By Kevin H. Hymel

As the Belgian town of La Gleize burned to the ground around him, 29-year-old SS Lt. Col. Joachim Peiper remained calm in his headquarters, listening to reports and issuing orders. Outside, his outnumbered tanks, exchanged fire with American armor.

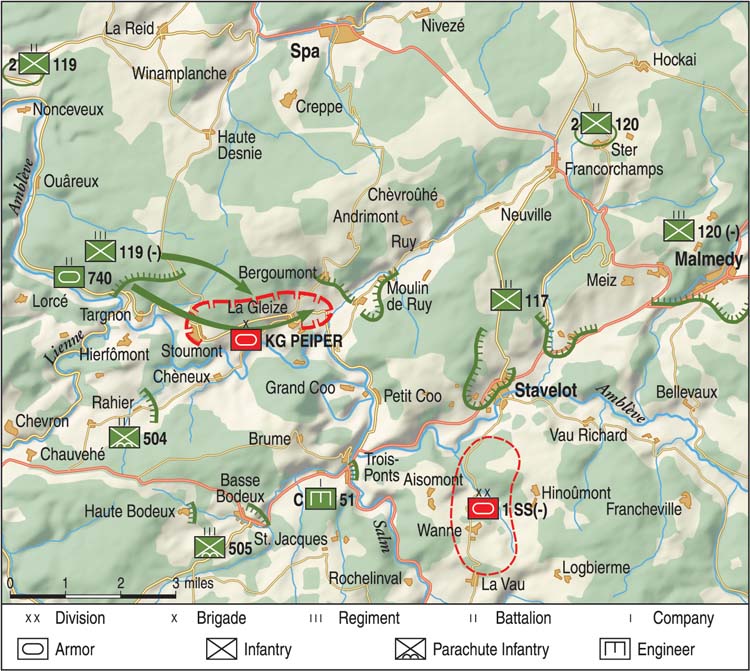

The date was December 22, 1944, and Peiper’s forces clung to the small town, waiting for a relief column to reach them. Peiper had gone into battle six days earlier as the spearhead of Adolf Hitler’s Operation Herbstnebel (Autumn Fog), the Battle of the Bulge. He had started out with 4,800 men, 117 tanks, and numerous other vehicles and heavy weapons. Now he was down to about 800 men and no fuel for his vehicles. How had it come to this?

Cutting a Path to Antwerp

After the Allies’ invasion of Normandy and the subsequent ejection of German forces from France and Belgium in the summer and fall of 1944, Hitler had planned an all-out drive to retake the Belgian port city of Antwerp, an important supply base for the Western Allies, to take place during December, when short days and heavy fog would prevent the Allied air forces from flying.

By cutting a path to Antwerp, his armies would divide the American and British army groups, sending both into a headlong retreat. The two demoralized forces, he believed, could then be pursued and destroyed. Another victory in the West would allow him to refocus his attention in the East, where the Red Army was closing in on the German border.

To capture Antwerp, Hitler created two new armies: General Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army and General Joseph (Sepp) Dietrich’s Sixth SS Panzer Army. They would constitute the main driving force, while General Erich Brandenberger’s Seventh Army would protect the offensive’s southern flank. From north to south along the Belgium-Luxembourg border, the three armies lined up as Dietrich’s Sixth SS Panzer, Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer, and Brandenburg’s Seventh.

Once the breakout had been achieved, so the plan went, Dietrich’s I SS Panzer Corps would drive for the town of Huy near Liège on the Meuse River, some 80 miles behind Allied lines. Once across the Meuse, the II SS Panzer Corps would take over and drive northwest for Antwerp.

convicted of war crimes.

Colonel Wilhelm Mohnke’s 1st SS Panzer Division Liebstandarte SS Adolph Hitler, would spearhead Dietrich’s attack. Serving as Mohnke’s tip of the spear would be a reinforced regiment under Lt. Col. Peiper. The regiment consisted of three tank battalions, supported by artillery and flak battalions, plus engineer and supply companies. Altogether, Peiper commanded 4,800 men and 800 vehicles (117 tanks, 149 half-tracks, 24 artillery pieces, and more than 30 antiaircraft weapons). Mohnke labeled each of his reinforced regiments as battle groups (Kampfgruppen) and named each after their commander, thus creating Kampfgruppen Peiper.

His tankers wore traditional black jackets, while the infantry and antitank units wore gray, both with SS markings on the right lapel and rank on the left. The left sleeve included a Nazi eagle on the arm, distinguishing them as SS, and their division name on their cuff band. Most of the infantry wore camouflaged smocks of orange, green, purple, and brown.

How Joachim Peiper Earned His Command

Joachim Peiper had earned a reputation as an efficient and ruthless warrior on the Eastern Front, for which his men venerated him. “Peiper was the most dynamic man I ever met,” one SS soldier later said. “He just got things done.” Having lived through Allied bombings of Germany, Peiper was also motivated by revenge. After having rescued survivors from an American bombing, he swore to castrate the enemy with a blunt piece of broken glass.

Peiper’s 117 tanks consisted of Mark IV medium tanks, Mark V German Panther heavy tanks, and Tiger II heavy tanks. The Mark IV had served throughout the war and had been upgraded to keep up with enemy technology. Its short-barreled 75mm cannon had been replaced with a long barrel to penetrate thicker armor. Steel plates had been added around its turret and sidetracks, enhancing the tank’s two inches of frontal armor, thus providing better survivability on the battlefield. It was considered equal to the American M4 Sherman tank.

The Panther V likewise fired a 75mm cannon but was classified as a heavy tank with four inches of frontal armor. It was faster and weighed twice as much as the Mark IV. Its sloping armor could better resist all but a point-blank shot from a Sherman.

Finally, the Tiger II, better known as the Royal (or King) Tiger, had no equal on the battlefield. The second generation of the war’s most formidable tank, it dominated the minds of the enemy. To the Allied soldiers, every tank was a Tiger. Its 88mm cannon, in reality an antiaircraft gun, was the most powerful of any tank (until the last months of the war). Its seven inches of frontal armor was the thickest, yet it was slow, prone to mechanical failures, guzzled gas, and weighed too much for many of Europe’s bridges. Peiper considered them more trouble than they were worth in the terrain common in the Low Countries.

“These Roads Were Not for Tanks, but for Bicycles”: Peiper’s Terrain Troubles Begin

Some of Hitler’s planners hoped Peiper might cover the 80 miles to the Meuse River by the end of the first night. Maj. Gen. Fritz Kraemer, Dietrich’s chief of staff, was more pragmatic, projecting a four-day journey. Peiper did not even share Kraemer’s enthusiasm. His route would take him through confined towns on twisting and turning two-lane roads that crossed numerous bridges.

“These roads were not for tanks, but for bicycles,” he explained to his superiors. Unlike the Soviet Union, where open land allowed tanks to spread out for an attack, Peiper’s route condemned his unit to travel in an almost constant column, strung out for miles.

With German fuel stocks dwindling and fuel trucks having difficulty keeping up with the lead tanks, Peiper would need to capture American fuel depots along the way, a dubious prospect at best.

Well before sunrise on December 16, 1944, German artillery exploded on the American lines, signaling the beginning of the offensive. During the night, Peiper had moved his unit into a wood north of the town of Stadtkyll and waited for the 3rd Parachute Division to crack the American line. He waited most of the day, until he received word at 4:00 pm to advance. The tanks and half-tracks rolled west, reaching a blown-out railway bridge in less than an hour. Undeterred, Peiper ordered his tankers to drive into the depression and out the other end.

As his panzers advanced, one tank plowed into a minefield, detonating a mine. Another followed. Engineers had to clear minefields as the sun set. The loss of the tanks led Lieutenant Werner Sternebeck to lament, “Our two Panthers, which were thought of as battering rams, were lost for the rest of the deployment without having made any contact with the enemy.” Not long after that, Sternebeck’s tank hit a mine.

15 Miles into Peiper’s Advance: A Long Day for German Forces

Around midnight, Peiper’s tanks rolled into Lanzerath—several hours behind schedule—where an American platoon had held up an entire parachute regiment most of the day. A furious Peiper stormed into the regimental headquarters in the Café Stolzen and demanded to know who was in charge. When Colonel I.G. Hoffmann identified himself, Peiper asked, “Why have you stopped?” Hoffman outranked Peiper, but he knew better than to correct an SS officer. Hoffman explained that the enemy was too strong and the battlefield mined. When Hoffman tried to explain the situation on a map, Peiper picked it up and, using two bayonets, pinned it to the wall near a lantern.

Peiper then called a major on the telephone. When the major admitted he had not reconnoitered the area, Peiper got a captain on the phone who reported the same. Infuriated, he slammed down the phone and shouted, “There’s nothing out there!” Then he demanded that one of Hoffman’s parachute battalions join his attack on Honsfeld, which he had scheduled for 4 am the next morning, promising to plow through any American mines.

Peiper spent the rest of the night reorganizing his unit for the attack. Half-tracks would lead the way, followed by tanks with some paratroopers riding atop while others cleared the woods on either side of the roads. Peiper, whom his commanders had hoped might sprint the 80 miles to the Meuse on the first day, had traveled only 15 miles and was 18 hours behind schedule.

Before dawn the next morning, Peiper’s men headed north in a sleeting rain. To prevent drivers from using their lights in the darkness, paratroopers guided them by waving white handkerchiefs. The column bypassed a few homes occupied by sleeping American soldiers. Within a half hour, the Germans reached Honsfeld, waking up the occupying Americans.

The spearhead half-tracks continued through the town, while the followup troops shot at the houses’ windows. Some 15 Americans returned fire, picking off Germans in the street, but the outnumbered Americans soon surrendered. The SS troops rounded up their prisoners, with their hands above their heads, and gunned them down with machine pistols. Other surrendering Americans were sent to the rear.

The Tank Column Makes Contact with American Allies

The Germans sacked Honsfeld’s church and homes, stealing food, valuables, and clothes. Paratroopers stripped the boots off dead Americans lying in the street and laced them on. They then found civilians huddled in the church basement and had them clear debris from the streets. (A few days later, after the spearhead tanks had long gone and followup troops marched west, five SS soldiers entered a home and shouted downstairs that they needed a guide. One of the adults volunteered, but the Germans picked the pretty, 16-year-old Erna Colla. Her family would never see her again.)

Joachim Peiper’s spearhead continued north to Büllingen. Along the way, the men encountered an American truck column heading south. An SS soldier in the lead scout car flashed a red flashlight, and the trucks stopped. Again, the Americans surrendered, only to be cut down. “They were unarmed and held their hands in surrender position,” explained one of Peiper’s men, Siegfried Jaekel. “I shot at them with my pistol for two or three rounds.”

As the half-tracks approached Büllingen, they captured a company of Americans lining up for breakfast. American engineers then opened fire on the Germans with rifles, machine guns, and grenades. They also fired flares into the air, signaling their battalion that the Germans were coming.

Some of Peiper’s tanks left the column to blast aircraft lining an airfield. As Peiper urged his men on, they pushed the Americans through the town, although the GIs, firing from the surrounding buildings into open half-tracks, killed and wounded a number of Germans, including two platoon leaders. One engineer blasted a Mark IV panzer with a bazooka while his comrades cut down the crew bolting from the burning machine.

In the confusing fight, the Germans became disoriented and headed north, not west, out of the town. Farther up the road, an American antitank gun hit a lead Panther tank in the turret and killed its commander. The SS column backed down to Büllingen where an old man wearing a Nazi armband stepped out of his house and showed the Germans where the Americans’ supply dumps were. The SS tankers put some 200 captured Americans to work refueling their tanks with American gas before sending them to the rear.

