By Joshua Shepherd

During the early morning hours of May 27, 1942, the men of the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade braced themselves for another mundane assignment in the broiling heat of the Libyan Desert. Positioned to the south of the Gazala Line, the British Eighth Army’s defensive stronghold, the Indians were tasked with providing a measure of flank security against a potential Axis attack. Although German forces were known to be on the move farther to the north, the Indians had enjoyed a quiet night in their sector.

Bedlam erupted shortly after 6 am. To the west, the telltale dust cloud of an enemy column blurred the horizon, and as the troops squinted for a better look, they were greeted with an unwelcome sight. Storming out of the dust were scores of panzers deployed in assault formations. They were heading straight for the Indian position. The superior numbers of panzers overwhelmed the men of the Motor Brigade within a matter of minutes.

The Motor Brigade’s headquarters sent out a desperate plea for reinforcements. The plea noted the arrival of an entire division of enemy panzers. The hapless troops of the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade faced the spearhead of Generaloberst Erwin Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika, which was opening what was destined to be one of the most storied armored clashes of World War II.

Ironically, Germany initially had no interest in the contest for North Africa. Following the stunning German victories in France during the spring of 1940, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini abruptly joined the global conflict, declaring war on both France and England. The bellicose Mussolini not only hoped to grasp the strategic coattails of his German allies, but also to expand Italy’s holdings in North Africa.

On September 13, 1940, Mussolini unleashed an 80,000-man invasion force. After regrouping, the British counterattacked in December. The entire affair degenerated into an embarrassing fiasco for Mussolini. The British brushed aside ill-trained and poorly equipped Italian troops. After dispersing the Italians, the British pierced the Libyan border and drove deep into the province of Cyrenaica. By the close of January 1941, the British had plunged more than 300 miles into Libya. In the process, they overran the Italian Army, capturing 130,000 prisoners, 1,000 pieces of artillery, and 400 tanks. Most important, the British had seized the strategic port of Tobruk.

With Libya on the verge of collapse, German Führer Adolf Hitler, although annoyed by what he considered Italian incompetence, felt obliged to intervene on behalf of his Axis partner. Although he continued to regard North Africa as a sideshow to the conflict on the European mainland, Hitler nonetheless was eager to maintain pressure on the British Empire. On February 9, Hitler informed Mussolini that help was on the way. The German leader had decided to reinforce the flagging Italian Army with two German divisions.

Although two divisions may not have seemed like sufficient reinforcements for the task at hand, the two divisions were composed of veteran armored troops. The Italians would be reinforced with the 5th Light Division, a mechanized outfit that included armored elements, followed by the hard-hitting panzers of the 15th Panzer Division.

Although he would eventually attain near mythic status in military history, in 1941 Rommel was merely a successful divisional commander whose capacity for higher leadership was as yet unproven. But in an army whose officer corps was traditionally dominated by the Prussian aristocracy, Rommel had risen to the highest echelon through a remarkable combination of personal bravery, outright hard work, and an innate strategic horse sense.

Briefed on developments in North Africa by Wehrmacht Commander in Chief Field Marshall Walter von Brauchitsch, Rommel was given command of the newly christened Afrika Korps. Von Brauchitsch made it clear that Rommel’s assignment was purely defensive in nature and largely confined to simply bolstering the Italian defenses. The indefatigable Rommel arrived in Tripoli on February 12, 1941, and immediately set out for a personal reconnaissance of the front.

He found the existing tactical dispositions alarming and the British poised for a renewed strike farther into Libya. As an officer who had seen a good bit of fighting against the Italians during World War I, Rommel had little faith in the reliability of his Italian allies. Although he ostensibly served under Italian command, he held little regard for their fighting abilities. The Italians “were no good at war,” he tersely observed.

Rather than passively await a renewed British offensive, Rommel quickly decided to establish defensive positions closer to the enemy, planting a forward operating base at Sirte, 250 miles east of Tripoli. Despite protests from hesitant Italian commanders, within a week Rommel had occupied Sirte with three Italian divisions and two battalions of newly arrived German troops. With little regard for the ungainly Axis chain of command, Rommel began shaping the war in North Africa according to his own strategic vision.

