By Gene Eric Salecker

After the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many Americans in authority began to fear the large number of people of Japanese ancestry living along the West Coast of the United States, thinking that some of them might have sympathies for Japan and might assist in a possible invasion or sabotage American efforts to resist such an invasion.

Although it took a few months, President Franklin D. Roosevelt eventually issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, granting military commanders the ability to designate certain areas of California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska as off-limits to any people of Japanese ancestry. While about 200 people of Japanese lineage were removed from Alaska, another 112,000 were removed from the western states. Approximately 80,000 were Nisei—American-born Japanese with United States citizenship—while the remainder were Issei, Japanese-born immigrants who were eligible for U.S. citizenship under U.S. law.

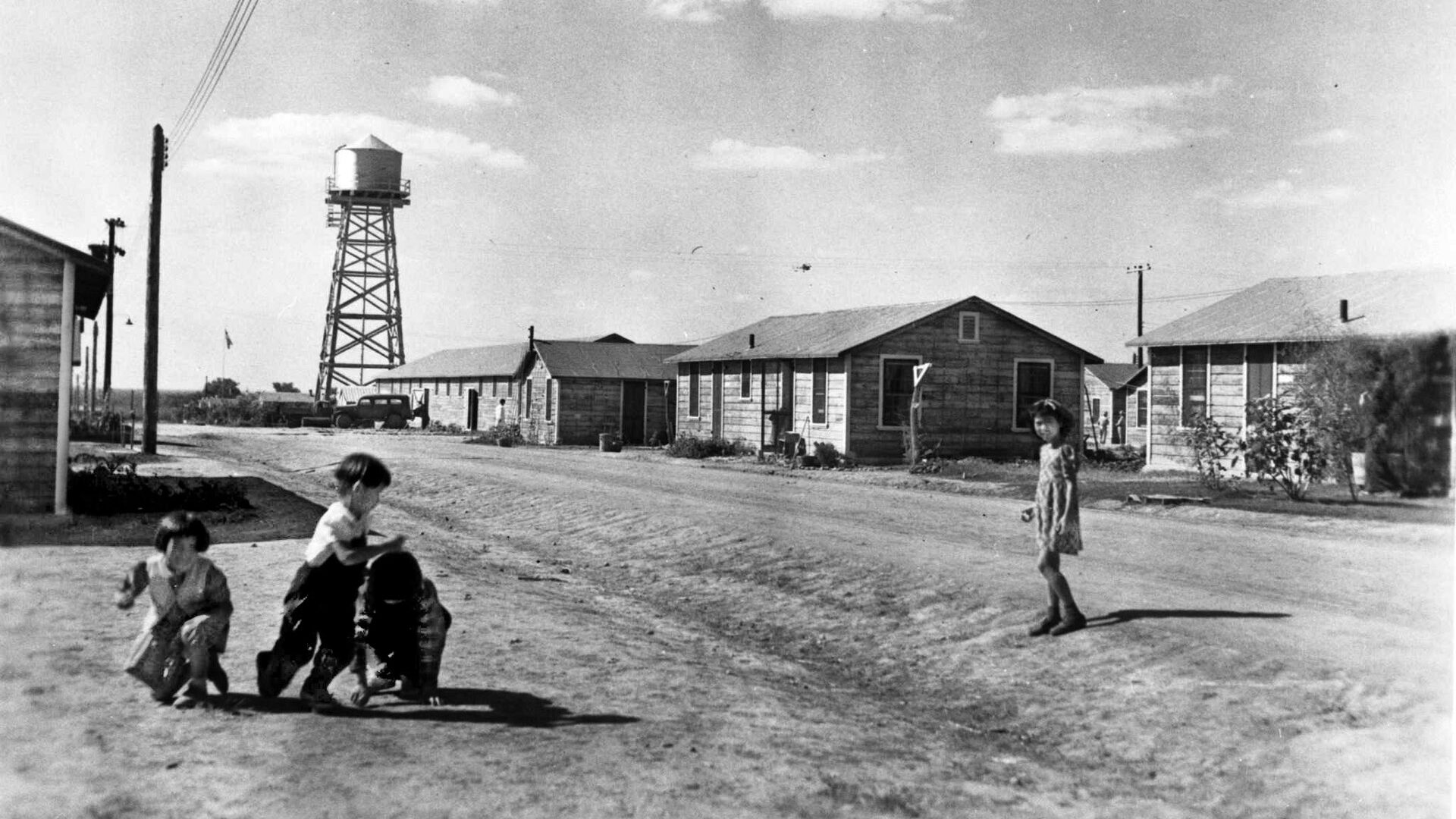

Removed from their homes and places of business, the Issei and Nisei were taken to relocation centers in several states, where they were forced to live in primitive housing units under harsh conditions. Surrounded by barbed wire, with guard towers pointing inward toward the compound, the new residents were forbidden to leave the premises under penalty of law. Told that they were being rounded up and removed from their homes for their own safety, the Issei and Nisei would not be allowed to go back to their homes until World War II was finally over.

Even before America began gathering up people of Japanese ancestry living along the West coast, authorities in Central and South America, and on the Caribbean island of Cuba, had been gathering up foreign nationals in their own countries. At the insistence of the United States government, 18 Latin American countries, including Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela not only swept up people of Japanese ancestry, but also those of German and Italian backgrounds. Taken from their homes, some of the detainees were sent to the United States and housed in detention camps in New Mexico and Texas operated by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), part of the Department of Justice, until they could be repatriated to Japan, Germany, or Italy.

In June 1940, President Roosevelt sent 700 FBI agents into several Central and South American countries to monitor the situation. Often, these agents overstated the threat of German influence in Latin America, exaggerating the threat of a fifth column. One agent mistakenly reported that the 12,000 ethnic Germans living in Bolivia were an “imminent threat,” ignoring the fact that 8,500 of them were Jews escaping persecution in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, in a move to secure the vital Panama Canal, the United States pressed the Panamanian government into making mass arrests of Japanese, German, and Italian nationals. On January 20, 1942, even before President Roosevelt had issued Executive Order 9066, the U.S. State Department had instructed its embassies in Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, and Nicaragua to contact the various governments and obtain agreements to lock up “all dangerous aliens” or send them to the United States for detention. At the Third Meeting of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the American Republics, held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in January 1942, the diplomats agreed to break off relations with the Axis powers and called for “the detention and expulsion of dangerous Axis aliens” from Latin America.

