By Richard Camp

Two days after receiving intelligence on the route of an important enemy convoy, the USS Sculpin (Sargo-class submarine SS-191) made radar contact with the Japanese ships near the Caroline Islands in the Western Pacific Ocean.

The sub’s captain, Commander Fred Connaway, ordered the boat to make a high speed run on the surface to gain a dawn attack position. After reaching a point ahead of the convoy, Sculpin submerged and began an attack on November 18, 1943. As Connaway took a quick periscope observation prior to launching torpedoes, sharp-eyed Japanese lookouts spotted the periscope, and the convoy’s escorts quickly forced the boat to “go deep.” The Sculpin rigged for silent running as Connaway skillfully maneuvered the boat to avoid the escorts’ futile attempts to locate her.

Connaway waited about an hour until the sound operator no longer heard the escorts’ propellers and ordered the Sculpin to come up to periscope depth. He scanned the horizon to see if there was another chance to attack the convoy. Finding nothing, he ordered the submarine to surface. Lt. George E. Brown, the submarine’s third officer related, “We surfaced in front of a Jap destroyer [Yamagumo (Mountain Cloud), DD 113) that had been left there as a ‘sleeper’ [to counter such a move].”

The Yamagumo spotted the submarine 600 yards off her port beam and launched a devastating attack. “Dive! Dive! Dive!” Connaway ordered. The diving officer took her down to 200 feet. Connaway gave the order to “rig for depth charge” and crewmen rushed to close the watertight hatches between compartments and secure everything that might come loose.

The destroyer raced overhead. Seaman 2nd Class Edwin K. F. Keller described how the destroyer’s “screws sounded like a freight train coming through a tunnel.”

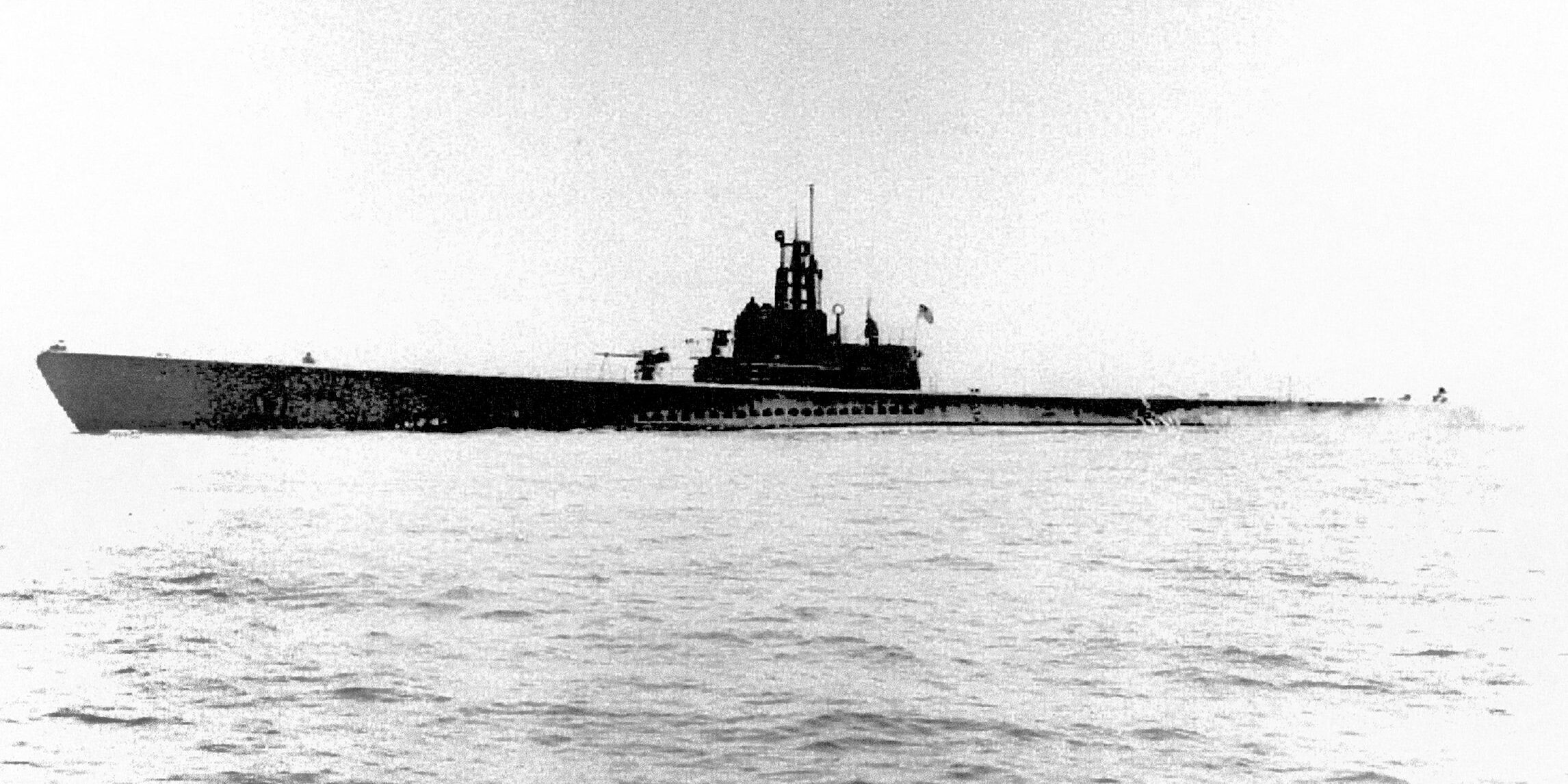

Commissioned on January 16, 1939, the diesel-powered Sculpin was named after a spiny broad-mouthed fish. She was a Sargo-class submarine, 310 feet long, with a 26-foot beam, and a 16-foot draft. With four General Motors V-16 diesel engines, she had a surface speed of 21 knots and 8.75 knots submerged. She had a range of 11,000 nautical miles at 10 knots. Sculpin’s batteries gave her an endurance of 48 hours submerged. Her test depth was 250 feet. She had eight torpedo tubes (four forward and four aft) and carried a total of two dozen 21-inch torpedoes. A three-inch gun was mounted on the deck forward of the bridge along with a 20mm cannon. Five officers and 54 enlisted men completed her crew.

Sculpin became famous when, on her shakedown cruise, she helped rescue the crew of the sunken USS Squalus (SS-192) in May 1939. Sculpin was the first to spot Squalus’ emergency red smoke bomb and rescue buoy. She established initial communications with the sunken boat and then directed the submarine rescue ship Falcon (ASR-2) to her location.

At 32, Connaway was a veteran submariner, having served three previous submarine tours (SS-123, SS-131 and SS-149), before taking command of the Sculpin for her ninth war patrol in November 1943. On her first eight patrols, Sculpin had been credited with sinking nine ships for a total of 42,200 tons and damaging 10 others, totaling 63,000 tons.

Also on board Sculpin this trip was Captain John P. Cromwell, Commander, Submarine Division 43, who was scheduled to form a mid-Pacific wolf pack including Sculpin, USS Searaven (SS-196), USS Spearfish (SS-190), and USS Apogon (SS-308)—in the event the Japanese fleet sortied from its base at Truk in the Carolines. Although Cromwell was senior in rank, Connaway was in command of the boat.

The sound operator heard the splashes of Yamagumo’s depth charges hitting the water. The 600-pound charges sank to their prescribed depth and exploded close aboard, causing the Sculpin to reel from the concussion. The sound reverberated inside the boat. The explosion of the second salvo damaged the boat’s depth gauge, unbeknownst to the diving officer—causing it to stick at 125 feet. An exhaust valve in the after engine room ruptured, and the compartment started taking on water. Several sea valves were jarred off their seats and could not be made watertight. “The damage received by the first depth charges was not unusual but disconcerting,” Brown said.

Connaway maneuvered the boat away from the searching destroyer until a timely rain squall enabled the submarine to evade its immediate attacks. However, when Connaway attempted to come up to periscope depth a second time, the Sculpin broached because the diving officer believed the boat was still 125 feet below the surface. A crewman in the forward torpedo room shouted over the battle phone, “The bow is out of the water!”

Yamagumo spotted the surfaced boat and immediately attacked. As the Sculpin tried to make a crash dive to safety, the crew heard the unmistakable sound of depth charges splashing into the water. At the first explosion, the boat shuddered violently and plunged further into the depths. A second and third explosion, each coming closer, brought paint chips and cork insulation fluttering down on the crew. Light bulbs shattered. The outboard vents in both torpedo rooms were severely damaged and leaking.

