By Major General Michael Reynolds

By the end of 1944, the Soviet Red Army had surrounded the Hungarian capital of Budapest and established strong defensive positions running from Esztergom on the Danube to Lake Balaton. On the last day of the year, the provisional government set up by the Soviets in those parts of Hungary occupied by the Red Army threw in its lot with the Allies and declared war on Germany.

Hungary, the last of Hitler’s partners in his European Axis, had deserted him—but not the Hungarian Army. In order to protect the country from the Bolsheviks, whom they feared and hated, what was left of the Hungarian Army continued to fight alongside the Germans.

On New Year’s Day 1945, the only sizable German reserves on the Eastern Front launched an offensive, code-named Konrad, to relieve Budapest and secure the southern Hungarian oil reserves. By January 6, General Herbert Otto Gille’s IV SS Panzer Corps had come within 25 kilometers of the Hungarian capital, but then, in the face of rapidly redeployed Soviet units, the attack stalled. On the same day, the Russians launched an attack across the Gran River, north of the Danube, with the equivalent of two tank divisions and four infantry divisions. Designed to disrupt the German offensive, the attack was successful and had advanced some 50 kilometers by the 8th.

German countermeasures succeeded in halting the attack, and by the 14th the Russians had lost half their gains and some 200 tanks; nevertheless, they still held a sizable bridgehead west of the Gran River.

In the meantime, Gille’s IV SS Panzer Corps had renewed its attack on January 10, and, after taking the Soviets completely by surprise, had advanced to within 21 kilometers of Budapest by the 13th. Then, despite Gille’s assurance that he was on the verge of a breakthrough, Headquarters Army Group South inexplicably called a halt.

SS Lieutenant Colonel Fritz Darges, commanding the 5th SS Panzer Division’s Panzer Regiment said later, “The head of our assault unit could see the panorama of the city in their binoculars. We were disappointed and we could not believe the attack was stopped. Our morale was excellent and we knew we could free our comrades the next day.”

Be that as it may, Hitler and the high command had other plans. On January 16, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of German forces more than 1,000 kilometers away on the Western Front, received the following order: “CinC West is to withdraw the following formations from operations immediately and refit them: I SS Panzer Corps with 1st SS Panzer Division LAH [Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler] and 12th SS Panzer Division HJ [Hitler Youth]; II SS Panzer Corps with 2nd SS Panzer Division DR [Das Reich] and 9th SS Panzer Division. Last day of refitting is 30th January.”

Also at this time Hitler sent his personal adjutant, SS Major Otto Günsche, to warn the Sixth Panzer Army Corps commander, SS General Sepp Dietrich, that within a month he would be required to move his army to the Eastern Front to launch a new offensive designed to secure the vital oil deposits in southern Hungary and perhaps even regain the oil of Rumania. Both Dietrich and General Heinz Guderian, the army group chief of staff, had wanted the Sixth Panzer Army deployed behind the Oder River to protect Berlin and northern Germany, but Hitler would have none of it. The only natural oil deposits in German-controlled territory were those around Nagykanizsa in southern Hungary, and, with Allied air attacks disrupting and often neutralizing the synthetic gasoline production sites for long periods, it was essential to protect them. Without this crude oil, the battle could not be continued. Dietrich and the trusted divisions of the Waffen SS were to be given responsibility for this new offensive, code-named Spring Awakening.

In view of the time needed to refit and move the Sixth Panzer Army to the Eastern Front and secure the ground west of the Danube for the new offensive, Hitler ordered a third attack in Hungary on January 18, using much- larger forces. This was designed primarily to cut off and destroy all Soviet troops north of a line drawn from Lake Balaton, through Székesfehérvar, to Budapest, and secondarily to liberate that city. The Pest garrison had in fact withdrawn across the Danube to the hills of Buda the night before.

Since the Russians had depleted their defenses in this area to meet the previous German attacks in the north, the new offensive was initially very successful. Within three days a large section of the west bank of the Danube had been secured 35 kilometers south of Budapest, and the Germans then turned north and northwest, threatening to link up with other forces attacking in the north and cut off an entire Soviet Front.

By the 26th, however, with their forces in the south only 20 kilometers from Buda and in the north half that distance, the Germans were exhausted, and this was the moment when Marshal Rodion Y. Malinovsky went over to the attack. Although the Germans continued to hold Székesfehérvar and the ground between it and Lake Balaton, by February 3 they were more or less back to their original positions. Buda fell finally on February 14. The siege had lasted 51 days and had cost the Axis over 70,000 men.

Meanwhile, Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s and Marshal Ivan Konev’s offensives in the north had advanced over 150 kilometers; Warsaw, Lodz, and Cracow had fallen, and a Soviet Army had entered East Prussia. The Red Army was now a mere 200 kilometers from Prague and, worst of all for the German people, it had crossed the Oder River and was only 70 kilometers from Berlin.

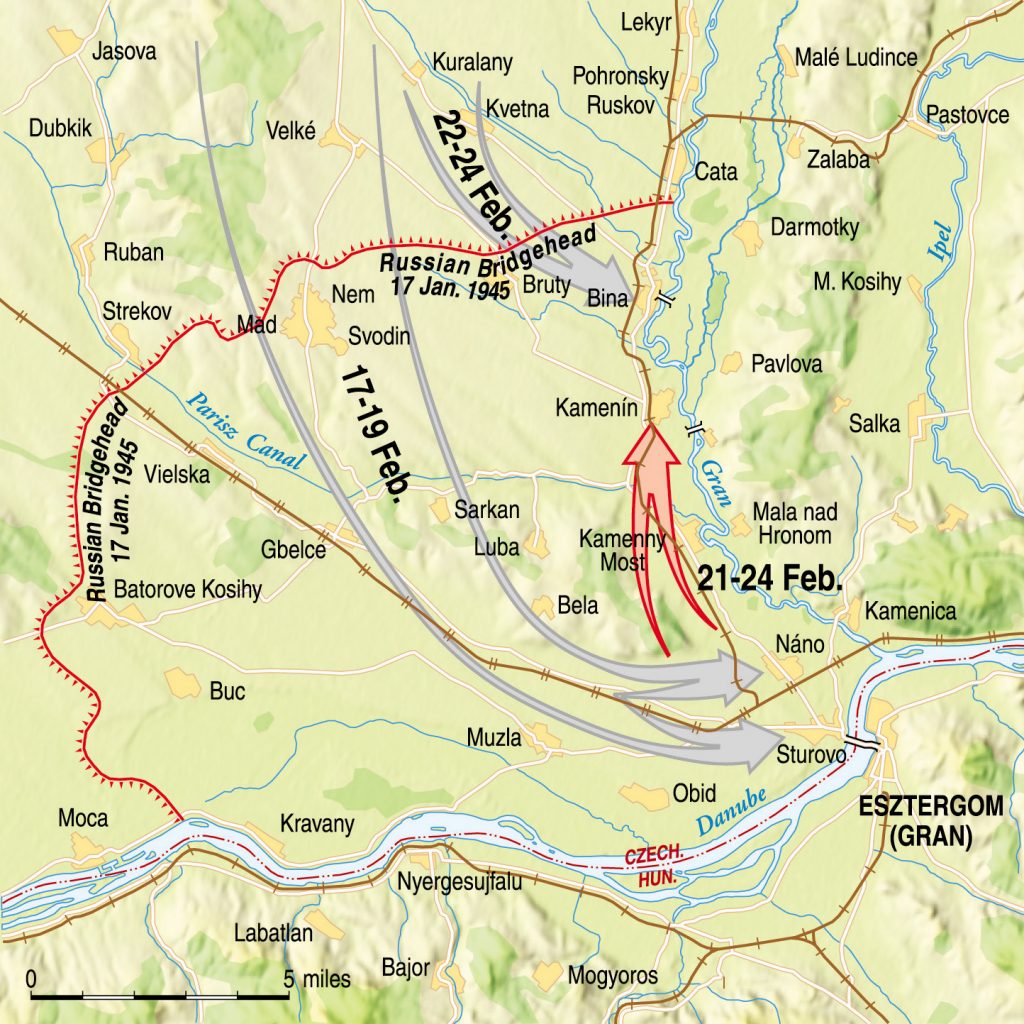

The Germans saw the Soviet bridgehead over the Gran River north of Esztergom as a potential assembly area for a major Red Army thrust toward Vienna, and as such it had to be eliminated before they could launch their own Operation Spring Awakening. Therefore, on February 13, Headquarters Army Group South ordered the commander of the German Eighth Army “to attack, concentrating all available infantry and armored forces, and accepting the consequent weakening of other front sectors, with the newly arrived I SS Panzer Corps…after a short artillery preparation, to thrust from the north, to destroy the enemy in the Gran bridgehead.”

The operation was given the code-name South Wind.

Although the bridgehead had existed for over a month, the Germans had no detailed intelligence of Soviet strength or dispositions within it. The operation order issued on February 13 merely stated that aerial photography and ground observation indicated that the Soviets were in a defensive posture. It also noted that a mechanized division was positioned in the center of the bridgehead, a guards mechanized corps and a guards tank corps “with the attached Sixth Guards Tank Army are probably located in the refitting area east of the Gran.” These units could be expected to reinforce the bridgehead if necessary.

The order added that there were known to be antitank blocking positions, supported by mortars to the west of Bruty, a continuous “fighting trench” running from Obid in the south through Muzla and Gbelce to just south of Bruty. The Parizs canal formed a considerable obstacle due to flooding, and although the roads and tracks were beginning to thaw out, they were not yet soft. Single bridges across the Gran existed at Bina and Kamenin, and there were two more near Nana.

In fact, the Soviets were much stronger than the Germans realized. In addition to the guards mechanized corps already mentioned, which provided a centrally located mobile reserve, there were two guards rifle corps in the bridgehead with a total of seven rifle divisions. Five of the rifle divisions were in perimeter defense, while the other two provided second echelon defense in depth. Even if these divisions were below strength, this would still mean that the Germans were up against well over 60,000 men with 100 to 230 tanks and self-propelled tank destroyers, over 100 antitank guns, some 200 heavy mortars, and over 200 guns and howitzers.

Containing the Soviet bridgehead before the opening of the German offensive were three German infantry divisions with one Hungarian infantry division and parts of another, supported by elements of a German panzer division.

The Germans were correct in their appreciation that the Soviet forces were in a defensive posture. Although a new offensive was being planned, this would not take place until mid-March, and in the meantime the troops west of the Gran were clearly vulnerable. The bridgehead was only 20 kilometers deep and 20 kilometers wide and, with a 30 to 40-meter-wide river behind them, it was clearly going to be difficult to reinforce the Soviet troops in the bridgehead or, in the worse case, withdraw them.

From the German point of view, the forthcoming battle was not without its problems. Mounting the main attack from the south across the Danube was obviously out of the question, and an attack from the west would run against the grain of the country. The Germans therefore chose to attack from the north. Even this had its difficulties. The Parizs Canal was a major obstacle due to the early thawing of the winter snows, and in the final stages of the advance the assault force would be compressed into a narrow corridor, less than 10 kilometers wide, by a ridge to the south of Luba and the Danube River.

Operation South Wind was to be led by Panzer Corps Feldherrnhalle. This corps consisted of three infantry divisions and an armored group of some 25 tanks. Its initial task was to seize the high ground, particularly Point 190, to the south of Svodin, but the villages of Svodin and Bruty were to be taken from the rear and any fighting there was not to be allowed to interfere with the general advance south. SS General Hermann Priess’s I SS Panzer Corps was to follow closely behind the Feldherrnhalle and, after crossing the Parizs Canal, was to capture the ridge running east from Gbelce before pushing on toward the Danube at Sturovo. A reinforced regimental group from the Sixth Army south of the Danube, known as the Hupe Regimental Group, was to establish a bridgehead across the river near Obid in the early phases of the offensive and cooperate with Priess’s men attacking from the north.

The Luftwaffe was tasked with supporting South Wind by attacking known antitank defenses south of Svodin and Bruty and in the Muzla-Luba sector, as well as delaying and destroying any Soviet reinforcements attempting to cross the Gran River.

From February 12-15, I SS Panzer Corps moved to a staging area around Nové-Zamky. Tracked vehicles moved by rail and those with wheels by road. A platoon commander in the 9th SS Panzer Pioneer Company recalled, “Rations were excellent. We learned from the civilian population the various uses of paprika. The people were very friendly. They recounted to us the good old days—Germany, Austria, Hungary. During the evenings we drove to see films in Nové-Zamky.”

Then, on the night of the 16th, the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH) and the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (HJ) moved again into a final assembly area behind the Feldherrnhalle. The latter’s infantry divisions were located in and around the villages of Ruban, Dubnik, Velk‚ and Kvetna, and the armored group near Farna. This was an ideal place to assemble with rolling hills and plenty of cover.

In readiness for the attack, SS Maj. Gen. Otto Kumm, who had only assumed command of the LAH on February 15, divided the available parts of his division into a Panzergrenadier Group under the command of SS Lt. Col. Max Hansen, Kampfgruppe (KG) Hansen, and a Panzer KG under SS Lt. Col. Jochen Peiper—soon to become infamous for his part in the “Malmedy Massacre.”

The former consisted of parts of the 1st and 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiments, a detachment from the 1st SS Reconnaissance Battalion, the 1st Company of the 1st SS Panzerjäger Battalion, and two 37mm flak batteries. Kampfgruppe Peiper was made up of 25 Panther and 21 Mk IV medium tanks in one panzer battalion under SS Major Werner Poetschke, 19 Tiger IIs of SS Lt. Col. Hein von Westernhagen’s 501st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion, the 3rd SS Mechanized Panzergrenadier Battalion, and part of the 1st SS Panzer Artillery Battalion. According to the divisional chief of staff, Ralf Tiemann, the rest of the division was still in transit to the new battle area when the offensive began.

Hubert Meyer, the chief of staff of the HJ, has stated that the 12th SS Panzer Division was more or less complete for South Wind and fought in its conventional groupings. He claims 38 Mk IVs, 44 Panthers, and 13 Jagdpanzer IVs were operational just before the attack. The only combat unit not mentioned in his account of the Gran bridgehead fighting is the 560th Heavy Panzerjäger Battalion. If, therefore, we exclude this latter unit, we have a figure of 160 operational tanks and Jagdpanzers in I SS Panzer Corps at the beginning of Operation South Wind, only 66 percent of its authorized holdings.

Despite the widespread flooding and poor road conditions caused by the early thaw, Operation South Wind began at 0500 hours on February 17. Leaving high ground on their right flank and with the Gran River on their left, the Germans attacked across open, rolling, agricultural land with few villages and no serious obstacles.

The artillery of I SS Panzer Corps joined in an opening barrage by the guns of Panzer Corps Feldherrnhalle, and in the most critical area of the attack, the center, the Russians were taken by surprise. By 0900 hours the leading elements of the 46th Infantry Division were near Point 190, having penetrated the Soviet defenses between Svodin and Bruty, but there they ran into an antitank screen and a few individual T-34 tanks. After calling for support from the LAH, a successful attack was launched at 1140 hours, and by 1700 hours elements of both the LAH and 46th Infantry Divisions had reached the Parizs Canal in the area of Sarkan only to find the bridges there destroyed.

A loader in one of Peiper’s tanks later remembered, “Peiper ordered five King Tigers to drive over the hill. What a sight! As on a silver platter, they appeared on the hill and immediately began taking fire from the Russian antitank guns. We saw the shells bounce off the front of the Tigers. That must have been a shock for the Russians, especially since the Tigers destroyed one antitank gun after another.… Peiper immediately gave the order: ‘Panzers—march!’ A hurricane of fire was released as the KG drove over the hill in formation.… The tanks and APCs drove at full speed, firing all barrels.… There was only one thing for the Russians to do—clear out.… KG Peiper suffered no losses.”

During the early part of the night, a small infantry bridgehead was established by KG Hansen, but no vehicles could cross. Nevertheless, it had been a good day for the LAH and its associated 46th Infantry Division. They had broken through the Soviet defenses and advanced nearly 10 kilometers.

On the left flank things did not go nearly so well, and the 211th Infantry Division of the Feldherrnhalle was stopped in front of Bruty by a guards rifle division in fortified positions supported by antitank guns, mortars and artillery.

Similarly on the right flank, the 44th Infantry Division of the Feldherrnhalle ran into strong opposition from the 6th Guards Airborne Division between Strekov and Svodin, and it was only after tanks joined in the attack that further progress could be made. By 1700 hours, Svodin had been captured and the advance continued toward the canal and Vieska.

What of the Hitlerjugend Division? It had followed behind the LAH, and during the afternoon the 26th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment was committed on the right flank of its sister division to secure a crossing of the Parizs Canal. The 1st Battalion of the 26th Regiment managed to make a crossing just to the north of the large village of Gbelce by about 2100 hours, and the 2nd Battalion followed into the shallow bridgehead. Soon after midnight, the 2nd Battalion had reached the road junction 1,500 meters northeast of Gbelce, and both battalions then went firm. A small canal crossing, capable of taking wheeled vehicles, was discovered in the same area. During the night the Russians counterattacked with a battalion of infantry and at least two T-34s, but were beaten off.

The commander of Army Group South, General Otto Wöhler, was anxious that the Soviets should not be allowed to recover their balance and build up a second defensive line to the south of the canal. To prevent this from happening, the Hupe Regimental Group from south of the Danube was ordered to cross the river that same night. This was achieved without opposition.

In the early hours of the 18th, KG Hansen expanded its small bridgehead, and Leibstandarte Pioneers (engineers) were able to bridge the Parizs Canal. Four T-34s were claimed by Hansen’s 6th SS Panzergrenadier Company during this fighting. Mines caused some further delay, but soon after midday the first of Poetschke’s Mk IVs and Panthers crossed the canal, and, despite an air attack by Soviet fighter bombers, by early evening KG Peiper had reached the Gbelce-Nana railway line, 3 kilometers north of Muzla.

Meanwhile, to the west of the LAH, the Feldherrnhalle’s 44th Infantry Division had forced a passage over the Parizs Canal near Vieska, and in the early afternoon its tanks were able cross. Then, in conjunction with the 26th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, a joint attack was launched on Gbelce. The Feldherrnhalle Group was joined by SS Major Hermann Brand’s 3rd SS Mechanized Panzergrenadier Battalion, and they took the western part of the town. The 1st Battalion captured the eastern sector, and the 2nd Battalion went on to secure the high ground 2 kilometers further east. By evening, infantry and armor of the Feldherrnhalle were in possession of Point 129, 3 kilometers south of Gbelce, and in contact with the Leibstandarte.

On the 19th, the weather improved, and at 0530 hours I SS Panzer Corps resumed its attack. KG Hansen of the Leibstandarte was given the task of clearing the enemy from the vine-covered ridge south of Point 250, while KG Peiper resumed its advance on the north side of the Gbelce-Nana railway. It was by no means an easy advance.

SS Lieutenant Rolf Reiser later described the action: “In the early morning our assembly was considerably delayed by

a Russian fighter bomber attack; we suffered the loss of several tanks and wounded.…We set out astride the road with seven tanks of the 1st Company. I advanced … between the road and railway line with the three Panthers of my Platoon.… Ivan attacked our open right flank at short range with tanks from behind the cover of the railway embankment. One of the Panthers … was hit and stalled.… SS Senior Sergeant Strelow, the 3rd Platoon leader, set up to the right of me. Then there was a detonation a short distance away and his tank was ablaze. I drove behind a shed and slowly probed the other side until I had the T-34 broad-side in front of me—no more than 50 meters away.…He burst into flames on the first shot, the turret flew off after the second! Then the Tigers and Panthers of the 2nd Company caught up and joined in the armored battle. Two more enemy tanks were destroyed.”

Farther to the west, SS Captain Hans Siegel’s 2nd SS Panzer Battalion of the Hitlerjugend, with Brand’s 3rd Mechanized SS Panzergrenadier Battalion attached, had formed up during the night to the south of Gbelce protected by the 25th and 26th SS Panzergrenadier Regiments. It too advanced at 0530 hours with grenadiers leading the way on both sides of the Sturovo road in case of mines and the tanks on the road itself. Shortly before daybreak, KG Siegel came under artillery and antitank gunfire from Muzla, but a quick attack, led by SS Lieutenant Helmut Gaede’s 1st SS Panzer Company, took the village, and the surrounding area was soon cleared by the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 26th Regiment.

While the HJ was preparing to resume its advance on Sturovo on the south side of the Muzla-Sturovo road by way of Obid, the division suffered a serious loss. SS Lt. Col. Bernhard “Papa” Krause was killed in a surprise rocket attack. He had been a stalwart of the HJ since its foundation and was revered by all its members.

The advance began again soon after midday, with the HJ moving on Sturovo from the southwest and KG Peiper of the Leibstandarte from the northwest. At about 1300 hours, when they were some 3 kilometers short of Sturovo, the infantry element of KG Peiper, the 3rd SS Mechanized Panzergrenadier Battalion, swung northeast to attack Nana. Poetschke’s Mk IVs and Panthers and von Westernhagen’s Tiger IIs were joined by 20 Sturmgeschutze armored vehicles and infantry of the Hupe Regimental Group from the Obid area for the assault on Sturovo.

In his citation for the oakleaves to Poetschke’s Knight’s Cross, Peiper wrote, “Rushing headlong and firing wildly, his tanks overran the antitank nets in front of Muzla and Sturovo, and after making contact with the Southern Group [Hupe], which had been ferried over the Danube in assault boats … pushed through to Esztergom.”

At the same time, an assault group from an infantry division holding Esztergom crossed the Danube and joined in the attack. The Russians had no chance in this vulnerable corner of their bridgehead, and before last light the men of I SS Panzer Corps were gazing at Esztergom cathedral, standing like a sentinel above the far bank of the mighty Danube. They knew they had completed the hardest part of their task. Nana and Sturovo were in the hands of the Leibstandarte and Hitlerjugend.

In other relevant actions on February 19, Batorove Kosihy and Buc were occupied by a KG of Army Group South following their evacuation by the Russians, and the 44th Infantry Division of the Feldherrnhalle captured Kravany on the Danube and the forest to its east. In the eastern part of the bridgehead, the 46th Infantry Division, with armored support, had cleared the wooded, hilly area just to the west of Kamenny Most, but, north of the Parizs Canal other elements of the division were repulsed by a Soviet counterattack 2 kilometers short of Kamenin. In the north, Bruty remained firmly in Russian hands.

From the outset of Operation South Wind, the Germans had been worried that the Soviets would attempt to reinforce their bridgehead. They had correctly identified parts of the IV Guards Mechanized Corp in the northern part of the bridgehead, but they were particularly worried about the whereabouts of the Sixth Guards Tank Army, and when aerial reconnaissance reported 3,000 vehicles moving north from the Budapest area, they became alarmed. Orders were issued for immediate night attacks on Kamenny Most and Kamenin. Leaving the bulk of the LAH armored group in Sturovo to replenish ammunition and supplies, the Mk IVs of KG Peiper, with part of the 46th Division, attacked from Nana along the Kamenny Most road. Another part of the 46th Division advanced north of the Parizs Canal on Kamenin. Both attacks failed, and Soviet air superiority and artillery fire from east of the Gran precluded any further attempts during daylight on the 20th.

A two-phase operation was then ordered. In the first phase, the LAH and 46th Infantry Division were to take Kamenny Most in the south of the remaining bridgehead, while the HJ, with support from the 211th Volksgrenadier Division (VGD), was to secure Bruty in the north. In a second and final phase, the twin divisions of I SS Panzer Corps would clear Kamenin and Bina, respectively.

Parts of KGs Peiper and Hansen, with support from the 46th Division, successfully entered Kamenny Most during the night of the 21st, but soon after dawn they were forced on to the defensive by Soviet artillery fire and continuous air attacks.

Rolf Reiser recalled, “Peiper had decided upon a night attack because we were covered by massive fire during the daytime from enemy artillery positions on the raised eastern bank of the Gran.…We rapidly crossed the softly rolling terrain directly under the chain of hills that ran west of the road and railway line.…We turned east … in order to penetrate frontally. Then massive Russian artillery fire was initiated. A curtain of iron and fire hung before us. Flares and tracers illuminated the night and showed us the way to the enemy positions…. We rattled across the railway—then there was a crack and flash of light. We were hit!… We caught fire immediately.… My gunner followed me as the last one out of the turret. We landed in a trench with Ivan, who was as surprised as we were. Armed only with pistols and bare fists, we defended ourselves…. We finished off the Soviets in the cover of the burning tank and the exploding ammunition.”

The assault was resumed with the coming of darkness, and by 2100 hours the last Russians had withdrawn from Kamenny Most.

Meanwhile, during the 20th and 21st, the Hitlerjugend was relieved by the 44th Infantry Division and moved to a new assembly area southeast of Farna in readiness for its assault on Bruty. The I SS Panzer Corps was thus poised for its final battles west of the Gran River. With aerial reconnaissance and other intelligence sources confirming that the IV Guards Mechanized Corps had withdrawn across the Gran and other troop movements toward the river had apparently halted, Hermann Priess and his men had every reason to be confident of success.

Headquarters Army Group South concluded that the Soviets must be expecting a German assault across the Gran. Therefore, defensive positions on the east bank were being prepared with all available reinforcements. In fact, Hitler had forbidden any such assault and demanded that his Leibstandarte Corps be freed as soon as possible for his new offensive, Spring Awakening, in the Lake Balaton area.

In preparation for its attack on Bruty, the HJ had to rely mainly on aerial reconnaissance and on information provided by the 211th VGD, which had already failed to take the village. This revealed that the area was heavily fortified, with minefields backed by large numbers of machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns in considerable depth. Since the ground was completely open, the decision was made to undertake a night operation.

The preliminary phases of the attack were marred by a number of unfortunate incidents. The 25th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, on the right flank, failed to reach its starting line in time for the assault, and, in the darkness, some of Siegel’s tanks failed to recognize the Panzergrenadiers who were leading the attack on the left and opened fire on them. Five men were killed, including a company commander, and another eight wounded. This second disaster alerted the Russians, who opened fire with machine guns and mortars.

Despite these problems, Siegel’s tanks began their attack at about 0445 hours in the wake of a bombardment by artillery, mortars, and rocket launchers. Within minutes, however, the leading tanks ran into a minefield, and several, including Siegel’s, were immobilized. These were repaired under fire, and the tanks then withdrew behind a reverse slope from where they supported the attack of the 9th Mechanized Panzergrenadier Company, led by SS Lieutenant Dieter Schmidt. This company was on the left flank of the attack and outside the minefield. Although some of its APCs floundered in the soft ground of a streambed, the rest managed to break through the defenders and reach the southern edge of the village.

