By Nathan N. Prefer

In the months that led up to Doolittle’s raiders assembling to strike back at Tokyo, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was deeply concerned. Ever since December 7, 1941, the day of the Japanese Pearl Harbor attack, the United States had suffered one defeat after another.

In addition to the near destruction of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, American outposts at Wake Island and Guam had fallen to the enemy, the gallant American-Filipino defense of the Philippines was crumbling fast, and there seemed no way to stop the Japanese juggernaut advancing toward America’s west coast.

America’s allies were impotent, the British and Dutch military forces having been either annihilated or pushed aside throughout the Far East. Nowhere was there a success to present to the frightened American people.

President Roosevelt had a special pride in the United States Navy, having once been an assistant secretary of the Navy, and ever since then had considered himself a “Navy man”—much to the chagrin of his Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall. The president was worried that “his” Navy was not doing anything about these steady enemy advances.

During a visit by British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill to the White House, FDR complained that the Navy had gone out with orders to fight the Japanese but had turned back after only a few hours of searching for the enemy.

Roosevelt’s dissatisfaction resulted in a shakeup of the Navy high command, placing Admiral Ernest J. King in overall command and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz in command of the Pacific Fleet. Yet even then, the Navy was able to launch only a few hit-and-run raids on Japanese outposts in the central Pacific.

These would not suffice. There was a growing feeling within the Roosevelt administration that the American people needed something more, something dramatic—a strike at the enemy that would bring the scent of victory, even if the strategic value was nil.

Francis C. Low Proposes an Audacious Plan: Army Twin-Engine Bombers on a Navy Carrier

Roosevelt had been seeking such a strike ever since Pearl Harbor. Shortly after Japan’s surprise raid, he had asked the Army Air Force Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold if there was any possibility of launching a bombing raid on the Japanese homeland. General Arnold was tasked to investigate the possibilities and to come up with some way to make such a raid happen.

But the rapid advance of the Japanese soon eliminated any Pacific bases from which American planes could launch such a raid. The president continued to seek out possibilities. He asked Admiral King if it was possible for American Army Air Forces bombers to take off from aircraft carriers. Admiral King’s operations officer, Captain Francis C. Low, believed it was possible, and was he ordered to test his theory. Thus was born the First Special Aviation Project—popularly known today as the Doolittle Raid.

Captain Low had recently visited the Norfolk Naval Base in Virginia. While there, he had seen something that intrigued him. There were Army pilots practicing bombing runs on an outline of an aircraft carrier’s deck that was painted on the ground. The idea, of course, was for Army pilots to be prepared to attack enemy aircraft carriers. The outline was also used to train Navy pilots for carrier landings and takeoffs.

But Captain Low saw something else. He wondered, “If the Army has some twin-engine bombers with a range greater than our [Navy] fighters, it seems to me a few of them could be loaded on a carrier and used to bomb Japan.”

Captain Low, a submarine officer and not a pilot, waited with trepidation as his commander, not known for his mild temper, thought it over. But to his surprise, Admiral King replied, “You may have something there, Low. Talk to Duncan about it in the morning. And don’t tell anyone else about this.” “Duncan” was Captain Donald B. Duncan, Admiral King’s air operations officer and a veteran pilot.

How the B-25 Mitchell Became the Bomber of Choice for a Tokyo Raid

The next day, January 11, 1942, Low and Duncan discussed the idea. They determined that there were two main questions to be answered: could an Army Air Forces medium bomber land on an aircraft carrier, and could it take off with a heavy load of fuel and bombs?

Donald B. Duncan, a 1917 Naval Academy graduate, knew immediately that there was no way an Army bomber could land on an aircraft carrier. The deck was simply too short to land such a large plane and, even if it could be landed, the carrier’s elevators were too small to lower the plane below decks. Nor were the tails of the Army aircraft strong enough to take the shock of the aircraft carrier’s arresting gear. But whether those bombers could take off from a carrier, Duncan was not sure.

Duncan immediately began to research the answer. He studied Army aircraft manuals, checked records to see if Army planes had ever taken off from an aircraft carrier, and sought historical records for any information. Five days later he produced a handwritten, 30-page report that concluded that there was only one bomber aircraft that might possibly take off from an aircraft carrier: the North American B-25 “Mitchell” medium bomber.

Named for Army Air Service Brig. Gen. William Lendrum “Billy” Mitchell, who upset military doctrine and tradition by insisting that aircraft could and should be used to attack enemy battleships, and that the Navy should invest in aircraft carriers, not capital ships (he was court-martialed in 1925 for his insubordination), the B-25 was considered the easiest bomber to fly and land. It was stable but maneuverable, allowing the pilot to pay attention to what was going on beyond the aircraft during combat. It had entered Army Air Forces service in 1940, and during the war would go through eight official and several “unofficial” adaptations.

Powered by two Wright R-2600-29 Double Cyclone 14-cylinder radial 1,850 horsepower engines, the B-25 had a maximum speed of 275 miles per hour and a service ceiling of 24,000 feet. It also had a range of 1,500 miles, and during the war it became increasingly armed with additional machine guns, and briefly even a 75mm gun placed in the forward nose to strafe enemy bases. Smaller than the B-17 “Flying Fortress” and B-24 “Liberator,” it carried a crew of five.

Captain Low worked with General Arnold, who was as anxious to respond to the president’s request as Admiral King. With the aircraft question settled, the next step was to find a commanding officer for the First Special Aviation Project. The man selected was short, balding James Harold Doolittle. He was born in Alameda, California, on December 14, 1896. While attending the University of California, he enlisted in the Army Reserve and by 1920 had earned a commission in the aviation section of the Signal Corps.

