By Mark Simmons

“To cap it all, down came the fog, the sort you sometimes get at sea—one minute clear, the next in a fog bank—so we relied on our radar a lot. We carried on and suddenly the mist lifted and I saw them, and my heart stopped. They looked like the Houses of Parliament. Then they started firing their 11-inch guns against our 4-inch.”

—Dennis Bond, torpedoman, HMS Whitshed

Almost a year before these words were written, the old World War I-vintage V-and-W-class destroyer HMS Whitshed had encountered the German battle fleet in the English Channel. The enemy fleet’s main component—the two 32,000-ton battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau—had embarked in January 1941 on a cruise to attack British merchant shipping in the North Atlantic.

Within two months, the raiders had sunk 22 ships totaling almost 116,000 tons. Yet both ships were in need of repairs; Scharnhorst in particular had serious boiler problems. Thus, on March 22 both ships entered Brest on the northwest coast of occupied France.

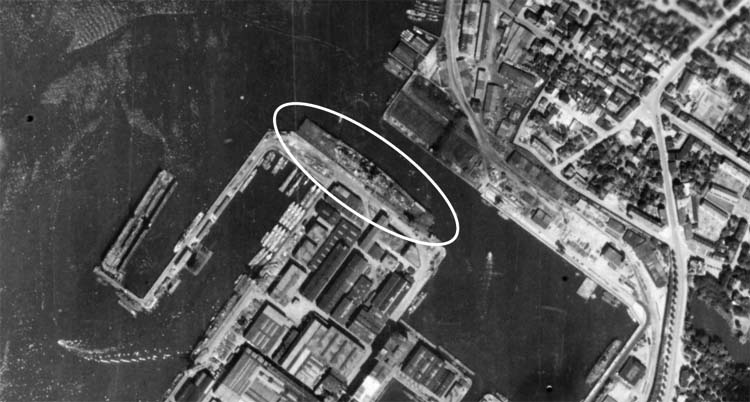

The former French naval base and dockyard with excellent facilities had been taken over by the Kriegsmarine in 1940. Work began immediately on the two ships, but their presence was soon discovered by the Royal Air Force and French Resistance. Ten days after they arrived, 109 Bomber Command aircraft attacked the harbor, dropping 132 tons of bombs. The ships were undamaged, although some of the ships’ companies living ashore were killed. The RAF continued its attacks over the next five days.

German engineers estimated it would take 10 weeks to repair Scharnhorst, while Gneisenau needed only minor work—work that was only entrusted to German dockyard personnel. On April 5 Gneisenau moved out of drydock to a sheltered mooring. It would prove an unlucky move.

Four Bristol Beaufort torpedo bombers were sent from St. Eval in Cornwall to attack the enemy ships. Three failed to find a target. But Flying Officer Kenneth Campbell, flying at only 50 feet above the sea, found Gneisenau moored close to the mole in Brest’s inner harbor. There were numerous antiaircraft batteries close by and three antiaircraft ships moored close to the battlecruiser, but in he went.

Part of the citation for Campbell’s Victoria Cross reads, “Even if the aircraft succeeded in penetrating these formidable defenses, it would be almost impossible, after delivering a low level attack, to avoid crashing into the rising ground beyond.”

Campbell’s torpedo hit the stern of Gneisenau, the explosion wrecking the starboard propeller shaft. After delivering his torpedo, Campbell had to make a steep banking turn, exposing his aircraft to heavy concentrated flak that brought the Beaufort crashing down into the harbor; Campbell and his three crewmembers were killed. The Germans buried all four men with full military honors.

The battlecruiser had to be pumped out to prevent it sinking. The next day it was back in drydock; inspections revealed Gneisenau would take six months to repair.

The RAF continued to raid Brest. On April 10, Gneisenau was hit again by bombs, resulting in more flooding. The Germans increased the port’s antiaircraft defenses, and more Luftwaffe fighter squadrons were deployed to the area.

On May 20, the battleship Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen sailed from Bergen, Norway, for the North Atlantic. Admiral Erich Raeder had hoped to send Bismarck and the two battlecruisers out against the convoy routes at the same time, but that was now impossible.

The British soon found the German ships, and on May 24 they confronted them with the battlecruiser Hood and battleship Prince of Wales. In the resulting exchange of fire, Hood blew up and sank, and Prince of Wales was damaged, although she managed to hit Bismarck and holed one of her forward oil fuel tanks. Prince of Wales and two cruisers continued to shadow the German ships.

Meanwhile, other British ships were closing in. Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers, nicknamed “Stringbags,” from the aircraft carrier Victorious, led by Lt. Cmdr. Eugene Esmonde, attacked Bismarck on the night of the 24th after a 120-mile flight in atrocious weather. One torpedo hit the battleship amidships with little effect. Esmonde was awarded the DSO for leading the flight.

Early the next day, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen parted company. Due to fuel loss and damage, the battleship was turning east for St. Nazaire while the cruiser would steer south. Bismarck then turned back against her pursuers. Fritz-Otto Busch on Prinz Eugen watched the battleship: “Gradually it became clear to the men assembled that they were seeing the flagship for the last time. Encircled by a halo from the salvoes of her own heavy turrets, militant and proud she disappeared, firing beyond the clear horizon.”

Over the next three days, Bismarck was attacked by more Stringbags, this time from the carrier Ark Royal, which slowed her down with a torpedo hit that jammed her rudders, making it difficult to maintain her course to the east. Two British battleships caught up with her and pounded her into a flaming wreck. The cruiser Dorsetshire finished her off with torpedoes; at 10:39 amon May 27, the mighty Bismarck sank.

Two days later, Prinz Eugen developed engine problems that could only be investigated properly in dock. Her captain skilfully avoided all the British ships and aircraft hunting her, and by June 1 she was close enough to France to be covered by German aircraft. At 3:59 pm, she anchored in the Brest roadstead and was quickly brought into the dockyard.

By the end of the month, the cruiser’s repairs were almost complete and she was hidden under extensive camouflage netting in a dock now filled with water. However, on July 1, an RAF raid hit the cruiser with an armor-piercing bomb. Busch recorded near misses with water spouting “mast high” and stones flying from the dockside striking the “mast and guard rail.”

When the damage reports came in, the forward control center was silent. It was soon revealed that a bomb had hit the port side of the ship below the bridge and penetrated the armored deck, exploding in the forward control compartment where the main armament was directed. Forty-seven of the crew were killed. It would take another three months to repair the ship.

By now Scharnhorst was almost ready for sea and went out on a short cruise to test all her systems and guns. The RAF spotted the movement and attacked the battlecruiser near La Pallice three times over a 24-hour period, hitting her several times. The ship began taking in water, but the crew was able to patch up the damage, and Scharnhorst limped back to Brest.

Hitler was becoming increasingly exasperated at the cost of maintaining the three ships in Brest for, as he saw it, dubious strategic reasons. He was also concerned that the British might try to invade Norway, so he reasoned the ships would be better deployed there. He ordered Raeder to draw up plans for the battle fleet at Brest to return to home waters.

Raeder tried to oppose Hitler, arguing the ships were better off at Brest to sortie out into the Atlantic; with Bismarck’s sister ship Tirpitz in Norway, they could sail out at the same time and really stretch the Royal Navy, which would have to disperse its capital ships to protect the convoys. If they returned to Germany, Raeder reasoned, it would be much easier for the British to bottle them up.

And the question was: how were they to return? The route via Iceland and through the North Sea was fraught with danger. To pass through the English Channel was lunacy, a suicide mission. But Hitler, characteristically, would not listen and ordered Raeder to get on with it. The naval planners vacillated, annoying Hitler, who finally made the decision on the Channel: surprise and a blanket of heavy air cover would see them through. It was left to Admiral Otto Ciliax, who commanded the ships at Brest, to come up with the operational details.

Ciliax’s plan called for the ships to leave Brest under the cover of darkness, but they would pass through the Straits of Dover in daylight. He warned that the air cover must be comprehensive or the fleet could face disaster. Hitler agreed to the plan and promised him the necessary aircraft to cover the fleet. He was confident it would work, doubting the British ability “to make lightning decisions” or to concentrate enough aircraft in southeast England.

Thanks to the Enigma codebreakers at Bletchley Park, the British were well aware of the situation the Germans faced. During the preparations for Operation Cerberus, as the maneuver was code named, the British knew that Scharnhorst’s gun crews, who had been aboard Prinz Eugen, were moving back to the flagship in preparation for sailing.

Although they evaded air reconnaissance, the capital ships, according to the decoded Enigma messages, were slipping their berths at night to give the crews some degree of training and checking systems and returning by dawn. Also, the concentration and increase of German fighter aircraft in northwest France was noted.

All this went to the Admiralty and Air Ministry although there was no direct mention of “Cerberus” or a mention of the “Channel.” The staff of the RAF and Royal Navy failed to pick up on this, however, so their advantage through decoded Enigma mesages know as Ultra was largely wasted.

The main concern of the Royal Navy was the threat posed to the Atlantic shipping by the German surface raiders. Thus, many of the Home Fleet’s heavy units were committed to convoy duties. The First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, was unwilling to commit his battleships to operations close to the enemy-controlled coastlines.

He was heavily influenced in this by the loss of Prince of Wales and Repulse off Malaya on December 10, 1941. However, it seemed to elude him (he was suffering ill health and in less than two years would die of a brain tumor) and his staff that these ships had been sunk by land-based Japanese naval aircraft highly trained in attacking ships and that the British ships had no air cover, whereas the Luftwaffe was never able to sink any British capital ships.

To have brought some heavy units to an east coast port within striking distance would have seemed the logical thing for the Royal Navy to do. However, the main role to prevent the German passage went to the light forces, motor torpedo boats (MTBs), destroyers, and minelayers, and attack from the air by torpedo bombers of the Fleet Air Arm and RAF Coastal Command and bombers from Bomber Command.

In Operation Fuller, it was expected that these forces would coordinate and overwhelm the German ships, but just how this was to be done with no joint command structure was a major flaw. They also assumed they would receive early warning of German movements.

This was partly based on the notion that the German ships would pass through the Dover narrows in darkness or just before dawn, which meant they would have to leave Brest in daylight. There, weather permitting—or so the thinking went—they would be spotted by standing air and sea patrols, giving the British time to assemble their forces.

The first alert line would be the seven submarines that had been patrolling off Brest and covering the Bay of Biscay since December 1941. These were old craft normally used for training; this soon had a detrimental effect on the supply of new submariners, so in January 1942 it was cut down to two submarines.

At night, RAF Coastal Command, flying Lockheed Hudsons, took up the main scouting role. These aircraft were equipped with shipping radar with a range of 30 miles. They flew patrols over three lines: “Stopper,” from Brest to Ushant; “Line South East,” from Ushant to Brehat; and “Habo,” from Le Havre to Boulogne. In daylight, Fighter Command would take over the “Habo” patrol.

Also, there was a string of radar stations along the south coast of England with longer range radar that could pick up shipping in the Channel—even close to the French coast.

The Germans brought in considerable forces to escort the three heavy ships. Close escort would be provided by the 5th Destroyer Flotilla. There were also three flotillas of E-boats—fast motor torpedo boats. These, in turn, would meet the fleet as it moved north from their bases at Cherbourg, Le Havre, and Cap Gris Nez.

Operation Thunderbolt was the code name of the Luftwaffe task to supply air cover for the German battle fleet in the Channel and on into the North Sea; Maj. Gen. Adolf Galland, the celebrated air ace, was given command of the operation. In January he had been awarded the swords and diamonds to his Knights Cross by Hitler. Galland was given a free hand. Later he would admit that this was because other more senior commanders thought it would end in disaster and were distancing themselves from the operation.

Galland would have 252 aircraft—mainly Me-109s and FW-190s—under his command, plus a further 30 Me-110s for patrols. During daylight hours it was planned to have 16 fighters over the fleet continually. They would be there for 35 minutes, while relief patrols would engage 10 minutes before the previous patrol was due to leave, so for 20 minutes in every 70, a total of 32 aircraft would be over the ships.

To achieve this, ground crews had to turn the fighters around in no more than 30 minutes. Galland set up four sectors—JA covered Cherbourg and Le Havre; Sector 1 covered the area south of Abbeville to just north of Dunkirk; Sector II covered the Belgian and Dutch coasts up to the Rhine; and Sector III spanned from Amsterdam back to Wilhelmshaven. He also placed handpicked airmen on each of the capital ships through whom he could communicate.

On January 4, the Admiralty warned that Scharnhorst and Prinz Eugen would be ready to sail from Brest by the 24th and Gneisenau by early February. Their destination could be the Atlantic, the Channel, or even the Mediterranean. If the latter, the RAF’s Force H at Gibraltar would be ready.

Another worry for the Royal Navy was a large troop convoy due to leave for Africa on February 14. It already had the old battleship Malaya as escort, but the battleship Rodney was ordered from Gibraltar to assist. On February 5, the modern submarine Sealion was sent to reinforce the Royal Navy patrol off Brest.

On February 11, Admiral Ciliax called his senior officers together on the flagship Scharnhorst to tell them they would set off that night. All was ready: escorts and fighter cover were on alert, and minefields had been swept. They would leave harbor at 7:30 pmas they had been doing for several days during working-up exercises. That night, just as they were casting off, the RAF turned up on a bombing raid. Ciliax cancelled the sailing and waited; 90 minutes later the bombers had gone and again he ordered the cast off. Clear of the breakwater, the destroyers took station; Scharnhorst led, followed by Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen. It was 9:30 pm.

The submarine Sealion was near the Whistle Buoy that night, five miles from Brest harbor, waiting on the surface. Lt. Cmdr. George R. Colvin had tried the same tactic the night before but had been forced under by patrol boats that depth charged him. The conning-tower party soon heard the drone of bombers overhead making for Brest. The black sky was soon lit up by the flashes of explosions. Bomber Command had arrived. An hour later, Sealion withdrew to charge her batteries. Britain’s first patrol line had gone. The other two submarines were 40 miles to the south.

A Hudson patrol aircraft from 224 Squadron took off from St. Eval at 6:27 pm,but during an encounter with a Ju-88 the pilot had to take evasive action. He ordered the radar switched off to reduce the light being shown. As soon as he had shaken off the enemy plane, the navigator switched the set back on, but it was dead. He advised flight control that they were returning to base at about 7:30 pm. St. Eval had failed to pick up the message until the aircraft was 10 minutes from base.

On arrival, the crew changed to a spare Hudson but were not back on patrol until 10:40 pm, by which time the German ships had passed through the “stopper line” undetected. A second Hudson had taken off not long after the first patrol to take up its sweep over the Line South East, arriving over the area at 7:36 pm. A few minutes later, that aircraft’s radar also failed. After reporting the problem, the aircraft broke off the patrol at 9:39 pmand returned to base. At that time the German ships were leaving Brest.

Around midnight, Ciliax’s ships were off Ushant, making 27 knots, and had already made up some of the lost time due to the air raid at Brest. Fritz-Otto Busch aboard Prinz Eugen said the night was black and the destroyers and E-boats were in position. “Now and again their shadows could be seen gliding past like ghosts. There was not much to be seen of the battleships; they were sailing on ahead, swallowed by the darkness which lay somberly upon the sea.”

The crew was closed up to “action stations” with antiaircraft guns manned. By 5 amthe ships were passing the German-occupied Channel Islands and were nearing the English Channel proper. Then there would no way back. The next stop must be home waters.

The first British “Habo” patrol, with the Hudson from 223 Squadron, had set off a half hour after midnight from Thorney Island near Portsmouth. Its route—Boulogne to Le Havre and the mouth of the Seine River—shadowed the French coast 12 miles out. It took two hours to complete two circuits. Nothing was seen, so at 3:55 pmit returned to base. A second Hudson was in position by 4:30; it covered the same route twice and returned to base at 7:15 am, having seen nothing. By then the German fleet was northeast of Cherbourg—the area the Hudson had flown over an hour earlier.

Dawn broke at about 7:45 amas signal lamps flashed between the German ships. Five minutes later, right on time, coming in from astern roared Galland’s fighters dropping recognition flares. They then climbed to operational altitude, where they began flying a circular pattern over the fleet.

At 8:35 am, at his Dover headquarters, Admiral Bertram Ramsay, as nothing had been reported, ordered his units to stand down to four hours readiness until the next night.

