By Victor J. Kamenir

Early in World War II, a bitter joke circulated within the Soviet military. It ran, “What is the first thing Russia does when war is declared? It scuttles the fleet!” The joke referred to sad events in Russian naval history. In 1855, after the Crimean War, Russia lost the right to maintain a fleet in the Black Sea, and in 1904-1905 during the disastrous Russo-Japanese War, Russia lost two out of its three fleets. In 1941, the Soviet Union, born out of old Imperial Russia’s ashes, almost lost its Baltic Fleet.

Containing the Soviet Fleet

In 1940, without firing a shot, the Soviet Union absorbed the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, situated on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland. Along with territorial acquisition, this move was a major coup in projecting Soviet naval presence westward. Besides taking in the tiny navies and merchant marine fleets of the three states, the Soviet Red Banner Baltic Fleet acquired a number of important naval bases on the Baltic Sea. Chief among them was Tallinn, capital of Estonia and a major port city. A chain of several other bases, including a large one at Riga, the Latvian capital, extended farther west along the coast.

On June 22, 1941, mutual expansionist policies inevitably brought Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union into armed conflict. Lacking capital ships in the Gulf of Finland, which rated a low priority, the German Marinekommando Nord fleet consisted mainly of torpedo boats, minesweepers, and submarine flotillas, augmented by the small but skilled Finnish Navy. In contrast, its opponent, the vastly superior Soviet Baltic Fleet, was composed of two battleships, four cruisers, and 15 destroyers plus numerous smaller craft and submarines.

The rapid pace of the German invasion of the Soviet Union took the Soviet High Command by surprise. As German troops briskly pressed eastward through the Baltic States, the Soviet naval bases began falling like dominoes. The escaping Soviet naval vessels were being pushed farther east into the Gulf of Finland. By mid-August 1941, Tallinn had become the westernmost Soviet naval base on the Baltic Sea.

