just off the beach. During the next hour they held their breath as Japanese sailors moved around on the deck of the sampan, but none of them noticed the gear on the beach. When the sampan left, they quickly got the gear and canoes under cover.

Passing Through the Bulan Strait

After dark, still stiff and sore from the previous night’s paddling in the cramped canoes, they set off for the Bulan Strait. The strait was only a mile wide, and the rip tides and whirls among the islands made paddling the heavily laden canoes extremely difficult. They had traveled less than nine miles when they dragged the canoes among the mangroves of Bulan Island just before dawn. When dawn broke, they heard voices calling and could see people moving about in a village only a short distance away on the next island. Looking around, they saw more villages dotting other small islands, and sailboats and canoes began using a channel only yards away from them.

They laced mangrove branches as camouflage, ate some of their rations, and lay down in the stinking mangrove mud to sleep, their calm broken by calls coming from the villages, dog fights, and the shouts of boatmen passing so close that the sails of their boats blotted out the sun. It was a miserable day. Sandflies attacked them in swarms, and crabs nipped them as they lay baking in the sun, but in the late afternoon it rained heavily and, refreshed somewhat by it, they left in their canoes as soon as it was dark.

They were out of the Bulan Strait by midnight and by 2 am could see the lights of Singapore in the sky—they were too low in the water to see them directly. They landed on Dongas Island and hid their canoes and gear. They were eight miles from their target and 2,000 miles from their base at Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia.

The next morning they checked the island and found it uninhabited. From a high point, using a telescope, they spent hours looking through the haze into the harbor. For Huston, Falls, and Jones, Singapore was just another island, an island to be attacked, but for the other three there were emotional links. Bob Page’s father was a prisoner in Singapore as were Donald Davidson’s brothers, and for Ivan Lyon it was his wife and young son. They had escaped Singapore before its fall and reached Ceylon. Sailing to Australia to join Lyon, their ship was sunk in the Indian Ocean and they were taken as prisoners to Singapore. Lyon knew that much but did not know they had been moved to a prison camp in Japan. They survived in the camp until freed by American troops when Japan surrendered.

A Target Too Good to Miss

The attack team rested on Dongas Island for much of the next two days and watched the courses steered by a variety of ships for evidence of minefields. They could not detect any. There seemed to be no regular air or sea patrols or port security measures, and at night there was no blackout of Singapore city. The Japanese were taking few precautions; they were obviously very sure of themselves.

On the second afternoon, a convoy of 13 ships moved into the Roads, preparatory to leaving the harbor. It was too good a target to miss, and after dark the team carried their canoes to the beach and launched them.

At midnight they were still two miles from the Roads, fighting a crosstide, when a searchlight snapped on. Motionless, they floated for half a minute in the glare, expecting an alarm to sound, and then the light went out. They closed up and decided that, because of the crosstide, they would have to give up for the night. They also decided they would find another island from which to launch their attack.

They left Dongas Island the next night and, fighting the tides between islands, they reached Subar Island, seven miles west of Dongas, just before dawn.

Subar was a rocky island, the rocks too hot to touch, and so hot it was impossible to sleep during the day. The men lay on blankets on a cliff top where they could look down on the sea 60 feet below and watch the passing parade of junks and ketches, proas and sampans. The heat haze lifted in mid-afternoon, and through the telescope they examined the harbor, transferring what they saw to their chart and planning their attack that night.

Under a moonless sky they paddled for the lights of Singapore. In the harbor they twice lay forward and motionless in their canoes while searchlights played over them, but no alarm was raised. Then they separated, looking for targets.

“A Good Night’s Work”

Along Bukum wharves where the sea glowed with reflected light, Bob Page and Arthur Jones passed a 5,000-ton freighter, then a small coastal ship and a big, well-lit tanker on which welders were working. Page decided on the freighter. They had to cross a large patch of full light before they came into the shadow of the freighter, and when their eyes adjusted they moved along its hull attaching limpet mines below the waterline, timed to explode at 5 am.

They hung on the anchor chain, resting and eating chocolate bars and listening to the chatter of the welders and other workmen on the tanker until, warned by instinct, they looked up to see a uniformed Japanese guard on the deck above them. Unmoving, they watched him for several minutes until he spat into the sea beside them and moved on. They paddled away.

Their second target was a large, modern ship low in the water with cargo. The glow of its lights on the water around it and the red dots of cigarettes being smoked by the crew on deck made it a dangerous target, but they took the risk and attached limpets. Leaving this ship, they were caught in a rip current that, before they realized what was happening, bumped the canoe against the rudder of a heavily laden tramp steamer. They attached their remaining limpets to it and, bathed in sweat and desperately tired, they began paddling for Dongas Island where they would meet the others.

