By Patrick J. Chaisson

The chief shuffled to his seat in the underground conference room. He sat down heavily, eyes unfocused and dreamy, while a litany of woes was read to him. His military had sustained well over one million casualties in the past three months. Strong enemy forces were pushing against his country’s frontiers from all directions. And there seemed to be little the poorly equipped and disorganized remnants of his army could do to stop them.

There was more bad news. In their latest headlong retreat, the chief’s soldiers had left completely unguarded a key border zone. Well known to all present as a traditional invasion route, this heavily wooded region was called the Ardennes.

Upon hearing the word “Ardennes,” the chief abruptly raised his hand for silence. A long pause followed. Finally, he stood up and, eyes ablaze, announced in a firm voice: “I have made a momentous decision. I shall go over on the offensive, that is to say here,” he stabbed at a map, “out of the Ardennes—with the objective Antwerp!”

Adolf Hitler’s proclamation, made in his East Prussian command post on September 16, 1944, was indeed a momentous event. It led directly to Nazi Germany’s last great strategic gamble in the West, an operation popularly labeled “The Battle of the Bulge” by generations of writers. For many, the words Hitler spoke that day serve to mark the campaign’s starting point.

Yet, as U.S. Army historian Hugh M. Cole observes, it is unrealistic to believe this colossal encounter was fought “because the Führer had placed his finger on a map and made a pronouncement.” The story of Hitler’s high-stakes decision to risk the very existence of Germany on a desperate winter struggle is a fascinating glimpse into the Third Reich’s military, political, and economic circumstances during the second half of 1944.

Understanding the Ardennes offensive also requires an exploration into the mind of the man who conceived this operation, dictated its time, place, and objective, and later involved himself in virtually every detail of its execution. This man was Chancellor of Germany and supreme commander of her armed forces: Adolf Hitler.

His challenges in mounting this attack were many. Five years of war had taken an alarming human toll on the Reich. Some 3,750,000 of Germany’s best soldiers had already been killed, captured, wounded, or gone missing, and while 10 million men and women still wore its uniform the combat effectiveness of those remaining diminished with every military setback.

Setbacks there were, and in 1944 these came at a dizzying speed. During June and July the Red Army ripped a hole 100 miles wide and 200 miles deep into Hitler’s Ukrainian front. This summer offensive—codenamed Operation Bagration—resulted in the annihilation of his 9th, 4th, and 3rd Panzer Armies along with 500,000 Wehrmacht soldiers.

The Soviets struck again in August, this time along the Danube River in Romania. Within two weeks Russian armies obliterated another 16 German divisions while inflicting 380,000 casualties. This calamity prompted the Romanian government on August 23 to switch sides—the first of several such defections the Third Reich would suffer that season.

Next to abandon Germany was Bulgaria, quitting the Axis camp on September 8. As a result the Wehrmacht, its flank no longer tenable, evacuated Greece. Still worse, all Nazi forces were made to leave Finland after September 15, when that nation signed an armistice with the Soviet Union.

Aside from whatever military support these former allies were no longer providing Germany, the loss of their raw materials severely hampered the Reich’s war production effort. Gone were Ukrainian manganese, Yugoslavian copper, Finnish nickel, Belgian steel, and French bauxite. Supplies of Turkish chrome, Spanish tungsten, and Swedish iron ore became increasingly uncertain as these neutral powers began to reevaluate their relationships with Hitler’s regime.

Most troubling to Albert Speer, Germany’s brilliant head of war production, was the forfeiture of Romania’s oil fields. A modern, mechanized army could not fight without petroleum, and the Luftwaffe—Hitler’s once feared air force—was now mostly grounded due to fuel shortages. In September Speer advised his Führer that the Reich had stockpiled raw materials sufficient for just one more year of war, providing no more territory was lost.

By this point, however, Germany was surrendering territory on almost every front. After successfully assaulting the Normandy coast on June 6, British, Canadian, and American armies began pouring onto the European continent. During July and August, the Western Allies broke clear of their beachheads and began a rapid advance across France and Belgium. Paris was liberated by August 25, Brussels nine days later, and the port of Antwerp fell on September 4.