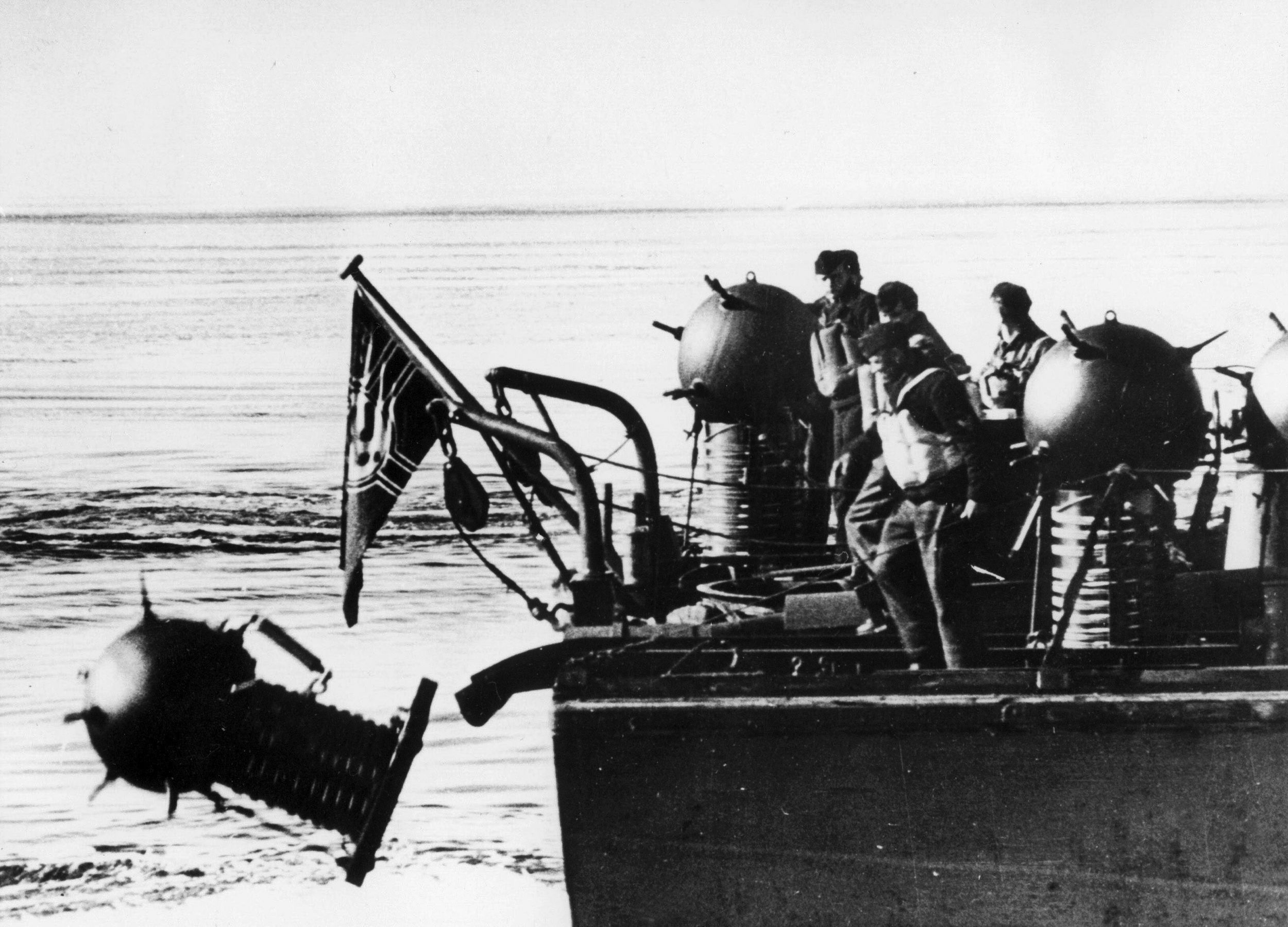

Just days before hostilities began, the German Kriegsmarine and its Finnish allies had begun laying extensive minefields in strategic locations in the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Finland. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Germans and Finns relied heavily on mines to negate the Soviet advantage and to protect their own shipping lanes. East of Tallinn, in the immediate vicinity of Cape Juminda, was a heavily mined area of the Gulf of Finland. This major minefield was designed to interdict Soviet operations between their Kronstadt base on Kotlin Island near Leningrad and the rest of the Baltic Sea. Overall, more than 2,000 mines were in place in Juminda waters.

From the opening of hostilities, the Soviet Navy lost the initiative despite its numerical and qualitative superiority. Its losses began to mount steadily, mainly falling prey to mines. Hardly a day went by without a ship sunk, often with all hands. Aggressively led German and Finnish light forces effectively cowed the Soviet naval presence in the Baltic.

On the landward side, Red Army forces were led by Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, who possessed the highest Soviet military rank but was not a capable military tactician. His paramount attribute was complete political reliability and unquestioning obedience to the instructions of Premier Josef Stalin. Despite his best efforts, Voroshilov was completely unable to shore up his crumbling front.

Driving toward Leningrad, German Army Group North brushed aside the Soviet Eighth Army, the closest Soviet formation to Tallinn. No plans to defend the city from a land-based attack were prepared before the war, and it was too late now. On July 22, the Germans struck at the juncture of the X and XI Rifle Corps of the Eighth Army. As a result of this action, the X Rifle Corps was cut off from the rest of the army and fell back to the vicinity of Tallinn. On August 5, the Germans cut the Tallinn-Leningrad railroad and reached the coast of the Gulf of Finland. Tallinn now lay 200 miles behind the German lines.

The Defense of Tallinn

Responsibility for defending the city and the naval base fell to the commander of the Baltic Sea Fleet, Admiral Vladimir F. Tributs. The Red Army forces available for defense were woefully insufficient, consisting mainly of the depleted X Rifle Corps and the 22nd NKVD (Secret Police) Division, which had performed guard and escort duties in the Baltic states before the war, shuttling prisoners to the horrific gulags.

To supplement the Army troops, any sailors who could be spared from the ships were formed into naval infantry detachments to fight on land. In addition, all naval shore facilities were swept of nonessential personnel, and they were placed in naval infantry detachments as well. These measures produced more than 10,000 sailors to bolster the city’s defenses. Additionally, several militia regiments totaling close to 4,000 Latvian and Estonian communists and volunteers joined the defenders. There was no time to train the sailors and militia units in infantry skills, and they suffered appalling casualties in the subsequent fighting. Initially, there were not enough rifles to arm them, and the weapons had to be flown in from Kronstadt.