Ivan Lyon and Andrew Huston paddled into Examination Anchorage where, in contrast to the lights that had plagued Page and Jones, there was almost complete darkness. Low in the water, it was almost impossible for them to spot ships against the blackness of the anchorage and the shoreline hills. They paddled for two hours unable to find a ship and then saw a red light and the silhouette of a tanker. They circled her, noting how low she was in the water and, knowing that it was difficult to sink a tanker with limpets, they decided to put all they had on her.

As they could hear voices on deck, they worked slowly and cautiously. They placed three limpets over her engine room, another three around her propeller, and moved along her starboard side. With two more limpets attached and the last one ready to go on, Lyon looked up to see, 10 feet above him, a man’s head out of a porthole, his face pale against the black hull. The man sniffed and cleared his throat, and Lyon, the limpet in his hands, wondered if he would have time to attach it. So he set a one-minute fuse to detonate it if they were challenged. The head disappeared, a light appeared in the porthole, and they waited for the man to return with a flashlight to shine on them. He did not. Lyon attached the limpet, and they paddled away.

Donald Davidson and Wally Falls paddled into Keppel Harbor, where they were almost run down by a steam ferry. Passing the yacht club, they could hear Japanese voices raised in song and other sounds of party revelry. In Empire Dock, where there were ships, it was so highly floodlit and there was so much activity going on they kept moving, following an ocean-going tug into the Roads off the business heart of Singapore. Here there were plenty of ships and a lot of light.

They drifted in beside a heavily laden freighter and attached three limpets, then moved on and did the same to a second freighter and a third. The Victoria Hall clock chimed 1 am. It was getting late. They decided not to return to Dongas Island but to make straight for the rendezvous on Pompong Island.

Lyon, Huston, Page, and Jones reached Dongas just before daylight, and after nine hours in the canoes they were so exhausted and sore they had great difficulty unloading and hiding the canoes. But they scrambled up the hill and waited expectantly in the growing daylight. At 5:15 they heard a dull explosion—and six minutes later a second one. They could hear the sound of sirens. In the next 20 minutes they heard five more explosions. “A good night’s work,” Jones said.

Returning to the Krait

With full daylight they could see through the telescope that ships were dispersing in the harbor and watched smoke billowing from the burning tanker. Sirens wailed continuously. Then they saw the planes. The hunt for them was on.

Naval patrol boats and fast sampans joined the planes. With one on guard the others tried to sleep, but exhausted as they were they could only doze and wake to the sound of engines above and close by them. That evening a naval patrol boat passed slowly only 50 yards off the beach while officers examined the island through binoculars. When the patrol boat moved on and as soon as it was dark, they launched the canoes and left the island.

Patrolling Japanese boats and storms delayed them and they reached Pompong Island at 3 am on October 2. The Krait was not there. They crawled and staggered up the beach, hid the canoes and gear, and collapsed.

The Krait had returned to Pompong Island for the rendezvous. The crew had heard no news on the radio about the raid and were unaware as to the fate of the attack team. With the possibility that the team had been captured and an ambush was waiting at Pompong, the crew had their weapons cocked as the Krait moved slowly to the landing beach and the anchor was dropped. It was 12.30 am—they were half an hour late. They saw a movement on the beach, and Davidson called to them. Minutes later he and Falls were on board.

They waited until dawn and then left, watched by Lyon, Page, Huston, and Jones from another beach. In their exhaustion and the dark, they had waited on the wrong beach. They moved to the right beach and waited for the Krait to return two nights later. She arrived exactly on time at midnight.

Except for one tense occasion when a Japanese destroyer passed them 100 yards away for eight minutes while officers examined the Krait through binoculars from the bridge, the voyage back to Western Australia was relatively uneventful. On October 19, they anchored in Exmouth Gulf, 47 days and 5,000 miles after heading north for Singapore, with 33 of those days very definitely in Japanese waters.

Operation Rimau: A Second Raid on Singapore

Although the loss of Japanese shipping in the operation, 37,000 tons, was very small in comparison with, say, Japanese ships sunk by American submarines, the sheer daring of the operation would have given a boost to Allied morale if it had been publicized and would probably have created panic in every Japanese occupied port in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. But the operation was classified top secret as knowledge of it by the Japanese could jeopardize any future similar operations. The story of operation Jaywick was buried in the files until long after the war.

The Jaywick team returned to Z Force, not knowing that in Singapore the Japanese had blamed local saboteurs for the sinking of their ships and begun an investigation that led to the imprisonment, torture and execution of hundreds of Chinese and Malays, and some of the Europeans interned on the island.

