By Richard L. Sherman

For William “Red” Verzola, Friday night was the liveliest night of the week. That was when a group of soldiers from Camp Myles Standish in Taunton, Massachusetts, made their regular pilgrimage to Charlie Pino’s Victory Club, just up the road in the tiny town of Norton, to enjoy a few beers and a couple of hours of relaxation. Red was actually an ex officio member of the group—a soldier, to be sure, but one who had marched to a slightly different drummer. The year was 1944, and the 24-year-old camp cook who had fought beside General Erwin Rommel in Africa was an Italian prisoner of war.

Humane Treatment for POWs Confined to the United States

By 1944, Italian POWs were being treated differently from other Axis prisoners. Italy had been reclassified as a “cobelligerent” after it surrendered in 1943. While Italian POWs remained confined, many of them were assigned to an Italian Service Corps and performed noncombat duties for the U.S. military. In this new role, the Italians enjoyed a good deal of freedom. Red Verzola even wore an American uniform outside camp.

For Nazi POWs, as well as the handful of Japanese POWs confined in the United States, life was not much tougher. By every measure, they were infinitely better off than either their erstwhile comrades in arms or their Allied counterparts, who remained in harm’s way on battlefields around the world.

It was an irony that irritated many Americans, particularly those unaware of the Italians’ new status. Scores of indignant citizens wrote to civil and military authorities to protest such spectacles as Italian soldiers being escorted to the opera in San Francisco and white-jacketed porters serving lunch to Nazi POWs as they rolled across America in comfortable Pullman cars.

Yet, while the complaints were understandable, there is no doubt, in retrospect, that America’s treatment of its POWs served the nation well, both in wartime and in the healing years beyond.

In practice, the humane approach reflected not only America’s moral sensibilities, but also its unswerving commitment to the terms of the 1929 Geneva Convention, which codified the treatment of prisoners of war.

Colonel A.M. Tollefson, assistant director of the POW division of the Provost Marshal’s office, delivered a response to the protesters that was more pragmatic than pious. America intended to play by the rules, he said, and in so doing avoid giving “even the semblance of an excuse to the enemy to violate the rights of American soldiers whom they hold as prisoners of war.”

A Manpower Windfall for the States

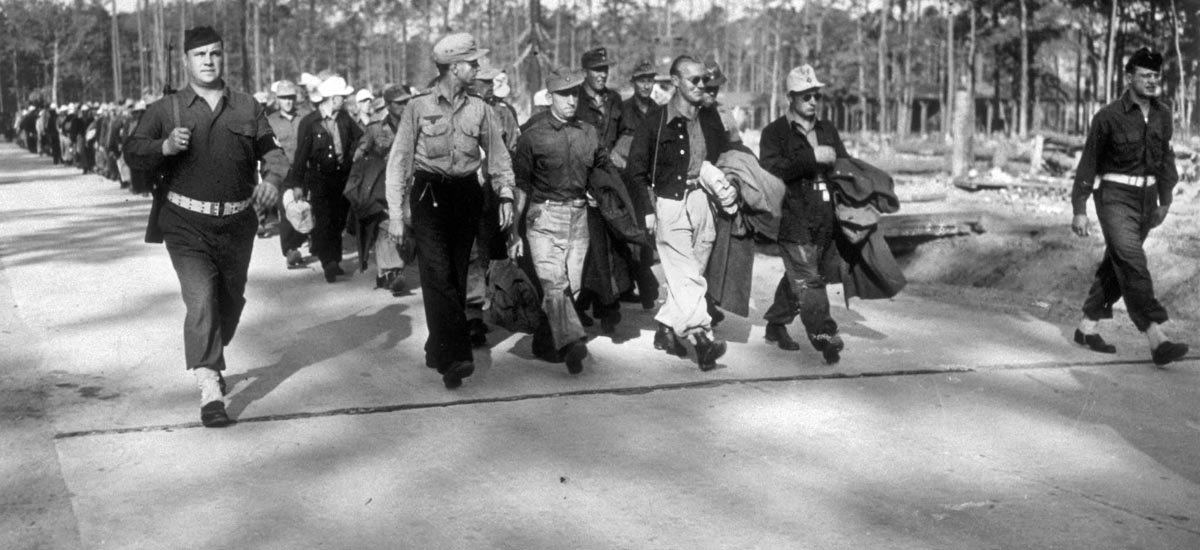

Diplomacy aside, there was a practical upside to the influx of POWs. The 425,036 Axis captives who flooded America—378,156 Germans, 41,456 Italians, and 5,424 Japanese—represented a huge manpower windfall for a nation struggling with the wartime decimation of its workforce.

Since the Geneva Convention allowed prisoners to be assigned nonmilitary duties, the prisoners were put to work. For three productive years, they picked grapes and cotton. They worked at canneries, food processing plants, and foundries. They packed meat, planted crops, and chopped trees. By late 1945, more than 115,000 prisoners were working in agriculture alone, and when they finally went home they were sorely missed by the American farmers who had not only come to rely on their services, but in many instances had become their friends.

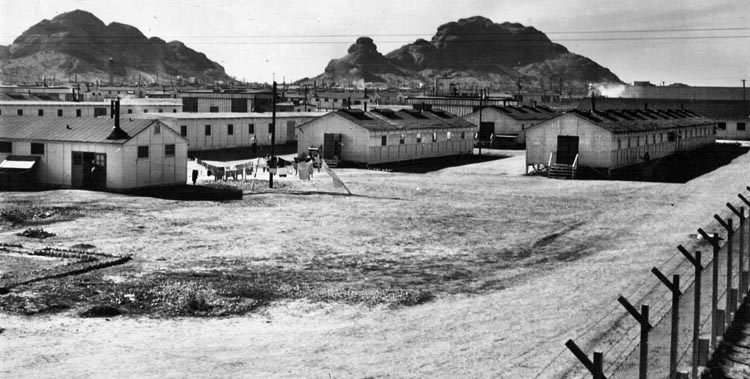

As it did in every facet of mobilization, from building Liberty ships to recruiting air raid wardens, the United States responded with remarkable alacrity to the flood of Axis prisoners. Camp Concordia in north central Kansas was typical of the 155 full-scale POW camps that mushroomed across America in the early years of the war. Concordia, with its 280 barracks and 23 auxiliary buildings, including a gymnasium, library, and 350-seat theater, rose from the plains in just 90 days at a cost of $1.8 million. By war’s end, 5,300 prisoners had spent time there, many of them working on neighboring farms.

Some camps did double duty. Red Verzola’s temporary home, Camp Myles Standish, served as both a POW camp and staging facility for the Boston Port of Embarkation. The whirlwind pace that characterized other aspects of mobilization was clearly evident at Myles Standish. The Army announced construction plans in June

By October, the 1,600-acre compound, built to accommodate 10,000 troops, was up and running, even though workers had to take time to move 36 private homes from the site during the course of construction.

Besides the full-scale camps, the Army set up 511 auxiliary prisons in cities and towns across the nation—facilities as modest as the two-story brick building in downtown Peabody, Kansas, that had previously housed a car sales agency.

The camps were designed for security as well as utility. Specifications called for the prototypical campsite to cover 350 acres, to be located no more than five miles from a railroad and no fewer than 500 feet from any “important” public thoroughfare. For security purposes, all trees, shrubs, and tall grass were to be removed. The terrain was to feature a moderate slope to facilitate drainage.

Generous Accommodations Provided by Uncle Sam

It would be hard to argue that Uncle Sam did not go to extraordinary lengths to treat the nation’s “guests” fairly. When there was not enough space to house both the prisoners and the guards, the existing barracks remained empty until additional facilities became available. In the interim, guards and prisoners alike lived in tents, again honoring the spirit of the Geneva accords, which mandated like accommodations for prisoners and guards.

Once settled in their new surroundings, the prisoners were treated generously. Their valuables were inventoried, labeled, and packaged. They were issued personal articles ranging from towels and toothbrushes to hair clippers and shoelaces. While supplying hard liquor would have been excessively indulgent, even by generous American standards, the prisoners nevertheless were allowed to purchase 3.2 beer and light wine on their own. They also received the identical medical and dental treatment provided to U.S. troops, including vaccinations and regular examinations to identify and treat communicable diseases.

Camp supervisors even counted calories: 2,000 a day for “non-workers,” 2,500 for ordinary workers, and 2,850 for “heavy” workers. And camp cooks were allowed to prepare food according to the tastes of the prisoners.

As if all that were not enough, the prisoners were paid 80 cents a day for their labors and granted access to canteen supplies such as candy and tobacco, recreational equipment, and handicraft and fine arts programs. They could also receive visitors twice a month, a privilege much appreciated by prisoners with relatives in the United States.

Escape Was Still on the Minds of Many POWs

Despite all this, a certain number of internees opted for freedom. Official records disclose that 2,827 managed to escape, climbing fences, digging tunnels, riding out of their compounds on service trucks, or simply walking away from work details. Most were rounded up within 48 hours.

The most spectacular breakout occurred in December 1944 at Papago Park on the outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona, where 25 U-boat crewmen dug a 200-foot tunnel and escaped into the barren mesquite country. All were recaptured.

In the end, U.S. authorities failed to account for just one escaped prisoner, a former German draftsman named Georg Gartner. So extraordinary was his achievement that he later wrote a book about it.

It was no wonder that the escapees did not last long on the outside. Few spoke English, and those who did were encumbered by suspicious accents. For most, the road to freedom was long and disheartening given the size of the country, the distance between oceans, and the nagging realization that even if they could pull off a logistical miracle, life was a whole lot better in the camps than back home.

Once outside, many of the prisoners acted like the Three Stooges. In his definitive Nazi Prisoners of War in America, Professor Arnold Krammer recalls a couple of bizarre incidents, one involving two Afrika Korps alumni who escaped a Texas camp wearing their desert uniforms—khaki shirts and shorts. Picked up by a friendly motorist, the escapees explained in heavily accented English that they were Boy Scouts en route to an international convention in Mexico. Eyeing the pair—one a six-footer, the other a stocky fellow with a substantial abdomen, both with suspiciously knobby knees and hairy legs—the motorist drove them directly to the authorities.

Balky prisoners, including recaptured escapees, faced only token punishment. At Camp Campbell, Kentucky, Krammer recalls, 20 Germans were found guilty of indolence, arrogance, and property damage (carving swastikas on trees). They were confined for seven days on bread and water. One worker with an attitude problem was deprived of beer and shows for one month. For a recaptured escapee, 30 days on bread and water was considered a tough sentence.

Nazi POWs: A Small But Militant Group of Zealots

Despite this indulgent atmosphere, the camps did spawn some ugly moments, most of them initiated by the small but militant percentage of Nazi zealots who infected the prison population. To the extent that they could identify the troublemakers, military authorities separated these hard cases from the rest of the prisoners, shipping 4,500 of them to Camp Tonkawa in Oklahoma. Conversely, they dispatched about 3,300 anti-Nazis to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and Camp Campbell. But they could not prevent the occasional incident. In a particularly sobering footnote to the nation’s POW experience, 14 of the hardliners were hanged at war’s end on gallows erected in an old salvage warehouse at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for killing fellow prisoners at camps in Oklahoma, Arizona, and South Carolina.

Military records describe an incident at Fort Knox, Kentucky, in November 1944—a clash between Nazis and anti-Nazis that ended in a confrontation between the Nazis and a young American guard. Under pressure, the guard fired his automatic weapon at a group of prisoners milling around near a perimeter fence. One prisoner died, and several were wounded. The Army’s hearing on the incident generated 107 pages of testimony. Accounts were drawn from everyone even remotely involved, including the wounded Germans. While in the end the guard was absolved, it is doubtful that any other government would have devoted more time and energy to a case involving unruly prisoners of war.

For some internees the prison experience turned out to be surprisingly propitious. Red Verzola, for example, met Catherine Pellegrini during a camp-sponsored visit to her home in Mansfield, 10 miles from Myles Standish. The two fell in love, and Catherine accompanied Red back to Italy at war’s end. When Red got his paperwork in order, the couple returned to the United States and settled in Mansfield. Red went to work for the Gilbane Construction Company of Providence, and the couple raised four children, one of whom graduated from the Air Force Academy.

In Kansas, a number of farm families stayed in touch with the prisoners who had worked their farms during the war years. In a recent Camp Concordia retrospective, the Wichita Eagle caught up with ex-Afrika Korps officer Franz Kramer while he was paying a sentimental visit to Kansas, one of several he had made since the war. Interned at Concordia, he had worked on the farm of Joe and Clara Melhus, about 15 miles from the camp.

“We ate with the family right here in the farmhouse,” he recalled. “We had lunch and dinner with Clara and Joe, served on their dining room table. Joe and Clara were very nice to us.”

Gunther Schroer, another Afrika Korps alumnus, recalled his Kansas years in the warmest of terms. One of his assignments took him to the Klaassen farm in Whitewater, where he and three other prisoners did farm work in the fall of 1944. Prisoner and farm family bonded and kept in touch for years after Schroer had returned to his native Essen, which had been devastated by Allied bombers. (Get a deeper look inside the fighting in the European Theater with WWII History magazine.)

Food was in such short supply in Essen that Schroer wrote to the Klaassens for help. The kindly Mennonite Kansans responded by sending Schroer packages of flour, rice, and corn. In the years since the war, the Klaassens and Schroer have nurtured the bond they forged in those unusual times. They met in Holland in 1977 and again in Kansas, when Schroer returned for a visit, laden with gifts.

A Nation and its Citizens Divided

Such sentimental anecdotes abound. Still, at the height of the war, plenty of Americans resented the nation’s POW policies, and media reports did little to mollify them. Reposing in the National Archives are clips from such major newspapers as the New York Times, Washington Post, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and Dallas Times Herald trumpeting such headlines as “Axis Prisoners Find Ease in Tennessee” and “Are We Coddling Nazi Prisoners?” Influential columnist Walter Winchell joined the chorus. Prisoners were said to be relaxing beside swimming pools, smoking free cigarettes, basking in “country club conditions,” and enjoying free hearing aids and sumptuous holiday dinners—including, one paper clucked, pineapple fritters.

Scores of letters from indignant citizens are preserved in the National Archives.

“I am terribly upset,” wrote Sam Solomon of Brooklyn, “to see a group of Italian prisoners in their shining, brand new uniforms being conducted on sightseeing tours of Manhattan. Then there are the ones in a camp near Camden (NJ) allowed the freedom of the city without guards.”

Mr. Solomon added that his nephew lived in upstate New York, where Nazi POWs were “a pampered lot of hoodlums who refuse to work. What are we running here, anyway,” he asked, “a kindergarten?”

But Edith Morse of Pittsburgh was just plain indignant after sharing a train ride with four Nazi POWs and their guard. Ms. Morse was scandalized to see porters serving lunch to the Germans, “who seemed to have a Pullman car all to themsevles.”

The prisoners, she said, were “arrogant and contemptuous, which one could understand when it’s considered that they traveled better than they could have in their own country.”

On that last count, one POW, Reinhold Pabel, was in full concurrence. Pabel, Krammer recalls, arrived in Norfolk, Virginia, in January 1944 after crossing the Atlantic on the Empress of Scotland.

“Most of us had been transported in boxcars during military service,” he recalled. “These modern, upholstered coaches were a pleasant surprise to everyone, and when the colored porter came through with coffee and sandwiches and offered them to us as though we were human beings, most of us forgot those anti-American feelings that had accumulated.”

Not all prisoners became converts. Krammer cites the testimony of one dedicated Nazi, Henry Kemper, who offered this bizarre recollection of his train ride from New York to Arkansas. “All we had to eat was orange jam, which they deliberately gave us to make us sick. A few of the older men died. I saw [the guards] throw the dead bodies off the train.”

Another German postulated that the trains carrying prisoners to the camps were carefully routed around the cities he was sure had been leveled by the Luftwaffe.

Hardliners who believed America had been ravaged must have found it difficult to reconcile the evidence of their own eyes as they peered out of the windows of trains that carried them through towering cityscapes, sleepy towns, and tranquil stretches of prairie en route to their prison camps.

But the hardliners were a minority. By war’s end, many Germans had come to respect their captors and appreciate the blessings of democracy. U.S. authorities had done what they could to encourage these feelings. Among the diversions offered the prisoners was an education program that promoted the merits of the American system. An exit poll of 22,153 POWs conducted by the Provost Marshal General’s office showed that 74 percent of the prisoners left the United States with an appreciation of democracy and a friendly attitude toward their captors.

The program, of course, had an obvious long-term objective. U.S. authorities were aware that the prisoners would exert a powerful influence on German public opinion during the peace to come.

Generations after Hiroshima, millions of surviving Americans share memories of the war, some poignant, some bitter. It is easy to understand why so many of them resented America’s propensity for “coddling” the POWs. Yet even the hardest of hearts would have to concede that American benevolence was not only a nonnegotiable moral imperative, but also a significant catalyst for the restoration of normal relationships among once intractable foes.

As New York University Professor Robert Hoppal asserted in a wartime letter to the Secretary of War, “The best way to build a peace is to be decent to the strangers within our gates.”

Author Richard L. Sherman resides in North Attleboro, Massachusetts. This is his first contribution to WWII History.