Because of the weakness of the ground forces, artillery became the backbone of Tallinn’s defenses. Ships anchored in Tallinn’s harbor provided fire support for ground units. Numerous naval spotter teams were placed with the ground units to facilitate fire control, but frequent communication difficulties made the massive naval gunfire often ineffective. Still, on many occasions, all that prevented German breakthroughs was the tremendous volume of fire provided by the cruiser Kirov and her destroyer escorts. Additional fire support came from large-caliber shore batteries, some mounting 305mm guns.

As the Germans came closer and closer, the Red Air Force lost its airfields as well, with most of the surviving aircraft flying east where they joined in the defense of Leningrad. A small number of older Ilyushin I-16 fighters belonging to the Soviet Navy continued operating for a time from a tiny landing strip jammed between a fishing village and the water’s edge. Eventually, they followed their Air Force counterparts eastward, and Tallinn was left without air support.

On August 21, the Germans breached the defenses of the city itself. Despite valiant efforts, the dwindling Soviet forces could not hold them back. Tallinn’s harbor was now within range of German field artillery, and Soviet ships began taking hits. This caused the ships to frequently change positions, reducing the effectiveness of their fire and further weakening the land defenses.

The Red Army Evacuates

Despite the gravity of their situation, nobody at the headquarters of the Baltic Sea Fleet, including Admiral Tributs, dared to ask Voroshilov for permission to evacuate the city. Punishment for being labeled a “panic-monger” was very real, often carrying the death penalty. Finally, on August 25, Tributs went over Voroshilov’s head and submitted a carefully phrased request for instructions to Chief of the Navy Admiral Nikolai G. Kuznetsov. The last portion of the report stated, “The harbors and piers are under enemy fire. The Military Council … is requesting your instructions and decisions concerning the ships, units of the 10th Corps and fleet shore defenses in case of enemy breakthrough into town itself and the pullback of our forces to the sea. Embarkation on transports in this eventuality would be impossible.” Tributs’s concern mirrored Admiral Kuznetsov’s own misgivings, and he took this matter directly to the high command. After much deliberation, permission to evacuate Tallinn and break through to Kronstadt was finally granted late on the evening of August 26.

With permission granted, the Soviets began frantic planning for the evacuation of over 200 ships and close to 40,000 military personnel and civilians. The ships gathered in Tallinn’s harbor were a hodgepodge of both warships and support vessels ranging in size from massive civilian passenger liners converted into transports to the heavy cruiser Kirov, destroyers, submarines, and tugboats.

Fortunately, while waiting for final orders, senior Soviet commanders had already put together contingency plans for evacuation. Now these plans had to be finalized and last-minute corrections made. At the same time, special teams began destroying military equipment that could not be evacuated. The city’s utilities and other infrastructure were also rendered inoperable to deny their use to the enemy.

Three Routes of Retreat

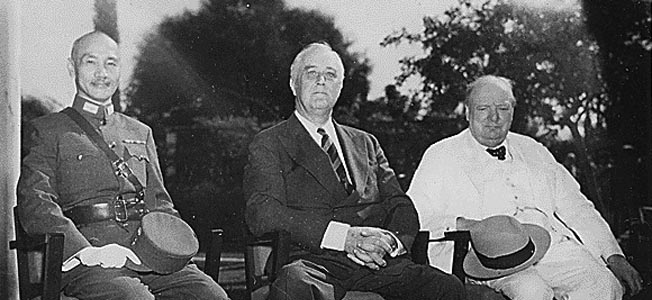

There were three routes of retreat to Kronstadt through the Gulf of Finland, which is only 20 nautical miles wide in some places. The northern route, close to the Finnish shore and under the enemy air support umbrella, was immediately ruled unacceptable even though it was almost completely free of mines. According to intelligence reports that the British government passed on to its Soviet allies, there were no German capital ships in the Baltic Sea or the Gulf of Finland. Lacking their own intelligence sources, the Soviet commanders still classified the British reports as unconfirmed and unreliable. Without any concrete data about the German surface fleet, Soviet admirals allowed for the possibility of German warships attempting to interfere with the run to Kronstadt.