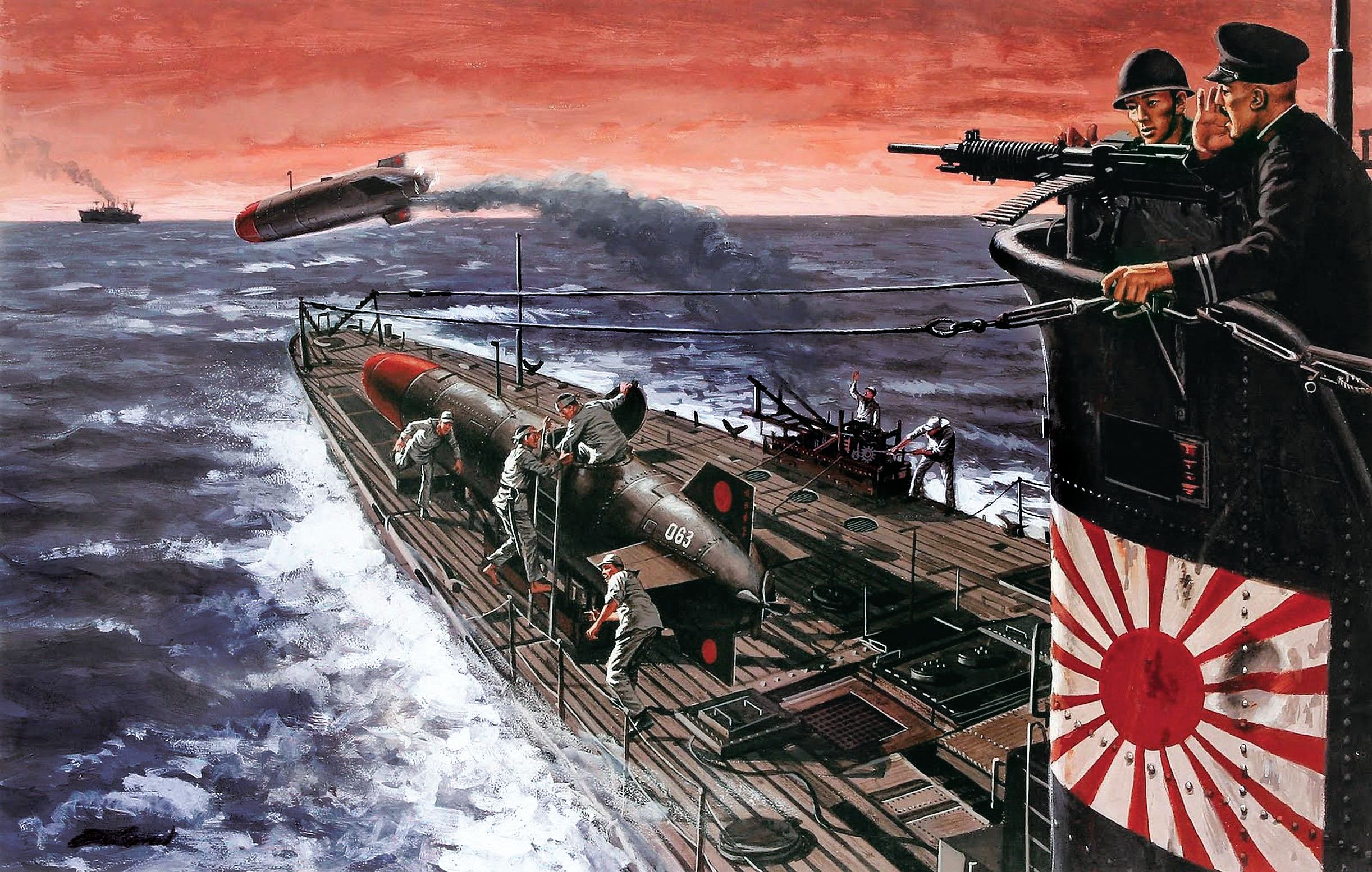

Ivan Lyon, now a lieutenant colonel, believing that the Japanese would not expect another attack on Singapore, proposed a second, larger attack. British Special Operations approved it, and Lyon went to England to check on all the latest materials and equipment. There he examined a large minelaying submarine, the Porpoise, and tried out a Sleeping Beauty (SB), a 13-foot craft that could carry a man at four and one-half knots on the surface of the water or three and one-half knots underwater and had a range of 12 miles on a fully charged battery. The minelaying submarine and SBs were just what he wanted.

He returned to Australia, and at Careening Bay near Fremantle in Western Australia he began selecting and training volunteers for the operation he codenamed Rimau, the Malay word for tiger.

He decided to use four of the men who had been on the Jaywick operation, Davidson, Page, Falls and Huston, and 17 other British and Australian sailors and commandos. Major Reginald Ingleton of the British Royal Marines would go with them as an observer, but he quickly joined in as one of the team.

