By Frank Jastrzembki

Five busts of his greatest lieutenants during the Civil War watch over the sarcophagus of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at the General Grant National Memorial in New York City. The busts at Grant’s Tomb, the largest mausoleum in North America, are Generals William T. Sherman, George H. Thomas, James B. McPherson, Philip H. Sheridan, and Edward O.C. Ord. Of these five men, Ord is probably the least familiar to Americans.

Ord first caught Grant’s attention in 1862. Grant valued Ord’s aggressive fighting style, skillful management of troops, and promptness in battle. Grant was not the only one to notice his fine attributes as a commander. “I knew if there was a fight to be scared up, Ord would find it,” said Union Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds.

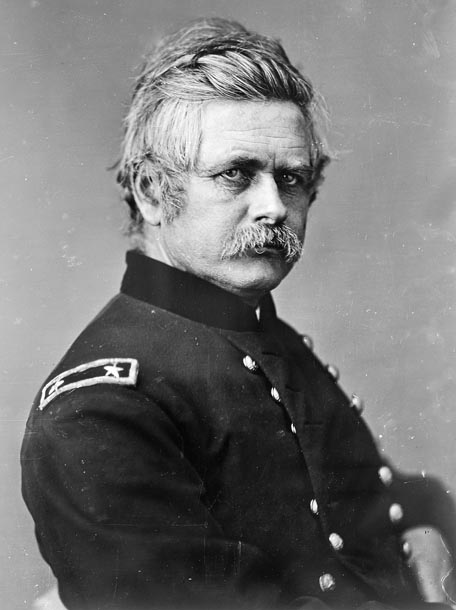

Edward Otho Cresap Ord was born at Cumberland, Maryland, on October 18, 1818. He was believed to have been an illegitimate grandson of King George IV. Ord “was brave and noble enough to have been a king himself,” wrote Julia Grant. Ord, who excelled at mathematics, received an appointment to West Point in 1835. During summer training, Ord shared a tent with Ohio native Sherman, and the two began what would become a lifelong friendship. Ord, who ranked 17th in a class of 31, received his commission as second lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment, U.S. Artillery upon graduation in July 1839. His first field service was in the Second Seminole War.

The ambitious young officer wanted an assignment on the front line when war erupted with Mexico in 1846. Although Ord never did see action during that conflict, he traveled with his friend Sherman in July 1846 by steamer from New York to California. While stationed in the Pacific Northwest, he saw combat against the Rogue River Indians in Oregon in 1856 and then against the Spokane Indians two years later in the Washington Territory.

It was not long afterward that the U.S. Army transferred Ord to Fortress Monroe, Virginia. When Colonel Robert E. Lee led his contingent of U.S. Marines to apprehend militant abolitionist John Brown at Harpers Ferry in October 1859, Ord was among the troops rushed to the U.S. arsenal at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Captain Ord was 43 years old. Unlike Brown, he had no abolitionist inclinations. Indeed, as a Marylander he had strong Southern ties and was a staunch Democrat. Like his former classmate, Virginian George H. Thomas, he stayed loyal to the Union despite his southern roots and sentiments. Through his influential friends in Washington, Ord was able to obtain an appointment as a brigadier general in September 1861. He received command of a brigade in Brig. Gen. George A. McCall’s division in the newly established Army of the Potomac alongside fellow brigadiers John F. Reynolds and George G. Meade.

Ord’s first action was in the clash with Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s mixed brigade of infantry and cavalry at Dranesville in Fairfax County, Virginia, on December 20, 1861. After a sharp contest, Stuart withdrew, leaving Ord in command of the field. Ord’s success at Dranesville was widely publicized in Northern newspapers, buoying spirits throughout the North in the wake of the twin disasters in northern Virginia at First Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff.

Thereafter, Ord commanded the 3rd Brigade in Brig. Gen. George A. McCall’s 2nd Division of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s corps that constituted the Department of the Rappahannock. These troops were charged with protecting Washington, D.C., while Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan launched his campaign against Richmond, Virginia, on the Virginia Peninsula. On May 3, 1862, Ord was promoted to major general.