The southern route would have taken the fleet along almost 200 miles of coastline occupied by German forces. Orders arrived from Voroshilov’s headquarters expressly forbidding Tributs to evacuate his fleet along this route. Ostensibly, these categorical instructions stemmed from the fact that this route would expose the fleet to treacherous and shallow waters and fire from German shore batteries. Several senior officers headed by Rear Admiral Yuriy F. Rall argued that this channel already had been successfully navigated by more than 200 ships. German artillery fire that could be brought to bear on the fleet would be conducted mainly by field artillery, easily countered by the heavier and more numerous guns of the Soviet naval vessels. Even a shore battery mounting 150mm guns captured by Germans at Cape Juminda was no threat to the Soviet ships.

The real reason for denying the southern route was Soviet mistrust of the Latvian and Estonian crews of numerous transports carrying evacuees and equipment. This paranoia was fed for two reasons. There was an incident in which a converted transport captained and crewed largely by Estonian civilian sailors had been intentionally run aground on the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland so that the crew could defect to the Germans. It was also feared that the crews of Soviet naval vessels, given an opportunity, might defect to the Germans.

Therefore, the Soviet high command ordered the evacuation from Tallinn to proceed along the middle route, even though it was thickly sown with German and Finnish mines. The Germans and Finns had been mining the waters of the middle route even before the German invasion of the Soviet Union, and the Axis sailors had been amazed at the apparent Soviet passivity.

Planning the Evacuation

The mission was made further hazardous by the dearth of minesweeping vessels. Obsessed with powerful warships, the Soviet shipbuilding industry had severely neglected the production of support vessels, and the Soviet Navy entered the war with a pronounced shortage of minesweeping capability. To further aggravate the problem, those minesweepers that were available were often used in capacities for which they were not designed, especially as transport ships. Admiral Rall and his staff estimated that almost 100 minesweepers would be necessary to adequately lead the Baltic Fleet during the breakout from Tallinn. Instead, only 10 modern minesweepers were available. They were supplemented by 17 older and slower converted trawlers and a dozen converted Navy cutters.

This small number of minesweepers was tasked with the gargantuan responsibility of shepherding more than 200 vessels to safety. The civilian transports, including 22 large ones, were divided into four convoys, each closely guarded by a few small naval vessels and led by older trawler minesweepers. The naval force was split into three elements: the main force, the covering force, and the rear guard. Ten modern minesweepers were allocated five each to lead the first two combat elements, particularly safeguarding the Kirov.

According to plan, the civilian and military convoys were to leave Tallinn on a staggered schedule. The Soviets were well aware of the danger posed to the convoys by mines off Cape Juminda, and they developed a schedule to allow the ships to traverse the minefields during daylight hours.

The evacuation route was divided into two portions, from Tallinn to Gogland Island, roughly in the middle of Gulf of Finland, and from Gogland to Kronstadt. The first section presented the most danger because of the minefields off Cape Juminda and the lack of air cover. Reaching Gogland Island by nightfall, the fleet would be within range of air cover based at Leningrad and Kronstadt. In addition, a task force of ships from Kronstadt was organized and stationed at Gogland to assist in any rescue and recovery efforts.

The whole operation would require very careful timing. Under relentless German pressure, Soviet ground units were barely holding the line on the outskirts of Tallinn. Admiral Tributs and his staff realized that some of these troops would have to be sacrificed and abandoned to fight hopeless rearguard actions, allowing the majority of forces to embark aboard ships. To avoid a panicked retreat to the harbor, the forward units were not informed about the pullback until the afternoon of August 27. Barricades were erected in the streets for the last-ditch defense. But as they observed NKVD troops manning barricades, many people came to realize that the barricades went up not to halt the Germans but to prevent a panicked rush to the harbor.

Chaos at the Pier

By 8 pm, the withdrawal began in earnest under a protective barrage of naval gunfire. Instead of an orderly retreat, the embarkation immediately deteriorated into complete chaos. The Soviet defenders could no longer hold back the Germans, who continually shelled the harbor. Several transport ships, with shells falling around them, were forced to leave their embarkation stations without picking up their designated units and evacuees.