At 8:45 am, two Spitfires of No. 91 Squadron at Hawkinge took off to cover the “Habo Line” and beyond—from Le Havre to Cap Gris Nez. The Spitfire on the northerly leg saw nothing. The other one saw some E-boats leaving Boulogne heading southwest but nothing else and at 9:04 turned for home. Without realizing it, that pilot had seen E-boats going to join the battle fleet; a little farther to the southwest he would have spotted the German ships.

The radar station at Beachy Head changed shifts at 8 am. The fresh operators became suspicious as there seemed to be enemy aircraft flying in circles off the French coast. They reported this to Fighter Command. An hour later, they were blind again with interference. Galland and Luftwaffe General Wolfgang Martini had devised a primitive form of radar jamming that appeared on the receiving set as atmospheric interference. This was coupled that morning with two Heinkel He-111s flying parallel to the English coast with radar distortion equipment that gave false echoes to the British radar stations.

An hour later, the interference cleared again and it seemed there were ships on the plot below the aircraft. They plotted the range as 44-46 miles. The station passed this information to RN Dover Command. By now, other stations were picking up and reporting the circling aircraft. Squadron Leader Davis at Fighter Command HQ Uxbridge took it higher to Air Commodore Ernest Norton; it was decided more than likely to be a German air-sea rescue operation.

Davis was far from satisfied as reports continued to come in picking up large vessels with an air umbrella over them moving northeast at 30 knots. At 10:10 am, he ordered No. 11 Group to send another flight over the area; that flight was in the air 10 minutes later. By now the weather had closed in, but seven miles off Boulogne they spotted nine E-boats in two lines. The British pilots followed them and located a great number of ships.

Unknown to them, another flight of two Spitfires from RAF Kenley, piloted by Group Captain Victor Beamish and Wing Commander Boyd, were out on a training flight “keeping their hands in” over the same area. They almost bumped into the two aircraft from Hawkinge.

Beamish described what they came across: “We were about five miles off the French coast near Le Touquet. I saw two ships roughly in line astern, surrounded by about 12 destroyers, circled again by an outer ring of E-boats. When we arrived over the ships, we saw in the air around nine to 12 Me-109s. They immediately attacked us.”

Beamish and Boyd both took evasive action, turning away sharply, which drew antiaircraft fire from the ships below. However, both pilots managed to open fire on the E-boats before diving into cloud cover. This was the first action taken against the German fleet since it left Brest.

The planes raced home in complete radio silence. They were obeying RAF standing orders but in doing so lost a valuable half hour. In a later report, the RAF argued the pilots had done the right thing as the “object of the fighter is to get the report back to headquarters without the enemy realizing they had been seen.” But in this case they had been seen and this would not have altered the German objective. Radio silence, therefore, should have been broken. Operation Fuller was at last activated.

Ramsay had two weapons systems equipped with torpedoes that could be sent against the enemy relatively quickly, MTBs at Dover and Ramsgate and the slow Swordfish torpedo bombers based at Manston. None of the RAF Beaufort torpedo bombers were in position; they had to get to Kent first. Ramsay had little choice but to strike with what he had, although both options were better suited to night actions. At one point there had been 32 MTBs allotted to the task, but only a few days before many had been stood down as the Admiralty felt the crisis had passed.

The old shore batteries at Dover engaged the German ships at 12:19 pm, but only the four 9.2-inch guns at South Foreland had the effective range. They continued firing until 12:36 pm, but no shot fell within a mile of the enemy. The gunnery commander on Prinz Eugen was heard to remark, “Well, that wasn’t much, was it?”

Lieutenant Commander Edward Pumphrey, head of a motor torpedo boat squadron, got the call from headquarters high in the cliffs: “The battlecruisers are out; how soon can you be ready for sea?” Within 25 minutes Pumphrey, in MTB 221, was leading his five serviceable craft out to sea, working up to 36 knots. Two MGBs (motor gun boats) were supposed to accompany the MTBs, but their commanders were ashore. Pumphrey left orders for them to catch up as soon as they could.

At 12:23, he reported “Enemy in sight.” With the range down to about 1,000 yards from the E-boat screen, the MTBs opened fire. The flotilla had spread out; the MTBs were now about 5,000 yards from the capital ships. Ideally they needed to be within 2,000 yards of their target before firing the torpedoes.

At this point Pumphrey’s boat developed engine trouble and started dropping behind, but he signalled the others to continue the attack. He fired his torpedoes in the general direction of the leading battlecruiser, hoping they would hit something.

The MTBs tried to break through the E-boat screen, which brought them under intensive fire. Unengaged German fighters dropped down to sea level to strafe the boats. Trying to attack independently, most MTBs released their torpedoes at a similar long range to Pumphrey’s. MTB 44, commanded by Lieutenant Saunders, an Australian, had also suffered engine problems and dropped astern. He cleared the trouble and in the confusion got inside the E-boat screen, firing his torpedoes at about 3,000 yards at Prinz Eugen. A large spout of water was seen to rise from the cruiser. Saunders thought it might have been a hit, but this was not the case.

Three more MTBs from Ramsgate, under Lieutenant Long, started out at 12:25 but they failed to make contact with the enemy’s heavy units, only coming across the tail end E-boats of the fleet disappearing to the northeast in misty weather.

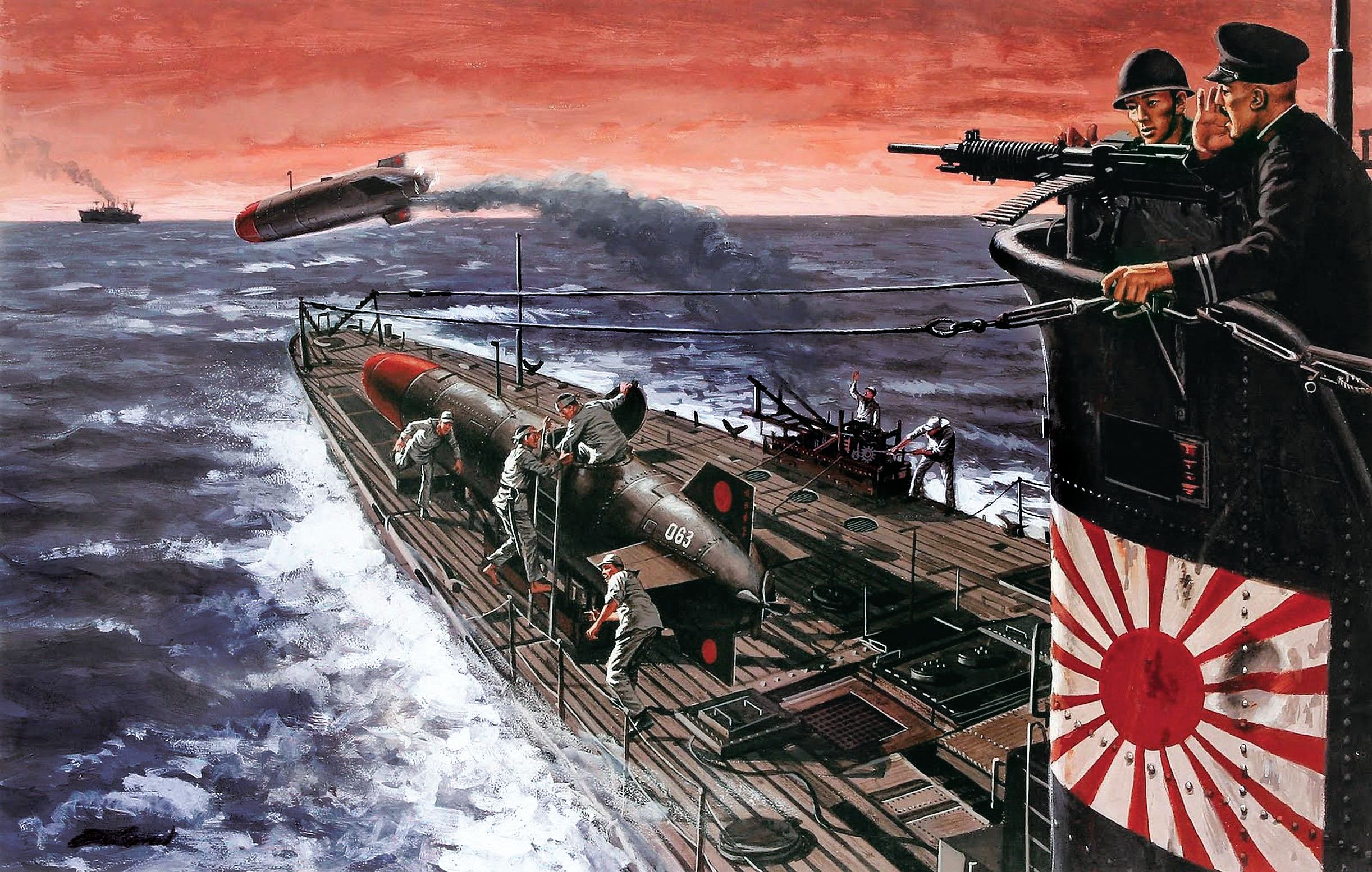

During the attack by the Dover MTBs, the German defenders on the ships and in the air were distracted by the arrival of Swordfish from the 825 Squadron Fleet Air Arm, based at RAF Manston in Kent and covering Spitfires at 12:50.

This squadron had performed well in the Bismarck chase; Eugene Esmonde, its commander, had been awarded the DSO for his leadership in finding the battleship in heavy weather. However, 825 Squadron was now understrength with only six aircraft, and in the Fuller plan the Swordfish, like the MTBs, were expected to attack at night.

The Swordfish, although an outdated, slow biplane, was an excellent, stable aircraft for the torpedo-bomber role and could endure heavy punishment. Believing the Stringbags had little chance of success, Admiral Ramsay contacted Pound asking to stand 825 Squadron down, but the First Sea Lord would not countenance not attacking the enemy “whenever and wherever he is to be found.”

Ramsay was still not happy, although he gave the order for 825 to attack. He asked the RAF liaison officer, Group Captain Constable-Roberts, to advise Esmonde that the final decision was his. This did not really help, putting Esmonde in an impossible position. He came from a southern Irish family and his father had espoused the nationalist cause before the creation of the Irish Republic. Yet, an earlier relative, Colonel Thomas Esmonde, had been one of the first recipients of the Victoria Cross for his actions in the Crimean War, and Eugene’s half brother Geoffrey had died at Ypres serving in the British Army in World War I. Honor and duty were strong traditions in the family, and he was well aware his aircrews were on a suicide mission, but he did what was expected of him and asked Constable-Roberts to let Ramsay know the attack would be made.

At the same time, Fighter Command was trying to scramble its squadrons to support the MTBs and the Swordfish. No. 11 Group was ordered to provide cover for 825 Squadron and contacted Esmonde direct by telephone, outlining their plan to send three squadrons to Manston that would rendezvous with the Swordfish that were due to set off at 12:25 pm. Two further squadrons of Spitfires were coming from Hornchurch to provide close support. With so many fighters in support, 825 might stand something of a chance against the German fleet’s antiaircraft guns.

However, the plan soon began to unravel as the first fighters to arrive were seven minutes late and they had flown from Gravesend, the nearest fighter base to Manston. Esmonde waited until 12:34, but no more fighters had turned up. With the enemy off Calais maintaining 30 knots, he could wait no longer. The fighters would have to catch up.

Two squadrons from Biggin Hill arrived at 12:36, but finding nothing waiting over Manston, they set off to the northeast and soon began tangling with enemy fighters. The two squadrons from Hornchurch failed to find the enemy fleet and were soon engaged by the Luftwaffe.

Galland had managed to increase the fighter cover for the ships as the fleet got closer to the Luftwaffe airfields. There were now 40 Me-109s on duty. As 825 approached, they only had 10 Spitfires with them instead of the expected 50 but gamely tried to drive off the enemy.

The first flight of three Swordfish in arrowhead formation was led in by Esmonde. Flying at a steady 80 knots, he crossed the destroyer screen through a hail of antiaircraft fire, but his aircraft began trailing smoke. He picked out Scharnhorst as his target.

The battlecruiser’s main 11-inch guns opened up, laying a thick carpet barrage ahead of the Swordfish, but like a charging cavalryman Esmonde flew straight on through. The aircraft was hit again, wounding Esmonde. The port lower wing was shot away, and the aircraft started to wobble as he wrestled with the controls. His two crewmen were already dead. Reports vary, but it must have been under 2,000 yards that he released his torpedo. Moments later the Swordfish crashed into the sea.

The observer in the Swordfish that followed Esmonde, Sub-Lieutenant Edgar Lee, was shouting at brian Rose, his wounded pilot, to “keep the nose up” as the aircraft was leaking fuel from a damaged tank. A thousand yards out, Rose released the torpedo. As they turned away, Lee saw his torpedo bounce on the water and head for Prinz Eugen.

Sub-Lieutenant Kingsmill’s Swordfish, third in the flight, had taken tremendous punishment. His engine had been blown apart and he and his two crewmen were wounded. Yet, he kept the nose up and released his torpedo at 2,000 yards, again at Prinz Eugen. The crippled Swordfish then seemed to give up and flopped into the sea. Although wounded, all three men managed to escape before the aircraft sank. It was a miracle that of the nine men in the first flight five survived.

Of the five survivors, only Edgar Lee was in any condition to make a report. After seeing him, Admiral Ramsay signaled the Admiralty, “In my opinion the gallant sortie of these six Swordfish constitutes one of the finest exhibitions of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty that the war has yet witnessed.”

The fate of the second flight led by Lieutenant Thompson is not as well known, as none survived to give their reports. Some of the Spitfire pilots and MTB crews bore witness to the determination in their attack, flying through a wall of heavy flak barely 50 feet above the waves.

The Luftwaffe battle diary for that day paid tribute to the Fleet Air Arm Swordfish that were “piloted by men whose bravery surpasses any other action by either side that day.”

The role of Bomber and Coastal Commands was marked by incompetence and, from the former, little idea of attacking ships at sea. The Beauforts of Coastal Command had been warned that the Germans were likely to try and force the Channel after February 10.

In view of this, Air Chief Marshal Philip Joubert ordered the Beaufort squadrons to move to airfields closer to the Channel. This concerned two squadrons, 42 at Leuchars in Scotland and 86 at St. Eval in Cornwall. A third squadron, 217, was already at Thorney Island.

The seven Beauforts at Thorney Island were ordered to rendezvous with fighter cover over Manston at 1:30 pm, but from the start things began to go wrong. The force was soon down to four aircraft as two had been armed with bombs by mistake and one had broken down. The four aircraft set off for Manston late, while the two remaining had the bombs changed to torpedoes and would make their way independently.

Finding no Beauforts waiting for them over Manston, the fighters carried on into the Channel. When 217 arrived, they began circling and waiting for the fighters. Confusion reigned until at last they set off alone. Eventually two aircraft found the target. At 3:45 pmthey attacked through heavy flak, but no hits were made.

The Beauforts in Scotland were there to cover the Tirpitz should she sortie from Norway. They were ordered south to Coltishall in East Anglia, but bad weather delayed their departure until February 12, when the German ships were already in the Channel. They left at 9 amwith 14 aircraft; one was lost over the Humber.

Upon arrival at Coltishall, it was found that three had no torpedoes and there were none at the airfield. The Beauforts were supposed to rendezvous with some Hudson bombers and fighters over Manston at 2:50 pm,but by that time the battlecruisers were well clear of the narrows. For once all the aircraft arrived on time, but during the flight out over the sea cohesion was lost due to bad visibility, and the aircraft had to make their own way. Six of the Beauforts managed to attack Gneisenau but recorded no hits. The Hudsons, using their radar, found the enemy earlier and pressed home their attack, but two were shot down.

From St. Eval, 12 Beauforts of 86 Squadron arrived at 2:15 pm at Thorney Island, where they refuelled. They were then ordered to fly onto Coltishall to meet their fighter escort and head out to the Dutch coast, where the enemy ships were expected at about 5:45 pm. Again, all went awry; no fighters turned up. As the light was fading, Wing Commander Flood decided to carry on alone. They failed to find the enemy ships even when dispersed; two aircraft failed to return.

During the disjointed Beaufort attacks and attempts to find the enemy, at 2:30 pmScharnhorst fell afoul of the one effective British weapon in Operation Fuller. Leaving the narrows, the german ships had increased speed, but off the mouth of the River Scheldt Scharnhorst shuddered as the violent explosion of a mine shook her and the engines were suddenly silent.

Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen, moving to port, passed the stricken flagship, thus obeying the operational orders to keep going even if one of their number was damaged. The RAF and the fast minelayer Welshman had been hard at work sowing mines faster than the German minesweepers could clear them.

Scharnhorst was dead in the water, holed on the starboard side with two compartments flooded. Admiral Ciliax, hearing the damage reports, immediately ordered the destroyer Z-29 to take him off, as he could not control the operation from a damaged ship; four torpedo boats remained behind to render assistance to the battlecruiser. Chief Engineer Kretschmer and his men set to work to get the ship, which was then a sitting duck, moving again. Luckily, no RAF bombers found her. By 2:50 pm, steam was being raised, and 10 minutes later she was underway again, soon building her speed up to 27 knots and chasing the fleet.

Bomber Command had some 100 aircraft, mostly Vickers Wellington and Bristol Blenheim bombers, on four hours’ notice. They arrived over the enemy fleet about the time Scharnhorst hit the mine. But clouds were obscuring the targets; they had to come down to sea level to find anything. None of the returning aircraft claimed to have found the enemy, but five aircraft were lost—likely flying too low and crashing into the sea.

A second wave of 100 aircraft fared no better; nine aircraft were lost over the target area at 4:30 pm. A third wave of 41 mostly four-engine heavy bombers failed again to find anything, and one aircraft was lost. The attacks by Bomber Command achieved nothing and underlined the ineffectiveness of high-level bombers in anything but ideal conditions.

Sending the aircraft out in low cloud when the armor-piercing bombs they carried needed to be dropped from 7,000 feet to be effective is questionable in view of the 17 aircraft lost. Even the Bomber Command view that they might “distract the enemy” for the torpedo bombers and destroyers is hardly credible.

The destroyers of the Harwich-based 21st Flotilla, under Captain Charles Pizey of the Campbell, received the news at 11:56 amfrom Dover that the enemy ships were in the Channel. They had already been stood down and were dispersed, carrying out independent exercises.

Pizey signalled his ships to gather near Buoy 53 of Harwich; by 1:18 pm, all ships were closed up as they increased speed to 28 knots. It was clear by now the destroyers could not cut the enemy off by heading southeast, so Pizey’s only option was to head east to catch them somewhere near the River Mass. The only drawback to this plan was a minefield that lay across the route; he decided to discount this and sail through the mines. Not long after the increase in speed, Walpole’s engines began giving trouble and forced the ship to drop out of line.

Dennis Bond and his shipmates onboard Whitshed worked on their skills with the torpedo tubes: “We did several exercises to see how fast we could turn the tubes from port to starboard.” The torpedomen were then ordered to strap themselves to the tubes. They would soon find out why.

Campbell’s radar picked up the enemy ships at 9.5 miles, passing from right to left across their course. Mist and rain had cut visibility at sea level to four miles. Pizey planned to try and get some leeway on the enemy before turning to starboard to launch torpedoes. The attack would be made in two divisions: Campbell, Vivacious, and Worcester in the first with Mackay and Whitshed in the second.

As they closed on the enemy, they spotted several aircraft flying low: Beauforts and Wellingtons and Me-109s and Ju-88s. Some of the British aircraft tried to bomb them. They could now see the enemy’s gun flashes. The destroyers turned to attack. They had been spotted. Pizey ordered his ships to zigzag as the enemy guns found the range. The destroyers replied with their 4-inch guns.

As Whitshed heeled over at full speed, Dennis Bond said, “The racing water came up to my knees, and I knew what the lashings were for. Without them we would have been washed away.”

Pizey described the attack: “At 3,500 yards I felt our luck could not hold much longer. Ships were being straddled and we were closing fast, gradually losing our bearing. At 3,300 yards I saw a large shell which failed to explode or ricochet, dive under the ship like a porpoise and I felt this was the time to turn and fire our torpedoes.”

Campbell and Vivacious launched their torpedoes about the same time and turned away. Worcester, lagging behind, fired her torpedoes at about 4,000 yards. By then the enemy ships were taking evasive action and turning away. All the torpedoes missed.

Up to this point, the three destroyers had ridden their luck; other than shell splinters striking the ships, they had suffered no heavy damage. However, as Worcester began to turn away she was struck by a salvo of heavy shells that damaged the boiler room. As she came to a stop and took a heavy pounding, the ship began flooding. The captain gave orders to prepare to abandon ship. Worcester was left on fire as the German fleet continued on its way.

Campbell and Vivacious soon found the stricken Worcester; the wounded were taken off and fires brought under control. Pizey offered to take her in tow, but by now Worcester, her boilers back on line, began to limp along. The rest of the flotilla was ordered back to Harwich at all speed to rearm the torpedo tubes in case another opportunity should present itself. Worcester made her own way back, at times reduced to three knots. She arrived back in Harwich the next day.

Enemy attention now switched to the approaching Mackay and Whitshed, which were surging toward Prinz Eugen. They both fired their torpedoes between 4,000 and 3,000 yards, and all torpedoes were seen to be running. Fate was kind to the two German ships as they turned toward a bank of mist.

The 21st Flotilla had pressed home its attack with great dash and courage but was totally inadequate for the task it had been given.

Having taken evasive action during the destroyer attack, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen lost contact with each other in the poor visibility. Z-29, with Admiral Ciliax on board, broke down when a shell misfire ruptured an oil line. Ciliax transferred his flag to the destroyer Hermann Schoemann. He was on board at 6:16 pmwhen Scharnhorst, looming out of the mist, almost hit the destroyer. The fleet was now spread over several miles around the Frisian Islands, preparing to turn northeast around the coast of Holland and then home. But itvwas not yet out of danger.

At 7:55 pm, off the island of Terschelling, Gneisenau was rocked by an exploding mine; the ship had a gaping hole on her starboard side. She came to a stop as engineers surveyed the damage; within 30 minutes, after some makeshift repairs, she was underway again. At 9:35, Scharnhorst, still some way off the same island, struck her second mine. This time it was more serious, and she took in thousands of tons of water. One engine was badly damaged, and electrical power was gone. She was dead in the water unable even to operate her guns.

However, Scharnhorst did have the genius of Chief Engineer Kretschmer and his men. After 35 minutes, he reported to Kapitan Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann that he had one screw operating and enough power to make 14 knots. Electrical power was restored by 10:15 pm,and the ship was moving again.

By dawn on February 13, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen had made contact off the port of Brunsbuttel. Shockingly, there were no tugs waiting to assist them. Approaching the port, Gneisenau hit a submerged wreck, causing more damage to the wounds the mine had already inflicted. Scharnhorst limped into Wilhelmshaven later that morning.

The Channel Dash had cost the Germans 17 aircraft shot down, while the Luftwaffe lost 11 men and the Kriegsmarine two. Additionally, two torpedo boats were damaged, and the two battlecruisers had suffered damage below the waterline.

But the Nazis were quick to take advantage of the remarkable victory, their propaganda machine going into overdrive. Hitler basked in the glory of being proved right. Admiral Ciliax and Kapitan Hoffmann each received the Knights Cross.

In Britain, there was a national outcry at the perceived incompetence. The Times lambasted the inept performance of the armed forces, saying that Admiral Ciliax had “succeeded where the Duke of Medina-Sidonia failed.” The duke had commanded the Spanish Armada in 1588. “Nothing more mortifying to the pride of our sea power had happened since the seventeenth century.”

This embarrassment was quickly followed on February 15 when Singapore fell and Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his government came under scathing attack from all sides. Against his better judgment, Churchill ordered an inquiry into what became known as The Battle of the Narrow Seas, which he considered of “minor importance.” The findings of the inquiry were handed into the prime minister in early March, but for security reasons they were not published until after the war.

The Bucknell Report, named after the president of the three-man board of inquiry, was released in 1946. It concluded, “Apart from the weakness of our forces, the main reason for our failure to do more damage to the enemy was the fact that his presence was not detected earlier, and this again was due to the breakdown of night patrols and omission to send out a strong morning reconnaissance.”

The blame was laid squarely on the RAF. Yet the Admiralty’s reluctance to move a capital ship nearer to the action was a complete misreading of the abilities of air power. The battleships Rodney or King George V and some cruisers within striking distance might have made all the difference.

Bitter recriminations continued in some cases for years between some of the commanders. Although Admiral Ramsay blamed himself for not anticipating German moves better, he turned his venom on Fighter Command for not supporting Esmonde properly and Coastal Command’s failure to sight the enemy. No mention was made of Ramsay’s report in the inquiry; it was likely suppressed in the interests of unity.

Home waters proved no safe haven for the German ships, however. Ten days later, off Norway, Prinz Eugen was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Trident; hit in the stern, she limped back to port and was out of action for months. Later in the war, she did take part in actions against Russian forces as they advanced into East Prussia.

At the end of February 1942, the RAF bombed Gneisenau on three consecutive nights. She was badly damaged and never went to sea again; she finally was used as a block ship and her heavy guns removed for coastal defenses. Scharnhorst did fight again but was sunk on December 26, 1943, in the Battle of the North Cape off Norway by the British Home Fleet, after she had tried to attack convoys bound for Russia. Out of her crew of 1,970 only 36 survived.

In the end, the “Channel Dash” proved a setback for the German Navy and relieved the Royal Navy of the necessity of covering Brest. Admiral Raeder considered the affair “a tactical success but a strategic defeat.”

What of the men? King George VI awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously to Eugene Esmonde. The citation began, “Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde knew well his enterprise was desperate….” He had “serenely challenged hopeless odds” and ended: “His high courage and splendid resolution will live in the tradition of the Royal Navy and remain for many generations a fine and stirring memory.”

Eugene’s invalid mother Eiley, his brothers, and sister went to Buckingham Palace. There the monarch presented the elderly lady in a wheelchair with the medal. The king expressed his sorrow at the death of her son and recalled that only recently he had invested him with the DSO. Esmonde had said of the DSO on that occasion that it was for all those who had attacked the Bismarck in May 1941. His posthumous VC was surely in recognition for all those who had tried to stop the German fleet in February 1942 and paid with their lives.

The story of Eugene Esmonde did not end there. As if wanting to bring some succor to the grieving family, the sea returned his body. It washed ashore in the Thames Estuary on the Kent coast on April 30, 1942. The dead man wore the uniform of a lieutenant commander in the Royal Navy; his body had been kept afloat by a semi-inflated life belt. He wore an identifying signet ring on the little finger of his right hand. The body was taken to Chatham, where it was soon positively identified. He had suffered grievous wounds down his back from neck to waist. His remains were buried at Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham, Kent.

On May 13, 1945, Winston Churchill broadcast his famous “Five Years of War” speech, in which he paid tribute to Irish heroes who had fought for Britain. “When I think of these days, I think also of other episodes and personalities. I do not forget Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde … and other Irish heroes that I could easily recite, and all bitterness by Britain for the Irish race dies in my heart. I can only pray that in years which I shall not see, the shame will be forgotten and the glories will endure, and that the peoples of the British Isles and of the British Commonwealth of Nations will walk together in mutual comprehension and forgiveness.”