Mission Aborted

On September 11, 1944, the minelaying submarine Porpoise left Careening Bay crammed with 15 SBs, 11 folboats (special operations canoes), 15 tons of supplies, arms, limpet mines, radio and other equipment, and Lyon and his 22-man team. Off the coast of Borneo a two-masted junk named Mustika was captured and sailed to the island of Pedjantan, where the team’s equipment and supplies were transferred to it. The Porpoise, with the crew of the Mustika aboard, returned to Australia promising to come back for the team in 40 days.

Nothing more was heard of Operation Rimau until after the war when Services Reconnaissance Department files were opened to researchers and their contents linked with information from other sources and reports of the interrogation of Japanese officers, the Kempei Tai, and local people of Singapore and the islands.

After leaving the Porpoise, Lyon and his team sailed the Mustika into the Thousand Islands, looking for a suitable base from which to launch their attack. Late one afternoon, in the lull before rain began and with the Mustika’s sails hanging limp, they drifted past the small island of Kasu. Unexpectedly they came upon a fishing village, a few houses on piles sunk in the sand and mud. As they drifted closer a motor launch came toward them. In it were half a dozen Water Police, Malays who wore Japanese uniforms and were controlled by the Kempei Tai.

Closer, it was obvious to the Malays that the men on the Mustika were Europeans even though their bodies were stained brown and they were wearing sarongs and straw coolie hats. One of the team opened fire on them, killing them all except one who dived over the side and swam back to the village. The incident took place within sight of the people of the village.

Knowing that armed Japanese ships and planes would soon be on the scene, Lyon had no alternative but to abort the operation. He ordered 12 of the team away in six of the folboats and with the others sailed the Mustika into deeper water where they launched folboats and a folding boat filled with equipment and blew up the Mustika and the SBs.

Lyon’s Team Wiped Out

Although the team was primarily concerned with escape, there is evidence that Lyon and some of the men paddled into the Roads outside Singapore harbor and attached limpets to some ships. There were several explosions that night, and three ships were sunk. Believing it was the work of local resistance fighters, the Japanese retaliated, and severed heads of Chinese and Malays soon appeared on spikes around the port city. It was only when news of the incident at Kasu reached Kempei Tai headquarters that the hunt for the Rimau team began, and by then they were scattered among the islands. They were hunted for weeks.

In a clash with Japanese soldiers on Soreh Island, Donald Davidson and Archie Campbell were both badly wounded. When the Japanese pulled back waiting for reinforcements, the two wounded men were given shots of morphine and put in a folboat. They paddled toward Tapai Island while Lyon and two others stayed behind to hold off the Japanese and give them a good start.

More than a hundred reinforcements arrived, and Lyon, Lieutenant Bobbie Ross, and Corporal Clair Stewart held them off for most of the night with Sten guns and grenades, killing 44 and wounding 20. Toward dawn, Lyon and then Ross were killed. Stewart, wounded, evaded the Japanese but was later captured. He was tortured but refused to say anything about the operation. Davidson and Campbell reached Tapai Island where, in agony from their wounds and unable to go any farther, they swallowed cyanide tablets.

Others of the team were killed, died of wounds or were captured, some after incredible feats of endurance. Two were captured on Java where one of them died after being inoculated with drugs in a medical experiment carried out by Japanese doctors. Two others, Australian commandos Warrant Officer Jeffrey Willersdorf and Corporal Hugo Pace, sailed a small fishing kolek from island to island 2,000 miles along the coasts of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok, and Flores to Romang Island near Timor where they were betrayed to the Japanese. They were taken to Timor, where they died of torture, starvation, and disease.

10 Prisoners Executed

In all, 10 of the team were brought as prisoners to Singapore. The Japanese considered them warriors in the spirit of Bushido, who had fought and had been captured, not surrendered. They treated them with respect. They were questioned repeatedly but not badly treated even thought they refused to tell anything of real importance about the operation.

At the end of May 1945, a new Japanese commander in Singapore ordered that they be court-martialed. The court martial was held in early July, apparently against strong opposition by many in the Japanese military. The team was accused of being involved in a covert operation, not wearing full military uniform, and displaying the Japanese flag to confuse their enemies. They were found guilty and sentenced to death.

On July 7, they were taken to a hill outside Singapore where they talked, smoked last cigarettes, and shook hands with one another. They were then ceremonially executed by the sword in the warrior tradition, their bodies falling into the graves prepared for them.

After the war, the bodies of the 10 were exhumed and, together with the bodies of those who died on the islands near Singapore, including Ivan Lyon, were buried in the Kranji war cemetery on Singapore Island.

In 1957, Z Force veterans found the Krait, virtually a hulk, hauling timber on the Borneo coast. She was brought back to Australia, restored, and now sits in the National Maritime Museum in Sydney.

Great article about brave men. Knew nothing before of these operations.

What a tremendous story of courage and tenacity. Too bad their second raid failed and they were captured. So many that did so much with so little, what gallantry!