Crowds of soldiers, sailors, and civilians were surging back and forth along the piers, storming the gangways of waiting transports. People were trampled underfoot in the maddened rush to the ships. The scene was punctuated by exploding German artillery shells and backlit by the burning city. “The whole town appeared to be engulfed in flames; burning and exploding,” recalled Admiral Tributs in his memoirs.

While several transports cast off largely empty, the majority of vessels were overcrowded. Writer Nikolai G. Mikhailovskiy, attached to the headquarters of the Baltic Fleet, recalled, “The staterooms are filled to overflowing. People are standing, sitting and lying down in the narrow corridors and on decks. Many, coming off line after sleepless nights, settled on deck. One had to step over them in order to get from one point to another … The whole shore is aflame. It is strange that during a bright sunny day the harbors are darkened by smoke. Signals relayed by flags are impossible to see. The searchlights shine brightly. Only they can penetrate this incredible darkness.”

As the transports filled up, they cast off and slowly moved to their staging areas off Naissar and Aegna Islands across the bay from Tallinn. In many cases, people desperate to get aboard continued clinging to the gangways, often forcing the crews to cut the gangways in order to get clear of the pier. Over 23,000 troops, including more than 4,000 wounded and several thousand civilian evacuees, were taken aboard. Despite Vice Admiral Yuriy A. Panteleyev’s claim in his memoirs that not a single platoon was abandoned to the enemy, almost 10,000 more men were left behind on Tallinn’s piers.

The wind continued picking up throughout August 27, creating choppy seas and further exacerbating the chaotic embarkation. Because of these delays, the first convoy did not sail until noon on August 28, a full 12 hours behind schedule. The naval and civilian convoys stretched in a line more than 15 miles long. Owing to deployed minesweeps, which required slow speeds to be effective, the convoys crept along at under 10 knots.

Bombs from the Air, Bombs in the Sea

Things quickly began to go wrong. Less than one hour into the voyage and several miles east of Aegna Island, one of the minesweeping trawlers leading the first convoy hit a mine and disappeared under the waves within seconds. The appearance of a mine in waters considered to be safe shocked everyone. The most likely explanation for this tragedy was that the heavy winds and waves generated by the previous night’s storm tore loose the moorings of a mine and the gulf’s current carried it into the midst of the Soviet ships. This loss was the forewarning of swarms of loose mines that were to plague the Soviet convoys for the next two days.