Ord disliked McDowell and often quarreled with him. As Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s campaign in the Shenandoah Valley unfolded in the spring of 1862, McDowell’s corps was among the Union forces sent to contain the aggressive Confederate general. Ord, who by that time had received divisional command, was sent with Brig. Gen. James Shields’ division to Manassas Gap to check Jackson’s thrust north in late May that resulted in victories at Front Royal and Winchester. Ord did not perform with his usual pluck, possibly because of poor health. Indeed, Brig. Gen. James Ricketts took over command of his 9,000-man division as it approached Front Royal.

Shortly afterward Ord penned a letter to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton asking to be relieved and assigned to another command. Stanton granted his request, and in June Ord received orders to report to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck in Corinth, Mississippi. Ord took command of a division on June 2 in the District of West Tennessee under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Ord showed considerable initiative during the campaign, which consisted of the Battles of Iuka and Second Corinth in September and October, respectively.

Although Ord and Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans failed to coordinate their attacks in a pincer movement to crush Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s Army of the West at Iuka on September 19, Grant praised Ord for his promptness, while chastising Rosecrans for his excessive caution.

In an attempt to cut off Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn’s retreating Army of Tennessee following the Second Battle of Corinth, Ord’s detachment of the Army of West Tennessee captured Davis’s Bridge on the Hatchie River on October 5. Rather than simply hold the bridge, Ord pushed his troops across it, unaware that Van Dorn was in full retreat and he had stumbled into the vanguard, led by Price, of the retreating army. When he finally realized that his forces were in danger of annihilation, he headed to the front to rally them. As he was crossing the bridge, a Confederate canister round exploded, piercing his leg with an iron ball. Command devolved to Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut, who thought it wiser to leave the Yankee regiments in position than withdraw them under fire. The Confederates countermarched and found another escape route.

On the whole, Grant liked what he saw from the gutsy Marylander. The Iuka and Corinth campaign had marked the beginning of what would become a fruitful partnership that in some respects mirrored the one that Grant had with the irascible Sherman. Ord rejoined Grant in June 1863 after his leg wound healed. At the time, Grant’s Army of the Tennessee was besieging the strategic city of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. The commanding general had surrounded himself for the most part with a cast of able senior officers; however, XIII Corps commander Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand was an exception. The former Illinois congressman was disobedient, insubordinate, and incompetent. Simply put, he had no business commanding an army corps.

The very day that Ord arrived, Grant removed McClernand and put Ord in command of the XII Corps on the Union left flank. Ord immediately made improvements to the corps’ situation. He widened and connected the corps’ trenches, which made it easier to transfer artillery where it was needed most, and advanced them toward the enemy. These improvements tightened the corps’ grip on the Confederate works.

After the Confederate surrender on July 4, the XIII Corps transferred to the Department of the Gulf to serve under another political general, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks. Whereas his service at Vicksburg had been one of the high points of his Civil War career, his stint under Banks was one of the low points. Ord cringed at the thought of serving under Banks, whose incompetence was made clear by his performance during the 1862 Valley Campaign where he was derided as “Commissary Banks” for the amount of military supplies Jackson captured from his troops while he served in the Department of the Shenandoah. Ord contracted a severe respiratory infection and after three months under Banks submitted a request in October to be allowed time to recover.

Unfortunately, after Ord returned to command in January 1864, Lincoln reinstated McClernand to command of the XIII Corps the following month. At that point, Ord found himself transferred to the Department of West Virginia to serve under yet another political general, Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel. Ord avoided serving under Sigel by requesting to be relieved of command. After the request was granted, Ord pondered his next move. He strongly desired to serve under a competent commanding general in an active theater.

It would not be long before Grant called on him again during an emergency. On March 1, 1864, President Lincoln had appointed Grant lieutenant general and commander of all Union armies. From his headquarters at City Point on the James River, Grant wrote on July 10, 1864, to Halleck informing him that he “would give more for him [Ord] as a commander in the field than most of the generals now in Maryland.”

