By Michael D. Hull

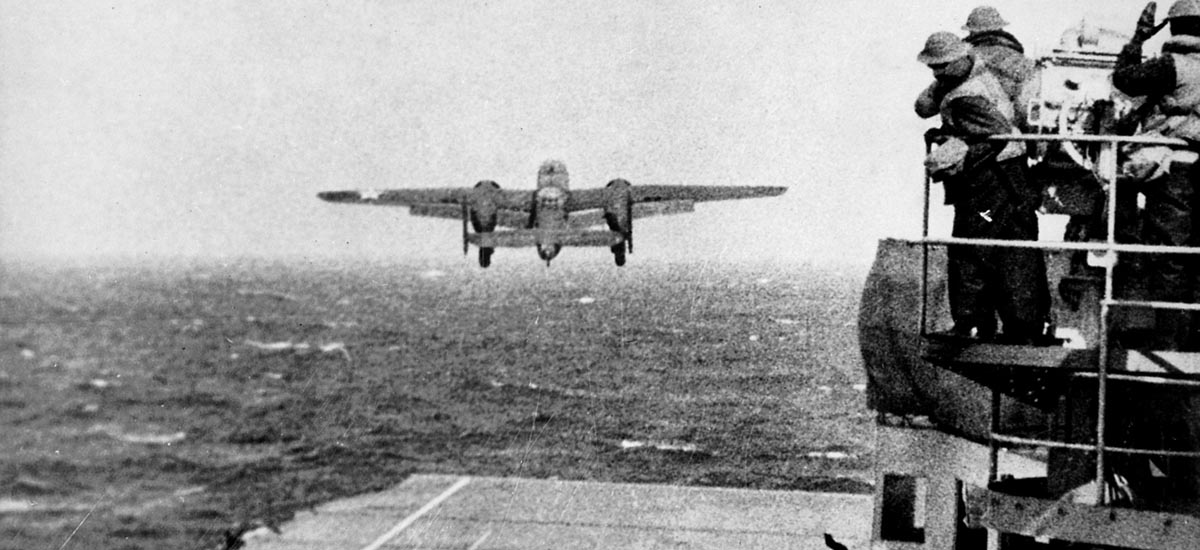

Little more than four months after the disastrous attack on Pearl Harbor, America went on the offensive against Japan with one of the boldest and best remembered bomber raids of World War II. Led by Lt. Col. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle and laden with extra fuel, 500-pound bombs, and incendiary clusters, 16 North American B-25 Mitchell bombers lumbered 500 feet along the wooden flight deck of the 19,900-ton Yorktown-class aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) early on Saturday, April 18, 1942, and took off into a stiff wind. They climbed into a rainy, murky sky and flew 800 miles eastward to hit military targets in the Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, and Yokohama areas.

It was the first and only time that bombers had been launched from a carrier, and they achieved complete surprise when they reached their objectives. The material damage they inflicted was slight, but the raid had a major psychological impact. The stunned Japanese were forced to push forward their planned attack on Midway Atoll, preventing further carrier attacks against their country, while the Americans received a much needed morale lift after a series of defeats in the Far East.

The gallant Doolittle was awarded the Medal of Honor, and his historic raid—the country’s first victory of the war—gained instant fame for the North American B-25 Mitchell, one of the most widely used and effective twin-engine bombers of the war. Meanwhile, the chunky, affable Doolittle, a record-breaking peacetime air racer, became a national hero and went on to command successively the U.S. Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces, the Northwest African Strategic Air Force, and the Eighth Air Force. (Read all about the exploits of the Mighty Eighth inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

The B-25 “Mitchell” Bomber: Origin of the Name

Named for Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, the charismatic airpower prophet who proved in 1921 and 1923 that planes could sink battleships, the B-25 Mitchell gained an unsurpassed reputation as a ground-attack bomber and ship killer. The rugged, versatile B-25 saw action on almost every Allied front, from the Mediterranean to the Pacific, and from Burma to Normandy, and was regarded by many as the most successful twin-engine combat aircraft of World War II.

The plane was conceived before the outbreak of the 1939-1945 war. In response to an Army Air Corps proposal for a twin-engine attack bomber, North American Aviation, Inc., produced a prototype designated NA-40-1. The moving force behind the design was the company’s brilliant president and chief designer, James H. “Dutch” Kindelberger, a West Virginia-born World War I aviator. He was also responsible for the legendary P-51 Mustang fighter, arguably the best fighter plane of the conflict.

Powered by two 1,100-horsepower Pratt & Whitney engines, the forerunner of the B-25 Mitchell bomber, had a shoulder-wing design, a tricycle landing gear, and was capable of carrying a 1,200-pound bomb load. Its armament consisted of .30-caliber machine guns in the nose, dorsal, and ventral positions. Built at the company’s Inglewood, California, plant, the prototype was first flown by test pilot Paul Balfour in January 1939. The engines were soon replaced by 1,300-horsepower Wright Cyclones, the plane was redesignated NA-42, and it was delivered to Wright Field in Ohio in March 1939 for USAAC evaluation.

Although the prototype crashed two weeks later because of pilot error, the Air Corps was impressed with the NA-42 design, although some changes were requested, including an increase in the bomb load and armament. North American was engaged to continue development under the basic design, NA-62, and this was completed in September 1939, when war broke out in Europe. An immediate contract called for 184 bombers, now designated B-25.

Several improvements were made. The wing was relocated to a mid-position, operating weights and the bomb load were increased, a tail gun position was added, and the engines were upgraded to 1,700-horsepower Wright Cyclone radials. Self-sealing fuel tanks and crew protection armor plating were added later. Stability problems were solved by giving the plane a gull wing.

Building a B-25

Building a B-25 Mitchell was a complex and lengthy matter. Half the size of a Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bomber, it contained 165,000 separate items, not counting the 150,000 rivets that held it together. By 1944, the average cost of the Mitchell was $142,194, or $50,000 less than its successor, the Martin B-26 Marauder.

The B-25, which continued to undergo many further improvements, had a crew of four to six men, weighed 35,000 pounds, was 53 feet long, had a wingspan of 68 feet, and carried a 3,000-pound bomb load. Its top speed was 272 miles per hour at 13,000 feet, its service ceiling 24,200 feet, and its range 1,350 miles.

The U.S. Army Air Forces accepted a total of 9,816 B-25s produced at North American’s Inglewood and Kansas City, Kansas, plants, but it never had more than 2,700 on hand at any one time during World War II because of the numbers supplied to other American and Allied air units.

The first production model of the B-25 Mitchell bomber was test flown on August 19, 1940, and 40 further improved B-25As were built. This was the first Mitchell variant to see operational service, with the 17th Medium Bombardment Group based at McChord Field, Washington. The planes flew antisubmarine patrols, and their first kill was notched on Christmas Eve, 1941, when a Japanese submarine was sunk off Puget Sound on the U.S. West Coast.

B-25s in Action

More Mitchells went into action in 1942 and soon proved their worth with American and Allied air units. B-25V variants were among U.S. reinforcements sent to Australia, where they served with the 13th and 19th Squadrons of the 3rd Bombardment Group, and others were pressed into service with the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Dutch, Brazil, the Soviet Air Force, China, and the British Royal Air Force.

The advent of the B-25 enabled the hard-pressed RAF to replace the Bristol Blenheims, Douglas A-20 Bostons, and Lockheed Venturas flown by its No. 2 Group on daylight operations over northwestern Europe. Although Mitchells were not assigned to the U.S. Eighth Air Force in England, 712 of them were earmarked for seven RAF squadrons. The RAF crews loved the sturdy, reliable B-25 as much as their American counterparts.

As the Allies went on the offensive in 1942 and 1943, increasing numbers of Mitchells fought in almost every combat theater, manned by American, British, Australian, Canadian, Dutch, Chinese, Polish, and Soviet crews. They bombed and strafed ground targets, blasted enemy shipping, supported amphibious invasions, and were also used as trainers, transports, and photoreconnaissance planes.

Wherever it was deployed, the maneuverable B-25 was one of the deadliest and most effective weapons in the Allied aerial arsenal. Carrying 3,000 pounds of bombs or eight five-inch rockets and bristling with a dozen .50-caliber machine guns, it proved to be virtually indispensable. Because of its firepower, it did not require fighter escort.

As the war progressed, the B-25 underwent many modifications, chiefly in its armament. Cannons and glide torpedoes were mounted, and some were even equipped with 75mm field guns. The gun proved effective in dealing with ground targets and enemy submarines, but was eventually replaced by machine guns. In the end, Mitchells carried almost every combination of guns and bombs that their pilots and crews could imagine.

In the China-Burma-India Theater, the USAAF’s 341st Bomb Group found that the B-25s were so rugged that they could operate from makeshift dirt and grass airstrips, range far behind Japanese lines, and strike supply dumps at low level. In the Pacific Theater, Mitchells of the 345th Bomb Group operated at relatively long range, attacked Japanese ships at wave-cap altitude, and survived direct hits from small arms fire.

Workhorse Medium Bombers: Devastating Daylight Attacks Against German and Italian Installations

Clad in yellowish desert camouflage, meanwhile, B-25s were widely used in the Mediterranean Theater. In July 1942, Mitchells of the U.S. 12th Bombardment Group joined Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton’s Middle East Air Force (later Ninth Air Force) at Fayid in northern Egypt. B-25s supported British Eighth Army forces at Alam Halfa and in the great Battle of El Alamein on October 23, 1942, the first major Allied victory of the war, and helped to clear the skies for Operation Torch, the three-pronged invasion of North Africa, the following November.

The workhorse medium bombers then bombed and strafed in some of their heaviest fighting of the war. While RAF Vickers Wellington bombers kept up the pressure at night and A-20s mounted their famous “Boston Tea Parties,” the British and American Mitchells carried out devastating daylight attacks on German and Italian troop concentrations, convoys, panzer columns, airfields, bridges, marshaling yards, and the port areas of Sfax, Sousse, Tunis, La Goulette, and Bizerte. The Allied air groups in North Africa gained almost absolute supremacy over the Luftwaffe.

Once the Allies had vanquished the German Afrika Korps and its Italian allies in May 1943 and the Mediterranean war shifted to Sicily and Italy, Mitchells joined the action from bases in Sardinia and Corsica. A bombardier in one of the USAAF B-25 groups, Joseph Heller, related his experiences in a satirical novel, Catch-22. The best-seller was published in 1955.

Before and after the invasion of mainland Italy by the British Eighth and U.S. Fifth Armies, Allied B-25 Mitchell squadrons flew numerous sorties to soften up stubborn German opposition. On August 13, 1943, 66 Mitchells joined a force of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-26s, and Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters in an assault on major marshaling yards in Rome. They stopped through traffic to Naples for five days.

A few months later, after many more combat missions, 77 Mitchells were again in action when a large force of Allied bombers blasted the enemy-held monastery at Monte Cassino, site of some of the most intense action on the Italian front, on March 15, 1944. Seventy-seven B-25s, 164 B-24s, 114 B-17s, and 105 B-26s dropped their bombs, followed by an eight-hour artillery barrage. The assault was unprecedented in the Mediterranean campaign. Half the defenders of the German 1st Parachute Division were killed or wounded, but the rest held their ground and sent heavy fire against advancing Allied infantry.

On May 11, 1944, B-25s of the U.S. Twelfth Air Force began Operation Strangle in central Italy, bombing and strafing enemy supply routes along the lengthy, formidable Gustav Line. The aerial offensive culminated in the triumphal liberation of Rome by the Fifth and Eighth Armies on the following July 4.

As on other fronts, the Mitchells were giving sterling service as strafers, bombers, and skip bombers while the Allied naval and ground offensive intensified in the Pacific. In the great Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943, B-25s equipped with 10 forward-firing machine guns and 500-pound bombs played a key role by almost annihilating a Japanese convoy without loss to themselves.

The Sweetheart of the Services

The U.S. Navy purchased 706 Mitchells (PBJs) based on Army models, but, except for a handful used for developmental work, these were transferred to the Marine Corps for deployment in the Pacific Theater. The Marine Corps had 16 B-25 squadrons, nine of which flew in combat, starting at Stirling Island in March 1944. The PBJs were used effectively in subsequent operations, including the invasions of Saipan in June 1944 and Iwo Jima in February 1945. The Marines lost 26 B-25s in action and another 19 in noncombat mishaps.

Nicknamed “Billy’s Bomber” and “The Sweetheart of the Services,” its pilots and crews loved the Mitchell because of its ability to wreak havoc on enemy targets and still survive. “It is amazing how much punishment the B-25s could take,” said Lieutenant David Hayward, a pilot with the 341st Bomb Group based in India and the Pacific. “There were relatively few vulnerable places on the airplane. We had armor plate under our seats. The gasoline tanks were self-sealing. What we sacrificed in speed we gained in security.”

The maneuverable and well-armored planes were praised by all crewmen except the occupants of their cramped belly-gun turrets. On his knees, the gunner had to sight through a periscope of lenses and mirrors while using a dual hand control. The disjointed mechanism made most operators too dizzy to fire. “The bottom turret was very complicated and worked backwards to what was normal,” reported one mission commander. “It would have taken more time than we had available to master it. A man could learn to play the violin good enough for Carnegie Hall before he could learn to fire this thing.”

Otherwise, and despite its flaws, the Mitchell received high marks from its pilots and crews. “The B-25 was a really superior airplane, right on the cutting edge of technology for medium bombardment,” said 24-year-old Lieutenant Travis Hoover of Melrose, New Mexico, commander of the second plane in the Doolittle Raid. “We kind of fell in love with it.”

Lieutenant Ted W. Lawson of Fresno, California, also 24 and commander of the Ruptured Duck, the seventh plane in the group, agreed, “You just had to stand there and look at them, and breathe heavily. It’s a grand ship—fast, hard-hitting, and full of fight. It is so much more than an inanimate mass of material, intricately geared and wired and riveted into a tight package. It is a good, trustworthy friend.”

Lawson, who had to have one of his legs amputated after the famous raid, published the best-selling memoir Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,in 1943.

Bombers in the Movies

Inevitably, Lawson’s book was viewed by Hollywood as a hot property and national morale booster. Although Colonel Doolittle was unwilling to have a film portraying him produced until the war ended, work got underway at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. The book was translated for the screen by writer Dalton Trumbo, working closely with producer Sam Zimbalist and director Mervyn LeRoy, and filming continued through 1943 and 1944. Resources were limited, but the Army Air Forces nevertheless loaned MGM a dozen B-25s and crews. For a wartime production, it was a remarkable job. The Hornetflight deck had to be recreated on a Hollywood sound stage, and an oil refinery fire in East Oakland, California, stood in for the bombing of Tokyo, but many scenes were shot on location at Eglin Field, near Pensacola, Florida, where the Doolittle Raiders had trained for a month.

Spencer Tracy portrayed Doolittle, Van Johnson played Lawson in his breakout role, and the supporting cast included Phyllis Thaxter, Robert Walker, and Robert Mitchum. The film premiered in Glendale, California, in September 1944. Taut and realistic, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyowon an Academy Award for special effects, a nomination for photography, and became an MGM hit and a long-running favorite with audiences. It was one of the best Hollywood service films to appear during the war years.

When the Allied aerial offensive increased in the European Theater, meanwhile, American medium bomber groups were equipped with the B-26 Marauder and A-20 Havoc because of concern about the Mitchell’s ability to stand up to intense German antiaircraft fire. B-25s nevertheless saw plenty of action, starting with a raid on January 22, 1943, when a dozen planes from the RAF’s No. 98 and 180 Squadrons attacked an oil refinery at Ghent, Belgium.

Along with Havocs, Marauders, De Havilland Mosquito fighter bombers, and rocket-firing Hawker Typhoons, the Mitchells flew many low-level missions against enemy transports, communications, and radar centers in France, softening up German defenses before and during the momentous Allied invasion on June 6, 1944. Air Vice Marshal Sir Basil E. Embry, commander of the RAF’s 2nd Tactical Air Force’s No. 2 Group, reported, “On the morning of D-Day itself, our Mitchell squadrons attacked with great accuracy gun positions directly threatening the approach of the great armada to the Normandy beachhead, and our Bostons (A-20s) flying at sea level laid the smoke screen over the invasion craft.”

The powerful 2nd Tactical Air Force, which comprised all of the RAF Mitchell squadrons based in England, employed the B-25 Mitchell bomber in sub-formations of five planes on its daylight operations. In this way, the tremendous firepower of 13 .50-caliber machine guns provided formidable defensive cover. Another practice was to use Mitchells and Mosquitoes together on night raids, with the former acting as target illuminators.

The Mitchells went on to support British and Canadian forces in their costly, month-long struggle to capture the strategic city of Caen in the fiercest action of the Normandy campaign. Besides scourging German troop concentrations, tank formations, supply dumps, rail lines, and bridges, the planes blasted German V-1 and V-2 rocket sites. Almost daily, they served valiantly in their close tactical role as the British, U.S., and Canadian Armies battled eastward toward the River Rhine and into Germany. The last operation of the European War for B-25s was mounted on May 2, 1945, when 47 planes of the RAF’s No. 2 Group blasted marshaling yards at Itzhoe in Schleswig-Holstein.

The B-25 Mitchell that Crashed into the Empire State Building

The workhorse medium bombers remained in action almost until the end of the Pacific War in the summer of 1945, while one of them made headlines much closer to home.

Early on the morning of Saturday, July 28, 1945, Lt. Col. William F. Smith of Bedford, Massachusetts, took off in his B-25 and headed south toward Newark, New Jersey. He was accompanied by his copilot and a young sailor hitching a ride home to New Jersey. The control tower at New York’s LaGuardia Field warned Smith of extremely poor visibility in the metropolitan region, and he became disoriented in cloud and fog. At 9:40 am, the bomber slammed into the world’s tallest building, the Empire State Building, in midtown Manhattan, gouging an 18-by-20-foot hole between the 78th and 79th floors.

Part of the fuselage lodged itself in the skyscraper’s north façade, one engine tore through seven walls, and the other crashed into the elevator shaft. The building “shuddered, realigned itself, and settled,” according to historian John Tauranac. There was an explosion, and high-octane fuel spewed from the Mitchell’s ruptured tanks and sprayed the building. A wing section fell on Madison Avenue, and other parts of the plane rained on a five-block area.

Despite the severe damage, only 10 people died besides the three men in the plane, and 25 were injured. If it had not occurred early on a Saturday morning, the disaster would have been much worse. On a normal business day, about 15,000 workers and 35,000 visitors might have been in the building. The female operator of the elevator survived miraculously when cables were severed and her car plummeted 80 floors into the building’s sub-basement.

Deliveries of Mitchells stopped in August 1945, but after the Allied victory, many of the planes continued in use. The U.S. Air Force converted several hundred into pilot trainers, while others were stripped down to become transports. Besides Canada and Australia and several smaller air forces, postwar users of B-25s included the Soviet Union, Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Dominica, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Indonesia. Mitchells supplied to the Chinese Air Force remained in service throughout the postwar struggle that led to the communist overthrow of Chiang Kai-shek’s government.