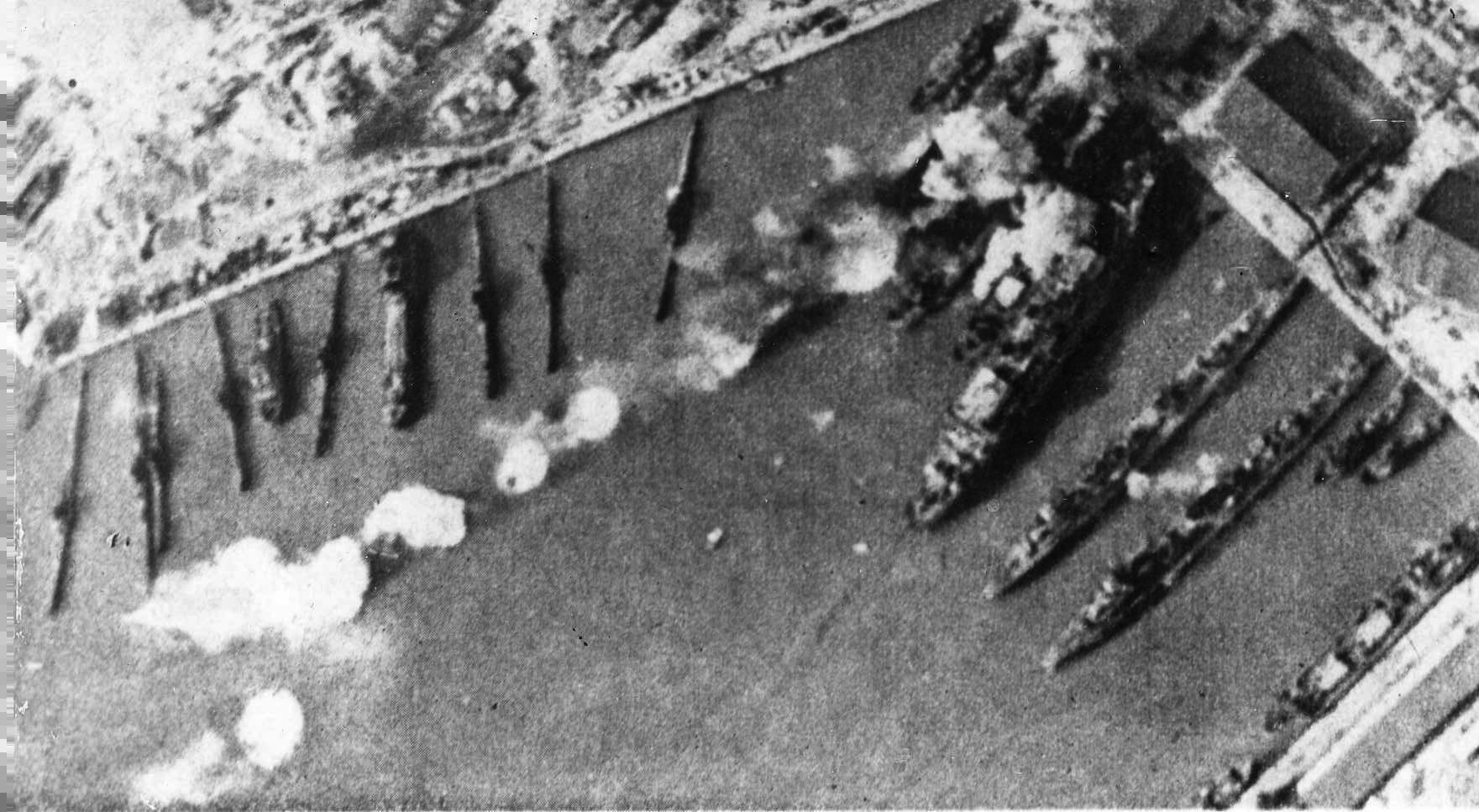

Undeterred, the convoy sailed on. German bombers appeared overhead and cautiously attacked the strung-out convoys. The Soviet Navy ships, spaced along the line of civilian transports, put up a spirited antiaircraft barrage and managed to keep the German planes at bay for a time.

Around 6 pm, the first civilian convoy arrived off Cape Juminda and its minefields. The nightmare began. At 6:05, a large explosion went up at the head of the convoy. The transport Ella, a passenger ship converted into a military transport, hit a mine and began to sink. The tugboat S-101, following in her wake and herself overloaded with evacuees, moved in to assist and hit a mine as well, virtually disintegrating. Of more than 1,000 passengers and crew aboard Ella, most of them wounded, fewer than 100 people were subsequently rescued. No one was saved from S-101.

(The Granger Collection, New York)

German aircraft now renewed their attacks. Shortly after Ella went down, the icebreaker Voldemars was hit by a bomb and sunk with significant loss of life. The large transport Vironia, a converted liner, was damaged by two near misses. Its upper decks, thickly packed with evacuees, were swept by steel fragments, tossing people aside in disfigured heaps and throwing overboard many passengers, both alive and dead. The rescue vessel Saturn moved in and took the damaged transport in tow. Several minesweepers, desperately attempting to keep the 200-meter channel clear, hit mines themselves and went down in quick succession.

Under relentless air attacks, Soviet ships were forced to maneuver to avoid the bombs. This compelled them to leave the narrow channel cleared by the minesweepers. Several naval vessels went down as if chasing each other to the bottom of the gulf. One of them was Saturn, leaving the practically immobile Vironia bobbing in the water.

Around 6:30, with the Soviet convoys floundering in the minefields in full view of Cape Juminda, a German battery, well-camouflaged in the wooded terrain, opened fire on the Soviet ships. However, its 150mm guns were no match for the ships’ heavier armament. One of the destroyers closed in and laid down a thick smoke screen, while Kirov replied with several volleys of its nine 180mm main guns. It was unknown whether the German battery was destroyed, but it fell silent.

More Casualties to Mines

There was no safety anywhere. Just before 10 pm, the submarine S-5, closely following Kirov on the surface, hit a mine and disappeared under the waves. Shortly thereafter, Kirov caught a mine in the right paravane, forcing the cruiser to stop. While a welder was lowered almost to the water’s surface to cut loose the metal pole with a torch, another mine became entangled in the left paravane. Valuable time was lost cutting loose and replacing both paravanes. While this was going on, the destroyer Gordiy, escorting the cruiser, hit a mine and lost mobility. It was eventually able to get moving again and limped to Kronstadt on its own.