Large numbers of Japanese were living in Brazil (248,848), Peru (25,000), Mexico (5,100), and Argentina (5,398) in 1941, having emigrated in search of economic freedom and available land. After Pearl Harbor, Mexico, under pressure from the United States, relocated all of its Japanese citizens to Mexico City and Guadalajara. German and Italian residents deemed “dangerous” were interned at the city of Perote, about 150 miles east of Mexico City. Brazil and Venezuela, also under pressure from the United States, set up internment camps within their own countries, while Chile, in an attempt to stay neutral, used its own legal system to deal with foreigners considered a threat. In Paraguay, most of the Japanese nationals lived in one central area and were put under surveillance but generally left alone. Colombia rounded up about 100 German citizens and held them in the Hotel Sabeneta in the city of Fusagasuga. Only Argentina, which had pro-Fascist leanings, refused to go along with the United States and left its foreign nationals alone.

In Central America, Costa Rica arrested all the ethnic Japanese—mostly farmers—confiscated their property, and auctioned off their agricultural machinery. Originally held in the San Jose Penitentiary, they were later moved to an encampment that was quickly improved and cleaned up by the detainees themselves. In the Panama Canal Zone, German and Japanese detainees were housed at the U.S.-administered Camp Empire at Balboa City.

In Nicaragua, the 120 German and Japanese detainees, all males, were placed in a prison in Managua, where they suffered from a lack of washing facilities and inadequate food. In time, the older internees and those married to Nicaraguan women—about half the number interned—were moved to a confiscated German farm, where the living conditions and food resources were much better.

In the Caribbean, the entire Japanese population of Cuba, about 800, as well as several hundred German nationals, were rounded up and interned on the prison island of Isle de Pines (now Isla de la Juventud), under the southwest curve of the main island. Since Cuba was so close to the United States mainland, government officials in the Roosevelt administration took a special interest in the Cuban internment program, funding the entire operation.

Not surprisingly, at the other end of the North American continent, Canada—then a dominion of the British Empire—began rounding up German Canadians under the War Measures Act shortly after Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939. Interning both “enemy nationals and Canadian citizens,” the Canadian government eventually established 40 internment camps that held an estimated 24,000 Canadian German internees. In June 1940, after Italy entered the war, about 600 Italian Canadians were also rounded up and placed into three internment camps.