James Harold “Jimmy” Doolittle

During World War I, Lieutenant Doolittle was a flight instructor. After the war, in 1922, he made the first transcontinental flight in under 24 hours, earning him a reputation as a distinguished flyer. By 1930, he had become bored with military flying and left the service to enter private industry.

As a civilian, Doolittle won the coveted Thompson Racing Trophy and worked as a test pilot, during which he experienced several crashes and parachute jumps from various aircraft. But Doolittle was not just a daredevil; in between air races and crashes, he was one of the first to earn a doctorate in aeronautical sciences from the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This led him to the development of high-octane fuel, which was to prove of critical importance in the coming war.

But after a decade with Shell Oil Company, the approach of a new world war prompted him to return to the Army Air Forces in July 1940. By the following year he was a lieutenant colonel on General Arnold’s staff.

One January morning in 1942, Doolittle was called into the general’s office and briefed on the possibilities of Army bombers flying off Navy carriers to bomb Japan. Asking for time to consider the possibility, Lt. Col. Doolittle went to his office and studied the question. He too decided that the only viable aircraft was the B-25 medium bomber, properly modified.

Upon return to General Arnold’s office, he presented his findings. Arnold then asked if he knew someone who could organize such an operation, and Doolittle volunteered.

Why Doolitte’s Raiders Planned to Land in China

The Navy was also preparing to implement the plan. It had been decided that the USS Hornet would be the best aircraft carrier to launch the raid. Since the Hornet was about to arrive on the East Coast after operations in the Pacific, it was hoped that some experimental flights of B-25s from her decks could be conducted. Meanwhile, Captain Duncan flew out to Hawaii to organize the task force that would carry the First Special Aviation Project to war.

The thorny problem of landing returning bombers on aircraft carriers could not be resolved. But then a solution appeared: Doolittle’s B-25s would not have to return if, after bombing Japan, they could continue on and land in China. This solved another issue: the Navy’s task force would be dangerously exposed while approaching Japan to launch the bombers, and they would have to return as quickly as possible, representing as they did the only remaining U.S. naval presence in the Pacific at the time.

So strict was the secrecy shielding the mission to bomb Japan that in a meeting with the president on January 28, 1942, the Chiefs of Staff, not all of whom knew of the project, did not mention it at all, referring only to bombing Japan from Chinese bases. Roosevelt was not informed of the plan until later in the year, even though he continued to push for an immediate bombing of Japan proper.

Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Doolittle set out for Wright Field in Ohio to begin preparing for his new command. At the same time, Captain Duncan flew to Norfolk, Virginia, to tell Captain Marc A. Mitscher, commanding the USS Hornet, that he was going to have three B-25s brought aboard to do trial takeoffs from the carrier. Captain Mitscher, a future admiral, knew better than to ask questions.

The three B-25s to be placed aboard the Hornet were led by 1st Lt. John F. Fitzgerald. Each plane had only a two-man crew—a pilot and co-pilot—who had spent some days practicing on that same mock field at Norfolk that had been observed by Captain Low weeks earlier.

One of these B-25s fell out with engine failure before the trials. The other two were hoisted aboard the Hornet, and Captain Duncan discussed details of the trial, without revealing the mission itself, with Captain Mitscher. Mitscher, himself a naval pilot, understood the risks involved.

A Successful Trial Flight, but Many Questions Remained

The following day, February 2, the carrier sailed from Norfolk out of sight of land. The crew of two B-25s, piloted by Lieutenants Fitzgerald and James F. McCarthy, were ordered to man their planes. Fitzgerald later remembered that he was surprised to find that he had about 500 feet of usable deck space available and that his plane’s airspeed indicator, revved up and with the brakes full on, needed only a score more miles of airspeed to take off.

The takeoff went surprisingly well, and Fitzgerald was airborne with room to spare; McCarthy followed without complications. Both pilots flew back to Norfolk without knowing why they had just risked their lives.

The flight trial had been successful, but questions remained. Both planes had light fuel loads, only two rather than five crewmembers, and carried no bombs or extra fuel tanks. Yet Captain Duncan was satisfied that a fully crewed and loaded B-25 could take off from an aircraft carrier at sea.

Doolittle agreed with Duncan, provided that the carrier was headed into the wind at a speed above 20 knots. There was some doubt, however, if while carrying 20 B-25s the carrier would have enough deck space left to safely launch those same bombers.

“The Special B-25B Project”

Doolittle was kept busy determining which modifications would be necessary to enable the bombers to reach Japan from the carriers and then fly on to China. He made drawings of those modifications for the engineers at Wright Field and plotted the size and number of additional fuel tanks that would need to be installed in each bomber.

He then met with Brig. Gen. George C. Kenney, later to lead the Fifth Army Air Force in the southwest Pacific, to explain what he needed for what he termed “the special B-25B project” without telling him the reasons behind his demands. Much in the way of new equipment was necessary, including new plumbing to implement the additional fuel tanks, and new bomb shackles for the modified bomb load.

The fuel tanks proved the biggest problem. Eventually, a 265-gallon steel tank was specially manufactured by the McQuay Company, but this proved problematic and was soon replaced by a 225-gallon tank manufactured by the United States Rubber Company of Mishawaka, Indiana.

Still, problems remained. The tanks leaked, usually at the connections between tanks and lines. Repairs solved most but not all these problems. A second tank of 160-gallon capacity was installed above the bomb bay. Again, leaks were a problem, increasing the fire hazard, but modifications and repairs reduced the risk to acceptable levels.