Shortly after Gordiy was damaged, the venerable Yakov Sverdlov, originally commissioned in 1913 as Novik and lending its name to a class of destroyers, went down. Enjoying a distinguished combat record in World War I, this ship held a special place in Tributs’s heart as the only vessel the admiral had ever commanded. He witnessed the Sverdlov’s demise from Kirov’s bridge: “At 20:47 hours, suddenly a column of fire and smoke 200-250 meters high burst out from under Yakov Sverdlov’s body and settled down hissing, burying the surviving crew members … only several dozens of men were saved.”

As more and more ships sank or became disabled, the convoys lost cohesion and became intermingled. Naval detachments, moving on a nearly parallel course to the civilian convoys, often passed by the vulnerable and defenseless transports without providing fire support for them.

In the gathering darkness, lookouts were posted on the ships’ bows to spot mines. At about 10 pm, a mine exploded near the destroyer Minsk, the flagship of Rear Admiral Pantelyev. The explosion reverberated through the destroyer, bursting seams in multiple compartments and leaving the vessel inoperable. Pantelyev ordered another destroyer, the Skoriy, to render assistance. The majority of Pantelyev’s staff officers transferred to the other destroyer. Skoriy hardly had time to cast off and attempt to take Minsk in tow before also striking a mine, breaking in two, and sinking in front of stunned onlookers.

The slaughter continued. The frigate Tsiklon went down, falling prey to a mine. Only 15 minutes after Skoriy was lost, another destroyer, Slavniy, was soon damaged but remained afloat and continued moving under its own power. Shortly thereafter, the destroyer Kalinin, with Rear Admiral Rall aboard, hit a mine and began slowly sinking. As the destroyer Volodarskiy was transferring wounded crewmen from the Kalinin, it hit a mine as well and went under. Admiral Rall, suffering from a concussion, was taken aboard a cutter. The destroyer Artyom also went down.

(Map © 2008 Philip Schwartzberg, Meridian Mapping, Minneapolis, MN)

The toll of noncombatant vessels was also high. The damaged transport Vironia hit a mine and sank. Even a near miss from an exploding bomb would create havoc on ships overflowing with evacuees. The fate of immobilized wounded men, swathed in bandages and plaster and often trapped below decks in compartments blazing with fire or filling with icy water, was particularly terrifying. The ships of the first civilian convoy experienced particularly heavy casualties.

The Convoy Recuperates

As the convoys doggedly continued eastward, many of them had to navigate through floating debris fields and spreading oil slicks of destroyed and damaged vessels. In many instances, unable to stop, they mowed under the survivors bobbing in the water among dead bodies. Whenever possible, though, every effort was extended to rescue the survivors. Still, hundreds perished, succumbing to wounds and exposure. Hundreds more were plucked from sure death in cold water, desperately clinging to whatever pieces of debris that would float. In one truly miraculous instance, a sailor was rescued after clinging to a floating mine for hours.

Throughout the day there were multiple false sightings of German submarines. Every time a phantom periscope was spotted on the surface, one or two destroyers or sub chasers would dart out and drop depth charges. Despite multiple claims by Soviet eyewitnesses, no German submarine operated in the area at the time.

Worried about attacks by German and Finnish torpedo boats as well, the Soviet ships twice opened fire on a group of unidentified small vessels racing toward the fleet. Because of the lack of coordination and communication, the torpedo boats thought to be enemy vessels turned out to be a Soviet detachment returning from screening and scouting north of the main channel. The friendly fire incident resulted in one Soviet torpedo boat taking a direct hit and disintegrating.

With darkness falling, it became impossible to navigate the mine-studded waters, and Admiral Tributs ordered all ships to halt where they were. Even though this went against accepted naval doctrine, the halt at least eliminated the possibility of ships running into stationary mines. German aircraft disappeared with nightfall as well, and now the only danger lay with floating mines cast adrift in the waves. On most ships men lined up along the sides, armed with poles for pushing away the mines. In many cases volunteers took turns jumping into the water to guide the mines away from the ships with their bare hands.