After Allied troops moving out of Normandy linked up with another invasion force from southern France, the Wehrmacht could no longer offer a coherent defense against them. With most of their equipment destroyed, thousands of desperate soldiers began streaming east toward Germany. The collapse in France was both sudden and total.

It was an utter disaster for Hitler’s legions in the West. From Holland, across Belgium, and down to the Swiss border, there remained almost no organized force able to combat the rampaging Anglo-Americans. Seemingly all the Western Allies had to do was make one final push directly into the heart of an unprotected Germany and end the war.

Any national leader, when faced with military threats such as these, would have good cause for concern. Adolf Hitler, however, remained unworried, even confident in the face of catastrophe on both the Eastern and Western Fronts during the first weeks of September 1944. This was partially due to the Führer’s unbridled optimism and confidence in Germany and her people. Another important factor was his belief in the force of will, notably his own.

As Hitler himself explained that summer, “My task has been to never lose my nerve under any circumstances…. I live for the single task of leading this struggle because I know if there is not a man who by his very nature has a will of iron, then the struggle cannot be won.”

The Führer’s willpower was sorely tested when assassins detonated a bomb in his East Prussia headquarters, named the Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair), shortly after noon on July 20. While the explosion failed to kill its intended target, Hitler did sustain significant physical and psychological injuries. He was partially deafened, his right eardrum perforated and bleeding. Inner ear trouble affected Hitler’s balance; for months he exhibited signs of vertigo. A lacerated right arm stubbornly refused to heal.

Whether due to the bomb blast or his own unhealthy lifestyle, Hitler began complaining of stomach cramps, occasionally so severe he could not function normally. He also experienced insomnia, sinus headaches, and an uncontrollable shaking in his extremities. During the course of six days in mid-September, he suffered three minor coronary episodes—one occurring just hours before the meeting in which he announced his decision to attack out of the Ardennes.

The assassination attempt affected him mentally as well. Hitler’s paranoia increased—all his food had to be tasted before he would eat it, and visitors to the Wolfsschanze were searched for hidden weapons before being allowed to enter. No one, not even the Führer’s closest advisers, could bring a briefcase or sidearm inside his headquarters complex.

Growing increasingly mistrustful of his generals, some of whom were behind the bomb plot, he now saw disloyalty in any act other than unquestioning obedience. Hitler had long believed that only he could save Germany from its enemies; now he was sure of it. “After my miraculous escape from death today,” he informed a visiting Benito Mussolini that evening, “I am more than ever convinced that it is my fate to bring this [war] to a triumphant conclusion.”

Hitler also regarded himself as a strategic genius. Early luck supported this delusion; in the Führer’s mind all of Germany’s recent military defeats were attributable to traitorous Army officers who had deliberately thwarted his brilliant operational plans. Increasingly it was Hitler’s intuition, not sound military strategy, that directed the Reich’s war effort.

After July 20, Nazi officials began involving themselves with martial matters. Immediately following the assassination attempt SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler got himself named commander of the Replacement Army, or Ersatzheer. Already heading most of Germany’s internal security agencies, Himmler now oversaw its means of raising new military forces. Other political chieftains, notably Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and Party Secretary Martin Bormann, started attending daily situation conferences in the Wolfsschanze as a means of furthering their own agendas.

Hitler did keep within his inner circle several members of the armed forces who still retained his confidence. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel continued to serve as chief of the Führer’s Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), or supreme military headquarters. It was largely a symbolic post. There was no doubt that Adolf Hitler really ran things, whereas Keitel merely carried out his chief’s bidding.

In fact, Keitel’s haughty, authoritarian manner masked a weak-minded bureaucrat, ever eager to win his Führer’s approval. So transparent was the field marshal’s toadying that other members of Hitler’s staff secretly called him “Lakeitel,” a play on his name that means “lackey.”

Far more able was Colonel General Alfred Jodl, head of OKW’s operations division. Dour, taciturn, yet totally devoted to his Führer, Jodl’s unenviable task was to transform Hitler’s rambling, often incoherent directives into proper military orders. Surprisingly, these two worked well together.

As a member of Adolf Hitler’s immediate entourage, Jodl was never far from the chief. During the summer of 1944, this meant living and working in a steel-reinforced bunker complex near Gorlitz, East Prussia. Jodl despised the Wolfsschanze, calling it a combination monastery and concentration camp, while his work schedule—tied to the Führer’s odd sleep habits—could not have been less productive.

A typical day for Hitler began no earlier than 11 am. After waking and dressing, he then met Jodl for a private briefing in his subterranean quarters. This was followed at 1 pm by the daily military conference, which could last for hours. Then he ate a vegetarian meal, took a siesta, and went straight into the evening’s situation update. Often with Jodl by his side, the Führer normally worked straight through the night before returning to bed at 5 am.

It had been months since Hitler had seen any region of Germany apart from his isolated military headquarters in East Prussia or the relatively unscathed Bavarian resort town of Berchtesgaden. The charismatic leader who once enthralled thousands of loyal Germans with his rallies and speeches had almost completely cut himself off from the public. All he knew of the Third Reich’s military situation was what his few trusted advisers told him—and thesejaleute(yes-people) knew what fate awaited staff officers who brought their Führer unpleasant news.

By the late summer of 1944, those nearest him quietly began to question Hitler’s sanity, noting how after July’s assassination attempt his decisions were becoming increasingly erratic. “He lost himself more and more in a world of theories which had no basis in reality,” said General Heinz Guderian, in charge of the war against Russia. And General Walter Warlimont, Jodl’s deputy on the operations staff, added, “It seemed as if the shock [of the blast] had brought into the open all the evil of his nature, both physical and psychological.”

Despite his mental decline, Hitler recognized that only a political solution to the current crisis would bring lasting peace for Germany. His generals thought in operational terms; their perspective extended only as far as the success or failure of their next military campaign. The Führer, however, sought to impose his will on the alliance of nations joined against him. But which of his admittedly formidable adversaries could, with a battlefield defeat, be forced to leave the war?

Although American President Franklin D. Roosevelt had declared the Allies would accept nothing short of Germany’s unconditional surrender, Hitler in mid-1944 began to perceive cracks in the Western coalition. From various sources, his intelligence analysts learned of growing friction between Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower and his generals as they competed for increasingly scarce resources during the drive across France and Belgium. Sensing an opportunity, the Führer instructed his propaganda minister, Goebbels, to exploit these perceived fissures between the British, Canadian, and American partners.

Goebbels also initiated several public relations programs he hoped would “awaken the German people to the approaching peril.” A mandatory 60-hour work week took effect while industry deemed not essential to the war effort was closed down. Government officials also shuttered all theaters and universities. Providing much of the muscle that shifted Germany’s economy into high gear were seven million prisoners and foreign workers—one fourth of the nation’s labor force—toiling in mines, factories, and farms.

Despite enduring a strategic bombing campaign that terrorized the populace and led to severe shortages in medicine, synthetic rubber, and petroleum, German war production actually reached its peak output (except in oil and aircraft) during the summer of 1944. These numbers seemed reassuring, but would they be enough to replace combat losses as well as to outfit the new formations that Hitler was demanding?

Himmler, recently appointed as head of the Replacement Army, was ordered to raise 25 new Volksgrenadier (People’s Infantry) divisions, a new type of organization in which significantly increased firepower was intended to compensate for lower troop strengths. He ruthlessly combed out rear-area garrisons, as well as prisons and hospitals, to find men for these formations.

All healthy German males aged 16 to 60 were now eligible for conscription, while the service exemptions once enjoyed by high-ranking Nazi families had mostly evaporated. By mid-August, Himmler’s efforts produced 450,000 new soldiers (many of whom actually came from the Luftwaffe or Kriegsmarine), with another 250,000 in the process of being trained.

These achievements, briefed to Hitler by his coterie of Nazi advisers, certainly inspired in him a measure of hope. More good news reached the Wolfsschanze during early September when OKW reported a curious “deceleration” in the Western Allies’ advance. Quite literally the British and American armies had run out of gas—in some cases within sight of the German frontier. This logistical crisis, coupled with a similar quiet in the East, allowed Germany the briefest of respites to organize and reconstitute its forces.

Hitler now had breathing room, a chance to develop the concept he believed would split the Allied coalition and win victory in the West. Once free to focus solely on the Eastern Front, a resurgent Wehrmacht—aided by new wonder weapons then in development—could in Hitler’s mind easily regain the initiative against Russian forces.

The first evidence of the strategic vision that would eventually culminate in Hitler’s Ardennes offensive dates back to November 1943. In a staff conference, the Führer declared the West was his decisive theater of operations. He said the overall situation would change little if his armies destroyed 30 of the Red Army’s 500 divisions, but should the Wehrmacht wreck 30 British or American divisions—one third of their eventual combat power in Europe—the Western Allies were certain to sue for peace on Germany’s terms.

Hitler amplified this view during a situation briefing held on July 31, 1944. Opening with an acknowledgement of the threats now looming on all fronts, he recognized that Wehrmacht forces might eventually have to abandon France. The Führer also confessed that it was at present impossible to combat Anglo-American supremacy in the air. Germany needed time, he claimed, to form new panzer divisions and jet fighter squadrons.

Afterward, Hitler kept Jodl and Warlimont back for a private conference. In a long monologue he more fully explained his idea of a climactic battle fought against the Western Allies in which Germany’s destiny would be decided. He next directed Jodl to form a small planning cell charged with examining options for such a counterattack in the West, further requiring all present to maintain absolute secrecy.

This initial guidance was admittedly broad. During the following weeks, however, more definitive directives began to appear. Meeting with his military advisers and Production Minister Speer on August 19, the Führer ordered that a force of 25 new divisions be assembled for a decisive blow in the West. This campaign was to occur during November or December, when bad weather would negate Allied air superiority.

A few weeks later, on August 31, Hitler again addressed the scope of his strategic objectives. “We shall continue this fight,” he vowed, “until—as Frederick the Great said—one of our accursed enemies becomes too weak to fight on.” The Führer continued, “There will be moments in which the tension between the Allies will become so great the break will happen. Coalitions in world history have always been ruined at some point.”

“The time is not ripe for a political solution,” he then cautioned. “To hope for a favorable political moment to do something during a time of severe military defeats is naturally childish and naïve. Such moments can present themselves only when you have successes.”

Over the next several weeks Hitler met frequently with his chief military planner, Alfred Jodl, to outline the operation. Together they pored over maps while discussing the attack’s timing, direction, breadth, and depth. Finally, on September 16, the Führer was ready to reveal his momentous decision. Accompanying Hitler in his stuffy conference room were Keitel, Jodl, Guderian, SS Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein (Himmler’s liaison officer), General Walther Buhle of the OKW, Ambassador Walther Hewel (chief diplomatic representative), and acting Luftwaffe chief of staff General Werner Kreipe.

It was a major strategic gathering. According to British military historian Peter Caddick-Adams, Hitler’s decision to announce his Ardennes offensive to this particular audience was a political gesture and not done for military reasons. The Führer needed to keep his grip on Germany, and this proclamation demonstrated to all present (the military, the diplomatic corps, and especially the SS) that he was still in control, that the war effort under his command retained direction and purpose.

Adolf Hitler further believed a stunning military victory would restore Germany to its former position of preeminence in world affairs. Such a triumph would also do much to maintain his personal hold on power. All that remained was to gather the forces necessary for a successful surprise attack.

First, a commander had to be found who could assemble and inspire the broken remnants of Hitler’s Western armies. This officer was Field Marshal Walther Model, nicknamed “The Führer’s Fireman” for his hard-driving ability to blunt enemy advances in the East. Model reported for duty on August 16, serving temporarily as Commander-in-Chief West as well as head of Army Group B.

Hitler then recalled the Reich’s “grand old soldier,” Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, from enforced retirement on September 1. The 68-year-old veteran dutifully accepted command of Oberbefelshaber (OB) West—a position from which he was fired in July—allowing Model to focus on tactical matters within Army Group B. Hitler hoped Rundstedt’s unsullied reputation with the troops and insistence on strict obedience would serve as a positive example to his forces in the West.

The Führer also began naming officers to command those armies leading his counterattack. On the same day he restored Rundstedt to duty as chief of OB West, Hitler promoted the scrappy Baron Freiherr Hasso von Manteuffel to General der Panzertruppen and named him as commander of the 5th Panzer Army. Two days later he placed General Erich Brandenberger in charge of the 7th Army.

The last army-level command change occurred on September 14, when SS-Oberst-Gruppenführer Josef “Sepp” Dietrich took over the 6th Army (renamed 6th Panzer Army on November 8). The selection of this well-connected but barely competent SS general to lead the 6th Army—spearhead of the entire Ardennes offensive —demonstrates how low the Führer’s stock in his army officer corps had fallen.

None of the men destined to carry out Hitler’s grand campaign in the West had any idea such an operation was being contemplated. Orders emanating from the distant Wolfsschanze merely directed them to begin rebuilding their formations with whatever means were available. Yet little could be obtained to replace what was lost in France; Wehrmacht High Command needed every new soldier, rifle, and tank for the 25 Volksgrenadier divisions on tap to lead the top-secret winter offensive then being planned.

It was a physically exhausted, careworn Adolf Hitler who on September 25 directed Jodl to draw up a formal directive for the Ardennes offensive. The members of his household entourage were shocked by their Führer’s appearance of late, commenting among themselves how aged, ill, and strained he now looked. That afternoon Hitler fell ill with jaundice and was confined to his bed for 10 days. Traudl Junge, Hitler’s 24-year-old private secretary, later wrote of her chief’s steady decline: “It was as if his body … had gone on strike.”

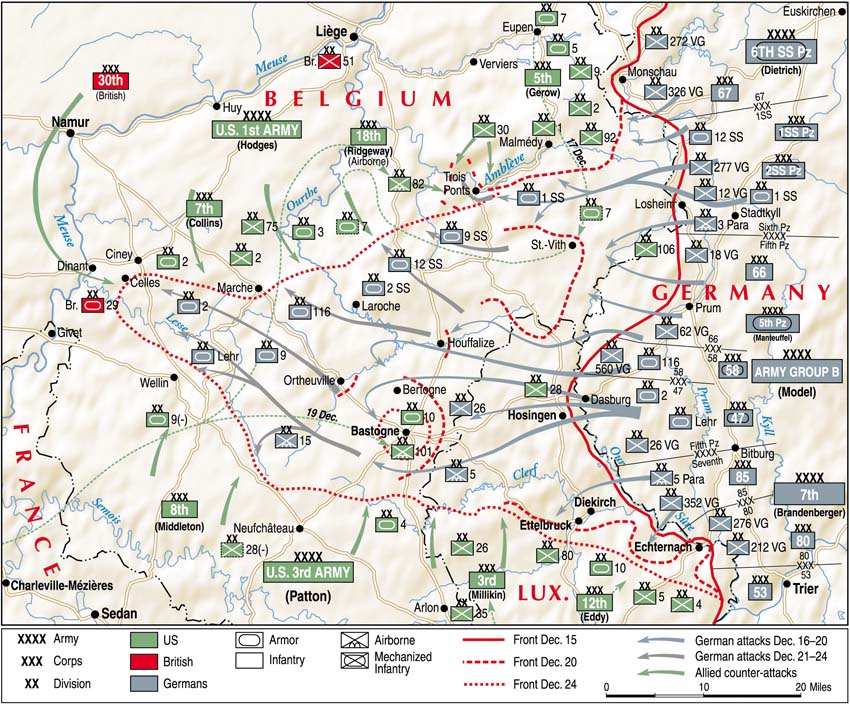

With their meddling Führer out of the picture for a while, Jodl’s planners quickly produced an operational outline. Its major points included a large-scale attack launching out of the Ardennes Forest sometime in late November 1944, with the initial object of seizing bridges over the Meuse River near Liege, Belgium. There would follow a battle designed to cut the British and Canadians off from their supply hubs, thus forcing an Allied evacuation of the Continent much in the manner of Dunkirk.

Jodl’s scheme further specified a massive pre-assault bombardment followed by three armies—two armored vanguards and an infantry formation providing flank security—advancing rapidly across a 60-mile front. Their final objective, 125 miles away, was the port of Antwerp. Success, Jodl postulated, would depend on bad flying weather to keep Allied air assets on the ground, total secrecy, and the Allies’ inability to react in time.

Two days later Jodl delivered to his chief the draft document, which he called Operation Christrose (Christmas Rose). Hitler instantly renamed it Wacht am Rhein, a bit of deception in case enemy spies caught wind of the scheme. His codename, translated as “Watch on the Rhine,” implied a defensive action, perhaps a reference to the West Wall, or Siegfried Line.

This chain of fortifications, recently refurbished by 211,000 civilian workers and slave laborers, represented the Wehrmacht’s main line of resistance in the West. Conventional military logic dictated a static defense behind the West Wall was Germany’s only possible response against fast-approaching Anglo-American forces. But by now the Third Reich’s high command was not guided by logic.

A revitalized Führer took Albert Speer aside on October 12 with news of his counterattack. After swearing the Armaments Minister to complete secrecy, Hitler demanded he raise a corps of construction engineers tasked with building bridges all through the rugged Ardennes. Dismissing Speer’s logistical concerns, the Führer remarked, “Everything else must be put aside for the sake of this, no matter what the consequences. This will be the great blow which must succeed.”

He fixed Speer with his glittering stare: “A single breakthrough on the Western Front!” Hitler exclaimed. “You’ll see! It will lead to collapse and panic among the Americans. We’ll drive right through their middle and take Antwerp. Then they’ll have lost their supply port. And a tremendous pocket will encircle the entire English Army, with hundreds of thousands of prisoners.”

Hitler then began initiating his field officers into the plan. Among the first to hear of Nazi Germany’s winter offensive was the Führer’s favorite commando, SS Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny. The tall Austrian got word of Wacht am Rhein directly from his commander in chief on October 21 when Hitler directed Skorzeny to raise a special operations unit called Panzer Brigade 150. Skorzeny’s men, many dressed and equipped as Americans, were to infiltrate the lines, seize key objectives, and spread panic throughout the U.S. rear area.

Reporting to the Wolfsschanze the next morning were Generals Siegfried Westphal and Hans Krebs, chiefs of staff to Rundstedt and Model, respectively. Neither knew why they had been summoned to supreme headquarters, their sense of dread increasing when each man was made to sign a secrecy oath threatening Sippenhaft—the punishment of family members—should he discuss what was about to be revealed.

Westphal and Krebs entered a meeting room where Hitler and Jodl briefed them in detail on the Ardennes campaign. They were also told to conserve as many forces in the West as possible for this attack, fighting all necessary defensive battles with a minimum number of troops. Then, before either officer could ask questions, the two were whisked away with instructions to inform their commanders of the mission.

When Wacht am Rhein was described to Rundstedt, he thought the idea “a stroke of genius” but realized Germany no longer possessed the means necessary to execute such a radical scheme. Calling the operation “a map fantasy,” he noted that “all, absolutely all conditions for the possible success of such an offensive were lacking.”

Model, for his part, reportedly thundered, “This plan doesn’t have a damned leg to stand on!” Yet orders were orders, and those officers charged with implementing the Führer’s Ardennes offensive immediately began making their own tactical preparations.

Rundstedt and Model met with the three commanders who would carry out Wacht am Rhein on October 27, when Manteuffel, Dietrich, and Brandenberger arrived at Model’s headquarters for a conference. During this gathering, which was held without Hitler’s knowledge, all present frankly discussed the operation’s failings: inadequate forces to accomplish the assigned mission, insufficient supplies, impossibly long flanks, a poor road network, and finally, no regard at all for the enemy’s response to German actions.

Sepp Dietrich, assigned to command the main effort, summed up his objections with typical dark humor: “All I had to do was to cross a river, capture Brussels, and then go on to take Antwerp. All this in the worst time of the year through the Ardennes where the snow is waist-deep and there wasn’t room to deploy four tanks abreast, let alone armored divisions. Where it doesn’t get light until eight and it’s dark again at four, and with reformed divisions made up chiefly of kids and sick old men. And all this at Christmas time!”

Both Rundstedt and Model, independent of one another, began to consider how Wacht am Rhein might be modified to contain more achievable goals. At the October 27 conference each officer presented his thoughts, which Model synthesized into one course of action labeled die kleine Lösung(the Small Solution). The field marshal’s staff packaged this alternative into a formal proposal, which was then submitted to OKW under the codename Herbstnebel (Autumn Mist).

Hitler’s headquarters ignored these recommendations, sending instead on November 2 another set of detailed instructions. Titled “Operation Wacht am Rhein—Order for Assembly and Concentration for Attack (Ardennes Offensive),” the directives contained a cover note that read, ”This plan is unalterable in every detail.”

Repeated protests from Rundstedt and Model failed to change their Führer’s mind on this issue. On November 10, Hitler signed the final operations order, which again made no mention of the Kleine Lösunghis field commanders were suggesting. Yet the generals refused to give up.

During a visit by Alfred Jodl to OB West on November 26, Rundstedt and Model once more pressed the Small Solution. Acknowledging their considerable combat experience while remaining obedient to his chief, Jodl admitted Wacht am Rhein was an extremely daring venture. “We were in a desperate situation,” he told them, “and the only way to save it was by a desperate decision. By remaining on the defensive, we could not hope to escape the evil fate hanging over us. It was an act of desperation, but we had to risk everything.”

“Anyway,” Jodl concluded, “there can be no arguments—it is the Führer’s orders!”

The inevitable clash of wills between Hitler and his army commanders took place on December 2 during a six-hour staff meeting in Berlin. In attendance were some 50 officers, including Westphal (representing Rundstedt), Model, Manteuffel, and Dietrich, along with the Führer, Keitel, and Jodl. Model, whose opinion Hitler still valued, urged his chief to reconsider the counterattack’s far-reaching objectives. He then outlined his proposal, Herbstnebel, which would recapture the city of Aachen and thus stabilize matters in the West.

Hitler said no. The generals’ Kleine Lösungwould not accomplish his political goal, he insisted, but instead only prolong the war. “If we succeed,” he continued, “we will have knocked out half the enemy front. Then we’ll see what happens.”

As a sop to Field Marshal Model, the Führer renamed his offensive Autumn Mist, though it still specified the long 125-mile drive on Antwerp. Hitler approved Operation Herbstnebel on December 9, his implementation order bearing the now familiar warning: “Not to be Altered.”

The next day Hitler moved into his Alderhorst (Eagle’s Nest) command post, located near Bad Nauheim in western Germany. Here, during two separate briefings on December 11 and 12, the Führer met with those division commanders who would execute Herbstnebel. The atmosphere was tense, even surreal. Each officer was searched by SS guards before being stripped of his sidearm and briefcase. Inside the conference room more SS sentries stood stone faced behind the generals, who were shocked by their commander in chief’s physical deterioration once Hitler made his entrance.

“He seemed near collapse,” one man later recalled. “His shoulders drooped and his left arm shook as he walked.” But those who remembered the old Hitler saw that master orator return briefly. Eyes blazing, he raged, whispered, and lectured for over two hours. Speaking about the coalition arrayed against him, Germany’s Führer predicted a bloodletting in the Ardennes that would cause the Western Front to “suddenly collapse with a huge clap of thunder.”

Hitler closed his remarks by exhorting the assembled commanders to help him save Germany from its enemies, finally assuring them, “We will yet be masters of our fate.” These officers, many of whom left the conference mesmerized by his performance, then returned to their units to make final preparations. The operation was now set for December 16, and much had to be done beforehand.

Seven panzer divisions, two panzer brigades, and 13 infantry divisions—200,000 men—secretly moved into position opposite the unsuspecting Americans. Matériel stockpiled for Herbstnebel included 970 armored fighting vehicles, 800 aircraft, 1,900 artillery pieces and rocket projectors, 16,000 tons of ammunition, and 4,500,000 gallons of fuel. Fifty thousand horses also were on hand to support the advance.

From his Alderhorst headquarters, Adolf Hitler issued final attack instructions to Field Marshals Rundstedt and Model during the afternoon of December 15. “If you comply with these basic operational guidelines,” he promised, “a great victory is certain.” Then, as was his habit, the Führer busied himself with work far into the night. He finally went to sleep at 5 am on Saturday, December 16, 1944.

Thirty minutes later, a massive artillery barrage opened Hitler’s Ardennes offensive, an offensive that began with optimism and ended in catastrophic failure, hastening the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a writer, historian, and retired military officer from Scotia, New York.