By Mason B. Webb

In the weeks leading up to the still-undefined D-Day, commanders argued about every detail of Operation Overlord. Sometimes, the arguments grew contentious. In one, just a few weeks before the Normandy invasion was launched, British Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, under whose aegis the airborne forces would operate, got cold feet and told Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. 1st Army, which was slated to land at Utah and Omaha Beaches, that he feared casualties among the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions would be catastrophic and urged the commander of Overlord ground forces, General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, to cancel them.

Furious, Bradley replied that if the airborne and glider landings were eliminated, then he would insist that the whole Utah Beach plan be scrapped. “I won’t go in without the airborne,” Bradley told Leigh-Mallory. Ultimately, Monty had to step in and settle the heated disagreement, ruling that the airborne and glider portion of the invasion would proceed as planned.

Leigh-Mallory’s pessimism and predictions of doom were one more burden for Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower to carry. Ike noted in Crusade in Europe, “If [Leigh-Mallory] was right, it appeared that the attack on Utah Beach was probably hopeless, and this meant that the whole operation suddenly acquired a degree of risk, even foolhardiness, that presaged a gigantic failure, possibly Allied defeat in Europe.”

The airborne and seaborne landings at Utah Beach had been deemed vital, because in addition to being a blocking force that could prevent the Germans in the Cotentin Peninsula from attacking the western end of the invasion area, the troops that landed at Utah would be in good position to head north and, it was hoped, capture the deep-water port at Cherbourg.

In the event, Ike did not order the Utah assault cancelled. “To abandon it,” he said, “really meant to abandon a plan in which I had held implicit confidence for more than two years.”

Nevertheless, as Eisenhower biographer Michael Korda wrote, “Nobody liked the look of Utah Beach, the only one that was available [on the east coast of the Cotentin Peninsula]. Ike himself described it as ‘miserable.’ On the landward side was a shallow, wide lagoon, crossed by narrow causeways, on which the Germans would certainly direct their artillery. If the Germans could hold on to the exits from these causeways, the troops would be trapped on the beach and ‘slaughtered’ there.”

SHAEF had the responsibility of selecting the units that would participate in Overlord, and the planners were worried that two of the three American infantry divisions slated to land by sea (the 4th and 29th) had not seen combat before, but it could not be helped. The only other experienced combat divisions on that side of the world were tied down in Italy. Selected to lead the charge at Utah Beach, therefore, was the U.S. 4th Infantry Division.

How the 4th Infantry Division Became Known as the “Ivy Division”

The 4th’s lineage began in December 1917 when it was formed as America geared up to take part in World War I. In April 1918, the “Ivy Division” embarked for France. (The nickname comes from the design of the division’s insignia, which has four green ivy leaves joined at the stem. The word “Ivy” is a play on the Roman numeral four, or IV. Ivy leaves are symbolic of tenacity and fidelity, the basis of the division’s motto, “Steadfast and Loyal.”)

It fought with distinction in the Marne and Aisne regions, and was the only American combat force to serve with both the French and the British in their respective sectors, as well as with all corps in the American sector.

When the Great War ended on November 11, 1918, the Ivy Division was awarded five battle streamers. More than 2,000 officers and men had been killed in action, and the list of wounded and missing totaled 12,000.

Deactivated at the conclusion of “the war to end all wars,” the 4th was brought back to life a month after Nazi Germany invaded France, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

Reactivated on June 1, 1940, at Fort Benning, Georgia, the division was made up of the 8th, 12th, and 22nd Infantry Regiments, plus supporting units. From August 1940 through August 1943, the division was designated a “motorized” division and participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers, then moved to the newly opened Camp Gordon, Georgia, where it took part in the Carolina Maneuvers.

“Tubby” Barton: Commander of 4th Infantry

On July 3, 1942, 53-year-old Maj. Gen. Raymond Oscar “Tubby” Barton was appointed commander of the 4th Infantry Division, coming into the position with a reputation as an exacting and demanding leader.

Barton was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1890 and graduated from West Point in 1912. Although his sports at West Point were boxing and wrestling, he somehow acquired the nickname “Tubby,” a moniker that stayed with him the rest of his life. He served in World War I in France with the 1st Battalion of the 8th Infantry Regiment.

One 4th Division colonel later described Barton as “a very strict disciplinarian who commanded his division with an iron hand.”

His no-nonsense attitude was made clear when he first addressed the officers and men of the 4th Division on the day he assumed command: “I am your leader…. In the not-too-distant future, we will be in battle. When bullets start flying, your minds will freeze, and you will act according to habit. In order that you develop the right habits, training discipline must be strict. I know that 90 percent of you want to cooperate. I will take care of the other 10 percent.”

A member of the 22nd Regiment said, “His manner was firm and brisk, but not sour or stiff. The rank and file are strongly impressed with the ability and energetic leadership he has exhibited in the short time since he took command of this division.” It would be his leadership and his instilling of discipline in his young, untried soldiers that would be a major factor behind the division’s success in the battles to come.

The 4th finally moved to Fort Dix, New Jersey, and was converted back to a “regular” infantry division redesignated the 4th Infantry Division. In September 1943, the 4th moved again, this time to Camp Gordon Johnston, Florida, where the men received realistic amphibious training in preparation for the assault on Fortress Europe.

In early 1944, the division was sent to England to prepare for the long-awaited invasion of Europe. The division was spread out in camps across Devon in towns with names such as Newton Abbot, Tiverton, and Bishopsteignton.

Before the division set foot on French shores, though, it would require a further tuning-up prior to D-Day.

Fighting Mock D-Day Battles in Britain

It had been decided that the units going into Normandy on D-Day needed to rehearse their actions in places in the UK that most resembled the actual landing places in France. For that reason, the beach at Slapton Sands in Lyme Bay on the Devon coast was found to be an almost identical twin to the place where the troops destined for Utah Beach were scheduled to land.

In December 1943, homes, businesses, and villages in the South Hams area of Devon were ordered abandoned by the British government so that the soldiers could gain experience fighting mock battles in real towns. More than 3,000 people found themselves uprooted by government order.

In April 1944, to prepare the green troops for the real thing, it was decided to use live ammunition during a full-scale dress rehearsal known as Exercise Tiger. Perhaps things were a bit too realistic. A stray dog ran into the lobby of the abandoned Slapton Sands Hotel, triggering a demolition device that destroyed the building—and the dog.

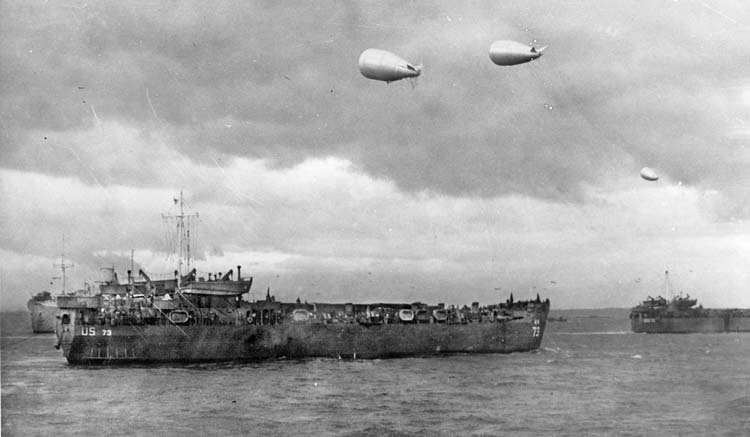

During Exercise Tiger, a number of LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) were being protected by two British Royal Navy destroyers, three torpedo boats, and two motor gunboats bristling with .303 Vickers machine guns, depth charges, and 6-pound cannons. Their role was to guard Lyme Bay and keep away any enemy who might want to interfere. But a mix-up led to tragedy.

On April 22, according to historian Robert Heege, “Unaware that both the live-fire battle simulation and H-hour had been delayed, several LSTs, still adhering to the exercise’s initial timetable, made landfall and disembarked their men at Slapton Sands just as the now-rescheduled naval bombardment began raining shells down on the beach.

“Soldiers that had never really expected to be placed in harm’s way in what was supposed to be a simulation, albeit an ultra-realistic one, suddenly found themselves in danger of being blasted to pieces. According to plan, the machine guns firing just above their heads had also been directed to fire a few bursts into the ground a few yards ahead of the landing zone on U Beach for the added benefit of the infantrymen as they came ashore, a realistic touch that was to have chilling consequences.

“As the machine gunners’ bullets began tearing up the gravel directly in front of them, the now understandably bewildered soldiers reacted like a clutch of startled bumblebees. Worse still, the soldiers hitting the beach had been ordered to return fire at their imaginary enemy as they went forward as part of the simulation. Many did so, apparently under the impression that they had all been issued blank cartridges. However, the GIs on the beach that day had inadvertently loaded up their rifles with real ammunition instead of blanks. Bunched up as they were, some of the boys became the unwitting casualties of friendly fire.

“Meanwhile, according to plan, the British heavy cruiser HMS Hawkins continued its bombardment, pouring ordnance into a designated section of the beach that the beach wardens had obligingly marked off for the naval gunners with a cordon of white tape. In the ensuing chaos and confusion, scores of soldiers desperately attempting to get out of the line of machine-gun fire strayed across the white demarcation line and ended up directly in the kill zone. As the officers on the bridge of the Hawkins looked on in stunned horror and disbelief, these unfortunate souls were practically vaporized, blown to bits by the Royal Navy’s big guns.”

As if that weren’t bad enough, soldiers participating in a night exercise five days later encountered an even greater tragedy. As eight LSTs loaded with 4th Division troops made their run into shore, a squadron of German torpedo boats (known as E-boats, the equivalent of the U.S. Navy’s PT boats) appeared out of nowhere and began attacking the unsuspecting flotilla.

A British journalist noted, “At first, many of the Americans thought that it was all part of the realism of the exercise. Then there were explosions and huge mushrooms of fire as the torpedoes struck. In that one terrible night, more than 800 U.S. servicemen died. And they were only practicing.” It would be a toll far greater than what the division would suffer on D-Day.

Complete secrecy was clamped around the disaster. For decades, it was hushed up. Army surgeons and nurses were threatened with court-martial if they even spoke with the wounded, and the casualty lists were kept top secret. Families were only notified that their loved ones had died due to a training accident.

Despite the tragedy, Operation Overlord would go on as scheduled.

4th Infantry Division Becomes “Force U”—with Utah Beach as Their Destination

After being delayed for 24 hours because of a strong storm sweeping through the English Channel, the great day arrived, and with it, a great armada that had been assembled for Operation Neptune—the assault phase of Overlord—in the hours before dawn: more than 4,000 landing craft; 287 minesweepers; 138 destroyers, cruisers, and battleships; 221 escort destroyers; 1,260 merchant ships; and more than 400 ancillary ships.

Packed into their transports were 156,000 young American, British, Canadian, and Free French troops. Thousands of American and British sailors and Coast Guardsmen stood ready to play their part in this biggest of war dramas, history’s largest and most important combined air and sea invasion.

The 4th Infantry Division, scheduled to sail from Plymouth, England, and land at Utah Beach, had been designated “Force U.” (Troops destined for Omaha Beach were “Force O.”) Once the beachhead had been secured, follow-on forces would arrive at Utah later in the day. These included the 90th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Jay W. MacKelvie) and the 4th Cavalry Regiment (Colonel Joseph Tully).

To soften up German defensive positions, 18 ships from the U.S. Navy (including the battleship USS Nevada, sunk at Pearl Harbor but repaired in time for Overlord) and Royal Navy pummeled miles of shoreline with thousands of high-caliber shells.

Then, 20 minutes before the scheduled 6:30 am seaborne landings began, 300 Martin B-26 Marauders of the U.S. Army Air Force’s IX Bomber Command came in low over the beachhead and laid their ordnance effectively on German positions. (This was in stark contrast to what happened at Omaha Beach, where the Navy overshot its targets and the air force bombed too far inland.)

A heavy shroud of smoke and dust from the bombing and naval gunfire hung over the beachhead, obscuring the view of German gunners. Onboard one of the rocket-firing boats off Utah Beach was 19-year-old Seaman Second Class Lawrence P. “Yogi” Berra, a future New York Yankees baseball player who had enlisted in the Navy. “It was just like a Fourth of July celebration,” he remarked about the fiery barrage.

He said in an interview 65 years after the war that he was proud of the small part he played in the D-Day invasion. “I felt sorry for the paratroopers who went in there before us. They caught hell over there, boy.”

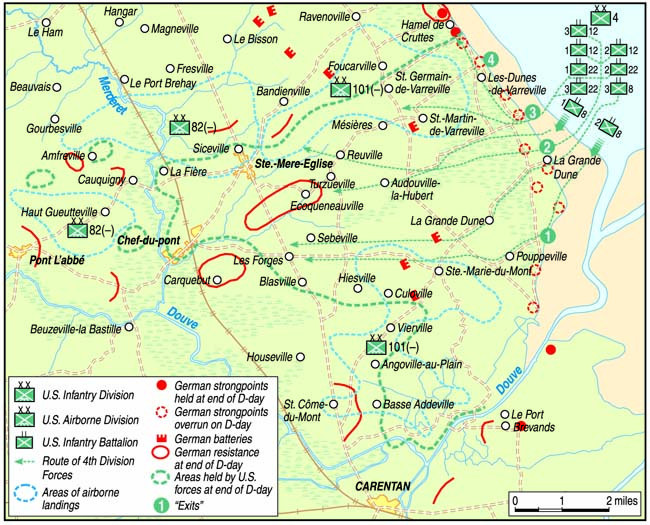

Two American airborne divisions, the 82nd and 101st, had dropped into Normandy a few minutes after midnight on June 6. Their casualties, as Leigh-Mallory had feared, were heavy, but they managed to sow confusion among the enemy, stop German reinforcements from reaching the beachhead, and captured important towns and road junctions.

The Story Behind Teddy Roosevelt Jr.’s Famous Landing at Utah

At 6:30 am, 300 men of Lt. Col. Carlton O. MacNeely’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment of the 4th Division became the first Allied seaborne unit to hit the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Their group of 20 LCVPs landed at low tide at Les Dunes de Varreville near the hamlet of La Madeleine. After wading in waist-deep water for 200 yards, the men threw themselves down on the golden sand, waiting for German rifles or machine guns to open up on them.

Surprisingly, the only noise of battle to greet them was the crump of random mortars and artillery shells and the ripping sounds of shells still flying overhead from Allied ships off shore. The expected fury of enemy fire just didn’t happen.

The landing area was divided into three sectors: Tare Green, Uncle Red, and Victor. Landing at Tare Green were Companies B and C, while Companies E and F landed to their left on Uncle Red. Captain Leonard T. Schroeder, commanding Company F, is credited with being the first American to reach Utah Beach. He later told an interviewer, “Today, I realize that to be the first man ashore is an immense honor, yet I do not merit it more than anyone else. Five of my men died at Normandy. They alone are the heroes.”

Wading ashore with the first wave was a little man with a cane who wore a single star on his steel helmet. His name was Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the eldest son of the former “Rough Rider” president of the United States and the fifth cousin to the current occupant of the White House.