The Union high command was furious with Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace for suffering a defeat at the hands of Lt. Gen. Jubal Early at Monocacy Junction on July 9, and the following day Chief of Staff Halleck sacked Wallace. General Order No. 228, issued two days after the Union defeat at Monocacy, gave Ord command of the VIII Corps and all of the troops in the Middle Department. Grant ordered Ord to “press into service every able-bodied man to defend [Baltimore].” Ord acted with speed, energy, and resolution. Although his troops in and around Baltimore braced for an assault, it fell on Washington instead where Early probed the defenses of the Union capital at Fort Stevens on July 11-12. The following day, Old Jubilee crossed back into Virginia via White’s Ferry.

Once the crisis was over and Early had departed Maryland, Grant ordered Ord to report to his headquarters at City Point in southeastern Virginia. Grant subsequently appointed Ord to succeed Maj. Gen. William Smith as commander of the XVIII Corps, which was part of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James. Butler’s army anchored the right flank of the Union line stretching from Petersburg to the Appomattox River.

Following the disastrous Battle of the Crater in July 1864, Grant ordered most of the Army of the James to cross the James River and threaten the Confederate capital of Richmond. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, led 25,000 men on a march that took them south of Petersburg. To keep the crossing of the James River at Aiken’s Landing at a pontoon bridge by his 8,000 men a secret, Ord chose to issue verbal orders in lieu of written ones to ensure that they did not fall into enemy hands.

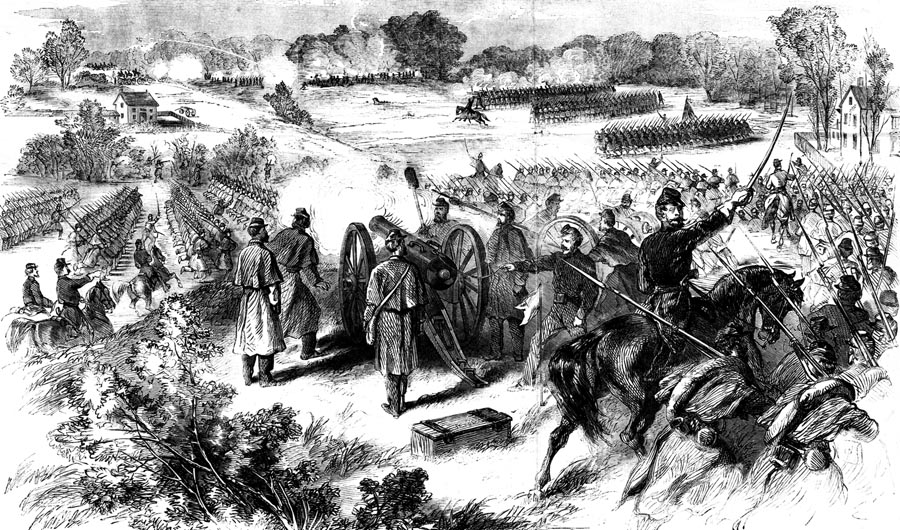

Ord, on Butler’s left wing, led two of his divisions along Varina Road toward Fort Harrison, the strongest of the forts protecting Richmond. Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard’s First Division of the XVIII Corps spearheaded the assault on September 29 in what became known as the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. The Yankees had to advance across 1,400 yards of open ground into the teeth of Confederate guns on the fort’s ramparts. The artillery fire was so severe that it mowed lanes through the mass of bluecoats as they charged. When they reached the fort’s moats, Stannard’s men hurled themselves across the obstacle to engage the Rebels in fierce hand-to-hand fighting.

The fighting was vicious and chaotic. Of Stannard’s three brigade commanders, one was slain and the other two severely wounded. The blow to the command structure left the Union troops milling around inside the fort unsure of their next move. Ord’s command suffered 30 percent casualties in order to capture Fort Harrison.

Realizing the danger to his entire line, General Lee rushed reinforcements to support the outnumbered defenders. Ord had to think quickly. In an effort to regain control of his disorganized troops, he directed a party of company officers and skirmishers to capture and destroy the Confederate pontoon bridges to prevent the Confederate reinforcements racing to the point of crisis from arriving. Ord sensed that the Confederate capital, for four long years an objective that the Union never could capture, was ripe for the taking.