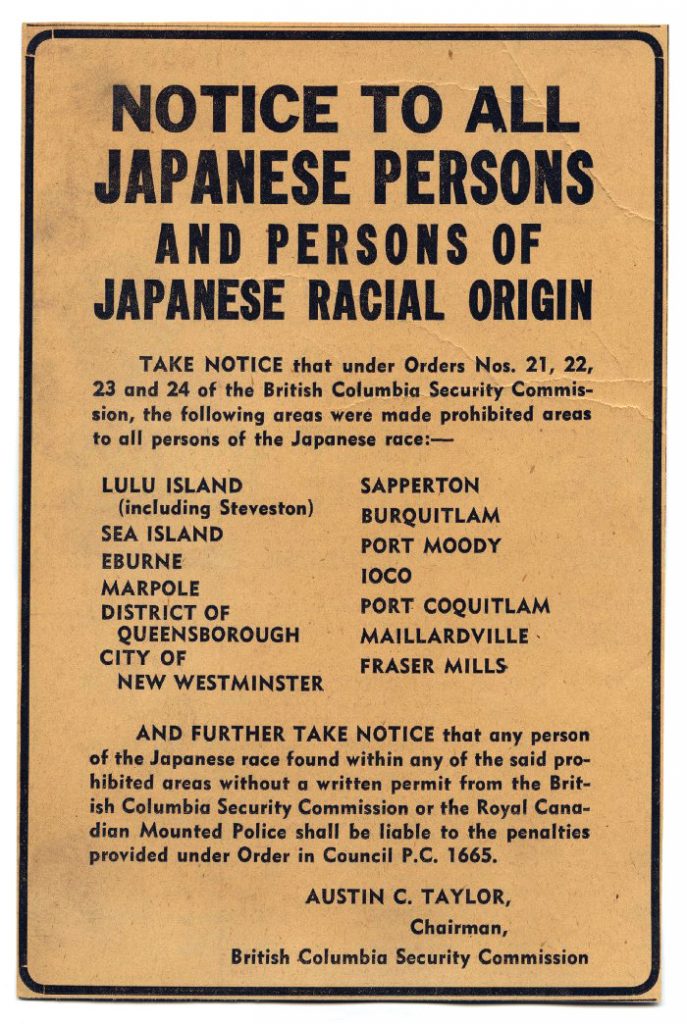

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police quickly interned 38 Japanese Canadians, and on February 24, 1942, only five days after President Roosevelt had issued Executive Order 9066, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King issued Order-in-Council P.C. 1486, ordering all Japanese Canadians to move 100 miles inland from the Pacific Coast to “remove the menace of Fifth Column activity from [the coast].” Some 22,000 Japanese, about 65 percent Canadian-born, were removed from their homes. Many of the Japanese Canadians moved into abandoned houses hastily refitted by the Canadian government at Slocan Valley, British Columbia. During the removal, an additional 720 Canadian Japanese who resisted the move were interned at a prisoner-of-war camp in Ontario. During the removal of the Japanese Canadians, the government confiscated and later sold their property to help pay for their relocation and detention.

Under United States Presidential Proclamation No. 2497, signed by President Roosevelt on July 14, 1941, Peru had placed hundreds of Japanese and Germans on a “blacklist.” On January 24, 1942, Peru officially broke off relations with Japan, and on February 12 declared war on both Japan and Germany. The Peruvian government then moved quickly against its foreign nationals, shutting down foreign schools, community organizations, and newspapers.

Although Peru toyed with the idea of placing its people of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry into internment camps within its own borders, they eventually decided to ship the detainees to the United States. On April 5, 1942, the first ship, Etolin, left Peru carrying 146 Japanese men, nearly all born in Japan and either all unmarried or with spouses already returned to Japan; 269 Germans; and 11 Italians. Steaming up the coast of South America, the ship stopped briefly at Ecuador to pick up 10 more Japanese and 38 more German deportees, and then at Colombia to pick up an additional 149 Germans and three Italians. On April 20, the ship sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge and docked at San Francisco. Once on U.S. soil, the men were denied visas and passports, classified as “enemy aliens,” and detained on the grounds that they had tried to enter the country illegally. Placed on a special 18-car train with blackened windows, the 626 South American detainees were sent on a three-day trip to a new detention camp at Kenedy, Texas.

