By Victor Kamenir

Well before the great Viking siege of Paris, more than 300 islands dotted the length of the Seine River, reduced over the centuries by human impact and natural changes to slightly more than 100. During the Iron Age, the Celtic tribe of the Parisii made their home around a cluster of islands at the spot four miles downstream from where the Marne River joins the Seine. After conquering Gaul, the Romans built the city of Lutetia atop the ruins of the old Parisii settlement. Due to its location at an important road nexus, Lutetia grew in importance, becoming the capital of the Roman Western Gaul province by the end of the 4th century.

For protection from barbarians migrating into Gaul, the Celts living along the banks of the Seine at Lutetia relocated to the two largest islands in the river, named the Ile de la Cité and the Ile de St-Louis. Using stones recovered from damaged buildings, the Romans built defensive walls on the 56-acre Ile de la Cité. The Ile de St-Louis, which was roughly half the size of the neighboring island, was used mainly as pastureland and left undefended.

The defensive walls largely followed the outline of the island. The builders attempted to place the walls as close as possible to the water’s edge, but the marshy and muddy banks of the Ile de la Cité permitted only approximately half of the island to be enclosed. Due to the uneven terrain, the actual height of the walls varied from 12 to 25 feet, placing the top of the wall at roughly uniform level. Eight feet thick at the base, the walls tapered to six feet at the top. The Seine River with its swift current acted as a natural moat over which two bridges anchored on the Ile de la Cité connected the two sides of the river.

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the name of the town reverted to Civitas de Parisiis and was eventually shortened to Paris. During Charlemagne’s reign, Paris became one of the most important cities of the Frankish Empire. Charlemagne’s conquest of Saxony in the late 8th century brought the borders of his empire into direct contact with Danish kingdoms. The collapse of centralized Danish monarchy around the beginning of the 9th century coincided with the explosion of Scandinavian expansion, which was spurred by the innovations in Scandinavian shipbuilding.

Raids by Scandinavian pirates against Western Europe began in the late 8th century, with the attack on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne off the northwestern coast of England in 793 ushering in the Viking Age. The term “Vikings” as we know it appears to have originated in the 18th century. Their Western contemporaries typically referred to Scandinavian pirates and raiders as the Norse or the Danes. In Eastern Europe, the Vikings were typically called the Rus in reflection of their Swedish origin. Lasting until the end of the 11th century, Viking raids took place over a vast territory from the Western European seaboard to the Black and Caspian Seas in the East and the Mediterranean Sea in the South. Sailing the inshore waters of the North and Celtic Seas and the English Channel, the Vikings were within easy striking distance of rich targets in the British Isles and Western Europe.

The Vikings built shallow-draft vessels known as longships. They used their longships not only at sea, but also to penetrate large land masses by rowing them upriver. The longships, which could pass through water just a few feet deep, were light enough to be portaged short distances when necessary. The symmetrical design of the Viking boats allowed them to reverse course without turning, a feature especially useful within the relatively narrow confines of a river. With emphasis on speed and maneuverability, the main source of propulsion was by oar, but a square sail was added when traveling on the open sea.

The Vikings initially raided in one to three ships; however, as they grew in power and their raids became more ambitious, their fleets grew to as many as 200 longships. But these great fleets were the exception rather than the rule. Due to the shallow hull construction of their ships, the Vikings could land directly on the beaches or river banks. This allowed rapid egress and prepared the Norsemen to strike where they were least expected. After initially raiding coastal areas, the Vikings began penetrating deeper inland using rivers as highways.

Raiding was a young man’s business, a sort of rite of passage to earn reputation and wealth. Once having started a family, the majority of former Vikings settled down to farming, the primary means of earning a living in Scandinavia. The Icelander Egil’s Saga describes its Viking protagonist, Egil Skallagrimsson, as conducting both trading and raiding.

Virtually all Viking activities depended on exploration and navigation of seas and rivers. Shipbuilding was expensive, and only rich men like kings and earls could afford to build or buy and outfit a ship or fleet of ships. Those with lesser means could buy a share in a longship, while those without means served as warriors or crewmen.

During the heyday of the Viking Age, a typical force of Norse raiders consisted of approximately 400 men. Large fleets usually did not have central command, being a conglomeration of war bands with their own leaders. Operating in the manner of modern-day commandos, they avoided pitched battles with local forces in favor of quick, hard strikes against specific targets and fading away before local response could be organized. When forced to fight in an open field and with the battle going against them, a Viking war band would give way and scatter, avoiding crippling losses and reforming at a different location.

In 882 a relief force of Franks pursued the Vikings, who “betook themselves to a wood and scattered hither and yon, and finally returned to their ships with little loss,” according to the Annals of St. Vaast, a collection of historical records produced in the 10th century by the Abbey of St. Vaast in Arras.

When staying in one location for a period of time, the Vikings encamped on river islands or on easily defensible river banks. Since longships were not designed to carry horses, the Norsemen captured or bought horses from local residents. The horses allowed them to raid deep inland.

The main goal of a Viking raid was to carry off portable valuables and slaves. It was a common tactic for Vikings to demand tribute of gold, silver, or foodstuffs in exchange for sparing a town from looting. After gathering plunder in one place, the Vikings frequently sailed to another location. Here they would trade their loot with the locals and return to raiding farther down the line.

The Vikings regularly targeted churches and monasteries because they held considerable wealth. The well-known vulnerability of religious institutions made them attractive targets. In the course of plundering these ecclesiastical institutions, the Norsemen would indiscriminately slaughter monks and clerics. While Christian combatants, for the most part, left churches and holy sites unmolested, the pagan Norsemen harbored no such inhibitions.

The first Viking attack against Charlemagne’s empire came in 799. Charlemagne responded by establishing a defensive system the following year north of the Seine estuary. The Franks fortified key coastal locations and conducted regular ship patrols in river estuaries. This initially helped prevent Viking river raids.

After Charlemagne’s death in 814, his empire was divided among his three sons. The power struggle among his progeny prevented the Franks from bringing the full weight of their defensive resources against the Viking menace. By the middle of the 9th century, the Vikings had firm control of large parts of France’s northern coast and regularly raided along the Seine and Loire Rivers.

The Vikings eventually began colonizing large swaths of territory in the lands they regularly raided. They built settlements in England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Scotland, and northern France beginning in the 9th century. Local rulers frequently made treaties with strong Viking chieftains, bestowing land grants and hiring Viking mercenaries. In some internecine clashes between Frankish domains, Viking war bands served on both sides.

The Vikings established a particularly strong presence in Neustria, the northwestern Frankish territory that extended from the Loire River to the south of modern Belgium. A powerful Viking chieftain named Rollo controlled the Seine estuary and territory as much as 50 miles inland. This put Paris within easy striking distance.

The first Viking attack on Paris came in 845 under the war chief Reginherus. After plundering the city, the Vikings withdrew after King Charles II the Bald of West Francia paid an exorbitant ransom of almost 5,200 pounds in gold and silver. The Vikings returned three more times in the 860s but withdrew after being bought off with sufficient bribes while looting the surrounding countryside and burning churches.

Charles eschewed battle with the Vikings; instead, he channeled his resources toward the construction of fortifications along the Seine and other rivers that would prevent the passage of Viking longships. In his Edict of Pistres in 864, the King of West Francia detailed the need to strengthen key locations in France against the raids. He ordered fortified bridges constructed at all towns on major rivers to prevent Viking longships from passing beyond them.

In addition, Charles the Bald revamped the lantweri system under which all able-bodied men were required to report for service against the invaders. The king forbade his people from trading in arms and horses with the Norsemen. He made selling or trading horses with the Vikings a crime punishable by death.

The pattern of Viking raids changed by the time another large host of Norsemen arrived at Paris in 885. King Alfred’s last Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex in Great Britain withstood the Viking onslaught, while large parts of the kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia, and East Anglia were divided between powerful Viking leaders, forming an extensive swath of territory called the Danelaw. With no new profitable territory to conquer, those Viking war bands yet to gain their fortune turned their attention to the European continent.

A large coalition of Viking forces assembled in the territory controlled by Rollo in July 885 in preparation for a large-scale campaign against West Francia. The main forces belonged to Rollo and Earl Sigfred, another powerful chieftain, who were joined by several smaller bands. Neither Rollo nor Sigfred was in overall command of the assembled host. The combined Viking forces first sacked Rouen, after which they advanced against Pont-de-l’Arche, a fortified bridge on the Seine River 10 miles southeast of the city. A small body of Frankish troops under the command of Count Ragenold, Margrave of Neustria, assembled at the bridge to oppose the Vikings. The Vikings soundly defeated the Franks at Pont-de-l’Arche on July 25, 885. Ragenold was slain in the sharp clash.

On the move again in early November after solidifying their hold on Rouen, the Vikings advanced overland and by river to the fortified bridge where the Oise River joins the Seine. Easily capturing the bridge on the Oise, the Vikings continued to Paris. As they drew closer to Paris, the locals began fleeing their homes to safety deeper inland or taking shelter behind the walls of Paris on the Ile de la Cité, bringing their valuables and foodstuffs with them.

Among the refugees taking shelter in Paris was a young Benedictine monk named Abbo Cernuus. Abbo was a monk at the Abbey of St-Germain-des-Prés. He came from the region between the Seine and the Loire and was in Paris during the siege. A decade later Abbo wrote an extensive Latin poem called Bella Parisiacae Urbis describing the events that unfolded at Paris in 885-886. While the verse is at times exaggerated, flowery, and grandiloquent, Abbo nonetheless supplies many crucial details about events that could only have been provided by a witness.

Arriving before Paris on or about November 25, 885, the Vikings under Rollo and Sigfred found their way upriver barred by two low-slung fortified bridges. The shorter bridge, the Petit Pont, which linked the island to the south bank, was constructed of wood. Its bridgehead was fortified by the Petit Chatelet, a wooden tower. The longer, northern span, known as the Grand Pont, was made out of stone, with crenellations along its length. Its bridgehead was defended by the stone Grand Chatelet, which was only partially completed. Nevertheless, its foundations were solid and stood firmly grounded. Catapults and ballistae mounted on city walls could take under fire any ship attempting to reach the Ile de la Cité along either channel of the Seine River.

Count Odo of Paris and Bishop Gauzlin of St. Denis directed the defense of Paris on behalf of King Charles. Odo was an experienced warrior whose father, Robert the Strong, Count of Anjou, was killed on July 2, 866, in a clash with a force of Viking-Breton raiders at Brissarthe on the right bank of the Loire. Gauzlin had no love for the Vikings, having been captured in 858 with his younger brother Louis. The Norsemen released their captives upon payment of a substantial ransom.

The force defending Paris was a meager one. In addition to a handful of nobles, there were approximately 200 troops, according to Abbo. He was most likely only counting men-at-arms trained for war. With this in mind, there might also have been lightly armed spearmen and crossbowmen from the local militia. These men would have handled mundane tasks such as standing watch and hauling supplies.

When it became apparent the Vikings were threatening Paris itself, preparations began in earnest. “For very hastily arrows were being sharpened, repaired, forged, and bucklers were all sorted out; even old arms were restored,” wrote Abbo. “Seven hundred high-prowed ships and very many smaller ones, along with an enormous multitude of smaller vessels” sailed up the Seine carrying 40,000 Norsemen, according to Abbo. A more accurate estimate, though, is that the Viking army consisted of 12,000 men traveling in 300 ships.

Rather than demanding tribute from Paris, Rollo and Sigfred initially requested free passage up the Seine River. “Give us your consent that we might go our way, well beyond this city,” they purportedly said. “Nothing in it shall we touch, but shall preserve and safeguard.” To add weight to their request, the Vikings threatened to attack Paris if free passage was refused. Co-commanders Odo and Gauzlin, unfazed by the threats, flatly refused to accommodate the Vikings.

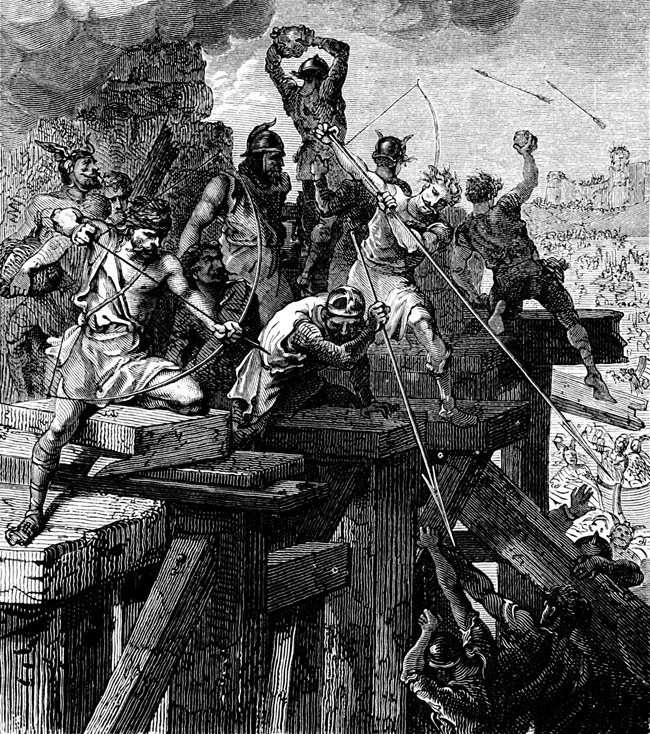

Having been refused passage, the Vikings attacked on November 26. They sought to overwhelm the defenders in a single, furious assault. Vikings armed with swords and axes assailed the towers guarding the two bridges. They were supported by Viking archers in the longships on the river who showered the defenders with arrows. Another large body of Vikings landed on the Ile de la Cité and attempted to scale the city walls.

Furious fighting erupted all around the city, especially at the towers. Braving Viking archers in the boats, defenders rushed reinforcements to the towers. Especially heavy fighting broke out at the Grand Chatelet. Unable to break down the gates, a group of Vikings attacked the base of the tower with picks. The defenders “served them up with oil and wax and pitch, which was all mixed up together and made into hot liquid on a furnace,” wrote Abbo. Engulfed in flames, Vikings struck by the fire writhed on the ground, while others jumped in the river to extinguish the flames. More Vikings joined the fight at the Grand Chatelet as defenders fired arrows and dropped stones on the crowd of attackers at the bottom of the tower.

After several hours of fighting in which they failed to gain a foothold in any place, the Vikings withdrew. They fell back, taking their dead with them. The Vikings had some female family members with them on the campaign, and the women began heckling their men for retreating. A number of Vikings renewed the attack against the Grand Chatelet and attempted to set its gate on fire, as their “[women’s] rude mouths drove them to make their own domed furnace near the bottom of the tower,” wrote Abbo. The attackers made a breach in the tower’s foundation but were not able to break in against the defenders’ determined resistance. Likewise, the Vikings attacking the walls on the Ile de la Cité boarded their ships and withdrew. The defenders completed the upper story of the Grand Chatelet during the night using wooden planks.

During the next several days, the Vikings cut down a large tree, which they fashioned into a battering ram mounted on a wheeled frame with overhead cover. Once the ram was completed, the Vikings advanced against the Grand Chatelet, taking cover under the ram frame’s overhead protection and behind its large wheels. At the same time, more Vikings landed from their ships on the island and attacked the city walls. Both Count Odo and Bishop Gauzlin were in the thick of the fighting. They shouted encouragement to their men. Their very presence prevented panic. Gauzlin, firing a bow from the city wall, was lightly wounded by a Viking arrow. Despite their best efforts, the second Viking attack against Paris failed as well.

Recognizing that Paris could not be taken by storm, the Vikings settled in for a protracted siege and began raiding deeper into the countryside for provisions. In early December, they established a permanent camp on the right side of the river in the area of the modern-day suburb of Saint-Denis. Their camp was protected by stone and earth ramparts and a deep ditch bristling with sharpened stakes.

After looting the Abbey of St-Germain-des-Prés, the Vikings turned it into a stable for their horses. They also established an outpost on the left side of the river to blockade the Petit Chatelet. Like a horde of locusts, the Vikings stripped the countryside. In the process, they indiscriminately killed local residents who had the misfortune of falling into their hands.

“The Danes ransacked and despoiled, massacred, and burned and ravaged,” wrote Abbo. “The men in arms, in their keenness to flee, sought out the woods. No one stayed to be found; everyone fled.” Abbo lamented that the people of the countryside put up no opposition to the Vikings, allowing them to plunder at will. “The Danes took away on their ships all that was splendid in this good realm, all that was the pride of this famous region.”

As the Great Siege of Paris wore on, the Vikings constructed two additional rams and began building siege weapons that Abbo described as mangonels and catapults. They also removed a belfry from one of the churches and used it as a mobile tower, shooting arrows from its slits. Abbo says that the Franks attempted to interfere with these efforts by firing their own defensive weapons at the Vikings. “Then from the tower was launched a javelin, shot with great force and accuracy,” he wrote.

Whether the Vikings had siege engines is subject to debate. They likely had been exposed to siege engines in the course of their various campaigns against the Anglo-Saxons and Franks. Owing to the shallow draft of their longships and their initial intentions to raid farther upriver, it is highly unlikely that Rollo and Sigfred brought siege artillery with them. Instead, they would have detailed work parties to construct them on site. The siege weapons the Vikings built during the siege would have been of simple design and not the torsion-powered onagers or ballistas capable of knocking down stone walls. Such weapons did not arrive in northern Europe until the late 12th century.

Most fortifications in the early Medieval Era were made of earth and wood and would typically be brought down by fire and mining. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the skills of siege-engine building in Europe largely fell into disuse, and only the crudest forms existed. The siege engines known to the Vikings were most likely descendants of Roman field artillery pieces, basically slinging perrier engines and giant crossbows, for no engine in the medieval period depended upon torsion power. The term “mangonel” used by Abbo is derived from the Greek “magganon,” meaning “engine of war.” The term is frequently used interchangeably with any stone-throwing catapult, including the onager and ballista.

Once the Vikings had constructed a number of siege weapons, they launched another attack. “Into the city they hurled a thousand pots of molten lead, and the turrets on the bridges were knocked down by the catapults,” wrote Abbo. The new attack, both along the bank and from the river, was against the Grand Chatelet and the Grand Pont. The Vikings attacking the Grand Chatelet formed a testudo. “They advanced behind painted shields held up above to form a life-preserving vault,” Abbo wrote. “Not one of them dared lift his head out from under it. And yet underneath they felt constant blows.”

The defenders again rushed to the threatened areas, and defensive fire was taking a great toll on the attackers. Abbo says, “No path to the city was left unstained by the blood of men.” Numerous Frankish monks from the despoiled monasteries fought among the Paris defenders. Abbo described an incident during the attack when a Viking warrior was struck in the mouth by an arrow. A second man rushed to help him and was struck down in turn, and then a third man succumbed to the same fate before their comrades formed a wall of shields around them and pulled them to safety under the covering fire of their own archers. Abbo noted that the Viking arrows were poisoned. After several hours of fighting, this attack petered out as well.

Periodic attacks continued through December and into January 886, primarily directed against the Grand Chatelet. In the lull between the assaults, the defenders dug ditches around the tower, reducing the usefulness of the Vikings’ rams by making it difficult to drag them into position. To ease the approach of the rams, one group of Vikings would attack the tower, while others began filling in ditches with debris, animal carcasses, and the corpses of captured Franks.

To further counteract the battering rams, the defenders constructed so-called ram-catchers that they used to immobilize the ram’s log. “[These] hefty shafts of hard wood, each one pierced at the far end with a keen tooth of iron, with which to strike rapidly at the siege engines of the Danes,” Abbo explained.

The Viking assaults also came under fire from Frankish heavy weapons. For their part, the Franks also constructed mangonels using thick planks. These instruments of death and destruction “shot forth great, massive stones that landed cruelly, smashing utterly the humble shelters of the vile Danes; the brains of those wretches were battered out of their sculls,” Abbo wrote.

Failing to take the Grand Chatelet, the Vikings undertook a new tactic against the Grand Pont Bridge: They portaged three ships a short distance around the city on February 2, 886, and placed them back in the water upriver. The Vikings then loaded these ships with firewood and set them ablaze. “Spewing flames, these ships began to drift from east to west; they were guided and pulled by taut ropes along the river bank,” wrote Abbo. “The enemy hoped either to burn the bridge or the tower.”

The fire ships rammed into “a high heap of stones, so that no harm came to the bridge,” wrote Abbo. The defenders put out the fires with water from the river and then kept the hulks to use as they saw fit. During the attack against the bridge, the Vikings left the rams unguarded, so the Franks sallied forth from the Grand Chatelet tower and captured and destroyed two of them.

The siege of Paris dragged on through the winter, with rains adding to the misery of the besiegers huddled in their camps. During the night of February 6, the rain-swollen Seine River overflowed its banks, and the bridge supports of the wooden Petit Pont failed, leaving the Petit Chatelet tower isolated on the left bank. The following morning, the Vikings launched a strong attack against the vulnerable wooden tower, which was defended by just a dozen Franks. Braving the defenders’ arrows, the Vikings pushed a wagon loaded with hay against the tower and set it ablaze. Despite the defenders’ attempts to suppress it, the fire spread, forcing the Franks to retreat to the remnants of the destroyed bridge. The defenders formed a small shield wall bristling with swords at the bridgehead and braced for a fight to the death.

The Vikings promised to spare them if the Franks surrendered to be held for ransom. Faced with certain death otherwise, the 12 defenders laid down their arms. Believing a Frank named Eriveus to be a person of some importance, the Vikings bound him with ropes with the intention of ransoming him. The others, not so fortunate, were put to the sword by their captors. Seeing his comrades being slaughtered, Eriveus demanded to share their fate. The Vikings obliged him by slaying him the following day. They then tore down the remains of the burned tower and flung the bodies of the slaughtered defenders into the river.

With the obstacle of the Petit Pont removed, restless Earl Sigfred took his men on a major operation up the Seine River, raiding over a wide swath of the Frankish interior south of Paris, from Troyes to Le Mans. Believing the Viking camp on the right bank abandoned, Abbot Ebolus from the St. Denis Monastery sallied across Grand Pont with a small troop of soldiers intending to destroy the camp and free his despoiled home. But Rollo and his men were still in the camp, and Ebolus had to beat a hasty retreat back to Paris.

With the numbers of besiegers reduced by Sigfred’s departure and the environs of Paris being sparsely patrolled, Count Odo was able to send several messengers through enemy lines with requests for relief. He appealed for help to Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Fat, who was campaigning in Italy, and his senior military commander, Count Heinrich of Fulda. As the Margrave of Saxony, Heinrich was the senior Carolingian commander in East Francia and had led several successful campaigns against the Vikings in the recent past.

Responding to Odo’s call for relief, Count Heinrich arrived at the siege of Paris in March 886. He and his men were exhausted from having made a forced march in inclement weather. Heinrich led his Frankish troops in a surprise night attack against the Viking camp but was thrown back. After a few more days of desultory skirmishing, Heinrich withdrew to Saxony.

Shortly after Count Heinrich’s departure, Sigfred returned to Paris and added his men to the siege. Heinrich’s unsuccessful attempt to lift the siege and Sigfred’s return had an understandably adverse effect on the defenders’ morale. In late March, Odo and Gauzlin were forced to enter into negotiations with the Viking leaders; however, the negotiations with Odo fell apart when the Vikings made an unsuccessful attempt to kidnap him during the talks. Despite this, Gauzlin continued negotiations and reached a separate agreement with Sigfred. The agreement stipulated that the church would pay Sigfred 60 pounds of silver to vacate the Abbey of St-Germain-des-Prés and quit the siege of Paris. Abbo seems to have differentiated in his account between the church’s ecclesiastical authority and Odo’s administrative authority.

Gauzlin’s tribute came at an opportune time, for the Vikings did not have the temperament for long sieges, and their morale had dipped considerably. After taking possession of the silver, Sigfred led his warriors farther inland in search of more plunder.

Rollo continued his siege of Paris because he wanted to establish a permanent presence on the Seine River. He undertook another assault against the Grand Chatelet, but it was repulsed. As the siege dragged on, the situation inside Paris became dire, with an outbreak of plague carrying away many Parisians. One of them was Gauzlin, who succumbed to the plague on April 16, 886.

In late May 886, Odo himself slipped out of Paris, leaving Abbot Ebolus in charge of the defenses. Under command of the fighting abbot, the defenders conducted frequent nighttime sallies against Viking sentries and outposts and sometimes brought back prisoners who were executed after being questioned.

Count Odo returned to Paris in June 866 with a small body of fresh troops and some supplies, coming up from the direction of Montmartre. The Danes attempted to block his approach, but, aided by a sally from the Grand Chatelet, Odo and his men were able to fight through to Paris.

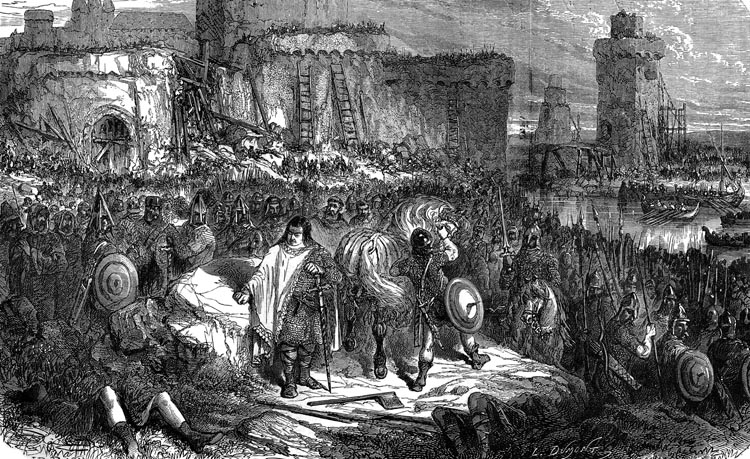

The Vikings launched sporadic attacks against Paris throughout the summer and well into the autumn. King Charles the Fat arrived in October 886 with a large body of troops drawn from various lands. To the chagrin of the Paris defenders, the king did not attack the Vikings but established his own camp on the heights of Montmartre and entered into negotiations with Rollo. Charles the Fat promised Rollo 700 pounds in silver, to share with Sigfred, if he were to lift the siege and withdraw. Since the sum was significant, Charles requested until March of 887 to gather the money. In the meantime, Charles promised the Vikings free passage to pillage the Duchy of Burgundy, which was in revolt against his authority.

After campaigning for several months in Burgundy, during which time they unsuccessfully besieged Sens, Rollo and Sigfred returned to Paris in late 886. True to his word, King Charles paid the tribute, and the Vikings finally withdrew from Paris. Sigfred moved on to Friesland, where he was later killed in battle.

Rollo fared much better. In addition to the monetary tribute, Charles the Fat gave Rollo a land grant along the lower Seine River. Rollo made Rouen his base. While similar land grants to other Viking chieftains eventually reverted to the locals, Rollo’s land grant remained in effect. The territory under his control was known as the land of the Norsemen, who became known as Normans. This region soon became the Duchy of Normandy. Rollo’s progeny and followers became more French than Danish, and Rollo’s direct descendent William the Conqueror came to rule England in the 11th century.

King Charles the Fat, loathed by Frankish nobles and notables for the shameful capitulation to the Vikings, died on January 13, 888. Count Odo, whose reputation had been enormously enhanced by his role in the defense of Paris, was elected king shortly afterward by the nobles of the realm. Odo was crowned king of West Francia in February 888. When a Viking force threatened Paris that summer, Odo’s troops defeated it at Montfaucon Forest on June 24, 888. Over the course of the next quarter century, Viking war bands appeared in the vicinity of Paris several more times, but they never attacked the city.