But the gods of war did not favor Ord capturing Richmond on that day. A Confederate ball sliced through his leg. He bound his bloodied leg with a tourniquet and continued to issue orders from an ambulance wagon until a surgeon urged him to leave the field to be treated. He rode off in the wagon to try to find Grant and plead for reinforcements. But it was too late. Ord’s inexperienced replacement became overwhelmed in his new role and failed to follow up the initial success. If Ord had not been wounded, Union forces might have been able to capture Richmond’s outer defensive ring and threaten the Confederate capital.

In December 1864, Butler consolidated the VIII Corps and X Corps to form the new XXIV Corps and placed Ord in command. Grant subsequently removed Butler from command of the Army of the James in January 1865 and replaced him with Ord. The move made the native Marylander the third most important man on the Richmond-Petersburg front with 50,000 men under his command. As such, only Grant and Meade outranked him.

Grant ordered Ord to pull three divisions from his line and support the Army of the Potomac’s thrust against Petersburg at the end of March 1865. When the Union army shattered the Confederate position at Petersburg on April 2, Lee led his army west toward Lynchburg all the while hugging the Southside Railroad.

Ord not only had charge of his own army during the final pursuit south of the Appomattox River, but also was entrusted by Grant with the V Corps. His orders were to cooperate with Sheridan’s cavalry corps. At one point, Ord’s men marched for 26 hours with no more than a total of three hours rest.

Meanwhile, Grant and Meade marched with the main body of the Army of the Potomac to cut off Lee’s line of retreat. If Lee managed to escape the Grant-Ord-Sheridan pincer movement, he would be able to unite with General Joseph E. Johnston’s army battling Sherman in North Carolina. Ord, wearing an old battered felt hat and a muddy oilcloth coat, exhorted his men to march just a little while longer. He knew they were exhausted, but he also knew the end was in sight.

When Ord learned that Lee had finally agreed to surrender, he was ecstatic. He rode down the column shouting, “Your legs have done it, my men,” recalled Brig. Gen. Joshua Chamberlain. Thus, Ord gave his men the credit they deserved for their role in the Appomattox campaign.

If anyone wanted to see the war come to an end, it was Ord. He was fortunate to be one of the Union officers present with Grant at the McLean House when Lee signed the surrender. Afterward, Ord purchased the marble-top table where Lee signed the surrender document.

Ord remained in the army after the war, commanding several departments during Reconstruction, one of which was the Department of Texas. After accepting the post in 1875, Ord helped keep the peace on the U.S.-Mexican border. This occasionally involved pursuing renegade Indians and bandits into Mexico. During this time, he worked closely with his counterpart on the Mexican side, Jeronimo Trevino. In 1882 Trevino wed Ord’s daughter Roberta. At times at odds with his superiors on his policy, Ord worked hard to keep the border safe and maintain good relations between the neighboring countries.

Nineteenth U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes signed the order forcing Ord into retirement at the mandatory age of 62 in December 1880. He was reluctant to turn over command after 45 years of service in the army. Broke and unemployed, Ord subsequently worked as a civilian agent in Mexico for the Southern Pacific Railroad and Standard Oil Company. After his term of employment ended, Ord joined another company, the Mexican Southern Railroad, which was managed by Grant. While working under Grant, Ord laid the groundwork for a railroad connecting Mexico City to Oaxaca.

While returning from Mexico by steamer to New York, Ord contracted yellow fever. He succumbed to the disease on July 22, 1883, in Havana, Cuba. His body initially was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C., but it was relocated to Arlington National Cemetery in 1900.

Throughout his career, Ord proved himself to be a resourceful, brave, and aggressive commander. Although Ord was occasionally willful and cantankerous, Grant overlooked these flaws and brought the best out in him. Grant’s faith in Ord is evidenced by the way he gave Ord important posts during some of the Union Army’s greatest campaigns, most notably, Vicksburg, Petersburg, and Appomattox.