Located 55 miles southeast of San Antonio, the facility at Kenedy was an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp that had been converted into the Kenedy Alien Detention Camp. Administered separately from the War Relocation Authority, which oversaw the running of the different internment camps holding American Issei and Nisei, the detention camps were run by the INS and the Justice Department.

In the wake of the first group, more Peruvian deportees were loaded onto the Swedish ship M.S. Gripsholm and the U.S. military transport ships Shawnee and Frederick C. Johnson. Many of these subsequent deportees were women and children, termed “voluntary internees;” they’d volunteered to leave Peru in search of their husbands and fathers, who had been taken to the United States aboard earlier transports. Once on U.S. soil, families were sent to a detention facility at Crystal City, Texas, while lone females and married couples without children were sent to Seagoville, Texas. As before, single males were sent to the Kenedy camp or a new facility at Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The 500-acre Crystal City Alien Enemy Detention Facility was located about 110 miles southwest of San Antonio, near the Mexican border, and was opened on November 2, 1942. Established on the site of an old Farm Security Administration migrant-labor camp from the 1930s, the Crystal City camp was segregated, having German detainees on one side and Japanese on the other. While the German side contained a

Hans Joachim Schaer was five years old when he was brought to Crystal City from Costa Rica. “The prison camp was beautiful, at least for us kids,” he wrote. “In the mornings we had a bottle of milk, we had a swimming pool, we had a dispensary, they treated us nice.” As Blanca Katsura recalled, “Being a child at the time, I had no worries and made lots of friends. We were able to go to school and learn Japanese.”

In February 1942, the INS acquired 80 acres of an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp from the New Mexico State Penitentiary near Santa Fe, New Mexico, and designated it Santa Fe Internment Camp. Opened in December 1943, the camp was originally intended to hold only Japanese families from Latin America but eventually held families of German detainees and “troublemakers” from the Japanese-American internment camps.

In all, 6,609 people of German, Italian, and Japanese ancestry were sent from Latin America to the detention camps in the United States, including 4,058 Germans from 18 countries, 287 Italians from 15 countries, and 2,264 Japanese from 13 countries. Of the 2,264 Japanese the Latin Americans sent to the States, 1,799—almost 80 percent—came from Peru.

In early 1942, through the assistance of Swedish, Swiss, and Spanish intermediaries, the United States and the Axis countries began talks to negotiate an exchange of both officials and private citizens. In May 1942, the Swedish ocean liner S.S. Drottningholm left for Lisbon, Portugal, carrying 652 German, Italian, Rumanian, and Bulgarian officials from the United States and 215 German and Italian officials from Latin America. Drottningholm returned to the U.S. with 908 American officials, newspaper correspondents, and civilians, including 241 from South America.

On June 3, Drottningholm set out on her second exchange trip, carrying 949 Germans and a handful of Italians, and returned with 949 North and South American passengers on June 30. On July 15, the Drottningholm returned to her home port in Gothenburg, Sweden, carrying 815 Germans and Italians from all over Central and South America, including 90 children and seven infants, who had been held at the Seagoville detention camp in Texas.

For the Japanese, exchanges began in mid-June 1942. It was estimated that as many as 3,300 U.S. citizens had been swept up by the Japanese in their attacks on China and through their early conquests in the Philippines and other Pacific islands. On June 18, 1942, the United States chartered the neutral Swedish motorship MS Gripsholm and put aboard 1,097 passengers. Many were Japanese-Americans from the United States, but over 200 were Latin American Japanese businessmen and officials and their families. Also aboard were Kichisaburo Nomura and Saburo Kurusu, the two Japanese emissaries that had been negotiating for peace with Secretary of State Cordell Hull when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Starting from New Jersey, the ship stopped at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to pick up another 409 Japanese internees, including diplomats and officials from the Japanese embassies in Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay, and then steamed to the neutral Portuguese port of Lourenco Marques, Portuguese East Africa (now Maputo, Mozambique). The ship returned to Jersey City with 1,451 Allied civilians, mostly American officials and their families captured in Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Indochina. Many of the repatriated Americans had been beaten and starved by the Japanese.