“The hands on the depth charge gauge fell off in front of my face. The pressure gauges near the diving station commenced flooding,” Brown described. The concussion “jarred holy hell out of us,” Baker said.

A fourth blast knocked out the boat’s sonar and damaged the steering and diving plane gear. It tore the radio transmitter from the bulkhead and smashed the receiver. Water sprayed into the compartments from numerous leaks, shorting out electrical equipment. The diving officer lost control, and the boat plunged well below its safe operating depth of 250 feet. The pressure gauges around his diving station were all flooded out. Tons of water in the forward torpedo room forced the bow down. The boat’s engines had to run at high speed to keep from sinking further. The engine noises made it easier for the Yamagumo’s sonar to track the Sculpin.

Brown surveyed the damage. “I found the after engine room had flooded to such an extent that I believed it unwise to attempt to place a bubble in No. 4 Main Ballast Tank, which would have aided the trim considerably. The flow of water forward might short the main motor leads. We decided to bail the water forward to another compartment until we could trim the ship without endangering the main motors.” Temperatures in the sub reached more than 100 degrees.

Fireman 1st Class Joseph E. Baker said, “The air was getting worse and the heat was horrific.” The bucket brigade was exhausted and making little headway with the rising water.

The Sculpin could no longer stay down. The battery power was almost exhausted, and it was still six hours until sundown and the possibility of evading the destroyer. In a last-ditch effort to save the boat and her crew, Connaway decided to fight it out on the surface.

“Commander Connaway had been so calm, resourceful, and persevering during the five hours of severe depth charging that it was hard for the crew to realize that the situation was as serious as it was,” Brown recalled.

A member of the crew witnessed a debate between the two senior officers.

“Captain Cromwell asked the skipper to keep the boat down,” he recalled. “No, we’re going to battle surface,” Connaway replied. “The skipper wanted as many men as possible to escape,” the crewman said.

Brown recalled, “As he [Connaway] started up to the conning tower, he ordered me to make sure the Sculpin was scuttled in case we lost the one-sided engagement with the destroyer. He still maintained his calm, collected, courageous manner.”

Connaway and the gunnery officer took position on the bridge, while the executive officer stayed in the conning tower. Connaway ordered, “Battle stations gun action. Deck gun only.”

Chief Signalman W. E. “Dinty” Moore asked Connaway, “Don’t you want to make ready the tubes?” “No, just battle surface.” Bill Cooper who heard the exchange stated, “If we’d have had those tubes ready for that Japanese ship, all we would have had to do was aim the boat at him and fire the torpedoes with a one-degree spread. We were just sitting there dead in the water.”

Moore recounted, “I think the skipper had just given up. He knew we didn’t have a chance.” With only one three-inch deck gun, the Sculpin was seriously outgunned. The Yamagumo had six five-inch dual-purpose guns, numerous antiaircraft guns, eight torpedo tubes, and racks holding three dozen depth charges.

Baker recalled, “They had dropped 52 600-pound charges, which is a lot of TNT. But the crew wasn’t about to give up without a hard fight first.”

The gun crews popped the hatches and swarmed up on deck. Crew members manned the 20mm cannon and 3-inch deck gun. Fireman 1st Class Joseph E. Baker was one of the eight-man crew manning the submarine’s gun. “We dashed out on deck quickly to have it out once and for all,” he remembered. “We were going to fight it out. The day was a pretty one, with white caps coming over the decks. At first when we went out on deck we couldn’t see the destroyer. Then one of the men spotted it on the starboard side…right against the sun. He was about 3,000 yards off. Immediately we went to our stations on the gun and began to fire at him. We got off the first shot, which went over him. The second round fell short. We had time to get eight rounds off, but all went over the destroyer.”

The Yamagumo maneuvered to get out of the line of fire from the submarine’s deck gun. Finally, she returned fire with her six-inch guns. The first salvo straddled the submarine, sending columns of seawater into the air. Then came the second salvo.

“One of the shots hit us in the main induction, another went directly through the coming tower and came out the portside, killing a number of men inside, and also some men who were out on deck, hiding from the gunfire,” Baker said. The enemy destroyer closed the range and opened up with machine guns.