It quickly became apparent to Roosevelt and other officers in the first wave that they had landed at the wrong beach. They had come ashore not north of the Madeleine as planned but to the south of that village, under the gun embrasure of the German strongpoint WN5. The strong current had pulled them too far to the southeast, and three of the four designated control craft that were supposed to have guided the Higgins boats in had been lost to mines.

The sole surviving control craft eventually rounded up the confused LCVP drivers who were still looking for landmarks they had memorized, and using a bullhorn for communication, led them in. The force eventually landed one mile southeast of its designated landing area, in the less heavily defended Victor sector at Exit 2.

While under fire, Roosevelt gathered the 8th Regiment’s Colonel James Van Fleet, Commodore James Arnold, the naval officer in charge of the Utah Beach landings, and other officers to make a command decision. Realizing they were in the wrong place, Roosevelt said in his bullfrog voice to Arnold, “I’m going ahead with the troops. Get word to the Navy and bring them in. We’ll start the war from here.” He designated the new landing beach as “Uncle Red.”

Allied Tanks Hit the Sands at Normandy

Officers began shouting, “Get going! Get off the beach!” and small clumps of men began moving forward, running through the soft sand and crawling over the low dunes covered with tall beach grass, hoping to avoid the profusion of mines that seemed to be everywhere.

One of the 8th Infantry soldiers, Harry Bailey of Company E, remembered jumping off the ramp of his landing craft into waist-deep water. He recalled that a man in his platoon “was the first to reach the sand dunes, and I ran and dropped down beside him…. He was immediately killed with a hit to the head by a sniper’s bullet. I knew I had to move fast or I would be next.”

German shells now began exploding here and there on the beach, throwing up huge geysers of sand and water. But the shelling seemed to have no intensity to it. Swinging to the right toward La Madeleine, the men of Van Fleet’s 8th Infantry Regiment saw a group of concrete German pillboxes and casemates scattered across open fields that had been flooded, and waded toward them, killing or capturing their occupants.

Five minutes after the first wave hit the sands, the second wave—Companies A and D of the 1st Battalion and Companies G and H of the 3rd Battalion—began arriving at Tare Green to the north of Uncle Red. Accompanying them were combat engineers and underwater demolition teams who set to work removing and destroying beach obstacles and mines.

Next came the amphibious tanks. A group of 32 duplex-drive (DD) Sherman tanks from the 70th Tank Battalion was supposed to have arrived 10 minutes before the infantry, but rough sea conditions caused them to be 20 minutes late.

Four swimming Shermans of Company A never made it at all because their LCT (Landing Craft, Tank) struck a mine and sank. The remaining 28 tanks made it safely to the beach. They began pulling themselves out of the sea, their long-barreled snouts looking for something to shoot at.

Sam Grundfest was a junior officer on the LCT that lost the four tanks. “It blew us sky-high,” he recalled. “The other officer in the boat was killed. Everyone was killed except me and two of the Navy personnel…. And the four tanks were lost. I didn’t hear the explosion that blew up my boat, but when I opened my eyes, I was underwater…. Were it not for the Mae West life jackets that we wore … I don’t think I would be here today.”

Shortly thereafter, the next armored wave arrived: 16 conventional Sherman tanks and eight tanks outfitted with bulldozer blades delivered by LCTs.

British sailor Graham Hiscox, aboard an LCT of the Royal Navy’s 44th LCT Flotilla, was helping to offload the Shermans. His craft was soon targeted by German shore batteries, but the Allied fleet gave them covering fire, which stopped the German guns—the crews of which now feared giving away their position—from firing.

It was only some time later that Hiscox learned where they had landed. “My job was simply to look after the craft’s engines and generators,” he said, “So I wasn’t party to any information where we were heading.”

The 4th’s Remarkable Job Ashore

The 4th Division had planned to have artillery support on D-Day, but a large landing craft carrying 60 men of Battery B, 29th Field Artillery Battalion struck a mine and all 60 were killed.

At about 10 am, elements of Colonel Hervey A. Tribolet’s 22nd Infantry Regiment began arriving. As enemy defenses succumbed to the Americans, the 22nd pushed northward along the coastal road and through the flooded fields toward St. Germain de Varreville, terrain that was occupied by the German 709th Infantry Regiment.

The 3rd Battalion of the 22nd Infantry, supported by five tanks, moved north along the shoreline to eliminate German strongpoints as they were encountered. In some cases, naval gunfire had to be called in to finish the job.

Morris Austein, Company I, 22nd Infantry, recalled, “On the shoreline itself, there were land mines. Germans put them down, and if you stepped on one, you blew up. I lost five men that way. There was utter confusion on the beach, and soldiers were crying for help.”

Meanwhile, 8th Regiment infantrymen were pushing farther inland, engaging any Germans who might have survived the naval and air bombardments. As they advanced upon defensive position WN7 and the headquarters of 3rd Battalion, 919th Grenadiers near La Madeleine, which was 600 yards inland, the men of Company B met little resistance. At the same time, Company C attacked the enemy strongpoint WN5 at La Grande Dune, which essentially had been knocked out by the bombardment.

Companies E and F advanced inland about 700 yards to defensive position WN4 at La Dune, where they encountered some stunned Germans who put up a brief fight before being eliminated. As this action was taking place, Companies G and H moved south along the beach to Beau Guillot and enemy strongpoint WN3. There they encountered a minefield and came under machine-gun fire but soon captured the position.

For soldiers who had never before seen combat, the men of the 4th Infantry Division were doing a remarkable job.

Land Mines in their Midst

Arriving in a later wave, 25-year-old infantryman Claire Galdonik was heading shoreward in an LCVP, watching naval shells exploding inland and dirty black clouds roiling in the sky. The boat scraped the sand, the ramp dropped, and suddenly Galdonik was in the water with the other men who had been penned up in the landing craft. They trudged toward land.

“Something I feared more than German artillery was … stepping on a land mine,” he confessed. “So far, so good, but enemy shelling had taken its toll on the beach area. Tanks and trucks were gutted and burning, but only a few dead Americans were there. It shook me up.”

Captain John L. Ahearn, Company C, 70th Tank Battalion, recalled that his tank company was the first armored unit landed on the beach. Once ashore, he took a group of seven Shermans south toward Pouppeville.

“As my tank proceeded down a small lane, it hit a land mine. The front left bogie wheel was blown off, and we were immobilized.” Ahearn climbed out of his tank and heard cries for help. He went across several hedgerows before he found several wounded paratroopers. He went back to his tank to retrieve a medical kit, but while returning to the injured men, stepped on a mine that knocked him unconscious. He was taken back to a field hospital.

“I later learned from our battalion maintenance officer that they had discovered some 15,000 mines in that vicinity. So the odds were not very good that I would be unharmed.”

Ahearn’s war was finished; surgeons had to amputate one of his mangled feet.

The Germans Push Back at Ste. Marie-du-Mont and Fauville

Lieutenant Colonel Carlton O. MacNeely’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, accompanied by several Shermans, pushed inland along Causeway 1 toward Pouppeville, only to discover that the hamlet was already in the hands of the 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment. There was understandable joy when the two battalions met up.

As more men and tanks piled onto the sand, Causeway 2, directly behind La Grande Dune (today the site of the Utah Beach museum at the former WN5), soon became the main exit road off the beach in the direction of Ste. Marie-du-Mont, about three miles inland.

In his book, Utah Beach, author Joseph Balkoski said that the Germans had blown a small bridge over a culvert, and movement was delayed while engineers made repairs. With Causeway 2 becoming congested, some units waded through the flooded areas beside the road.

The 6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment of the German 91st Infantry Division was prepared to defend Ste. Marie-du-Mont, but members of the 506th Parachute Infantry, 101st Airborne Division successfully attacked and knocked out the batteries at Holdy and Brécourt Manor, then took Ste. Marie-du-Mont in house-to-house and street combat, allowing Lt. Col. Erasmus H. Strickland’s 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry to advance up Causeway 2 practically unopposed.

By mid-afternoon on D-Day, Strickland’s men, accompanied by elements of the 82nd Airborne, reached National Highway 13 at Les Forges and then headed north to Fauville (less than half a mile southeast of Ste. Mère-Église), where a group of Germans were holding out. Although encircled to the north by the parachutists and to the south by the 3rd Battalion (supported by tanks), the Germans held firm at Fauville and prevented any advance along the national road.

1,700 Vehicles and 23,250 Soldiers Ashore on Utah Beach

Time was of the essence: the Americans needed to neutralize this position that threatened the later arrival of glider reinforcements on nearby Landing Zone W, which was still within range of the Germans.

The 4th Division’s 12th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Russell P. Reeder, Jr., was now ashore and, without any opposition to hold the regiment back, began moving inland in the wake of the tanks and the other two regiments.

As one British historian noted, “For the 12th Infantry Regiment, the going was, if anything, worse as they crossed the inundations behind the Grand Dune and half-swam toward La Galle and Ste. Marie-du-Mont. By 1300 hours, contact was made with the airborne forces and by nightfall, the bridgehead was secure. To those who took part, it seemed incredible that the 8th and 22nd Regiments should have lost only 12 men, and that the total casualties of the division on that first day in Europe amounted to 197.”

At the end of the day on June 6, 1944, 1,700 vehicles and nearly 23,250 American soldiers had landed on Utah Beach.

4th Infantry Gets a Lucky Break

That night, at least one aid station had been established, first in a large shell crater and then farther forward near a knocked-out German bunker. Battalion surgeon Captain Walter E. Marchand recounted large numbers of wounded men that he and his staff had treated since shortly after the landing: “Finally, we got all of our aid station together—we were all exhausted—and we were so tired we just fell down and fell asleep, with artillery, mainly enemy, going overhead, most of it, fortunately for us, being directed toward the beach. This is the end of D-Day. It was hectic from the start.”

The following day, the Germans—actually Georgian soldiers serving in German uniforms and belonging to Ost Battalion 795, 709 Infantry Division—were still stubbornly holding out at Fauville and keeping the Americans at bay with heavy machine-gun and artillery fire they called in.

On the right flank of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, MacNeely’s 2nd Battalion, operating in coordination with Lt. Col. Ben Vandervoort (2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry), seized nearby Ecoquenéauville, half a mile east of Fauville, forcing the Germans to abandon Fauville, thus clearing National Road 13 and ending resistance in the area.

Earlier on D-Day, van Fleet’s 1st Battalion hurried up Causeway 3 toward Audouville-la-Hubert, which they found was already in the hands of the 502nd Parachute Infantry.

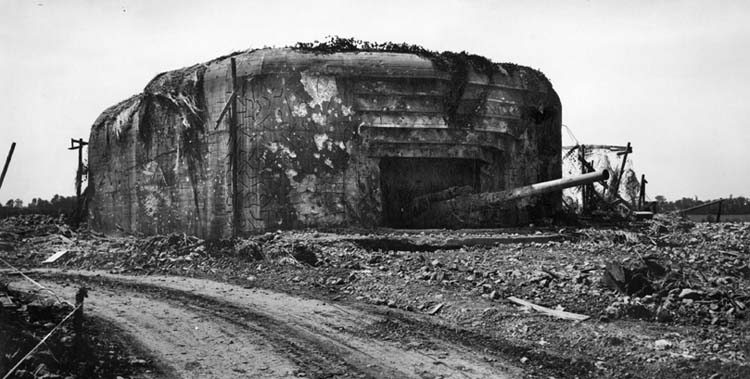

Had it landed at the originally intended site, the 4th Infantry Division would have had tougher going, for close to that stretch of beachhead was the Crisbecq Battery (sometimes called the St. Marcouf Battery), one of the most powerful gun batteries in Normandy. It covered the shoreline between St-Vaast la Hougue and Pointe du Hoc.

The site had three 210mm Skoda naval guns, two 20mm antiaircraft guns, six 75mm antiaircraft guns, and a 150mm tracer cannon. On D-Day, however, only two of the 210mm guns had been installed and protected by concrete casemates, as the third casemate was still under construction.

On June 5, the U.S. Army Air Forces had dropped 13,000 pounds of bombs on the battery, which destroyed all the antiaircraft guns around the position and killed a large number of personnel. The remaining troops of Oberleutnant zur See Walter Ohms’s battery nonetheless manned their larger guns, and on June 6, they sank the American destroyer USS Corry. Counterbattery fire from warships demolished most of the other casemates and artillery pieces.

A crewmember in the forward engine room of the Corry, Grant Gullickson, recalled, “All of a sudden, the ship literally jumped out of the water; the floor plates came loose, the lights went out, and steam filled the space. It was total darkness, with severely hot and choking steam everywhere. We figured that this was it, that our grave was to be the forward engine room on the Corry.

“The water reached … up to our waist, but the steam had stopped…. We evacuated through the hatch, and by the time we got up on deck, the main deck was awash…. The deck was ruptured clean across. It was obvious that the Corry was dead.” Gullickson and several of his crewmates managed to abandon the ship and float until picked up by another destroyer, but 24 crewmembers of the Corry had lost their lives.

The Ivy Division’s Legacy

While the Ivy Division was enjoying what has been described as being the military version of a cakewalk, the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions, assaulting Omaha Beach 20 miles to their east, were getting the hell kicked out of them by much stronger German resistance. Between the two beachheads, where a large battery posed a danger to the landings, the Rangers were climbing the cliffs at Pointe-du-Hoc and fighting desperately against the defenders, even though the guns there had been removed some weeks earlier.

On June 7, the Crisbecq Battery was still holding out. Every time the 4th Division troops tried to assault the position, Ohms called in fire from a neighboring battery at Azeville that broke up the ground attack. Over the next four days, continual attacks were repelled with heavy American losses. Finally, on June 11, Ohms was ordered to withdraw his 78 surviving men to the north, abandoning the battery. (Today the site is a museum.)

As June 7 wore on, the skies were filled with combat gliders swooping in with additional troops, weapons, equipment, and supplies. Although many gliders crashed upon landing, those that made it were contributing to the overwhelming success of the landings on the Utah beachhead.

After relieving the isolated 82nd Airborne Division at Ste. Mère-Église, Barton’s men were in continuous action, fighting through the hedgerows, clearing the Cotentin Peninsula, and taking part in the capture of Cherbourg on June 25. The Germans had totally wrecked the port before surrendering, and it took many weeks to repair it. During the period starting June 6, the 4th Infantry Division sustained more than 5,450 casualties, with more than 800 men killed.

After engaging in heavy fighting near Periers from July 6 to 12, the 4th Division broke through the left flank of the German Seventh Army, helped stop the German drive toward Avranches, and by the end of August had moved to Paris, assisting the French in the liberation of their capital. The 4th, in fact, was the first American division to reach Paris, but it stepped aside to allow Free French forces under General Charles de Gaulle to have the honor of liberating the City of Light.

The division would then take part in innumerable battles across northern Europe: fighting in the Hürtgen Forest in September 1944 (on September 11, a patrol from the division’s 22nd Infantry Regiment became the first American unit into Germany), fighting in Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge, and crossing the Rhine at the end of March 1945. Its wartime commander, Raymond Barton, became seriously ill during the Battle of the Bulge and had to be relieved. The 4th returned to the United States in July 1945.

Once Overlord had succeeded, Eisenhower wrote, “Our good luck was largely represented in the degree of surprise that we achieved by landing on Utah Beach, which the Germans considered unsuited to major amphibious operations.” Ike’s words were a fitting tribute to the officers and men of the Ivy Division.