It took more than a year to work out another exchange with Japan. Because of security problems, legal issues, logistics, and the growing hatred between the two governments, the second exchange of nationals did not take place until the late summer of 1943. On September 2, the Gripsholm left Jersey City with more than 1,300 Japanese aboard, including 314 Japanese American detainees from the U.S. internment camps. The rest were Latin American Japanese from the detention camps. The ship picked up another 89 Japanese Latin Americans at Rio de Janeiro, and another 84 detainees at Montevideo, Uruguay.

The Gripsholm reached Mormugao, Portuguese West India and exchanged her passengers for 1,236 Americans, 221 Canadians, and about 40 Chileans from Japan. Included among the Americans were 461 missionaries.

The second exchange trip of the Gripsholm, like that of the Drottningholm, was her last. By late 1943, the deportations from Latin America to the United States had dropped off dramatically as the perceived threat from Central and South America diminished and the Allies began squeezing the Japanese defensive ring around their home islands.

At the all-male Kenedy detention camp, many of the detainees remembered the “tropical hurricane” that roared in from the Gulf of Mexico in late August 1942, tearing apart many of the hastily constructed “victory huts.” When the authorities ordered the Germans and Japanese to clean up the compound, many of them refused, arguing that such work did not constitute “regular camp maintenance” as stipulated in the Geneva Convention.

In September 1945, with the end of the war, President Harry Truman issued a proclamation authorizing the removal of all enemy aliens “who are within the territory of the United States without permission under the immigration laws.” The few remaining detainees at Kenedy were transferred to the facility at Crystal City, and the camp was officially closed down. At Crystal City, 2,371 Japanese, 997 Germans, and six Italians from Latin America awaited return to their countries in Central and South America. Unfortunately, Peru, which had sent almost 80 percent of the Latin American Japanese that had come to the U.S., refused to take back most of the detainees, accepting only those that could prove Peruvian citizenship. In the end, only 80 Japanese Peruvians were returned to Peru. The rest, almost 900, along with another 100 from other Latin American countries, were deported to Japan, where many of the Central and South American-born children had trouble adjusting to the language and customs.

Thanks to legal action pursued by civil-rights attorneys Wayne M. Collins and A.L Wirin, several hundred Japanese Latin Americans were allowed to stay in the United States as “undocumented immigrants” after the war.

In Canada, just before the end of the war, many Japanese Canadians were preparing to return to their homes along the west coast when Prime Minister King issued a new order-in-council giving the detainees only two options. With some help from the Canadian government, they could either resettle east of the Rocky Mountains, far from the Pacific Coast, or sign up for “voluntary repatriation” to Japan. The majority of Japanese Canadians agreed to move east of the Rockies, but almost 4,000 were shipped to Japan. Japanese Canadians were not permitted to return to the West Coast until April 1, 1949.

For those Japanese, German, and Italian Latin Americans who wanted to remain in the United States, Congress opened the door for them in June 1952, overriding a presidential veto and passing the Immigration Act of 1952.

On August 10, 1988, after years of lawsuits and negotiations, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, providing a formal apology on behalf of the United States government for the internment of the Japanese-Americans during World War II and granting each survivor $20,000. In September, Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney signed an agreement to compensate Japanese Canadians who had lost their property and been detained in Canada. Similar to the United States agreement, the settlement included an official apology by the Canadian government and a payment of $21,000 to each survivor.

Unfortunately, the Latin American Japanese did not qualify under the United States Civil Liberties Act of 1988, since they had not been United States citizens or permanent United States residents at the time of their detention. A class-action lawsuit was filed against the United States by the surviving Japanese Latinos, and in 1991, the United States government agreed to pay each person $5,000. Although many of the survivors were glad to finally receive some form of compensation from a government that had held them in confinement without due process of law, many of the survivors felt that the $5,000 payment was a mere pittance when compared to that given to the Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians.

To this date, there has been no formal apology or compensation from any of the Central American, South American, or Caribbean countries; nor has the United States offered any apology to the German or Italian Latinos deported from Latin America during World War II.

Author Gene Eric Salecker is a retired university police officer who teaches 8th grade social studies in Bensenville, Illinois. He is the author of four books, including Blossoming Silk Against the Rising Sun: US and Japanese Paratroopers in the Pacific in World War II. He resides in River Grove, Illinois.