The Real Story Behind the Malmedy Massacre

Refueled, the column quickly headed west, passing unhindered through the villages of Domane, Shoppen, Odenvaal, and Thirimont. When the vehicles and tanks reached a crossroads at Baugnez, they ran into another column of American trucks, this time from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. Panther tanks opened fire. Trucks veered into drainage ditches along the road, others simply hit the brakes. The Germans quickly gathered the men, again, with their hands above their heads, and led them to a field north of the intersection.

As Peiper rolled by in a half-track, he called out to the surrendering Americans: “It’s a long way to Tipperary, boys,” the title of a popular British World War I song. He then asked an American if he could drive and, receiving a negative response, removed the man’s ammunition bandolier, telling him, “You won’t be needing this anymore.”

Several of the SS dismounted to pilfer food from the trucks or round up prisoners. Peiper spotted them and shouted, “Goddamit! What kind of business is it to stop here for hours?” Then he scornfully told a tank commander, “The little that has to be done here, the men in the rear will do!” and pushed on.

About 130 Americans stood in the field, wondering their fate. When an SS engineer asked Major Werner Pötschke, the battalion commander, what to do with the prisoners, he told him, “Shoot them.”

Lieutenant Lloyd Iams, an American who spoke German, overheard the conversation and told Staff Sergeant Henry Zach, “They’re going to kill us.” Before they could react, SS Lieutenant Erich Rumpf shot into the prisoners with a P-38 revolver and was immediately joined by men in their half-tracks and tanks. Fire swept the field. The Americans collapsed, some screaming or moaning in pain, others praying out loud.

After a few minutes of fire, SS men walked among the bleeding Americans, kicking them to check for signs of life. “Hey Joe!” they would call out. Anyone who reacted was subsequently shot in the head.

“A single American was standing up straight,” recalled Panther tanker Georg Fleps. “I pointed my pistol at him and fired. Watching my shots, I saw him fall.” The soldier was probably Sergeant Don Geisler who stood up after the initial fire. After collapsing, he staggered to his feet a third time until machine-gun fire finally killed him.

The Germans kicked Lieutenant Iams, and he stood up, only to be shot in the head, falling backward onto the ground. “I’ll give that lieutenant credit,” Zach later said. “He never begged or whimpered or anything.” Another American, Kenny Kingston, pleaded in vain to a German, “Please don’t shoot me!” before he received a fatal bullet. Amazingly, Kingston survived the ordeal.

The Germans then removed from the dead their rings and watches. One German tanker, Hubert Huber, kicked and shot Americans until he came to a wounded man and ordered him to take off his overshoes. Once the American complied, Huber shot him in the head. The massacre took less than 15 minutes.

The Germans mounted up and continued west. Back on the field, passing tanks continued to shoot the Americans. Some had survived by either holding their breath so the Germans wouldn’t see mist exiting their mouths or staying quiet while the Germans kicked them. Private James Mattera, who had escaped injury, called out, “Let’s go!” and got to his feet. Others followed and staggered away, some carrying others. The Germans rolling by fired at the fleeing Americans and even set a small café afire where some of the Americans were hidden, burning to death the Americans and the woman who owned the café.

Altogether, 84 Americans died at Baugnez while 57 survived. A handful made it north to the town of Malmedy, where they reported what had happened. The incident became widely known in the U.S. Army as the Malmedy Massacre, and word of it spread like wildfire. Any captured SS troops stood little chance reaching an Allied prisoner-of-war camp. (You can read more about the Bulge and the events that shaped the fighting in the European Theater inside WWII History magazine.)

36 Miles into Peiper’s Advance: “The Gas Pedal Is Stuck. We’re Hit!”

Peiper’s men next entered Ligneuville, where they hoped to capture an American brigade commander, but he had slipped out. Americans, however, were still in the area. A Mark IV headed toward a bridge, only to be blasted from behind by an American Sherman tank. American riflemen then opened fire from nearby houses as the tankers escaped their burning vehicle. Another tank round destroyed a German half-track.

Peiper jumped from his own half-track with a Panzerfaust antitank weapon, ran into a house, and was preparing to fire when an artillery-mounted half-track knocked out the Sherman. The Germans soon crossed the bridge and headed to Stavelot.

As the sun set, Peiper’s column snaked along a narrow road, with a steep hill to the right and a deep slope to the left. As the lead tank crept around a tight corner, someone shouted out, “Halt!” The tanks opened up. The lone American who challenged them fired back with his rifle.

The few Americans defending the curve—a company of engineers—had placed mines along the road and had prepared the bridge ahead for demolition. Peiper, thinking he was up against a strong enemy, decided to rest for the night and attack Stavelot in the morning (he would later claim he was up against American armor that attacked him, but only a handful of engineers stood in his way). He had traveled 36 miles. He was not even halfway to the Meuse.

Before dawn the next morning, December 18, Peiper’s tanks started forward. American tanks and tank destroyers had rushed to the town overnight to challenge him. As the sky turned from black to gray, an American antitank gun protecting a narrow stone bridge over the Ambleve River hit the lead Panther tank. “The gas pedal is stuck. We’re hit!” shouted the driver to the tank commander, who ordered the gunner to take out the American gun. “Open fire!” The first round missed, but the second shattered the antitank gun, showering pieces onto the German tank. It then rolled across the bridge.

While the lead tank slugged it out on the bridge, two American M-10 tank destroyers blasted the tanks lined up behind it. “The Americans blanketed us with fire from a variety of calibers,” recalled one SS man. Slowly, the German tankers pushed the Americans back into the town. Just the sight of King Tiger tanks demoralized the Americans, who knew they possessed nothing to stop the behemoths. “It had cost us several panzers and wounded,” reported one German, “but the bridge over the Ambleve was open.”

How the Americans Blow up the Ambleve Bridge Before Peiper’s Unit Could Cross

Even though the Americans continued to fight in Stavelot, Peiper’s tankers burst west, headed to Trois Ponts, a town where three bridges crossed the connecting Salm and Ambleve Rivers (hence the town’s name). To reach it, Peiper sent his main force west to cross the Ambleve and a smaller force of Mark IV tanks south to cross the Salm.

As the main force approached two railway underpasses outside Trois Ponts, an American antitank gun fired at the lead panzer, grazing it. The German commander fired back, aiming his cannon by looking down its barrel. “One high-explosive shell, and there was no more resistance,” he reported. He did not see the wounded American engineer retreating into the town.

The engineer warned his fellow engineers about the approaching column, and they promptly blew the Ambleve bridge before pulling back. The Germans, furious about being denied their bridge, fired on several civilians. One SS soldier chased down a teenage boy and executed him.

Denied the fast route west, Peiper’s men had no choice but to turn north, but that road was blocked by a stack of mines. The lead tank fired a round at the mines. “The pile of mines blew into the air with an extraordinary explosion,” said the commander. “We continued the advance.”

The American engineers at the Salm River bridge probably heard the action but remained at their bridge. When Peiper’s southern force approached, the engineers fired on the tanks with bazookas, but they bounced off the Mark IVs’ hulls.

The engineers pulled back behind the bridge. As the tanks roared up to the bridge, the engineers blew it up. The column, low on fuel and blocked by the downed bridge, would go no farther. “Back to the starting point and follow the lead,” Peiper radioed the unit commander. The men had to transfer the fuel from half their tanks to drive the others back.

The main column headed north toward La Glieze, then turned southwest toward Cheneux. As the column raced west, the skies cleared, and a flight of 16 P-47 American Thunderbolt fighter aircraft dove on the column. Men hurried into and under their tanks while the antiaircraft gunners returned fire. Aircraft strafed and bombed the column.

“The men on the two guns ignored the sweat on their faces and anxiety in their throats as they were continuously attacked by the aircraft,” recalled one of the flak gunners. The fighter planes knocked out three Panthers and five half-tracks, along with accounting for a number of dead and wounded, while the gunners managed to down only one Thunderbolt. The attack lasted more than an hour.

Peiper Loses His Path to the Meuse River to American Combat Engineers

As the fighter planes flew away, the column took off again, the men hoping to cross the Lienne River and reach Werbomont. As the tanks approached the bridge in the gathering darkness, around 4:45 pm, the lead Tiger II gunner spotted American engineers ahead and fired a round from his 88mm cannon. The Americans scattered, leaving their detonator behind.

One engineer, realizing the mishap, ran back and grabbed it. At his officer’s signal, he set off 2,500 pounds of TNT packed under the bridge. An explosion boomed across the hills. Bits of concrete and steel flew in every direction. The bridge was gone.

“Those damn engineers!” Peiper shouted. “Those damn engineers!” As he cursed, more Tiger IIs spread out and brought the Americans under fire. A firefight ensued, and Peiper lost two half-tracks and a number of men, but it meant nothing. He had lost the most direct path to the Meuse River. He was 26 miles short of his goal.

Not all was lost. Peiper had sent a company of six half-tracks north to reconnoiter another bridge to see if it could hold tanks. The half-tracks roared across the narrow bridge (which was barely wide enough to handle them) and turned south, paralleling the river’s west bank. Suddenly, one of the half-tracks hit a mine and flipped completely over.

As the hour approached midnight, the other half-tracks raced south, firing into houses, to link up with Peiper. As they approached the left turn that would put them at Peiper’s bridge, the lead half-track driver flicked his light to spot the turn. Two American tank destroyers, hidden in the dark, saw the light and immediately opened fire. One blasted three rounds into the lead half-track. The resulting explosion lit up the whole area.

American infantry fired at the column from homes and trenches. One of the half-tracks tried to turn around but succumbed to American fire; the Germans abandoned the third. The last two managed to turn around, but as they fled, American Pfc. Mason Armstrong fired bazooka rounds at them from a second-story window, knocking both out.

The surviving Germans worked their way back from where they had come, and their commander reported to Peiper that the northern bridge could not support tanks. With nowhere else to go, Peiper turned back toward La Gleize. Not all his tanks made it. One stalled from mechanical problems.

50 Miles into Peiper’s Advance: Slowed Down in Stoumont

Meanwhile, problems were growing to the east. The Americans counterattacked at Stavelot, capturing the northern half of the city and keeping relief forces from reaching Peiper. In addition, American Maj. Gen. James Gavin and elements of his 82nd Airborne Division had reached the bridge where the half-tracks had crossed. American forces were building to eject Peiper from Belgium.

Since advancing southwest had failed, Peiper would now head northwest toward Liège through the town of Stoumont, which was only two miles away. The tanks started off in a heavy fog around 7 am, overrunning antitank guns set up on the eastern edge of Stoumont. Other antitank guns in the town and tanks hidden in the woods opened fire at point-blank range. The Germans ground to a halt amid the heavy fire. Major Werner Poetchke urged his tankers forward, but the fire was too intense.

The Americans managed to jam a Panther tank’s turret. “I was trying to aim our gun at the antitank gun, despite the jamming,” explained the tank’s gunner. “We were hit in the engine compartment by an antitank gun shell from the left.” As the tank began to burn, the crew bailed out.

German tanks began to back up until Poetchke jumped out of his tank, armed with a Panzerfaust, and threatened to kill any man who retreated. The tanks pushed forward as rounds ricocheted off their sloping armor. Somehow, they missed the landmines the Americans had laid out.

After a two-hour battle, the Americans pulled back through Stoumont. The Germans rounded up prisoners, dragging Americans from their hiding places. When a civilian teacher, worried about the fate of the Americans, asked a German officer for a doctor to treat a wounded American, the German snapped, “All the people around here are terrorists!” Peiper later entered the town, and as he checked the condition of the American antitank guns, an artillery barrage crashed around him. He jumped into the back of a house. When it was safe, he proceeded in a jeep through the rest of the town.

The Americans retreated west through the town of Targnon and the Stoumont railway station. As they pulled back, the crew of an antiaircraft gun, acting as a rear guard, leveled their barrel and blasted a pursuing half-track and Panther tank. The Germans returned fire, knocking out the gun. German infantry and paratroopers quickly dismounted and captured the station.

Then the Americans counterattacked. Out of the late afternoon fog, Sherman tanks rolled east. At a curve in the road, the lead Sherman fired on a Panther only 200 yards away. The round hit just below the gun base and ricocheted down into the tank. It started to burn. The American tank advanced and fired another round, this time at the followup tank. The closely fired round penetrated the Panther’s sloping armor, stopping it.

When the American tanker fired at the third Panther, his gun jammed. The Panther fired several rounds but failed to knock out the Sherman. Instead, an M-36 tank destroyer, immediately behind the Sherman, fired off a 90mm round that penetrated the Panther’s turret. Subsequent rounds set the German tank ablaze.

The knocked-out tanks blocked the road, stopping Peiper’s reinforced regiment in its tracks. The spearhead of Hitler’s attack west had come to a violent end. Peiper had traversed 50 miles of the 80 he needed to reach the Meuse.

Peiper Holds in La Gleize…

Peiper now focused on keeping his tanks and men in La Gleize alive and sustained. His tanks were just about out of fuel, and his men had barely eaten or slept in days. They were, much like his offensive, exhausted. He attacked again, this time eastward, hoping to reach Stavelot for resupply, but American outposts between Stavelot and La Gleize stopped his men cold.

Stavelot was no safe haven, either. The Americans continued to fight for the town, pummeling Germans on the southern bank of the Ambleve with tanks and artillery. One German officer described the scene: “A knocked out Panther, numerous burning vehicles, a heavy 9.2cm American antitank gun, noise, smoke, and dead comrades.”

The Americans fought savagely after they discovered more than 130 civilians, half of whom were women and children, sprawled dead in the streets. Officers had to restrain their men from killing surrendering SS soldiers.

The Germans repeatedly tried to capture the city’s main bridge, only to be repulsed. “We were immediately barraged with heavy antitank and mortar fire, and infantry fire as well,” one German soldier reported. Later that day, the Americans blew up the bridge, preventing the Germans from pushing north.

Peiper spent the next four days holding out in La Gleize. On December 20, the Americans recaptured Targnon, east of Stoumont Station, but failed to retake Stoumont. Peiper’s men repeatedly counterattacked but only managed to push the Americans back about 100 yards. Some of the heaviest fighting occurred for two days around a sanatorium west of the town. Amazingly, none of the 260 locals who had taken refuge in the sanatorium’s basement were killed.

The next day, Peiper learned that German forces in Stavelot were trying to push west to relieve him. Deciding to hold on until relieved, he pulled his tanks out of Stoumont. He would make La Gleize a fortress until his comrades reached him.

…Which Became a “Burning Tomb”

By December 22, the Americans closed in on Peiper from the north, east, and west. The Germans referred to La Gleize as Der Kessel (the cauldron). American numeric superiority in tanks and artillery suppressed Peiper’s heavy tanks. Phosphorus rounds crashed into the town’s church steeple and set the structure on fire. One Tiger II absorbed so many Sherman tank rounds the entire crew became concussed. One shot from another Sherman knocked the cannon off a Tiger II, rendering it useless. It would never leave La Gleize. (Its battered hull remains outside a museum in the town.) Most of the other tanks ran out of fuel while repulsing the attacks.

Through it all, Peiper remained calm, issuing orders and questioning his commanders as they reported to him. When he learned of the death of a friend, his lips pursed and fists tightened, but then he returned to the business at hand. “That was Peiper,” one of his men explained, “the man who gave even the last of his men so much support and a strong sense of security.”

That night, German Ju-52 transport planes flew over and dropped supplies. Unfortunately, they ended up in American lines or in no-man’s-land. To make matters worse, Peiper later learned there would be no rescue attempt for his survivors.

In the late afternoon of the next day, as the Americans tightened their vise on La Gleize, Colonel Mohnke finally gave Peiper permission to break out; American prisoners and his own wounded would be left behind. His vehicles—heavy and medium tanks and half-tracks—long out of fuel, would be torched. The men would escape on foot in the only direction still open: southeast.

A few hours into December 24, Germans quietly spoke the password to one another: “Merry Christmas.” They dropped grenades into their vehicles or set timed charges in the tanks. Peiper ordered that the charges be staggered to give the impression of firing. The Germans plucked two farmers to act as guides. Then, some 800 men silently headed south over frozen roads and into the woods. “Our knees trembled to the point of near collapse,” recalled one German, “but we had to hold on.” He eventually turned around to look at La Gleize. “We saw only a burning tomb.”

All for Naught: Peiper Never Makes it to the Meuse

Peiper worked his way back and forth along the column offering encouragement to his men. By 5 am, the men could hear the charges going off. “Inside 30 minutes the entire area formerly occupied by Colonel Peiper’s command was a sea of fiercely burning vehicles,” reported American Major Hal McGown, a POW with Peiper’s retreat.

For the entire day, they climbed hills and forded streams. As evening approached, they clashed with an American patrol near Trois Ponts but managed to disengage after 20 minutes of fighting. Somewhere along the way, enemy fire had ripped into Peiper’s right hand.

Early the next morning, Christmas Day, the men reached the Salm River, but Americans were on guard at all the bridges. The men found a spot shallow enough to cross the 38-yard-wide river. The stronger men rolled rocks into the river for steppingstones and the men formed a chain to get everyone across. In some spots, the men stood in chest-deep freezing water. “As we emerged, all our belongings had frozen stiff,” remembered one man.

They then climbed a hill to the town of Wanne, inside German lines. To the men of the 1st SS Panzer Division, Peiper and his men looked like “walking icicles.” They were dirty, unshaven, exhausted, and totally whipped. Peiper reported to an aid station. As a doctor treated his right hand, he told him, “We left with 3,000 men from Germany and now we have 717.”

He then waved his hand in the direction from which he had come. “You can find the others the whole way along our path.” His numbers were a bit off, but he made his point. His troops had taken a beating. A final roll call revealed that 770 men of the 800 men who left La Gleize survived.

Peiper had failed in his mission to reach the Meuse River. He had gone into battle 10 days earlier with 4,800 men, 117 tanks, and numerous other vehicles and heavy weapons. He came out with a fraction of troops and none of his tanks or vehicles. While he had caused near panic in the American chain of command, the men on the ground—engineers, soldiers, tankers, and artillerymen—as well as American fighter aircraft had slowed and then stopped his force cold.

Peiper’s men had penetrated farther than any other German unit, but it was all for naught. The Meuse River was never crossed, and Antwerp never came under threat. In stopping Peiper, the Americans had won a decisive battle.

While Peiper’s destruction can be measured by the casualties on both sides and the number of tanks and vehicles destroyed, there is no metric to measure the pain and misery inflicted, only anecdotal evidence. Thus is the destruction of war.

In May 1945, long after the campaign, the winter snows melted to reveal 16-year-old Erna Collas’s body, the girl from Honsfeld the Germans had picked as a guide. She was discovered in a foxhole near the road to Büllingen with seven bullet holes in her back. The science of the time could not reveal what else Joachim Peiper’s men had done to her.