During the halt, almost no crewmen were able to rest. Those not directly standing watch or dealing with floating mines were frantically conducting whatever repairs they could. Small cutters darted from ship to ship assessing damage. The scope of the disaster began to take shape. The destroyer force, representing the bulk of Tributs’s naval contingent, was cut in half. Admiral Rall’s rearguard force ceased to exist, and he was injured. Of the main force, only one destroyer and one frigate still accompanied the Kirov. Even worse, a significant number of the priceless minesweepers had been lost.

Abandoning the Transports

At dawn on August 29, good weather meant the return of marauding German bombers. Having moved clear of the minefields, the naval vessels, now unencumbered by mine sweeps and paravanes, raced ahead at more than 20 knots. Around 5 pm, Kirov’s group arrived at Kronstadt. Its hasty departure left the virtually defenseless transports at the mercy of German aircraft, which appeared around 7 am.

While significant numbers of German planes pursued the departing warships, especially concentrating on Kirov’s group, the majority of Luftwaffe aircraft fell upon the defenseless civilian transports. Beset by German dive-bombers, most transport captains gave up any hope of reaching Kronstadt. At most, they hoped to reach Gogland Island and disgorge their human cargo before German bombs could send them to the bottom of the gulf.

Shortly before 8 am, the large transport Kazakhstan, loaded with almost 5,000 soldiers and civilian evacuees, was damaged by bombs. Its captain, N. Kalitaev, was tossed overboard by the shockwave. Severe panic ensued aboard, with people jumping into the water. After heroic efforts, however, the crew of the transport managed to make minimal repairs and keep the ship afloat. After being thrown overboard and suffering a concussion, Kalitaev was rescued by a submarine and delivered to Kronstadt on the evening of August 29, a full day before Kazakhstan limped in. Arrested by the NKVD and accused of cowardice and abandoning his post, Kalitaev was promptly shot despite multiple testimonies of his innocence.

Under a rain of German bombs, the transports continued their race to Gogland. On many ships the soldiers desperately attempted to keep German aircraft at bay with rifle and pistol fire. As the hours ticked by, transport losses mounted to include Naissaar, Ergonautis, Balkhash, Tobol, Ausma, Kalpaks, Evald, Atis Kronvaldis, Skrunda, and Alev.

Several damaged transports managed to limp to Gogland and run themselves aground, disembarking their passengers. German aircraft easily found the immobile transports and finished them off. By the end of the day the burned-out hulks of transports Vtoraya Pyatiletka, Ivan Papanin, Lake Lucerne, and floating workshop Serp-i-Molot smoked on Gogland’s beaches. Still, despite tragic losses, more than 12,000 people were offloaded on Gogland Island and eventually shuttled to Kronstadt and Leningrad. But before they were taken off the island, German aircraft made several low-level passes, strafing the survivors with machine guns and dropping bombs. Scores of people who thought themselves safe died on this tiny speck of land.

As the transports were being pounded into oblivion by German aircraft, scores of smaller vessels slipped by Gogland Island and headed to Kronstadt. They continued the struggle until the afternoon of August 30. The Tallinn breakout was over.

A Success or a Disaster?

Events at Tallinn were comparable to the Allied evacuation of Dunkirk over a year earlier. At Dunkirk, 338,000 Allied soldiers escaped the Germans. This was accomplished under British air cover and over a much shorter distance, 20 miles compared with 200 at Tallinn.

The results of the Tallinn breakout are disputed as simultaneously a success and a disaster. Despite the loss of more than 11,000 evacuees, including roughly 3,000 civilians, almost 17,000 people, mostly evacuated ground troops, reached Leningrad and joined in the defense of the city. The Kirov was saved, along with the destroyers Minsk and Leningrad. Of the original 10 destroyers, five were lost, mostly of the old Novik class. The guns mounted on Kirov and the destroyers assisted in the defense of Leningrad, and the majority of the smaller naval vessels made it back as well. The real losses were among the civilian vessels, with more than 40 of them, including 19 large transports, sunk.

The Soviet government offered little official comment about the events. To this day, virtually no declassified information exists on the evacuation of Tallinn.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments