By Frank Jastrzembski

“Oh, the Lord, Henry but didn’t the Rebs get the devil sure enough,” Private Charles Grundy of the 10th Illinois Infantry Regiment wrote to a friend three days after the conclusion of the Battle of Nashville fought December 15-16, 1864. Grundy, an eyewitness to the battle, recorded his observations as he watched Union soldiers shatter the Confederate defenses. “The Rebs broke and fled in confusion, leaving everything they had[,] throwing away guns, knapsacks, and everything else, and our boys after them pelting shot and shell and bullets into their broken ranks, slaying them by the dozen[,] many of them wouldn’t run at all, but surrendered without moving from their works.” Grundy may have been a lowly Union private, but he did not need to be a general to realize that General John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee had ceased to pose any real danger to the Union Army in the western theater.

In consultation with Lt. Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard, Confederate President Jefferson C. Davis in September 1864 approved Hood’s ambitious plan to invade Union-held Tennessee. Hood hoped that by rapid marches he might be able to seize the railroad and supply hub of Nashville. If he could capture Tennessee’s capital, Hood reasoned, its citizens might revolt against Federal occupation, thus swelling his ranks.

Once Nashville was back under Confederate control, Hood intended to cross the Ohio River and do as much damage as possible in the heart of Union territory. Perhaps he might even be able to turn east and unite with General Robert E. Lee’s besieged army at Petersburg. Once together, they might fall on Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s rear. Once this unified Confederate force crushed Grant, it could then march on Washington, D.C. At that point, Lincoln would have no choice but to negotiate an end to the war.

It was a bold and audacious plan. The most far-fetched aspects of it were clearly beyond the realm of possibility at that stage in the war. But former U.S. Senator from Mississippi Davis was desperate for anything that could provide a spark to the Confederate war effort. He therefore reluctantly gave Hood his blessing.

Hood’s offensive into Tennessee was risky, but if it had succeeded it might have disrupted the Union war effort or even prolonged the war. Grant knew how important it was to destroy Hood’s menacing Confederate army. Initially at least, Hood’s offensive not only tied up Union troops stationed along the Mississippi River and prevented them from cooperating with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on his thrust into the Deep South, but it also posed a threat to Union-held Kentucky. If Hood could outmaneuver or outfight Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas at Nashville, Grant would have no choice but to redirect troops to contend with the Army of Tennesee. Grant was so troubled by the threat that he left Virginia and headed to Tennessee to ensure Hood’s defeat. “I was never so anxious during the war as at that time,” said the usually unflappable Grant.

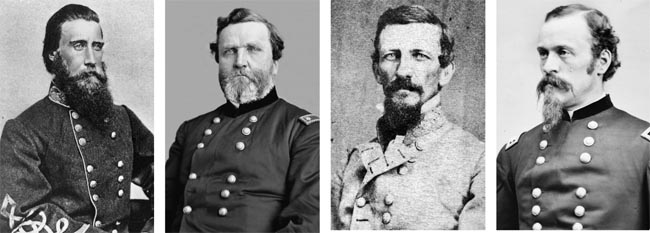

Hood, a 33-year-old Kentuckian, had earned a reputation by 1864 for his bravery, quick action, and ability to inspire his men. Hood was a courageous and efficient brigade and division commander when under supervision, but a poor independent commander. When left to his own devices, he was prone to indulge his impulsive nature, putting his troops at risk.

“Nobody doubted his bravery, but as to his judgment—that was another question,” wrote Lt. Col. Albert G. Brackett of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry. Hood’s career mirrored the careers of French Marshal Michel Ney and Austrian General Ludwig von Benedek, both of whom were promoted beyond their capacity for high command.

Hood ranked 44 out of 52 in the U.S. Military Academy at West Point’s Class of 1853. His first assignment upon graduating was in the harsh wilderness of northern California where the young second lieutenant of cavalry served for two years at Fort Jones. Hood led escorts for surveying parties journeying into the mountains near the Oregon border.

Second Lieutenant Hood joined the U.S. Second Cavalry Regiment on the Texas frontier in 1855. His superiors in the cavalry regiment included Colonel Albert S. Johnston, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, Major William J. Hardee, and, ironically, his future adversary at Nashville, Major Thomas.

Hood ran into trouble in a clash with Comanches in July 1857 at Devil’s River. Outnumbered four to one, his company lost six causalities in the badly handled encounter. In the desperate fighting, he was wounded in the arm by an arrow. His poor showing against the Comanches foreshadowed problems with independent command during the Civil War when the stakes were far greater.

Hood resigned his commission in 1861 to join the Confederacy. He subsequently was named colonel of the 4th Texas Infantry Regiment, which had the distinction of being one of only three Texas infantry regiments serving in Virginia. He performed ably and received his promotion to brigadier general on March 6, 1862. His brigade soon went by the nickname “Hood’s Texas Brigade.”

His performance at Gaines’ Mill on June 27 during General Robert E. Lee’s counteroffensive known as the Seven Days Battle earned him high praise. During that bloody clash along the banks of Boatswain’s Swamp, Hood led his Texas Brigade in a shock charge that pierced the Union center. After the campaign, Hood took over the division when Lee transferred Maj. Gen. William Whiting for his lackluster performance. Hood skillfully handled his division at Second Manassas in August 1862 and at Antietam the following month. As a result, he received a promotion to major general on October 11.

The challenge of leading from the front took a heavy toll on Hood’s body in hard campaigning in two of the most famous battles of the Civil War in 1863. On July 2 at Gettysburg a shell fragment struck Hood’s arm below the elbow, badly damaging the nerves and muscles and permanently depriving him of the use of his left hand. Despite the severe wound, Hood was at the head of his division when Lee sent Longstreet’s corps to north Georgia to assist General Braxton Bragg. It was there during the clash in the woods and fields along Chickamauga Creek that Hood was wounded in the right leg so severely that it had to be amputated four inches below the hip. He subsequently spent the winter of 1863-1864 convalescing in Richmond.

Hood had served ably under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet during 1862 and 1863, and there was every reason to believe he was capable of high command. He was therefore promoted to lieutenant general on February 11, 1864. The promotion was backdated to September 20, 1863, in recognition of his valor at Chickamauga. Hood was told to report to Georgia where he would take command of a corps in General Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennesee. Hood put in an average performance while serving under Johnston. Johnston favored manuever over head-to-head fighting. Of the Confederate generals serving under Johnston who questioned his conduct of the campaign, Hood was the most vocal critic.

Hood sent letters to the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, that were highly critical of Johnston; in so doing, he bypassed the official communication channels. Hoping to get to the bottom of the matter, Davis dispatched General Braxton Bragg, who at that point in the war was serving as the Confederate president’s chief of staff, to interview Johnston and make his own assessment of the situation. Hood kept up his criticism, informing Bragg that he believed that Johnston was ineffective. Hood was not alone, though, in this view of Johnston, for his fellow corps commander in the Army of Tennessee, Lt. Gen. William Hardee, also faulted Johnston for not bringing on a pitched battle before the Confederate army found itself besieged at Atlanta.

On July 17, 1864, Davis removed the cautious General Joseph E. Johnston from command of the Army of Tennessee and replaced him with Hood. The newly minted army commander was promoted to full general the next day. Hood inherited the formidable task of defending Atlanta against the three Union armies under Sherman at the gates of Atlanta. Davis passed over Hardee, a more conservative choice for command of the army, in the hope that Hood would win victories against Sherman’s grand army.

“He is eccentric, and I cannot guess his movements as I could those of Johnston, who was a sensible man and only did sensible things,” Sherman wrote of his new adversary. Hood counterattacked Union forces at Peachtree Creek on July 20, east of the city at Bald Hill in what was known as the Battle of Atlanta on July 22, and again at Jonesboro on August 31-September 1.

None of the three counterattacks loosened Sherman’s grip on the city. The upshot of three pitched battles in such a short period of time was that the Army of Tennessee suffered thousands of casualties that it could ill afford to lose. President Davis still retained Hood in command of the Army of Tennessee despite this disappointing performance and allowed him to proceed with his proposed offensive into Tennessee.

The Union high command had major concerns over Hood’s march north. However, Sherman had his own plans in mind. After securing Atlanta, he wanted to march through central Georgia to Savannah. Grant was reluctant to allow Sherman to leave if Hood’s army posed a threat to Union control of Tennesee.

“Do you not think it advisable, now that Hood has gone so far north, to entirely settle him before starting on your proposed campaign?” asked Grant. “With Hood’s army destroyed you can go where you please with impunity. If you can see the chance for destroying Hood’s army, attend to that first, and make your other move secondary.”

Hood may not have been a brilliant general, but Grant appreciated the damage he could inflict in Sherman’s absence. Sherman continued to press Grant to allow him to cut his supply lines and move south, focusing his attention on draining the resources of the South. Grant finally relented, but only under the condition that Sherman promised to leave behind enough troops to contend with Hood.

Thomas commanded the Union forces scattered across Tennessee. He requested that Sherman leave him with his old XIV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland, but Sherman insisted on retaining this veteran corps for himself. Sherman instead detached Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio to join Thomas in Tennesee. Schofield’s command comprised Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley’s IV Corps and Schofield’s own XXIII Corps.

Sherman also sent two cavalry divisions under the command of the youthful Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson to join Thomas. However, the horse soldiers were in poor condition and most needed to be remounted. In addition, the gruff but reliable Maj. Gen. Andrew J. “Whiskey” Smith was en route to Nashville from St. Louis with two strong divisions.

“If you can defend the line of the Tennessee in my absence of three months,” Sherman wrote to Thomas, “it is all I ask.” Sherman could not have selected a better man to handle the task ahead.

The 48-year-old Thomas was different from Hood in almost every regard. Thomas was cautious, methodical, and introverted. He was 15 years older than Hood. He ranked 12 out of 42 in West Point’s Class of 1840. After serving in the Seminole War and U.S.-Mexican War, Thomas served as an artillery instructor before being assigned to the U.S. Second Cavalry. Despite his Southern upbringing, Thomas remained a Union man, choosing his country over his friends and family. Thomas earned a reputation as one of the best generals in the western theater during the war, especially for his stand on Snodgrass Hill to cover the retreat of Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland at Chickamauga.

“General Thomas’ characteristics are much like those of my father,” wrote Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. “While I was under his command he placed confidence in me, and never changed it. Quiet, manly, almost stern in his deportment, an honest man, I trusted him.…” Many soldiers had the same sentiment as Howard, affectionately referring to Thomas as “Pap.”

After stubborn Union resistance at Decatur, Alabama, Hood’s army headed 40 miles to the west to Tuscumbia and crossed the Tennessee River at Florence on October 31. It crossed into Tennessee shortly afterward, heading northeast in the direction of Columbia. Hood was joined by Maj. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest’s cavalry corps. Including Forrest’s troopers, Hood had about 40,000 men divided into three other corps at his disposal, under the commands of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham, Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, and Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee.

The challenge that lay before Hood was to move rapidly by forced marches and destroy Thomas’s piecemeal forces before they could concentrate at Nashville. The first order of business was to destroy Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, which by November 22 was withdrawing north in good order to Columbia, Tennesee. Hood’s attempt to destroy the Army of the Ohio would be riddled with amateurish blunders and lost opportunities.

Hood’s first major misstep took place at Spring Hill on November 29. Although he overtook Schofield and ordered an attack that evening, his subordinate commanders called off the attack on the grounds that the troops were too exhausted to make a successful assault. That night, Schofield’s regiments snuck past Hood’s army and escaped to Franklin.

When Hood learned the next day what had occurred, he was furious that his orders to attack had not been followed. He laid most of the blame on Cheatham. Hood grumbled that he could have easily crushed Schofield with a single division. The failure to destroy Schofield at Spring Hill proved to be a travesty for Hood’s army. Many of his best men would die at Franklin and Nashville as a result.

Hood arrived on the heels of Schofield’s soldiers at Franklin on the afternoon of the next day. Schofield had to wait for pontoon bridges to arrive so that he could ford the Harpeth River to join Thomas at Nashville. He arrived that morning and had his men dig in while they waited for the bridges to arrive. Realizing that Schofield would easily reach Nashville once he crossed the river, Hood irrationally ordered an attack on the Union defenses with two of his corps. Hood suffered the loss of nearly 6,500 men killed or wounded during the ensuing assault.

“Just at daybreak, I rode upon the field and such a sight I never saw and can never expect to see again,” Cheatham recalled after the battle. “The dead were piled up like stacks of wheat and scattered about like sheaves of grain.… I never saw anything like that field, and never want to again.”

The Battle of Franklin decimated the officer roster of the Army of Tennessee. The most glaring loss was that of Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, who rightly was regarded as one of the best division commanders in the entire Confederate army.

In addition to Cleburne, Brig. Gens. John Adams, Hiram Granbury, States Rights Gist, and Otho Strahl also were killed in action that bloody day. A sixth general, Brig. Gen. John Carter, died in December 1864. Six other generals were wounded and one captured. Replacing them in time for future operations was extremely difficult given that 21 colonels and 11 lieutenant colonels were killed, wounded, or captured.

These losses had a devastating effect on the leadership of Hood’s army, drained it of needed manpower, and devastated its morale before it had reached Nashville. Franklin was “a great and uncalled-for disaster of the Confederate cause—a battle fought against great odds, without any compensating value if successful,” wrote Confederate Maj. Gen. Samuel G. French. Hood’s attack had gained nothing. Schofield’s men simply slipped away after midnight to join Thomas at Nashville.

Hood’s battered army continued its advance north to Nashville and arrived there on December 2. Even with the setbacks at Spring Hill and Franklin, Hood still planned to engage Thomas with his 30,000 men. Thousands of Rebels arrived at the outskirts of the heavily fortified city barefoot and without blankets. Hood planned to form a ring of trenches around Nashville two miles outside the Union fortifications “to await his [Thomas’s] attack, and if favored by success, to follow him into his works.” He clung to a sliver of hope that reinforcements would arrive in the form of Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s Trans-Mississippi Department to bolster his strength. Beauregard pleaded with Smith to assist Hood by sending two or more divisions to his aid. “The fate of the country may depend upon the result of Hood’s campaign in Tennessee,” Beauregard wrote to Smith. Smith did not send any troops.

Hood tried to encircle Nashville and trap Thomas inside the city’s works with his skeleton army. He positioned Lee’s corps of three divisions across the Franklin Pike in the center, Stewart’s Corps of three divisions on the left, and Cheatham’s corps of three divisions on the right. Neither of his flanks had enough troops to reach the banks of the Cumberland River. Stewart’s corps fell short by four miles and Cheatham’s corps by one mile. This left a five-mile gap in Hood’s encirclement, which failed to pin Thomas in Nashville. Hood’s poor deployment lessened any chance of success he might have.

Hood made another blunder by sending Maj. Gen. William B. Bate’s 1,600-man division to Murfreesboro, hoping that he could capture it and destroy bridges and blockhouses along the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. On December 4, Hood sent Forrest with two of his cavalry divisions under Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford and Brig. Gen. William H. Jackson to support Bate and assume overall command of the operation. Hood also added Colonel Jacob B. Biffle’s cavalry brigade from Brig. Gen. James Chalmers’ cavalry division and Colonel Charles H. Olmstead’s infantry brigade to Forrest’s command.

Hood dispatched Colonel David Coleman’s 700-man brigade of infantry and dismounted cavalry to join Colonel Edmund W. Rucker’s brigade in holding the four-mile gap between the Cumberland River on the extreme left flank of his army. The troop transfers left Chalmers with just 1,600 men to defend the key sector.

The Murfreesboro operation turned out to be a waste of resources and manpower when Forrest found the town held by 8,000 men under the command of Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau. Bate returned to Nashville after a Union sortie from the garrison defeated the Confederate force. Hood ordered Forrest to continue destroying the railroad around Murfreesboro with his two cavalry divisions. This removed one of Hood’s ablest subordinates and 5,000 men from the looming battle.

Hood was not the only one with problems; Thomas had his fair share, too. Thomas finally managed to gather his scattered units at Nashville thanks to Schofield delaying Hood. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio came up from Franklin and took up positions on Thomas’s right wing. Although their troops were tired from their flight from Hood for the past 10 days, they nevertheless were in good spirits. This force was bolstered by Maj. Gen. John B. Steedman’s Provisional Division. Steedman’s command was composed of various detachments from Tennessee and Georgia and two brigades of U.S. Colored Troops. In addition, Maj. Gen. Andrew Smith’s XVI Corps of two veteran divisions began arriving from St. Louis and unloaded at the docks at Nashville on November 30. Besides infantry, Thomas also had 7,800 cavalrymen of Wilson’s cavalry corps at his disposal.

Thomas intended for Wilson’s troopers to play a vital role in the upcoming operation, but he was still waiting for them to finish getting equipped and remounted. Lt. Gen. Grant, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and President Abraham Lincoln perceived Thomas’s delay to wait for his cavalry as apprehension. “This looks like the McClellan and Rosecrans strategy of do nothing and let the rebels raid the country,” Stanton telegraphed Grant. “The President wishes you to consider the matter.” Grant exchanged a series of wires with Thomas, urging him to attack Hood before he fortified or destroyed his railroads leading to Nashville.

Thomas assured Grant that he would move with all haste, but he needed to wait for Wilson first. This was not what Grant, Lincoln, or Stanton wanted to hear. “If he waits for Wilson to get ready, Gabriel will be blowing his last horn,” Stanton complained to Grant.

When his cavalry was finally ready for action, a freezing rain storm passed through Nashville, coating the roads in several inches of ice, further delaying Thomas’s advance. The temperature dropped to below zero. “I have the troops ready to make the attack on the enemy as soon as the sleet which now covers the ground has melted sufficiently, to enable the men to march,” Thomas wrote to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, Lincoln’s chief of staff. “As the whole country is now covered with a sheet of ice so hard and slippery, it is utterly impossible for troops to ascend the slopes, or even move over level ground in anything like order.”

Three days before the battle, Thomas invited his senior commanders to meet at his room at the St. Cloud Hotel in the city to discuss the weather conditions. Wilson, Smith, Wood, Steedman, and Schofield endorsed Thomas’s proposal to hold off the attack until the weather improved. Schofield admitted after the war that “the men could not have gotten round at all unless they had snow shoes or had their stockings outside their shoes.” Wilson claimed that the characteristically reserved Thomas confided to him his frustration over the continued pressure from his superiors. “The Washington authorities treat me as if I was a boy,” he allegedly told Wilson. “If they will just let me alone I will show them what we can do. I am sure my plan of operation is correct, and that we shall lick the enemy if he only stays to receive our attack.”

After more than a week of further delay, Grant was fed up with Thomas’s lack of action. He wired Halleck expressing his disapproval and recommended that Thomas be replaced with Schofield. “There is no better man to repel an attack than Thomas, but I fear he is too cautious to ever take the initiative.” On December 13, Grant ordered Maj. Gen. John A. Logan to go to Nashville and replace Thomas if he had not advanced by the time Logan arrived at the city. However, anxiety got the better of Grant, and he decided to depart from his headquarters at City Point, Virginia, the following day to go to Nashville and assume command. When he stopped in Washington, D.C., on his way to Nashville two days later, Grant learned that Thomas had launched his assault on Hood. Grant decided not to proceed any farther.

Steedman claimed after the war that there was a “Judas” among the senior generals who was trying to undermine Thomas. Steedman accused Schofield of betraying Thomas by wiring disparaging reports to the authorities in Washington. Schofield’s motive, Steedman alleged, was to get Thomas relieved of command so that he might succeed him. Schofield denied these accusations and called Steedman’s statement “false and slanderous.” Because of this matter, Thomas was nearly removed from command.

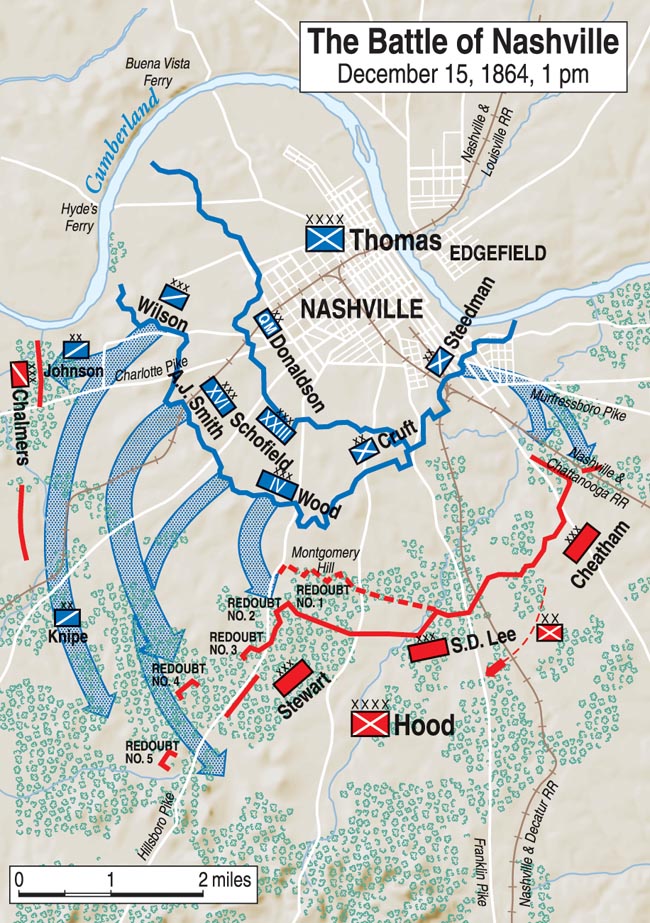

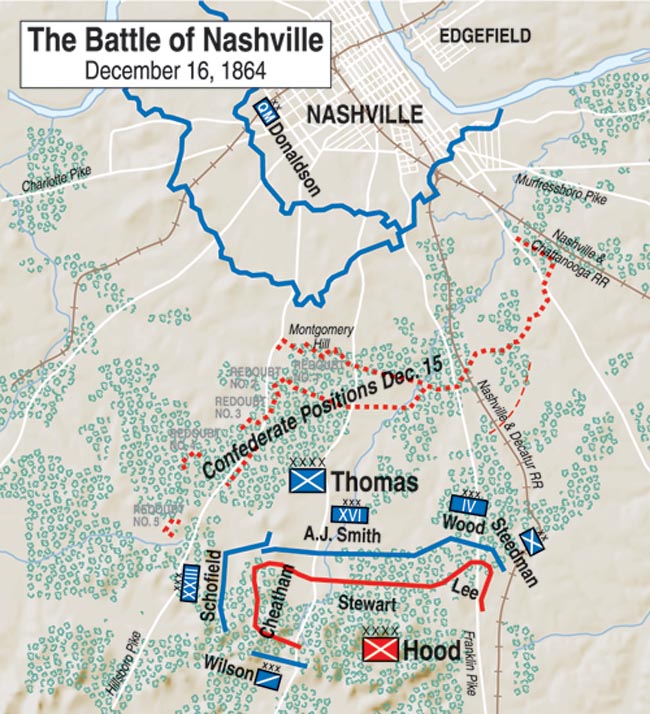

On December 14, the temperature rose and the ice finally melted, leaving the ground soft and slushy but the roads passable. Thomas called together his commanders that evening for a second meeting and laid out his plans to assault Hood’s army the following day. The hammer would fall from Smith’s XVI Corps, which would assault the enemy’s left flank from the Hardin Pike, supported by Wilson’s Cavalry Corps, which would swing around the Confederate flank. Wood’s IV Corps would form on the Hillsborough Pike on Smith’s left flank and concentrate to overrun the enemy position at Montgomery Hill. Schofield’s XXIII Corps would remain in reserve and support Wood’s attack. Steedman’s Provisional Detachment would make a heavy demonstration against the Confederate right flank to draw soldiers away from the main offensive on the left.

Brigadier General John F. Miller’s Nashville garrison and Brig. Gen. James L. Donaldson’s Quartermaster’s Division would be responsible for defending the city when Thomas’s men left the protection of the fortifications to attack Hood. At the last moment, Schofield reasoned that his troops should support Smith’s attack instead of Wood’s, and Thomas approved the change in plans. Thomas would have 55,000 men at his disposal for his attack.

At 6 AM the next day, Union troops began to move into position. Thomas checked out of his hotel room early that morning and made his way to a hill near the Hillsboro Pike to observe the battle. The weather was foggy and cold. At 8 am, Steedman initiated his attack on the Confederate right flank with 7,600 men in three brigades. They advanced along the Murfreesboro Turnpike targeting Granbury Lunette, named for one of brigadiers who fell at Franklin. Steedman’s brigades met heavy resistance and were badly cut up. During the brutal fighting, some of Colonel Thomas J. Morgan’s colored troops were trapped and slaughtered in a railroad cut. Hood began to send what reinforcements he could spare to his left, anticipating an attack on that part of his line.

Smith and Wilson, after a two-hour delay, moved their troops along Hardin Pike at 10 am to attack the flank of Stewart’s corps. Both commands wheeled east and headed toward the Confederate entrenchments running parallel to the Hillsborough Pike. Wilson gathered his brigade and division commanders the night before and stressed to them that their main objective would be to advance on the right of Smith’s infantrymen in order to overpower and turn the Confederate left flank. Most of his mounted regiments were armed with the fast-firing Spencer repeating rifles.

The weight of the Union attack was delivered by Smith’s corps, made up of Brig. Gen. McArthur’s 1st Division, Brig. Gen. Kenner Garrard’s 2nd Division, and Colonel Jonathan B. Moore’s 3rd Division. “At first was visible only a great silent sea of mist, making firm our path to distant hills where the rebels were entrenched and awaiting us,” wrote Chaplain Elijah Evan Edwards of the advance of McArthur’s division on the Confederate position. “Underneath this silent sea our army was creeping noiselessly, stealthily forward. The silence was dread, fearful, ominous for we know that it betokened coming thunderpeals.” As they came closer to the Confederate positions, they could clearly make out Confederate battle flags and gray columns and the roar of artillery from both sides.

Edwards and other soldiers were calmed by the presence of the division commander, Brig. Gen. McArthur, looking like a Highland chief in his tartan cap, and his staff, who wore matching caps, coolly directing the troops as they entered the fray.

Brigadier General Richard W. Johnson’s 2,600 cavalry troopers forced back Chalmers’ two brigades, which were outnumbered two to one, on the Charlotte Pike. They were supported by gunfire from Union gunboats on the Cumberland River. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Edward Hatch’s Fifth Cavalry Division and Brig. Gen. John T. Croxton’s 1st Brigade advanced along the right of Smith’s infantrymen and outflanked Stewart’s defensive position.

Redoubt No. 5 was the first to fall to the advancing Union cavalrymen. McArthur’s division, with the assistance of a brigade of Wilson’s cavalrymen fighting dismounted, stormed Redoubt No. 4. The rebels at that location held out valiantly against the overwhelming numbers for three hours. In the meantime, Colonel Sylvester G. Hill’s brigade of McArthur’s division captured Redoubt No. 3. Hill was killed in the desperate fighting.

Wood initiated his own attack. Brig. Gen. Washington Lafayette Elliott’s 2nd Division held the left, Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s 1st Division was in the center, and Brig. Gen. Samuel Beatty’s 3rd Division held the right. Their assault targeted heavily defended Montgomery Hill. It was spearheaded by Colonel P. Sidney Post’s 2nd Brigade of Beatty’s division. Schofield’s two divisions, Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch’s 2nd Division and Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox’s 3rd Division, came rushing up behind Smith’s command and pressed past his extreme right, adding extra weight to his attack.

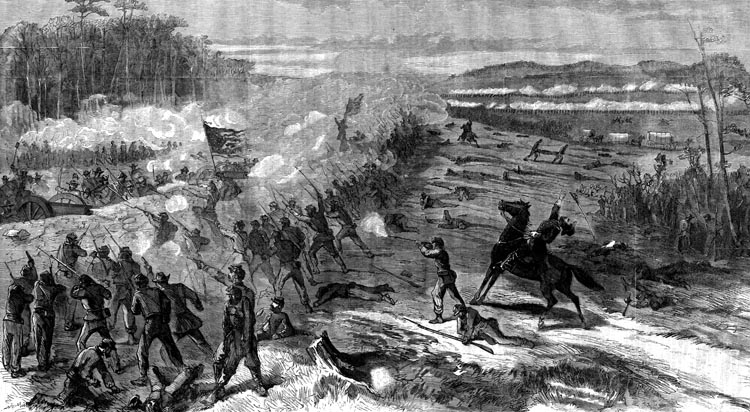

The combined effort from Wilson, Smith, Wood, and Schofield led to a collapse of the Confederate left flank and the capture of the last stronghold, Redoubt No. 1. “It was more like a scene in spectacular drama than a real incident in war,” recalled Captain Henry Stone, a member of Thomas’s staff. “As soon as the other divisions farther to the left saw and heard the doings on their right they did not wait for orders. Everywhere, by a common impulse, they charged the works in front, and carried them in a twinkling.… Everywhere the success was complete.”

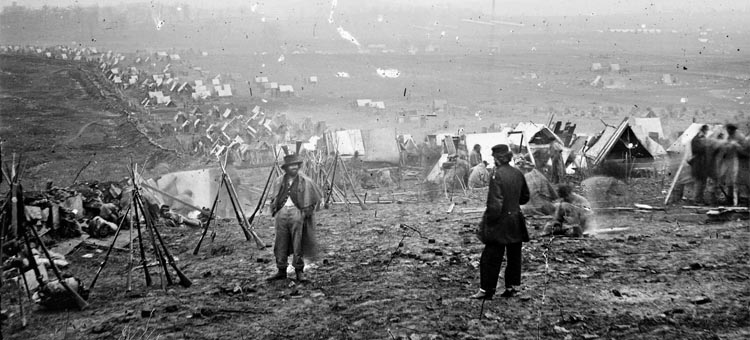

Thousands of men, material, and weapons fell into Union hands as Hood’s army retreated. Chaplain Edwards recounted the horror when he entered the captured Confederate entrenchments. “The sight in the rebel trenches is horrifying,” he said. “The dead and wounded lay there as they fell, pulseless, horribly mangled. The living gasping for water, or moaning their life away.”

Hood managed to consolidate and reform his routed army at a second defensive position to the south, anchored by Compton’s Hill on the left and Peach Orchard Hill on the right. Cheatham’s corps now held the left flank while Lee’s corps, which barely had been engaged in the battle, held the right. Stewart’s battered corps held the center. Thomas’s army pursued the Confederates and by nightfall was wrapped around the Confederate line like a double-ended fish hook. Schofield and Wilson formed the Union right, Smith in the center, and Wood, combined with Steedman’s command, on the left.

Lincoln telegraphed Thomas the next morning congratulating him on his victory but pressed him to continue with his success. “You made a magnificent beginning. A grand consummation is within your easy reach. Do not let it slip.” Lincoln could rest assured that Thomas did not intend to leave Hood alone. He planned to focus his attack on Hood’s left flank, as he did the previous day, to deliver the final blow. “I had hopes of gaining his rear and cutting off his retreat from Franklin,” he afterward reported. He wanted this to be the decisive battle in Tennessee.

At 6 am December 16, Wood’s and Steedman’s commands initiated the Union attack on the Confederate right flank but gained little. Smith’s divisions, sandwiched between Wood on his left and Schofield on his right, advanced on the Confederate center. Schofield’s infantrymen and Wilson’s dismounted cavalrymen struck the Confederate left. By noon, Wilson captured the Granny White Pike in the Confederate rear, cutting off one of their two lines of retreat to Franklin. A breakthrough came on Smith’s and Schofield’s sector, causing a complete collapse of the Confederate defenses. Thousands of Confederate soldiers fled down the Franklin Pike toward Franklin, pursued by Union soldiers and cavalrymen until nightfall.

Confederate Private Samuel R. Watkins described the frantic retreat of Hood’s army after the second day of the battle. Nearly every soldier threw away his guns and accouterments. Thousands of men were captured, while the rest kept moving despite being exhausted and hungry to avoid ending up in a Yankee prison. He saw large numbers of Confederate prisoners “broken down from sheer exhaustion, with despair and pity written on their features.” Wagons, artillery, cavalry, and infantry were jumbled together. Broken wagons, horses, and provisions littered the roadside.

Wounded in the middle finger and the thigh, Watkins unhitched a horse from an abandoned wagon and rode it back to Franklin. “My boot was full of blood, and my clothing saturated from it,” Watkins wrote. He observed a dejected Hood at his headquarters that night: “He was much agitated and affected, pulling his hair with one hand and [he had but one] and crying like his heart would break.”

Grant said after the war that he believed Hood’s strategy was unsound. “If Hood had been an enterprising commander, he would have given us a great deal of trouble,” Grant said after the war. “If I had been in Hood’s place I would never have gone near Nashville. I would have gone to Louisville, and on north until I came to Chicago…. If he had gone north, Thomas would have never caught him.”

Just five days after Thomas won the Battle of Nashville, Sherman departed Atlanta bound for Savannah, Georgia, at the head of 65,000 of his best troops, including most of his cavalry.

What remained of Hood’s defeated army continued its retreat for 100 miles until it crossed back into Alabama on December 26. Conservative figures estimate Hood’s loss at 6,000 men killed, wounded, and captured during the two-day battle at Nashville compared to Thomas’s 3,061 casualties. Hood lost approximately 60 percent of his army during the invasion of Tennesee. The crushing defeat ended any chance for Hood to foil Sherman’s March to the Sea or to dispute Grant’s campaign in Virginia. The defeated Confederate general resigned his commission in disgrace in January 1865. On March 3, 1865, Thomas and the soldiers under his command received the thanks of Congress “for their skill and dauntless courage” in driving Hood’s army from Tennessee. “His [Thomas’s] brilliant victory at Nashville was necessary to mine at Savannah to make a complete whole,” Sherman wrote afterward. Less than four months after the Confederate defeat at Nashville, Lee and Grant met at Appomattox Court House to negotiate the terms of the Confederacy’s surrender.