“Men were being killed from the fire as they came out of the hatches,” Baker recounted.

The bridge watch team—Connaway, his executive officer, Lt. John N. Allen, and Lt. Joe Defrees, the gunnery officer—were all killed. Their deaths left Brown in command. The condition of the heavily damaged and sinking boat left him with no other choice. He ordered the crew to abandon ship and the boat to be scuttled.

“I informed Commodore Cromwell, who was in the control room, of my intentions,” Brown said later. “He told me to go ahead but he said he could not go with us because he was afraid that the information he possessed might be injurious to his shipmates at sea if the Japanese made him reveal it by torture.”

“I know too much,” Cromwell said. He had knowledge of the intimate connection between submarine operations and the U.S. Navy’s intercepts of Japanese communication.

Brown wasted no time in scuttling the boat. “I considered it unwise to wait longer because the next shell might damage the hydraulic system, making it impossible to operate the vents,” he recalled. “I then rang up, ‘Emergency speed’ and sent two chief petty officers to pass the word to abandon ship.”

When the petty officers returned to the control room, they waited “a minute by the clock,” then Brown ordered the vents opened. He knew it would only take minutes for the Sculpin to sink…not enough time for the Japanese to put a salvage team aboard.

“We heard the vents being pulled, so we dove into the ocean,” Dinty Moore said. Other men scrambled out of the hatches.

Torpedoman’s Mate 3rd Class Harry Toney explained, “We started out through the conning tower when we got word to go through the forward engine room hatch. I ran forward to the conning tower and remember seeing the destroyer standing by, firing dead away. Everyone was diving overboard, so I dove, too.”

Machinist’s Mate George Rocek was on deck when a shell hit the submarine. “I was momentarily stunned and numb all over,” he remembered. “After seeing that I was intact, I jumped over the side.” Rocek had been peppered with shrapnel but not seriously wounded. Electrician’s Mate 3rd Class Eldon Wright headed topside. “I started to go to the conning tower but just before I reached it, a shell hit it and I jumped over the side,” he said.

Several men rode the ship down. Ensign W.M. Fiedler elected to stay with the sinking boat. A crewman saw him in the wardroom with one of the Filipino stewards urging him to abandon ship. “We do not choose to go with you,” Fiedler said. “We prefer death to capture by the Japanese.”

Brown recalled, “As I left the conning tower hatch, water was coming waist deep over the sill, and I am certain no one left the ship after me.”

The Japanese destroyer continued to fire on the Sculpin and her crewmen in the water before dispatching ship’s boats to rescue the 42 survivors. Moore said, “Every one of them were leering at us. They all had guns.”

One badly wounded sailor was thrown back in the sea because of his condition. Many of the survivors on board the Yamagumo were wounded. “There was blood all over the place,” Keller recalled. He didn’t realize he had been wounded. “I looked down at my chest and saw blood everywhere. It was dry, but right then I thought I was going to die.”

Yamagumo sent a message announcing the Sculpin’s destruction, which was immediately picked up and decoded by Station HYPO, the U.S. Navy’s intercept station in Hawaii. Capt. W. J. Holmes in Double Edged Secrets: U.S. Naval Intelligence Operations in the Pacific during World War II wrote, “Some eight hours later, the Japanese destroyer Yamagumo reported sinking a submarine…when the Sculpin remained silent we knew that she had gone.”

The survivors were taken to the Japanese naval base at Truk and brutally tortured for 10 days before being loaded on two aircraft carriers—Chuyo and Unyo—that were returning to Japan. Chuyo carried 21 of the survivors in her hold. On December 2, the carrier was torpedoed and sunk by the USS Sailfish (SS-192), and 20 of the American prisoners perished. One man was saved when he was able to grab hold of a ladder on the side of a passing Japanese destroyer and hauled himself on board. The 21 survivors on Unyo arrived at Ofuna, Japan, on December 6, and were sent to labor in the Ashio copper mines for the duration of the war.

Ironically, the Chuyo was sunk by Sailfish, which Sculpin had helped to locate and raise after that submarine, then named Squalus, had been sunk some four and one-half years before.

Author Richard Camp is a retired U.S. Marine colonel and Vietnam veteran. He has written 13 fiction and nonfiction books and more than 100 articles.

It’s so sad to hear these stories. But, they’re often fascinating too