But the British were in no condition to renew an attack. In March 1941 Great Britain had launched a counterattack against Axis forces in Greece. The British had stripped the Western Desert Force of much of its fighting strength for the counterattack. By the time Rommel arrived in the theater, the British Army in Libya was reduced to a skeletal force. Worse yet, field command had devolved to Lt. Gen. Philip Neame, an engineering officer with little combat experience.

Sensing an opportunity, Rommel returned to Berlin on March 19 to plead for authorization to attack the weakened British forces. An inherently aggressive field commander, Rommel was determined to seize the initiative while the odds were favorable. Field Marshall von Brauchitsch, who had no desire to widen the conflict in North Africa, flatly denied the proposal, ordering Rommel to maintain a defensive posture.

As soon as he returned to Libya, Rommel began waging war on his own terms. On the pretext of defending one of his outposts, he threw forward the 5th Panzer Regiment on March 24. Despite Italian insistence that he halt the advance, Rommel ignored the orders and by the first week of April, the Germans had seized the port of Benghazi, captured Lt. Gen. Neame, and were driving toward the Egyptian frontier.

The British were outmatched but far from panicked. General Archibald Wavell, overall commander in Egypt, ordered a stern defense of the strategic port at Tobruk in northeastern Cyrenaica. Although the town was rapidly bypassed by Rommel’s columns, its continued occupation by British troops would gravely threaten Axis lines of communication. Alarmed at the danger to his supply lines, Rommel ordered an assault on the city.

On April 14, he attacked with the 5th Light Division, which was badly chewed up by the 9th Australian Division. Two days later a desperate Rommel tried again, attacking with two Italian divisions that fared no better. The stubborn British garrison at Tobruk endured a protracted trial of siege and bombardment, but it refused to capitulate. After drawing up the bulk of his reserves, Rommel assaulted the city once again on April 30 but was handily repulsed. Bloodied by the stubborn garrison of Tobruk, Rommel was at last halted by Berlin. Alarmed that Axis forces in Cyrenaica were dangerously overextended, von Brauchitsch flatly ordered Rommel to call off any further advance and consolidate his gains.

Far from surrendering the strategic initiative, Wavell regrouped his forces and launched an initial counterattack on May 15. Although the British initially made good progress, Rommel eventually pushed them back to the Egyptian border and succeeded in securing the strategic Halfaya Pass. One month later, Wavell launched a major offensive into Cyrenaica. Codenamed Operation Battleaxe, the entire assault went poorly for the British. A stiff German defense denied the British possession of Halfaya Pass, and Rommel succeeded in once again throwing Wavell’s forces back in confusion. Repeated success brought further honors. Rommel was promoted to the rank of General der Panzertruppe in June. As for the Afrika Korps, which received reinforcements, it was elevated to Panzergruppe Afrika.

For his part, Churchill had had enough of the strategic quagmire in North Africa and abruptly ordered Wavell reassigned to India. His replacement, who assumed the job with heavy expectations, was General Claude Auchinleck. Auchinleck was a highly respected career officer. A graduate of the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, the professionally trained Auchinleck had spent the bulk of his career on the Indian subcontinent, ultimately serving as commander in chief in India. After Wavell’s ouster, Auchinleck became commander in chief of British forces in the Middle East and proved popular with his subordinates. He seemed to be the ideal supreme commander for the difficult Allied campaign in North Africa. He was highly intelligent, even tempered, and cool under pressure.

Auchinleck tackled the daunting task of relieving Tobruk and driving Axis forces back into Libya. The British high command heavily reinforced the Western Desert Force. Reinforced to nearly three times its original strength, it was redesignated as the Eighth Army. Auchinleck in turn appointed Lt. Gen. Sir Alan Cunningham to carry the fight to Rommel. For the work at hand, Cunningham had 700 tanks, 600 artillery pieces, and 118,000 Commonwealth soldiers determined to restore British honor.

Appropriately codenamed Operation Crusader, Cunningham launched the grand operation on November 18, 1941. Striking for the wayside village of Gabr Saleh, Cunningham had armored elements of his XXX Corps skirt the Axis flank and secure one of the enemy’s major supply routes. The two sides sparred and jockeyed for position for four days. Believing he was facing little more than a minor British raid, Rommel struck back on November 23.

The 21st Panzer Division slammed into the complacent tankers of the British 7th Armored Brigade at Sidi Rezegh. Both sides funneled reinforcements into the fight, but Rommel gained the upper hand by consolidating his forces. In two days of fierce fighting, British columns, thrown piecemeal into the battle, suffered heavy casualties.

Cunningham was rattled by the losses. Apprehensive that the entire operation was a disaster, he brought Auchinleck to the front for a personal consultation and then suggested a retreat. The iron-nerved Auchinleck, who was convinced that Rommel’s lines of communication were stretched to the breaking point, ordered Operation Crusader to proceed.

The gamble paid off. Rommel’s forces were indeed left battered after the fighting, and the New Zealand Division succeeded in breaking through to the besieged garrison of Tobruk. In the midst of the success, Auchinleck removed Cunningham from field command in large part because the general had been exhibiting signs of increasing stress. To head the Eighth Army, Auchinleck selected 44-year-old Maj. Gen. Neil Ritchie, the British Army’s youngest general; however, Auchinleck began wielding more direct power at the front, and thus became the de facto British field commander in North Africa.

Despite the potentially uncomfortable chain of command, Auchinleck and Ritchie achieved stunning success. In a whirlwind campaign that December, the Eighth Army executed a skillful flanking maneuver that pried Rommel’s troops away from defensive positions in the vicinity of Gazala. British troops mounted an unrelenting pursuit over the succeeding month, and Axis forces were driven out of Cyrenaica. To his credit, Rommel had succeeded in executing a skillful withdrawal and rallied his forces at El Agheila.

Despite the embarrassing defeat, the indefatigable Rommel had reason for optimism. Due to the global nature of the war, the delicate balance of power in North Africa had suddenly tilted in favor of the Axis. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japan launched a wide-ranging offensive that threatened British possessions in the Far East. Reinforcements that had been slated for the Eighth Army were abruptly transferred instead to Southeast Asia.

Rommel found himself at the command of a well-supplied veteran fighting force with an expanded command structure. His forces were redesignated Panzer Armee Afrika in January 1942.

Panzer Armee Afrika had two main components: the Afrika Korps and the Italian XX Corps. Rommel directed these forces himself. The Afrika Korps was a fearsome war machine composed of hardened veterans. Consisting of the 15th Panzer Division, the 21st Panzer Division, and the 90th Light Division, the corps contained a potent mix of armor, artillery, and mechanized infantry, all trained to operate in the combined arms approach favored by German military doctrine. The Italian XX Motorized Corps was composed of the armored 132nd Division Ariete and the 101st Division Trieste, a mechanized infantry unit.

The other component was Infantry Gruppe Cruwell, which was commanded by General der Panzertruppe Ludwig Cruwell. It consisted of the Italian X and XXI Corps with a combined total of three infantry divisions and one motorized division.

The Afrika Korps was a seasoned force equipped with some of the best armor Germany produced. With such a tool at his disposal, Rommel had no intention of sitting idle. On January 21, 1942, Rommel was on the move for the forward British operating base at El Agheila. Unprepared British defenders fled in short order and once again abandoned Cyrenaica to the enemy. Speeding through eastern Libya, the Germans pushed on to Benghazi, seizing a healthy stockpile of supplies.

British forces continued to fall back in confusion, and much of the blame was laid at Ritchie’s feet. Increasingly considered paranoid and overly sensitive by a number of subordinates, the general was widely thought to be in over his head. Auchinleck came to agree with the assessment, but realized that the continued sacking of Eighth Army commanders would be devastating to morale. Ritchie remained in command.

Having escaped Rommel’s steamroller, the British succeeded in feverishly constructing a strong defensive position that extended south from the coastal village of Gazala. The line controlled access to eastern Cyrenaica and shielded the vital port at Tobruk. The defenses ran south from Gazala for 40 miles to Bir Hacheim. To protect the British left flank, the line angled sharply another 20 miles to the northeast. The position was shielded by wide belts of mine fields, but the defenses centered on a half-dozen fixed positions known as boxes. Roughly a mile square, the boxes were laced with barbed wire, bunkers, and pillboxes and were designed to break up enemy tank columns until British armor could arrive to finish the job.

Confronted with such a formidable obstacle, Rommel consolidated his gains and waited for a better opportunity. Yet his British opponents were far from lulled into complacency. Rommel’s native genius for desert warfare was quickly earning him a fearsome reputation and his legendary nom de guerre, Desert Fox. Lionized in the German press and feared by his British opponents, his presence on the battlefield exuded an aura of assured victory.

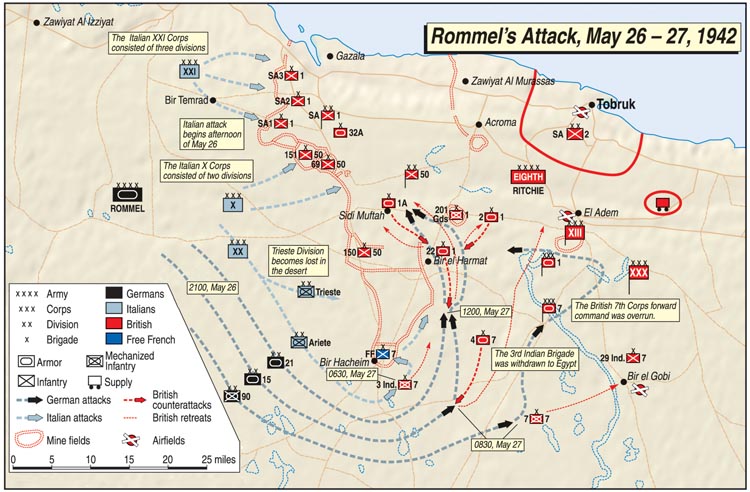

Rommel would soon prove that the British had just cause for entertaining such sentiments. On May 26, 1942, Panzerarmee Afrika was on the move, stirring up immense clouds of dust and drawing the attention of British observers. German artillery likewise opened up while flights of Stuka dive bombers pounded British positions. At the outset, it appeared that Axis forces had targeted the northern half of the Gazala line, centering much of their attention on the vital crossroads of the desert routes known as the Trig Capuzzo and Trig el Abd. As dusk fell, British troops braced for an all-out attack the following morning.

But Rommel had other plans. The perceived attack on the northern reaches of the Gazala Line was little more than a cleverly executed feint. Armored units began pulling out of line after dark. They sped south to link up with the primary armored strike force, the Afrika Korps, which Rommel intended to personally lead in a wide sweep around the British left flank.

While Rommel led the Afrika Korps in a dash for the British rear, the Italian Ariete Division was assigned the task of assaulting Bir Hacheim, the linchpin of Allied defenses. When the Italian armor rolled toward its objective, it unexpectedly blundered into the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade. Outnumbered and taken entirely by surprise, a fierce Italian assault wrecked the brigade. In just 30 minutes the Italians had cleared their front and were once again driving for Bir Hacheim.

The Italians ran into a harder fight in short order. Approaching Bir Hacheim, they were taken under a murderous fire from Allied troops manning a stout defensive box surrounded by minefields. The position was manned by a Free French brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. Pierre Koenig, a tough career officer who possessed a remarkable rapport with his men. Koenig, affectionately known as “Old Rabbit” to his devoted soldiers, succeeded in driving off the Italian assault. But aware of the value of Bir Hacheim to British defenses, he realized that further attacks were inevitable. Koenig ordered his men to dig in and prepare for a fight.

With the Italians bogged down at Bir Hacheim, the Afrika Korps thundered toward the vital supply routes behind the Gazala Line. At the Retma Box east of Bir Hacheim, the German 90th Light Division struck the British 7th Motor Brigade, which was shattered by the attack and retreated to the northeast. With the Retma Box in Axis hands, a British collapse along the southern end of the Gazala Line seemed within reach.

But the fight would be far from an easy victory. As the 15th Panzer Division rolled north, it abruptly ran into the 4th Armored Brigade in a surprise encounter that neither side expected. At the outset of the fight, the Germans took the worst of it, then pressed on, only to run into the stout wall of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment. The regiment was equipped with American M3 Lee tanks that, using British pattern turrets, were known as the Grant. The Grant’s 75mm main gun made it a formidable adversary for Rommel’s panzers.

British tankers methodically destroyed vehicle after vehicle, sending the Germans reeling in confusion. Even Rommel was shocked by the ferocity of the British defense. “The advent of the new American tank tore great gaps in our ranks,” he confessed. The men of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment had succeeded in stopping an entire Panzer division cold.

But the weight of numbers, and quick maneuvering, turned the tide. With the British fixed in position, elements of the 21st Panzer Division executed a wide turning movement, falling on the enemy’s exposed left flank. With their flank caved in, the men of the 3rd Regiment retreated, German tanks close on their heels.

The momentum of the fight had turned in favor of the Germans. As the Afrika Korps pushed north, it wrecked the rest of the 4th Brigade, consisting of the 8th Hussars and the 5th Royal Tank Regiment. On their far right, the Germans experienced even greater success, where the 90th Light Division smashed startled British columns, in the process capturing Maj. Gen. Frank Messervy, the commander of the 7th Armored Division.

With his 7th Armored Division shattered, XXX Corps commander Lt. Gen. Charles Norrie ordered reinforcements south in a desperate bid to blunt Rommel’s attack. The 22nd Armored Brigade made a bold delaying attack into the teeth of the Afrika Korps but paid a heavy price in the process, losing 30 tanks in as many minutes.

As the day progressed, British commanders were able to begin coordinating their efforts against the unexpected onslaught and by that afternoon launched a counterattack. The 22nd Armored Brigade, after regrouping, pushed back against the head of the German columns. Simultaneously, the 2nd Armored Brigade attacked from the east in the hope of striking Rommel’s right flank.

What ensued was a quintessential armored battle in the desert wastes of North Africa, and the British, organized after a day of confusing defeats, began gaining ground on the Afrika Korps. Some of the British armor succeeded in working their way into the German rear echelons, wreaking havoc among vulnerable supply trucks.

By little more than grit and outright determination, British forces had at last brought the fast-moving Afrika Korps to a screeching halt. Although the Axis attack had gone remarkably well, British soldiers had given a good accounting of themselves, forcing the Afrika Korps to pay dearly for every inch of ground.

The Germans had driven deep into the British rear areas and secured the vital supply roads of the Trig Capuzzo and Trig el Abd, but the Ariete Division had failed to reduce the French garrison of Bir Hacheim. Moreover, British forces stationed in the northern reaches of the Gazala Line remained largely untouched. The Afrika Korps was trapped to the east of the British minefields, and the long Axis supply line followed a circuitous course far to the south and east of Bir Hacheim.

Despite the stunning tactical victories in the drive around the British flank, Rommel had lost a third of his tanks during the ferocious fighting. Rommel later confessed that he was seriously worried that evening. “Our plan to overrun the Gazala Line had misfired,” he wrote, noting that the opposition was stronger than he had expected.

On May 28, Rommel ordered further attacks to the north in the hope of reaching the coast and cutting off British troops occupying the Gazala Line. His forces, though, were badly hamstrung by a woeful lack of fuel and supplies. Yet by the end of the day his Italian allies had achieved a small miracle. The Trieste Division, threading its way north of Bir Hacheim, succeeded in opening a secure path through the minefields that when widened facilitated the rapid resupply of the Afrika Korps.

Rommel reorganized his forces the next day, placing the Afrika Korps, 90th Light Division, and the Ariete Division between the Trig Capuzzo and Trig el Abd. The position not only cut off resupply to the beleaguered garrison of Bir Hacheim but also served as an ideal jump-off point for a renewed attack against the Eighth Army. Rommel shielded his position with an impressive array of artillery and antitank guns, and planned to regroup for a further push once he was ready. He also entertained hope that the British would suffer heavy losses attacking the Axis defenses.

Ritchie, aware that Rommel’s forces were pinned against the minefields of the Gazala Line, was quick to pounce for the kill. As Rommel edged back to a stronger position, Ritchie ordered a series of attacks against Axis forces, but the attacks were largely uncoordinated and beaten off with heavy losses on both sides.

The British dealt Rommel another surprise on May 30. During the swift fighting of the previous four days, an isolated British position at the Sidi Muftah Box, manned by the 150th Brigade, had been bypassed by Axis forces. The position, though, threatened Rommel’s new supply lines through the minefields. Swinging his troops to the west, Rommel increased pressure on the isolated British troops. Fierce fighting ensued and initial German attacks against the position were repulsed.

British diversionary attacks were launched the next day to relieve pressure on the Sidi Muftah Box, but were once again uncoordinated affairs that were handily brushed aside by the Germans. Rommel, growing frustrated with the stubborn resistance offered by a single British brigade, threw the 15th Panzer Division and 90th Light Division against the box and succeeded in seizing part of the position.

“On the afternoon of May 30 I personally reconnoitered the possibilities for an attack on the [Sidi Muftah Box] and detailed units of the Afrika Korps, 90th Light Division, and the Italian Trieste Division for an assault on the British positions next morning,” Rommel wrote afterward. “The attack was launched on the morning of May 31. German-Italian units fought their way forward yard by yard against the toughest British resistance imaginable.”

“On the following day the defenders were to receive their quietus,” he continued. “After heavy Stuka attacks, the infantry again surged forward against the British field positions. Piece by piece the elaborate British defences were won until by early afternoon the whole position was ours.”

Rommel renewed his attack on June 1. After a combined aerial and artillery bombardment, the Desert Fox ordered an all-out attack on the Sidi Muftah Box. Rommel’s units overran the box, which was the scene of desperate hand-to-hand fighting. The surrender netted Rommel 3,000 prisoners. Rommel then turned his attention to the French at Bir Hacheim, dispatching the 90th Light and Trieste Divisions to reduce the stronghold once and for all. However, the French troops repulsed both divisions and maintained their stubborn grip on Bir Hacheim.

Ritchie persisted in the belief that Rommel had placed his army in an untenable position. Rejecting Auchinleck’s advice to attempt a flanking maneuver to the south, Ritchie once again planned to throw his troops directly into the face of the Afrika Korps, which he was certain was on the verge of collapsing. Ritchie initiated Operation Aberdeen on June 5 by launching a major attack on the Axis position between the Trig Capuzzo and Trig el Abd. The enemy stronghold, which was the scene of some of the bloodiest fighting in North Africa up to that point, came to be known as the Cauldron.

Following on the heels of a massive artillery bombardment, the 22nd Armored Brigade pushed westward into the Cauldron with 150 tanks. The attack initially went well, plunging nearly two miles past outer German positions. But with little warning, the situation turned disastrous. Far too late, it was realized that Rommel had moved his main line back to avoid the initial bombardment. The 22nd Brigade had inadvertently advanced into a trap.

The Germans opened up on the exposed tankers with a deadly combination of artillery and antitank fire that left the battlefield littered with burning British armor. The British tankers frantically wheeled to the rear and abandoned the fight. To the north, the 32nd Tank Brigade fared even worse. It ran headlong into a line of blazing antitank guns fielded by the 21st Panzer Division. The brigade lost 50 of its 70 tanks in a matter of minutes. A number of other British regiments were left stranded inside the Cauldron.

Rommel immediately ordered a counterattack. He hurled the combined armor of the Afrika Korps and the Ariete Division at the withdrawing British forces. The sudden appearance of Axis armor threw the British units into great confusion. They withdrew into the defensive boxes at Knightsbridge and El Adem. The Axis troops had once again repulsed a poorly coordinated British attack with heavy losses. The Germans focused their attention on isolated British units that had been cut off during the hasty retreat. The Germans destroyed half a dozen Commonwealth units while mopping up the following day.

With the Eighth Army again on his heels, Rommel set his sights on the French garrison at Bir Hacheim, which had been a nettlesome tactical distraction for more than a week. On June 7, Rommel reinforced his infantry around Bir Hacheim, bolstering the assault force with tanks from the 15th Panzers. True to form, Koenig’s troops stoically defended the position, once again beating off Rommel’s forces.

For three more days, the heroic Free French defenders of Bir Hacheim waged a desperate battle against vastly superior forces. To Rommel’s frustration, Koenig repeatedly refused offers of an honorable surrender. But a succession of fierce German attacks increasingly seized portions of the position, tightening the noose around Koenig’s exhausted troops. British attempts to relieve the bastion proved tardy and ineffective.

Ritchie authorized an evacuation on June 10. Koenig’s soldiers, exhausted, hungry, and low on ammunition, slipped out of Bir Hacheim under cover of darkness. To their consternation, the Germans found the box empty the following day. Of Koenig’s 3,600 men, approximately 2,600 reached British lines.

The northern Gazala Line was still in British possession, but then bent back sharply to the east roughly along the Trig Capuzzo. The majority of Eighth Army’s armor, which still outnumbered Rommel’s panzer force, was largely concentrated between Knightsbridge and El Adem. Ritchie had also been reinforced by two fresh brigades of Indian troops. Although his forces still held an overall numerical advantage, the army’s top brass was gripped by a palpable lack of aggressive initiative. On the front lines, repeated battlefield drubbings had left Commonwealth troops badly demoralized.

Rommel had every intention of exploiting the weaknesses. On June 12 Axis forces opened a drive against the British stronghold east of Knightsbridge. The attack was spearheaded by the 15th Panzers supported by the Trieste Division. On the German right, flank security was offered by the 90th Light Division. The 21st Panzers remained in the Cauldron as a reserve.

When the 15th Panzers opened the fight with the British 2nd and 4th Armored Brigades, the attack faltered until Rommel personally arrived on the scene to spur on his tankers. A furious fight developed in which both sides suffered a severe mauling. Rommel, though, was disinclined to engage in a slugging match. Unknown to the British, he brought up the 21st Panzer Division, which unexpectedly appeared to the west and drove into the British right flank.

Allied defenses crumbled and British tank crews executed a desperate fighting retreat to the north. All told, the British lost a staggering 138 tanks in a few hours of heavy fighting. They were also left in a tight spot. Elements of the 21st Panzer had moved just west of Knightsbridge, and units of the 15th Panzer were just outside of El Adem. Rommel had the cream of the Afrika Korps in position by nightfall to deliver a deadly blow to the Eighth Army.

In the morning, the German juggernaut pressed forward. Rather than confront the Knightsbridge Box head on and risk a lengthy reprise of the Bir Hacheim siege, Rommel sent the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions in a mad dash that bypassed the flanks of the British position, pressed north toward the coast, and threatened to cut off all escape routes for British troops manning the northern Gazala Line. The crucial Knightsbridge Box was abandoned. But in large measure due to stubborn resistance offered by the 201st Guards Brigade, the Afrika Korps was unable to press through to the coast by nightfall.

The two days of fighting had decimated Eighth Army’s armored brigades and left much of the army in grave danger of being cut off and surrounded by the Germans. Ritchie came to the conclusion that a major retreat was necessary to save the battered remnants of the army, and ordered the 1st South African Division and the British 50th Division to evacuate the Gazala Line and head east along the Via Balbia, the main coastal thoroughfare.

Ritchie rallied what was left of his forces in a line running from Tobruk southeast to Belhamed, which was home to a vast supply dump. The skeletal remnants of the Eighth Army were no match for the Afrika Korps, which continued its unrelenting assault on June 15. In just two days, Rommel’s panzers pried loose the last British defenders southeast of Tobruk, and Ritchie’s army was in flight toward the Egyptian border.

The vital port of Tobruk, the greatest prize in North Africa, was at that point completely cut off. Far from inclined to squander time on yet another lengthy siege of the city, Rommel planned to launch a devastating attack on the town’s garrison; then he planned to focus anew on the Eighth Army.

In the predawn hours of June 20, German infantry operating under a massive artillery and air bombardment opened avenues of attack through the outer British defenses. The tanks of the 21st and 15th Panzer Divisions then poured through the gaps, pressing for the city center and its strategic harbor. Despite a desperate fight mounted by the city’s outmatched defenders, serious resistance was all but over by nightfall. Early the next morning, Maj. Gen. Hendrik Klopper, the South African commander at Tobruk, ordered his troops to surrender.

The fall of Tobruk was a catastrophe of the first order, as well as a crowning disgrace to the British Army’s devastating defeats of the previous three weeks. With the capture of the city, the front lines shifted east into Egypt itself, and Rommel’s seemingly invincible Afrika Korps was poised to strike directly for the Suez Canal. There was little in its path except the wrecked shell of the Eighth Army.

Although awarded a field marshal’s baton for his capture of Tobruk, Rommel’s ultimate goal of a stunning invasion of eastern Egypt would never materialize. On June 25, Auchinleck relieved Ritchie and took direct command of the Eighth Army. For the succeeding three days, he fought a costly delaying action at Matruh before falling back to a newly constructed defensive line across the Egyptian desert that centered on the inconspicuous village of El Alamein. Owing to a crippling supply shortage, Rommel was forced to settle in for a lengthy waiting game. In the autumn of 1942 the Afrika Korps was destined to once again fight a reinforced and rejuvenated Eighth Army that possessed a keen thirst for vengeance.

The bitterly fought North Africa campaign would end in crushing defeat for Axis forces; however, the epic fight in the desert expanses of Cyrenaica and Rommel’s masterful destruction of the Gazala Line had earned the resolute German general a place in the pantheon of World War II’s most legendary field commanders. Even British Prime Minister Churchill offered grudging admiration for the Desert Fox. “We have a very daring and skillful opponent against us, and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great general,” Churchill had told the House of Commons in early 1942. It was a spot-on assessment.