The history of our civilization is largely the history of military campaigns. As I have said here before, we are who we are and think what we think owing to the outcome of battles long ago—and not so long ago. It is odd, then, that military history has left us so little, physically, to see, to touch, to walk around in. If we travel

to a battlefield, even recent ones but certainly these centuries and millennia past, there is not much to see. Nature has taken back the hills and gullies, the fields and roadways where armies clashed and agonies raged. There is not much of a military presence in the green fields that were once the holocaust of World War I in France or among the trees and glades of Chancellorsville in Virginia.

Wars don’t build up; they destroy. Where there are ruins after a battle, the survivors tend to want to clear them away, so as not to be reminded of the devastation, or rebuild them anew as if they never were harmed. At any particular place, military presence arrives with thunder, but then rolls on, leaving little.

The striking exception is castles. These are very much the product of military activity and are tangible indeed. They are huge—they are often visible for miles—and you can certainly walk around in and touch them.

In a way, castles are the military mind frozen in stone. Their military architects built them as if they had campaigns in mind, anticipating equipment and tactics of attackers then building to thwart not only the attackers’ weapons, but also their movements by making them turn in directions to the liking of the defenders.

Even the fortresses of the Mycenean Greeks, notably at Mycenea and Tiryns, contained constructions that turned would-be conquerors between two walls, the better for defenders to fire at them from both sides.

During what might be called the Golden Age of castles in Europe—the 13th century—military architects fashioned twisting corridors that would slow and disorient attackers who might have pierced a gate as well as subject them to surrounding fire, even overhead fusillades.

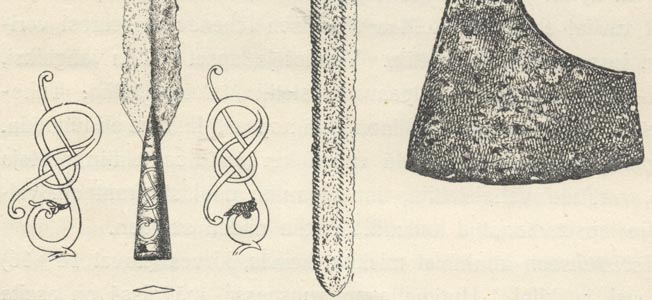

Fortunately those days are gone and castles are delightful to walk around in. The military ones—not the later ones built for comfort and prestige—are fascinating visions into the military minds of the day: Moats to keep attackers from the walls; drawbridges over moats that can be raised and shut; towers beside them to thwart attackers should they reach the door; walls of immense width and height; spiked portcullises just inside the drawbridge; and tortuous corridors lined with archers’ slits. Should attackers penetrate all this, they often had another, or three, concentric rings of defenses yet to overcome before reaching a castle’s heart and headquarters. Then there were the circular stairs rising clockwise to put a right-handed attacker attempting to rise at a disadvantage to a right-handed defender above him.

Attackers had their own bag of tricks: Filling a moat or ditch with rubble until they could cross; siege towers higher than the castle walls; battering rams or catapults hurling boulders to demolish the walls; and mining under the walls to bring them crashing down. To these the defenders parried with fire arrows against towers and rams and countermining against mining.

Castles are wonderful places to visit, and they set the imagination awhirl. It is difficult to walk through one without wondering at the enormous amounts of energy and wealth consumed in their creation. Years, even decades, of toil, that absorbed the energies of carpenters, masons, laborers, quarryworkers, stone transporters, all of which must have been a tremendous drain on the local economy. And yet they were built, and many still stand in fairly good condition after eight hundred years.

Unhappily my local libraries are scarce on good books about military castles, preferring the later ones. Web sites don’t offer up lots of intriguing information either, but the Europeans know moneymakers when they see them: The sites castlesontheweb.com, castles.org, and castlestour.com discuss castle tours.

Nowadays it is not the soldiers on the walls but the tourists paying the admissions that are preserving castles. And well they should be preserved. They can say more about a time and people than scores of books and prints.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments