By Joseph Frantiska, Jr.

From the time of the Wright brothers, the vast majority of aircraft were biplanes with two wings stacked one above the other. The low-powered engines of the day dictated that the structure be as strong but also as light as possible. The stress and structural integrity would be accommodated by a series of struts and wires. With a virtual forest of struts and wires, the biplane created a lot of drag.

The solution seemed to be a single-wing or “monoplane” configuration, made possible by more powerful engines that could support heavier structures. But how to create a strong monoplane structure?

The answer was the cantilevered, or self-supporting, wing, with all of the supporting members within itself to take the place of the external struts and wires of the biplane configuration. A single large structural element called the main spar runs through the entire wing span, designed to handle this stress by spreading it through the fuselage from one wing tip to the other. To resist these forces, a secondary smaller member called a drag spar is located at a distance behind the main spar.

All of these technological advances brought the day of the carrier biplane fighter to an end. In 1935, the Navy issued a request for proposal to design and build a monoplane fighter to replace the Grumman F3F biplane fighter.

The XF4F-2 was an all-metal monoplane with a cantilever mid-wing weighing 5,535 lbs. Cutting-edge technologies included the NACA 230 airfoil with a maximum speed of 290 mph, a 1,050 hp. Pratt & Whitney R-1830-66 Twin Wasp radial with a single-stage supercharger, and a Hamilton Standard constant-speed propeller.

However, not all aspects of the new fighter were state-of-the-art; the landing gear was lowered or raised by 30 turns of a hand crank. A significant amount of pressure and torque could cause a serious hand injury if one were not careful.

Armament was two .30-caliber machine guns in the fuselage and provisions for two .50-caliber guns in the wings, or one 100-lb. bomb under each wing.

The XF4F-2’s first flight was on September 2, 1937, with Grumman test pilot Robert Hall at the controls. In April 1938, it was flown to the Naval Air Factory in Philadelphia for evaluation. On April 11, the XF4F-2 was undergoing a simulated carrier deck landing when engine failure caused the pilot to make a forced landing in a farm field, which flipped the aircraft onto its back. The pilot was not seriously hurt, but the aircraft had serious damage and was sent back to the factory for repairs.

But the XF4F-2 showed enough promise not to be rejected completely. Grumman used the same fuselage form and landing gear as it developed a new prototype, which was designated the XF4F-3. The fuselage was lengthened as were the wings, which received squared-off tips to improve maneuverability. The wing area was increased, the tail section was redesigned, and the gross weight increased by 600 lb. It was powered by a 1,200 hp. Pratt & Whitney XR-1830-76 radial engine with a two-stage, two-speed supercharger driving a Curtiss Electric propeller.

The first flight was on February 12, 1939, achieving a speed of 333.5 mph at 21,300 feet. Thus, the Navy primary requirement of a 300 mph maximum speed was accomplished. The Navy awarded Grumman a production contract on August 8, 1939, for 54 “Wildcats,” as they were dubbed, with the first to be delivered in February 1940.

Several test pilots who flew the Wildcat found it to be a formidable aircraft, despite criticism for its small size and lack of agility. British test pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown and U.S. Navy/Grumman test pilot Corwin “Corky” Meyer weighed in on the Wildcat’s personality in the air: “The design of any combat aircraft involves a measure of compromise and that of the shipboard single-seat fighter perhaps more than most as its success depends particularly heavily on the right balance being struck between the demands of combat and the dictates of the venue in which it is to spend its entire working life.

“A masterpiece in coalescence of the contradictory factors called for in a fighter suited to the naval environment was, in my view, the corpulent but rugged and pugnacious little warplane…which was to establish Grumman’s famed genus Felis.”

About the manual landing-gear retraction system, Corwin “Corky” Meyer had this to say: “It was simple in design, but its operation left a lot to be desired. The crank handle was located on the right side of the cockpit. Thus, the pilot had to remove his left hand from the throttle (and sincerely hope that he had tightened the throttle friction knob before takeoff), grab the control stick, and use his now-free right hand to actuate the landing gear lever to the ‘retract’ position and then complete the strenuous cranking task of 31 turns to raise the gear.”

Production F4F-3s removed the .30-caliber fuselage guns and used four .50-caliber machine guns in the wings with the horizontal stabilizer set higher on the tail. The third and fourth production F4F-3s were fitted with the 1,200 hp. Wright Cyclone R-1820-40 engine and designated the XF4F-5.

The fifth and eighth production F4F-3s were given armor protection and reinforced landing gear. Some early F4F-3s were fitted with automatically deployed flotation bags on the wings in case of a ditching. The idea worked when, on May 17, 1941, Ensign H. E. Tennes of the USS Enterprise’s VF-6 ditched his F4F-3 into San Diego Bay due to landing-gear failure. Shortly thereafter, the flotation system was deleted to save weight, and it was thought that a floating aircraft in a combat area could just as easily be recovered by the enemy.

The Navy was concerned that there might not be enough carriers or land bases to operate its aircraft from in the Pacific Theater. One F4F-3 was fitted with twin “Edo” floats and called the F4F-3S “Wildcatfish.” Its first flight took place on February 28, 1943, piloted by Grumman test pilot F. T. Kurt.

As the war progressed, American industry could more than keep up with the need for carriers, and the Navy Seabee construction battalions could transform jungle into airstrips at a rapid pace. The purpose for the F4F-3S vanished, and with it so did any further development beyond the prototype.

The advances made on the F4F-3 made it attractive to America’s allies, so in 1939, France placed an order for 81 export versions designated as G36As. It differed from the standard F4F-3 in that it was powered by a 1,200 hp Wright R-1820-G205A-2 Cyclone engine, with a single-speed, two-stage supercharger.

The French G-36A version required six wing-mounted 7.5mm Darne machine guns with an OPL 38 gunsight, Radio-Industrie-537 communication equipment, instrumentation based on the metric system, and a throttle that operated in reverse of that of U.S. aircraft.

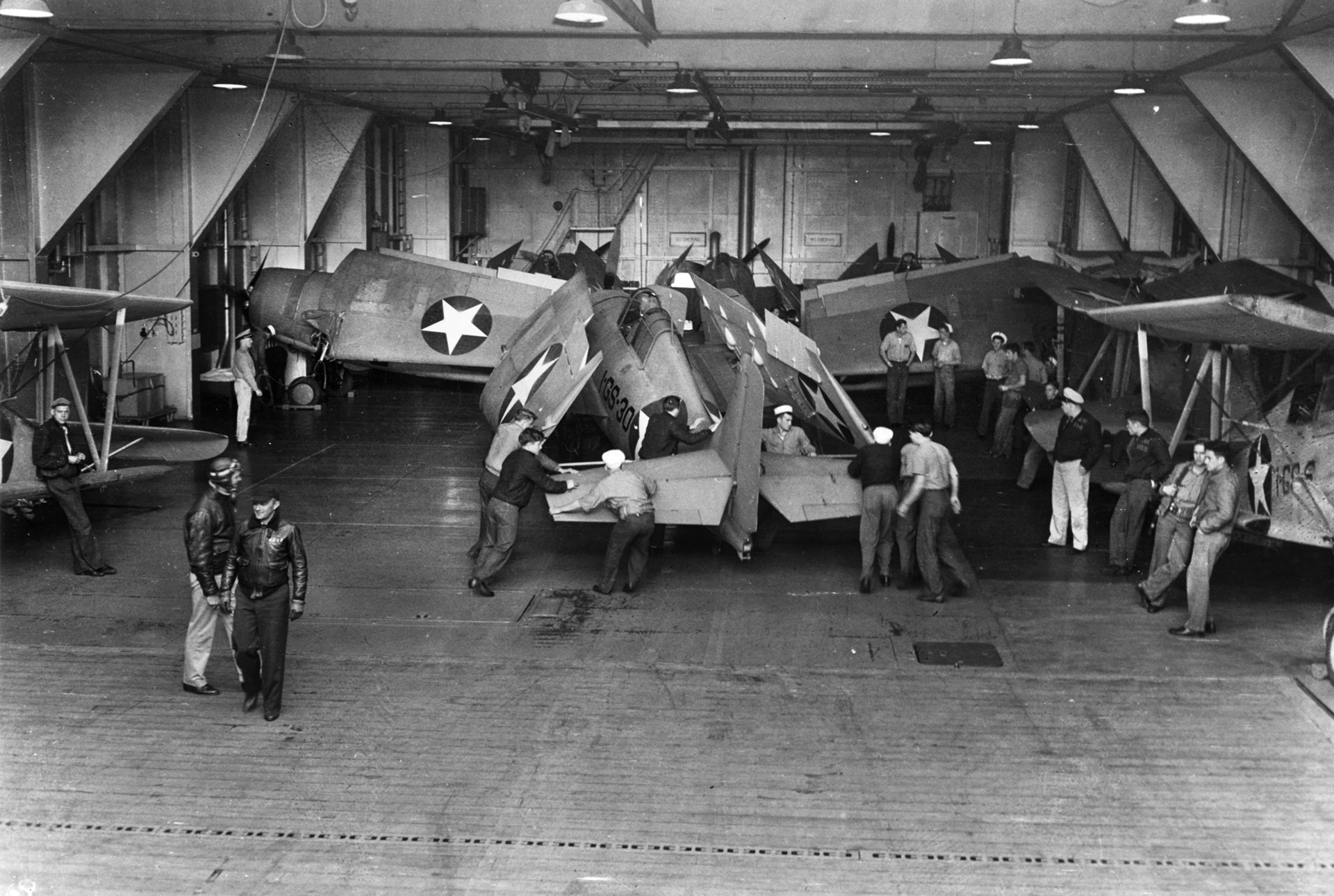

Folding wings were necessary to stow as many aircraft as possible in the limited hanger deck space on a carrier. The F4F-4 was the first Wildcat to feature a Grumman folding-wing innovation known as the “Sto-Wing.”

Most folding-wing naval aircraft of the time were able to fold their wings via a simple hinge point outboard of the landing gear. However, the Sto-Wing used a compound angle approach that was unique to Grumman aircraft.

The brilliant Leroy Grumman developed the idea by experimenting with a rubber eraser in place of a fuselage and a paperclip in the place of a wing. Attaching the paperclip into the side of the eraser as a wing attached to a fuselage, through trial and error he found the angle where the wing would fold flat against the fuselage. It was so successful that it was later used on Grumman’s F6F Hellcat fighter and TBF Avenger torpedo bomber.

In 1942, Grumman was a busy place, as the company was building not only the Wildcat but the TBF Avenger torpedo bomber, as well as the J2F Duck and J4F Widgeon amphibians. The production capability reached a tipping point when Grumman decided to focus their fighter efforts on the Wildcat’s successor: the more powerful and lethal F6F Hellcat.

The Wildcat’s production was transferred under contract to General Motor’s Eastern Aircraft Division in Linden, New Jersey. The contract called for 1,800 F4F-4s, which were designated the FM-1 (F= fighter, M=General Motors). Of the entire production order, 311 aircraft were delivered to Britain as the Martlet V.

In comparison to the F4F-4, the FM-1 had four .50-caliber wing-mounted guns. A total of 839 FM-1s were delivered to the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps by late 1943 before production was halted in favor of the lighter FM-2.

The F4F-7 was a long-range photographic reconnaissance version with a total fuel capacity of to 695 gallons, with 555 gallons in non-folding wings filled with fuel tanks. This gave it the highest loaded weight of all Wildcats at 10,328 lbs. Missions as long as 25 hours and a maximum range of 3,700 miles were possible. Such long flights could be taxing on the pilot, so a Sperry Mark IV automatic pilot was installed.

To aid in pilot visibility, it was fitted with a rounded Plexiglas windscreen, which was put to good use shortly after the F4F-7s initial flight on December 30, 1941, when the Bureau of Aeronautics’ Lt. Cmdr. Andy Jackson flew across the country in 11 hours at an average speed of 165 mph.

A Fairchild F-56 reconnaissance camera replaced the reserve tank and was placed just behind the main fuel tank. The camera was the only item that the pilot could “shoot” targets with, as there was no armament installed to save weight. Pilot armor was also not added as an additional weight-saving measure.

Such a large amount of fuel could pose a problem in a variety of situations, so two emergency fuel dump tubes were located under the rudder.

While orders for this type exceeded 100 units, only 20 were built, and these were converted to F4F-3s. Two F4F-7s were used by the 1st Marine Air Wing at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. After being destroyed in Japanese air raids, they were replaced by aircraft from Marine Observation Squadron 251 (VMO-251).

Total production of the Wildcat, excluding prototypes, was 7,898 aircraft, with 5,927 produced by General Motors. Production ended in August 1945 with the conclusion of the war in the Pacific.

The Wildcat’s first combat experience came in the Pacific, on December 8, 1941, the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, when Japanese forces attacked Wake Island. A squadron of 12 Wildcats from Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-211 were based on Wake, with four airborne on patrol duty. Due to poor weather, they failed to intercept the 36 Mitsubishi G3M bombers that attacked the airfield on Wake, destroying seven of the eight Wildcats on the ground.

The Wildcat had its revenge three days later, when Japanese ground troops disembarked from ships to invade Wake. Four Wildcats attacked the invasion fleet and aided in sinking a destroyer and forcing the fleet back to sea. When the Japanese force returned on December 22, only two Wildcats were still flying. Wake fell to the Japanese the next day.

The Battle of Midway would be a somewhat more impressive experience for the Wildcat, as its lack of maneuverability against the agile Japanese aircraft was countered by employing an innovative tactic called the “Thach Weave.”

The Thach Weave was an aerial combat tactic developed by U.S. Navy pilot John S. “Jimmy” Thach and named by fellow aviator James H. Flatley soon after the United States entered World War II.

Thach had read an intelligence report published in the September 22, 1941, Fleet Air Tactical Unit Intelligence Bulletin about the Japanese Zero’s amazing agility and climb rate. He commenced to develop tactics to give the slower and less-agile Wildcats an advantage in combat. He developed what he called “Beam Defense Position,” which would become known as the Thach Weave.