In the meantime, the 25th Regiment had joined in the attack, and together with the other two battalions of Braun’s 26th Regiment took the western and lower sectors of the village.

An SS Sergeant Burdack of the mechanized battalion later described the scene: “The village was choked with enemy vehicles.…Several T-34s and T-43s [light tanks], still inside the village, forced the APCs to take cover.…The Russian tanks, without the protection of infantry, left…in the direction of Bina.”

An SS officer remembered: “Fire from our heavy weapons had badly damaged most of the buildings. Roofs had been stripped off; walls had crumbled. During the pitched battle, civilians came out of the ruins of their houses…unconcerned with what was going on around them…They were obviously happy beyond measure to be liberated again from their ‘liberators.’”

Later that morning, Bruty was finally cleared by the 25th Regiment in conjunction with troops of the 211th VGD who had advanced on the right flank of the HJ and entered the village from the south. Eighty prisoners were taken and a large number of antitank guns and mortars, two undamaged T-34s, and six large caliber howitzers were found in the area. Bruty was in German hands, but the cost had been high—particularly in the 25th Regiment.

In the meantime, in preparation for the assault on Kamenin, elements of KG Peiper had secured the road junction immediately north of Kamenny Most.

The I SS Panzer Corps spent February 23 preparing for its final assaults on Kamenin and Bina. The Leibstandarte, with elements of the 46th Infantry Division, was to attack the former, and the Hitlerjugend, still with support from the 211th VGD, was to secure Bina and its bridge across the Gran. Intelligence sources indicated that there were elements of two motorized mechanized brigades still in the bridgehead. H-hour was set for 0200 hours on the 24th.

In the HJ sector the most bitter fighting occurred in the area of the railway line which runs north-south just to the west of Bina. This had been heavily fortified, as had some of the flood dikes, but by using the main Kvetna-Bina road as their axis and taking advantage of the gently sloping ground, which dropped some 30 meters down to the village, the tanks and SS Panzergrenadiers soon overcame all resistance. By 0830 hours the village had fallen. The last Russians blew the Gran bridge as they withdrew.

In the southern part of the bridgehead, elements of the 46th Infantry Division moved on Kamenin from the west, while the LAH attacked from due south. The Mk IVs, Panthers, and Tigers of KG Peiper used the main road as their axis and soon encountered a screen of 37 antitank guns sited on the dominating ground to the south of the village. Nevertheless, the attack was pressed home without regard to possible casualties, and the sheer power of the armored assault was too much for the Russians, who abandoned their guns and fled. Panzergrenadiers followed up, and after some bitter house-to-house fighting the defense was broken. By late afternoon, the Gran bridgehead had been eliminated.

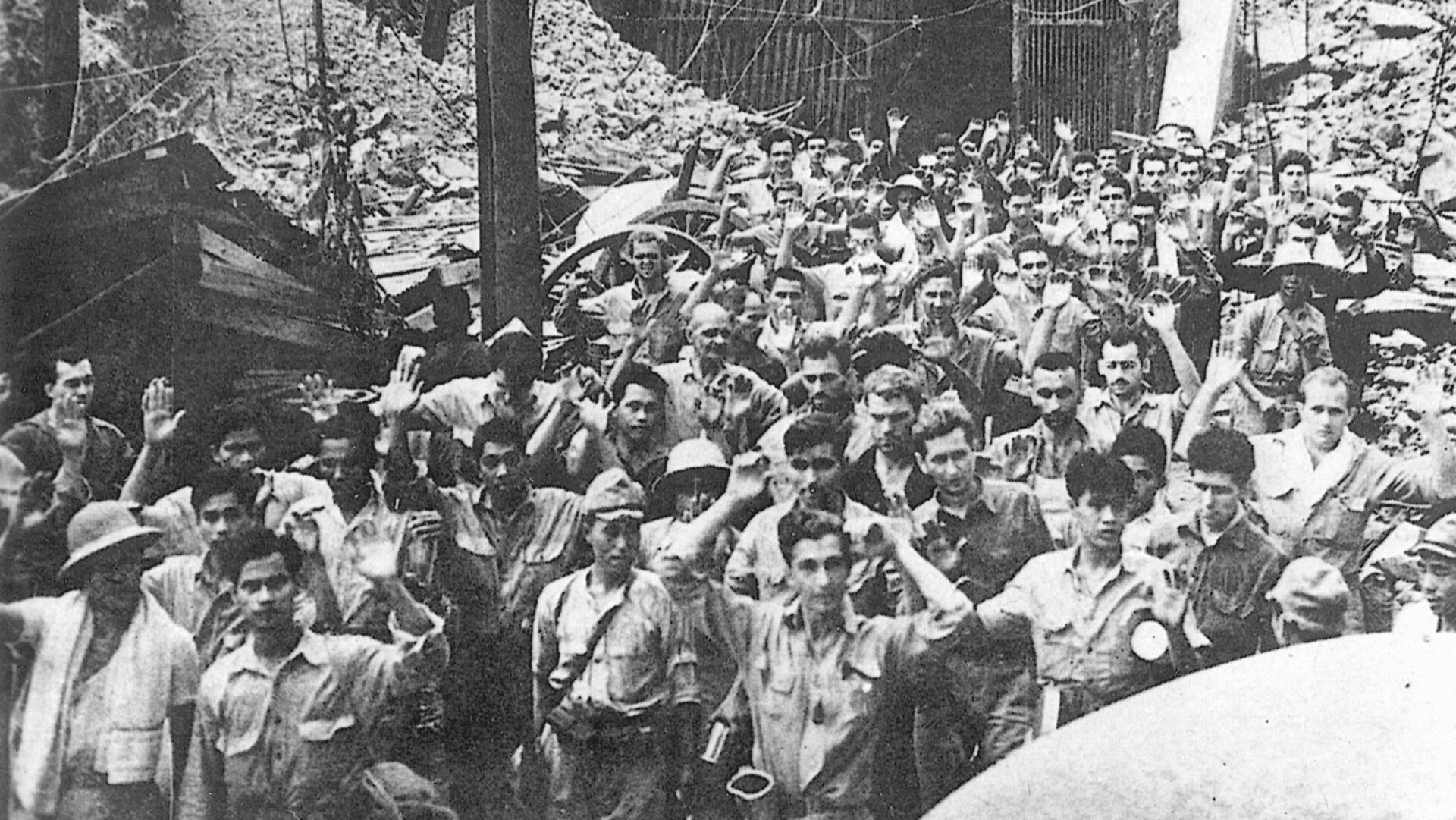

The Germans claimed 71 tanks; 179 guns, howitzers, and antitank guns; 537 prisoners; and 2,069 Russian dead in the fighting upto February 22. Of these, Peiper credits Werner Poetschke’s mixed SS Panzer Battalion with 23 T-34s destroyed; 30 Hungarian, Italian-, British-, and German-built tanks captured, and 280 enemy killed. According to a return signed by Fritz Kraemer, the chief of staff of the Sixth Panzer Army, I SS Panzer Corps suffered 2,989 casualties, including 413 killed in the same period and, rather surprisingly, only three Mk IVs, six Panthers, and two Tigers lost or in need of long-term repair. Figures quoted in the histories of the LAH and HJ would indicate that this is a major understatement.

Operation South Wind was, without doubt, a brilliant success. In eight days, I SS Panzer Corps, admittedly with valuable assistance from Panzer Corps Feldherrnhalle, had recaptured over 400 square kilometers of territory, inflicted 8,800 casualties on the Red Army, and cleared seven infantry divisions and a guards mechanized corps from west of the Gran. It is remarkable that such an effective fighting machine could have been produced within a month of the Battle of the Bulge disaster, and it is even more so when one takes into account that many of men involved had received only minimal training.

As Otto Kumm described the Leibstandarte, “The Division was in miserable shape, only a shadow of its former self. After the heavy losses in Normandy and during the Ardennes offensive, it had only recently been refitted with personnel who were poorly trained former members of the Army, Navy, Air Force, labor service and police.”

The performance of both the LAH and the HJ in South Wind can be explained only by superb leadership, high morale and fighting spirit, and a brilliant reinforcement and replacement system. That said, the question arises as to whether this elite SS panzer corps should have been used in this operation at all.

Despite all the measures taken to disguise the arrival of the Sixth Panzer Army on the Hungarian front, units of I SS Panzer Corps were soon detected in the Gran bridgehead operation. Its commitment there, rather than in the northern part of the Eastern Front, and the knowledge that a second SS Panzer Corps had arrived in Hungary, immediately alerted the Soviets to the possibility of a German offensive. It is also obvious that the premature use of the corps interrupted the proper refitting of the two SS panzer divisions and, indeed, actually ensured that their effectiveness in Operation Spring Awakening would be reduced.

Taken together, these facts indicate that the use of I SS Panzer Corps in Operation South Wind was a serious mistake. The chief operations officer of the Sixth Panzer Army, SS Lt. Col. Georg Maier, expressed similar thoughts in his book Drama Between Budapest and Vienna, published in 1975.