The lower gun turret was removed and replaced with a 60-gallon tank that was to be refueled during flight by a gunner from 10 five-gallon fuel tanks carried in the rear compartment. Altogether, the planes would carry 1,141 gallons (9,527 pounds) of fuel per aircraft, of which 1,100 would be available. Under severe time constraints, the planes were accepted with these remaining difficulties and flown off to Florida.

Who Would Be the Target for Doolittle’s Raiders?

Next, Doolittle needed targets. For this, he approached Brig. Gen. Carl (“Tooey”) Spaatz, General Arnold’s deputy for intelligence. He asked for the target folders on the most important industrial targets in Japan. Again, he did not reveal why he wanted these, and General Spaatz, who later commanded the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, did not ask.

Ten such targets were offered. These included the cities of Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe, Nagoya, and six smaller cities. The actual targets included iron, steel, magnesium, and aluminum plants, petroleum refineries, and shipbuilding facilities.

In Washington, the president was still pressing for some action against Japan itself. He constantly inquired of General Arnold and Admiral King about a plan to strike at the heart of Japan. He was interested at this time in an idea to strike Japan with heavy bombers flying from Mongolia.

General Arnold explained that there was no way heavy bombers could operate from Mongolia without the permission of the Soviet Union, which was then a neutral in the Pacific War. Arnold also explained that the best alternative was basing bombers in China and striking Japan from there, making no mention of the Doolittle project.

That project was gaining momentum. Having worked out to the best of his ability the mechanics of the project, Doolittle now addressed the matter of personnel. He needed trained crews by April 1, 1942, his deadline for the operation.

Doolittle Seeks Volunteers

As was his practice, he sat down and wrote a memorandum to himself in which he outlined what he needed for the coming attack. In this memorandum, titled “B-25 Special Project,” he outlined his objectives and requirements for success. The “purpose of this special project is to bomb and fire the industrial center of Japan,” he wrote.

The method was “to bring carrier-borne bombers to within 400 to 500 miles of the coast of Japan, preferably to the south-east.” The planes were to fly to their targets by following rivers or other landmarks. Bombing was to be simultaneous. After bombing, the planes were to fly to Chinese airfields at Chuchow, Lishui, Yushan or Chienou—fields that were inland of the Chinese coast and not under Japanese occupation.

After refueling, the aircraft were to proceed to the major Chinese airfield at Chungking, 800 miles inland. From there, they would go on to whatever destination had been ordered. The greatest nonstop distance any plane would have to fly was 2,000 miles. Twenty-four B-25s would be included, six of them being “spares” in the event another plane malfunctioned. Each bomber carried two 500-pound bombs and up to 1,000 pounds of incendiaries.

Crews would be standard: pilot, co-pilot, bombardier-navigator, radio operator, and gunner-mechanic. Only volunteers with experience flying in the B-25B would be accepted. One crew member would be a competent meteorologist and another an experienced navigator. Chinese-speaking volunteers were eagerly sought.

Doolittle asked which Army Air Forces units were already flying the B-25B bomber. He learned that the 17th Bombardment Group, consisting of the 34th, 37th, and 95th Squadrons, was already flying this version at Pendleton, Oregon. So too was the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron. He had orders issued to transfer all planes and crews of these squadrons from Pendleton to Columbia Army Air Base in Columbia, North Carolina.

Word was passed that volunteers were needed for an extremely hazardous mission without giving details. En route to Columbia, the B-25Bs had the fuel tanks installed as designed by Doolittle.

The Problem with Doolittle’s Qualifications

Like the project itself, training needed to be kept secret. Eglin Airfield in the Florida panhandle was selected. Besides seclusion, Eglin was close to the Gulf of Mexico, which would provide the volunteers with practice in over-water navigation, an essential part of the coming project.

With his time divided between Wright Field, Washington D.C., and Eglin Field, Doolittle needed a good executive officer. He selected Major John A. “Jack” Hilger, commander of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron. Hilger would set up the training protocols at Eglin Field, assemble the aircraft, and train the team for the mission.

All three of the squadron commanders of the 17th Bombardment Group volunteered, but the commander, Lt. Col. William C. Mills, could not release them all, and only Captain Edward J. “Ski” York was transferred. The same spirit prevailed among the flight crews, and nearly all volunteered. The decision was left up to the three squadron commanders as to who was accepted. Soon, 24 crews were named, as well as sufficient ground crews, mechanics, armorers, and radio operators. These men were ordered to report to Eglin Field.

Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle was about to lead a flight of B-25B bombers to Japan, but he himself had never qualified to fly a medium bomber. He addressed this problem by giving up, albeit temporarily, his P-40 fighter aircraft to qualify on the B-25B.

Secrecy Above All Else

With crews and planes selected and finally assembled at Eglin Field, Doolittle confided in Major Hilger the mission’s objective and methods, to allow him to understand the nature and importance of the training he was about to oversee. Hilger suggested assigning a Navy flight officer to the training program, since the Army Air Forces had little understanding of the ways of the U.S. Navy. Captain Duncan had similar thoughts and had assigned a young Navy pilot, Lieutenant (later Rear Admiral) Henry L. “Hank” Miller. His participation in the mission would prove greatly valuable.

Lieutenant Miller’s arrival confused the crews even more. When asked why he was there, he replied that his mission was to teach them how to take off from an aircraft carrier. They were even more surprised when he added that he had never flown a B-25B before. This he rectified quickly by making several flights in the bomber.

Once familiar with the aircraft, Miller used a small auxiliary field to instruct the squadron leaders in carrier takeoffs. The Army pilots were skeptical but willing to learn. Soon, they were taking off within 350 feet into a 40-knot wind with a load of 31,000 pounds—2,000 pounds over the aircraft’s official load limitations.

Doolittle soon had his squadron organized. His executive officer was Major Hilger, Major Henry Johnson was the adjutant, and Captain “Ski” York the operations officer.

Gradually, as things began to come together, the staff was let in on the plans, objectives, and methods of the operation for which they were training. Secrecy remained a top priority.

Determined to lead the operation he had done so much to organize, Doolittle submitted himself to Miller’s training course. Army pilots, trained to use as much takeoff ground as they wanted, were shocked to learn that they had only about a football field’s length to gain airspeed, which in the Navy’s language was a mere 50 miles per hour! But they learned and soon achieved takeoffs at the required runway length and speed.

Bombing Tokyo with a 20-Cent Bombsight

Doolittle wanted his pilots to familiarize themselves with their aircraft and with flying during daytime and nighttime, as well as flying over water and land. He set 50 hours flying time as his goal, but continued modifications and repairs to the planes made this goal rarely achievable.

It was then that another problem arose. With the aircraft already carrying more than their official loads, some guns aboard the planes had to be removed. But that only invited attack. Captain C. Ross Greening, the squadron’s gunnery officer, came up with the solution. Broomsticks painted black would replace the guns in the tail section in hopes the sight of the dummy barrels would chase away Japanese fighters.

The next problem was the top-secret Norden bombsight used by American bombers. This highly secret bomb sight could not fall into enemy hands. But since the bombers were going to fly low over Japan to avoid detection and would be bombing by sight, they had no use for it, and they were removed from all the aircraft.

A makeshift bombsight, made of two pieces of aluminum and costing about 20 cents, replaced it. The bombardiers found that it actually worked much better at low altitudes than the Norden sight. Captain Greening also suggested removing the lower gun turrets, which were worked electronically and gave constant problems. Doolittle agreed, and the turrets were removed.

Then it was revealed that almost none of the gunners had ever fired a machine gun from an aircraft. Worse, most of the machine guns provided to the squadron were inoperable. It turned out that the guns had not been fully assembled before they were issued to the squadron. An ordnance expert from Wright Field had to be called in to fix that problem. But the delay prevented the gunners from practicing in the air, limiting practice to ground firing.

Doolittle had requested incendiary bombs for his upcoming mission. Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland provided him with 500-pound clusters of incendiaries that would scatter while falling, thereby covering a wider area. But the demolition bombs provided would not release from the bomb racks aboard the aircraft. This problem was eventually resolved, but it cost time in training and practice.

“Tell Jimmy to Get on His Horse”: Doolittle’s Raiders Prepare to Assault Tokyo

One thing the squadron did not have yet was a doctor. This matter resolved itself when Dr. (1st Lt.) Thomas R. White, a physician assigned to the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, volunteered for the assignment. But there was no room for a doctor in the planes.

To provide a physician while not taking any non-flying personnel, White volunteered to qualify as a gunner aboard one of the bombers. In fact, he not only qualified but scored second highest of all the gunners on the firing range. He was assigned to a crew.

Doolittle now had to resolve a personal issue. He had missed combat in World War I and had made no secret of the fact that he was determined to get into the fight in the present war. In March, he visited with General Arnold and updated him on the project’s progress. With the briefing over, he asked permission to command and lead the squadron into the raid on Japan. Arnold refused, citing his need for Doolittle on his staff in Washington.

The determined lieutenant colonel refused to accept “no” for an answer and launched into a diatribe to gain command of the project he had spent three months developing. His argument was eventually successful, and he received command of what would soon be known as “Doolittle’s Raiders.”

Racing back to Eglin Field to prevent General Arnold changing his mind, Doolittle got back to training. After one of the pilots became ill, Doolittle assigned himself as that pilot’s replacement. His crew would be co-pilot 1st Lt. Richard E. Cole, navigator 1st Lt. Henry A. Potler, bombardier Sergeant Fred A. Braemer, and engineer-gunner Sergeant Paul J. Leonard.

Training and repairs continued until the third week of March, when Admiral King sent a message to General Arnold, which read, “TELL JIMMY TO GET ON HIS HORSE.” Arnold called Doolittle with the message, which meant that the USS Hornet was ready to receive the planes and pilots for the mission. Ironically, planes and pilots were ordered to report to Alameda, California, Doolittle’s hometown, preparatory to boarding the Hornet. By this time there were only 22 planes left to depart, the others having become casualties of practice takeoffs.

Problems with the Aircraft

Even now, at the moment of departure, problems continued to arise. While the aircraft waited to be loaded at McClellan Army Air Field, California, they were to be tested to ensure that all planes functioned correctly.

Doolittle personally advised the base commander that certain tests were not to be conducted, and that the carburetors were not to be adjusted, since that had been done at Eglin Field to Doolittle’s satisfaction. But the staff at McClellan Field was still on “peacetime” routine, and the repairs and tests were delayed.

One of the pilots, Captain Ted W. Lawson, remembered, “I had to stand by and watch one of the mechanics rev up my engines so fast that the new blades picked up dirt which pockmarked their tips. I caught another one trying to sandpaper the imperfections away and yelled at him until he got some oil and rubbed it on the places he had just sandpapered.” It would take another phone call to General Arnold to straighten out these latest difficulties.

The aircraft, many of which still had unresolved problems, were then flown to Alameda Naval Air Station on San Francisco Bay, California. They were met by Doolittle and Captain York, who inquired of each crew if there had been any problems on the flight from McClellan. Any crew that reported problems was ordered to park their aircraft in a designated area. Those aircraft would be left behind. Doolittle then ordered those crews to board the Hornet, where they would serve as alternate crewmembers. The “good” aircraft were loaded aboard the carrier on April 1, 1942, precisely on schedule.

The next issue to confront Doolittle was space aboard the carrier. He had originally planned for 18 B-25Bs to be hoisted aboard but, after discussion with Navy officers, it was learned that only 15 would fit and still allow sufficient deck space for takeoff.

Task Force 16.2

Nevertheless, 16 B-25s were loaded aboard. Concerned that some of his men were still apprehensive about flying off a carrier, Doolittle said the 16th bomber would be flown off after the Hornet departed the naval station and sailed about 100 miles out to sea, to demonstrate once again the feasibility of the plan. This 16th B-25B would be flown off by two “spare” pilots aided by Lieutenant Hank Wilson.

Launched in 1940 as the second ship of the Enterprise-class of aircraft carriers, the USS Hornet displaced 20,000 tons, had space for up to 100 fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo bombers, and had of crew of slightly more than 2,000 officers and men. Normally the ship’s power lay in the average 80-85 planes it carried. But now, with all its own aircraft stowed away below decks and its deck crammed with Army bombers, the Hornet was defenseless. To protect the mission and the carrier, it would sail as a part of Task Force 16.2 under the command of Vice Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, Jr.

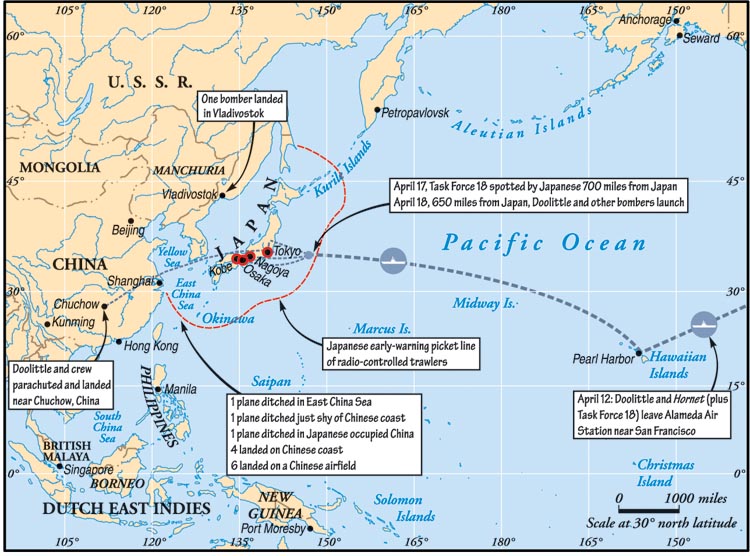

Task Force 16.2 included the carrier USS Enterprise (commanded by Captain George D. Murray, USN), a group of four cruisers under the command of Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, and two destroyer divisions under the command of Captain Richard L. Connolly, commander of Destroyer Squadron 6 (Desron 6). Two Navy oilers under Commander Houston L. Maples would accompany the task force part of the way to provide sufficient fuel for the return journey. The Hornet joined with Task Force 16.2 between Midway and the Aleutians on the morning of April 16.

By the next day, TF 16.2 had sailed to within a thousand miles of Tokyo and refueled from the two oilers before leaving the oilers and destroyers behind and racing toward Japan. Unknown to Doolittle, bad weather in China had prevented the fields in China, on which he expected to land and refuel, from being readied for his arrival.

It had already been calculated that to reach the Chinese airfields after the bombing of Japan, the B-25Bs would have to take off from the Hornet within 500 miles of the Japanese coast. Admiral Halsey had planned to launch a night attack at that distance on April 18. Thirteen planes would strike Tokyo, three others Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. Doolittle’s plane would lead and drop incendiaries on Tokyo to light the way for the following planes.

“To Col. Doolittle and Gallant Command, Good Luck and God Bless You.”

Most of the planes carried a small payload: three 500-pound bombs and one incendiary; Doolittle’s plane carried four of the firebombs. Even if they reached and successfully bombed their targets, the expected damage would be minimal. But the morale boost it would give the American people—and the shock to the Japanese who thought they were invulnerable—would be enormous.

The Japanese, however, had thrown a monkey wrench into the works. Unknown to the Americans, they had established a picket line of small craft well east of their own coastline. In the darkness of the morning of April 18, the radar aboard the leading ships indicated contacts ahead, some 700 miles from the enemy coast. TF 16.2 altered course to avoid the contact.

As dawn broke, the Enterprise launched scout planes to search ahead of the task force. Shortly before 6 am, they spotted a picket boat and reported that they thought they had also been seen by the Japanese. Soon after, another vessel was sighted, and Japanese radio signals were picked up, indicating that the task force’s presence was being reported to Japan.

The USS Nashville, one of the cruisers, sank the picket boat (and picked up survivors), but the cat was out of the bag. With surprise lost, Admiral Halsey had two choices. He could launch the planes knowing that they were 150 miles short of gaining the Chinese airfields, or he could turn back. After conferring with Doolittle, the decision was made to launch the Army bombers then and there.

He sent a message to Doolittle: “Launch planes. To Col. Doolittle and gallant command, good luck and God bless you.”

The Raiders Approach Tokyo

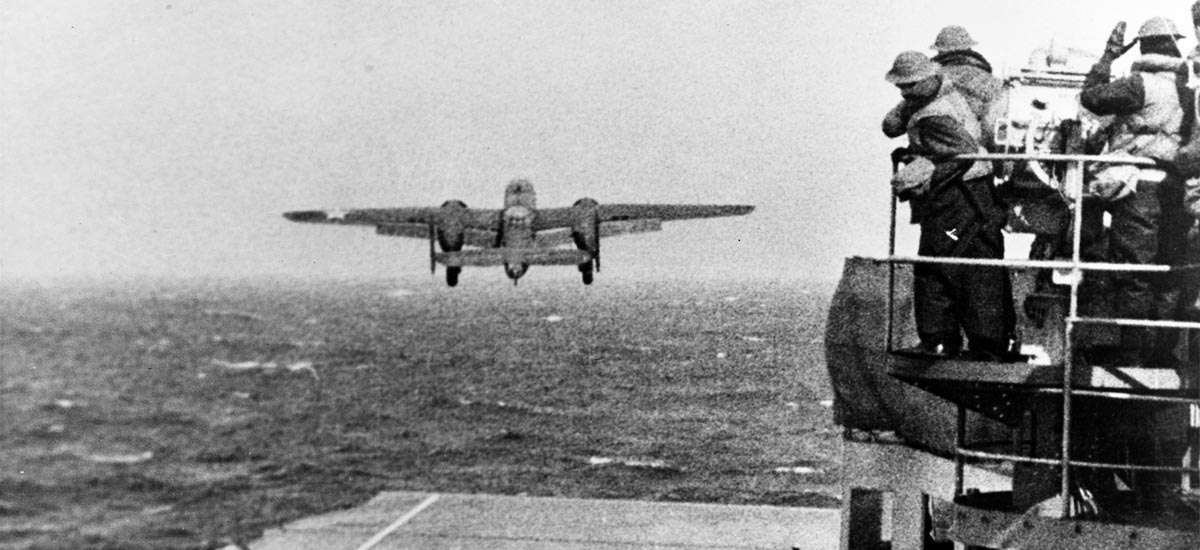

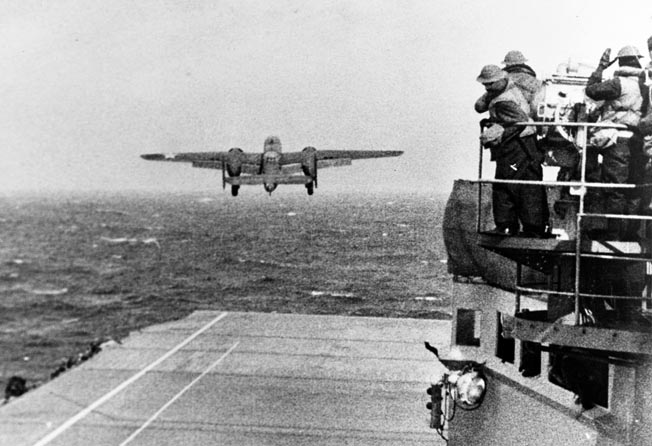

At 8:03 am, the Hornet’s skipper swung her into the wind and the first plane, piloted by Doolittle, took off some 623 miles from the Japanese coast and 668 miles from Tokyo. There was a strong wind and the sea was rough, causing many observers to fear that the planes would never make the takeoff. It was a close call but all 16 aircraft did make successful liftoffs, at three-minute intervals, helped by the Hornet’s 20-knot speed and headwinds blowing at another 30 knots.

What was supposed to be a clandestine night strike made within a specified flight distance was now a daylight strike against an alerted enemy with little hope of landing safely at the end of the mission. The last aircraft lifted off at 8:54 am, and a moment later, Mitscher changed the Hornet’s course for home. The 80 Doolittle Raiders were on their own.

As planned, the aircraft flew low over the Pacific, averaging barely 200 feet above the waves. The pilots and co-pilots took turns at the controls while the gunners closely watched the fuel gauges, filling up the third tank as necessary. Fuel consumption was on everyone’s mind, as they understood they did not have enough to reach the designated Chinese airfields. Ditching at sea or crash landing were the only available options.

During the flight, some of the crews flew over or near Japanese warships and Doolittle’s plane “flew directly under an enemy flying boat that just loomed at us suddenly out of the mist.” None of the Japanese encountered seemed to take any notice.

Once across the enemy coast, the pilots turned toward their individual targets. Again, many enemy aircraft were sighted, but none seemed to spot them. Nor was there any antiaircraft fire against the intruders. One reason was because Tokyo was, fortuitously, in the midst of an air-raid drill, and both civilians and the military believed the American aircraft were Japanese and part of the drill.

The other reason was the supreme confidence of the Japanese military hierarchy, which simply could not conceive of the despised Americans daring to attack Japan itself. Still, with the warnings provided by the picket boats, the Japanese 26th Air Flotilla, charged with guarding the eastern air and sea approaches to the home islands, was on full alert. Warships were also manned and prepared for any attack. Oddly, though, Tokyo did not alert the eight million residents that an attacking force was on its way.

The Tokyo-bound flight was roaring over the landscape at treetop level. Several Japanese warplanes flew by in the opposite direction, never breaking formation or giving any indication they knew the Americans were there. Dick Cole, Doolittle’s co-pilot, later wrote, “The people on the ground waved to us and it seemed everyone was playing baseball.”

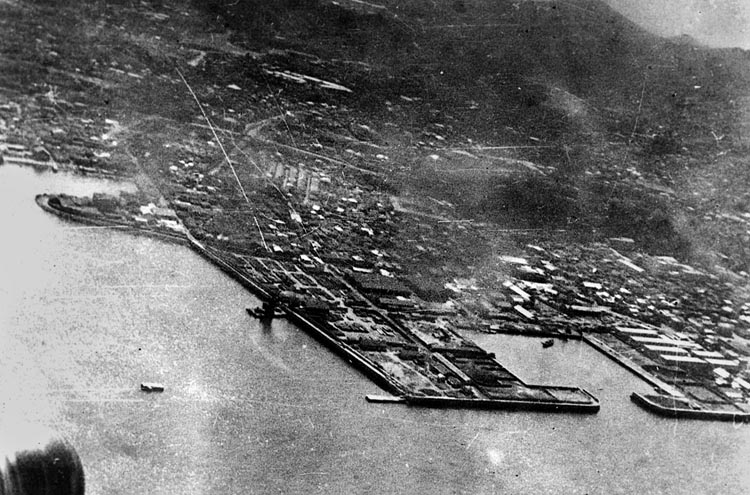

As he approached his target from the north, Doolittle lifted his plane to 1,200 feet and prepared to drop his bombs. Doolittle’s incendiaries, probably the first ever dropped on Tokyo, struck at 12:30 pm, Tokyo time. Each bomb held 128 four-pound bomblets that were designed to spread out over a wide area.

Once his bombs were away, Doolittle descended again to minimum height and headed for the sea. Despite the desires of his men, Doolittle had strictly forbidden any bombing of the Imperial Palace and any strafing with machine guns, fearing the repercussions should any of his men be captured.

As bombing raids go, this one was negligible in terms of death and destruction. Only about 50 homes and stores (as well as two schools and a hospital) were set on fire by the bombs from Doolittle’s plane. Two civilians died and 19 were wounded. Thirty-one unexploded bomblets were later found and recovered.

As Doolittle headed west and then south, away from the flaming structures below, antiaircraft fire rose up to pepper the sky; the planes in Doolittle’s wake had to brave the munitions coming up at them.

The high-explosive bombs the other Raiders dropped did far more damage than did Doolittle’s incendiaries. More buildings—including several steelworks—were hit and more civilians died. Japanese fighters were now up and chasing the later bombers, which barely escaped getting shot down.

The escape was much more difficult than the attack had been. Some planes, including Doolittle’s, ran into strong headwinds that further reduced the range of the planes and their limited gasoline supply. Others hit bad weather, which had the same consequences. But all 16 aircraft successfully bombed their targets and left Japanese air space, some with opposition from antiaircraft guns and fighters, others without any opposition at all.

What Happened to Doolittle’s Raiders After the Bombing Run

The planes flew toward China. Each was searching for some signal that there was a field prepared for them to land. None found any. Eventually 15 of the planes were forced to crash land; other crews had to parachute to safety.

Doolittle’s plane (40-2344) flew on until it was flying on fumes. Rather than crash land in the darkness in unfamiliar terrain, Doolittle and the crew decided to parachute to safety. They had been flying for 13 hours and had no idea of where they were or if the territory below was in friendly or enemy hands.

Doolittle remembered, “This was my third parachute jump to save my hide. It was impossible to see anything below, so all I could do was wait until I hit the ground. My concern as I floated down was about my ankles, which had been broken in South America in 1926. Anticipating a sudden encounter with the ground, I bent my knees to take the shock. When I hit, there wasn’t much impact. I had landed in a rice paddy and fallen into a sitting position in a not-too-fragrant mixture of water and ‘night soil.’”

After landing near Quzhou, he tried to contact friendly Chinese civilians, and after a few misadventures did find some who directed him to nearby Chinese military forces. First Lt. Travis Hoover led his crew (40-2292) in Doolittle’s wake most of the flight. He elected for a belly landing in a Chinese rice paddy near Ningbo, which caused no injuries. The men were rescued by friendly guerrillas who passed them on to safety.

Crew number three (in Whiskey Pete, number 40-2270) was under 1st Lt. Robert M. “Bob” Gray. After bombing dockyards, they flew into some antiaircraft fire but were not hit. Arriving over China, they bailed out southeast of Quzhou. The jump killed the gunner, Corporal Leland D. Faktor, and injured Lieutenant Charles J. Ozuk, the navigator. Friendly Chinese smuggled the other four survivors to safety.

First Lieutenant Everett W. “Brick” Holstrom led crew number four (40-2282) to Tokyo but they were attacked by enemy fighter planes and, with only one machine gun operable, were forced to dump their bombs into Tokyo Bay. They escaped the fighters and bailed out over Shangrao, where civilians led them to safety.

The fifth bomber (40-2283) was led by Captain David M. “Davy” Jones. This crew had problems from the takeoff when an attempt to top off the gas tanks had failed because the carrier was in “battle condition” and shut off all fuel lines. After bombing an oil storage tank, a power plant, and a manufacturing facility, they bailed out over Quzhou and were rescued.

One crew with the worst luck was in plane number six (The Green Hornet, number 40-2298) piloted by 1st Lt. Dean E. Hallmark. After bombing a steel mill in northeast Tokyo, they headed for China, where they ran out of gas; Hallmark decided to ditch his plane on the beach near Wenzhou. The landing was a hard one and Sergeant Donald E. Fitzmaurice and Corporal William J. Dieter drowned.

The three survivors—Hallmark, co-pilot Lieutenant Robert J. Meder, and Lieutenant Chase J. Nielsen, the navigator—were all injured. Friendly Chinese helped bury the casualties, but the survivors were later caught by the Japanese and became prisoners of war, suffering years of constant torture and beatings.

Bomber number seven (Ruptured Duck, number 40-2261) was piloted by Captain Ted W. Lawson, who wrote of his experiences in a best-selling book titled Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. This crew also bombed factories in Tokyo and ditched on the Chinese coast, suffering severe injuries. Thanks to Chinese civilians, all returned safely to the United States. Interestingly, Lieutenant White, the doctor-turned-gunner who flew in plane 15, was instrumental in saving Captain Lawson’s life by amputating his infected leg.

Plane number eight (40-2242), flown by Captain Edward J. “Ski” York, the squadron’s operations officer, experienced engine trouble that burned more fuel than was planned. Once his bomb load was gone, he had to make a decision. He could not make the Chinese coast, and a landing in Japan was unthinkable. Despite orders to the contrary, York headed for the Soviet Union, landing at a field near Vladivostok. Crew and plane were interned for 14 months before they “escaped” to Iran.

First Lieutenant Harold F. “Doc” Watson’s plane nine (Whirling Dervish, number 40-2303) bombed the Tokyo Gas and Electric Company and then bailed out over Nanchang where they were rescued.

The tenth plane (40-2250) was commanded by 1st Lt. Richard O. “Dick” Joyce, who bombed the Japan Special Steel Company and a precision-instrument factory. Despite antiaircraft fire, they escaped unscathed and bailed out safely near Quzhou.

The squadron’s gunnery officer, Captain C. Ross Greening, led crew number 11 (Hari Kari-er, number 40-2249). After bombing docks, oil refineries, and warehouses they were attacked by enemy fighter planes. The gunner believed that he shot down one of the aerial pursuers. They also escaped and bailed out over Quzhou where they were rescued.

Plane number 12 (Fickle Finger of Fate, 40-2278) was under 1st Lt. William M. “Bill” Bower. It first flew near a group of enemy fighters but was not attacked. Next, the crew found their primary target, the Yokohama Dock Yards, protected by barrage balloons. They dropped bombs on the Ogura refinery, two more on factories, and a large warehouse. They also reached China and bailed out near Quzhou.

One of Bowers’ crewmen, bombardier Sergeant Waldo J. Bither, had a close call. As he was preparing to bail out, his parachute caught on something and opened inside the plane. Of all the men on the Doolittle Raid, it turned out that Sergeant Bither was the only one who had training in packing a parachute. This he did quickly and made a successful jump.

Being number 13 (The Avenger, number 40-2247) didn’t bother 1st Lt. Edgar E. McElroy, the pilot. After bombing Yokohama dry docks and shipping in the harbor, this crew flew on to China and bailed out near Nanchang. Chinese civilians took them to the city of Poyang, where the population of 30,000 feted them as heroes.

The squadron’s executive officer, Major John A. “Jack” Hilger, flew plane number 14 (40-2297), which bombed the Mitsubishi aircraft plant in Nagoya. Like the others, they bailed out over China (near Shangrao) and were brought safely to join several other crews.

First Lieutenant Donald G. Smith piloted plane number 15 (TNT, number 40-2267), whose gunner was Lieutenant (“Doc”) Thomas R. White. This crew decided to ditch in the ocean, but all survived unhurt. The major loss was Doctor White’s medical kit when the raft overturned. They were picked up by a Chinese boat (“junk”), and after evading Japanese patrols, arrived at Chuchow, where Dr. White learned of Captain Lawson’s plight and went to his aid.

Plane number 16 (Bat Out of Hell, number 40-2268) was another unlucky ship. Piloted by 1st Lt. William G. “Bill” Farrow, it had injured a sailor aboard the Hornet during takeoff when he slipped under a propeller and had an arm sheared off. Farrow’s target was Nagoya, where the plane was attacked by enemy fighters. They reached the Chinese coast in darkness and fought a weather front. A break in the clouds revealed a city below, which they identified as Nanchang, known to be in enemy hands. But with no gas left, they had no option.

After bailing out near Ningbo, they were quickly captured, and like the crew of plane six, suffered constant torture at the hands of the Japanese until the end of the war. Of the eight men captured in planes six and 16, all suffered torture, starvation, solitary confinement, and constant beatings.

Three of the prisoners, Lieutenants Dean E. Hallmark, William G. “Bill” Farrow, and Sergeant Harold A. Spatz, the latter the gunner on Bat out of Hell, were executed by the Japanese for “war crimes.” The remaining four, starved, malnourished, and near death, were rescued at the war’s end.

Aftermath of the Doolittle Raid

Critics of the raid have said that it achieved nothing of military value; the bomb damage was easily and quickly repaired. But what they miss is the fact that the United States had struck a blow at the very heart of Japan itself, something that Japanese military leaders believed could never happen, and had raised American military and civilian morale. The string of unbroken victories by the Japanese appeared broken, even if only temporarily.

An important result of the raid was the embarrassment it caused the senior Japanese military leadership. It was unthinkable for them that Tokyo, the home of their honored emperor, was bombed by an enemy most of them despised. They went to great lengths to minimize the raid to their civilian population.

But the most important result was that the raid settled a dispute within the Japanese high command. The Japanese Naval General Staff wanted to wage their war in the South Pacific, attacking Australia and cutting its communications with the United States. Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto, leader of the Japanese Combined Fleet, wanted a decisive naval battle to knock the American Navy out of the war once and for all.

A successful battle would destroy the offensive power of the U.S. Navy, permit more conquests, and secure those already in Japan’s possession. He was convinced that his plan to trap the American fleet near Midway would accomplish this. He argued, correctly, that the Doolittle Raid could only have come through what he termed the “keyhole” at Midway, and that more such attacks could be expected.

His plan to capture Midway and destroy the U.S Pacific Fleet, then, was the only sensible option for Japan. The Doolittle Raid won over the opposing Japanese military leaders, and the Midway operation took top priority from that point on.

But at Midway, less than two months later, it was the Japanese fleet, not the American fleet, that was nearly des-troyed, thanks in no little part to the gallant fliers of the First Special Aviation Project, proudly known after April 1942 as “Doolittle’s Raiders.”