It was executed either by two fighter aircraft or by two pairs of fighters in formation. When an enemy selected one fighter as his target (the “bait”), the two elements turned in towards one another. With one aircraft crossing behind the other, they waited to have adequate distance from one another and repeated the crossing maneuver in a weaving fashion. This would bring the enemy aircraft in front of the other element, called the “hook,” which would then fire on the enemy. Positioning was valued over maneuverability. Thach asked Ensign Edward “Butch” O’Hare, the leader of the second section in Thach’s division, to test the idea.

In the test, Wildcats were used as both the enemy aircraft and pairs of “bait” and “hook” aircraft. Thach took off with three other Wildcats as the bait/hook aircraft as O’Hare led four Wildcats in the role of “enemy” aircraft. The bait/hook aircraft had their throttles’ travel restricted to reduce their performance, while the “enemy” aircraft had their throttles unrestricted to create superior performance as in the Zero fighters.

After a series of “attacks,” in every situation Thach’s fighters had either thwarted the attack or got into a position to return fire. O’Hare excitedly commended Thach, “Skipper, it really worked. I couldn’t make any attack without seeing the nose of one of your airplanes pointed at me.”

The first combat test of the tactic was during the Battle of Midway in June 1942, when a squadron of Zeroes attacked Thach’s flight of four Wildcats. Thach’s wingman, Ensign R. Dibb, was the “bait,” and when he was attacked, he turned towards Thach. Thach, in turn, dove under Dibb, firing at the incoming Zero’s underside until its engine was ablaze.

The maneuver soon found its way into the repertoire of U.S. Navy and U.S. Army Air Corps pilots. Marine Wildcat pilots flying out of Henderson Field on Guadalcanal also adopted the tactic.

Celebrated Japanese ace Saburō Sakai described his reaction and that of his fellow pilots when they encountered the Guadalcanal Wildcats using it: “For the first time Lt. Cmdr. Tadashi Nakajima encountered what was to become a famous double-team maneuver on the part of the enemy. Two Wildcats jumped on the commander’s plane. He had no trouble in getting on the tail of an enemy fighter, but never had a chance to fire before the Grumman’s teammate roared at him from the side. Nakajima was raging when he got back to Rabaul; he had been forced to dive and run for safety.”

There were many U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps pilots who became aces in the Wildcat, and they all deserve respect for their gallantry and service. But the exploits of four earned them America’s highest award for valor: the Medal of Honor.

Being a one-man air force was a trait common among a number of pilots who received the MoH, and Wildcat pilot 1st Lt. James Elms Swett was one of them.

Swett was a USMC fighter pilot and was awarded America’s highest military decoration for actions with VMF-221 over Guadalcanal on April 7, 1943. His first combat mission was as leader of a formation of four Wildcats on a combat air patrol over the Russell Islands in the Solomon Islands on April 7, 1943, in anticipation of a large air attack; they were scrambled as 150 Japanese aircraft were reported approaching Ironbottom Sound. Sighting a large formation of Japanese Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers attacking Tulagi harbor, the fight began.

Swett pounced on three Vals that were diving on the harbor and shot down two. As he was evading the fire of the third Val’s rear gunner, his plane’s left wing was hit by friendly ground fire. He persevered and downed the third Val as he turned toward a second formation of six more Vals.

He repeatedly dove on the formation, downing one Val in each attack with short bursts of his machine guns. After splashing four Vals, he began attacking a fifth when his ammunition was exhausted. The 22-year-old Marine pilot from Seattle, Washington, had performed the extremely rare feat of becoming an ace on his first combat mission, with seven kills—a feat for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Wounded after being hit by enemy fighters, Swett’s ditched his damaged fighter off Florida Island after his oil cooler had been hit, causing his engine to seize; he crashed into the waters of Tulagi harbor.

With his nose broken and his face bleeding from broken Plexiglass, Swett went underwater with his plane but managed to release his harness and bob to the surface. When a Coast Guard boat approached, a crewman shouted, “Are you an American?”

“Damn right I am!” Swett shouted back.

After being patched up, he would get back in the war. In July 1943, flying a Corsair, Swett was shot down by a Japanese Zero near the island of New Georgia and was rescued by two natives in a canoe.

He later flew from the aircraft carrier Bunker Hill and carried out strikes supporting the Iwo Jima and Okinawa invasions in 1945. He flew a total of 103 missions, was credited with downing 16 Japanese planes and sharing in the destruction of one more, and had another nine “probables” shot down by war’s end.

Swett survived the war and died in 2009 at the age of 88.

A final tribute to the ruggedness of the Wildcat came from Saburo Sakai, who recalled an encounter with the American plane: “I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7mm machine guns. I turned the 20mm cannon switch to the ‘off’ position, and closed in.

“For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying. I thought this very odd—it had never happened before—and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman.

“To my surprise, the Grumman’s rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now.”

Tough, rugged, and it could give a punch as well as take one—the kitten definitely had claws.