By David A. Norris

Wind lifted away the fog sheltering the French lines. Atop a low ridge where the French army was deployed, a lone windmill provided a vivid range marker for 58 Prussian cannons on the neighboring hills. Shot fell like black hailstones amid the staff officers by the man-made landmark. French commander General François Christophe de Kellermann narrowly escaped death from a cannonball that tore through his saddle cloth and killed his horse under him. There was a flash of fire when a Prussian shot exploded a French ammunition cart. Two battalions of infantry bolted from their posts, and panicky artillery drivers fled with their wagons. To Prussian observers on September 20, 1792, it looked as if the Battle of Valmy was going to be the beginning of the end of the French Revolution.

When the uprising against King Louis XVI began in 1789, intellectuals guided the revolutionary movement under the rational ideals of the Enlightenment. But they lost control to the chaotic and violent voices of the Jacobin faction, which demanded immediate and radical reforms. At the top of their list was bringing an end to the privileges and high status of the nobility and the abolition of the monarchy.

The French royal family, fearing the worst, decided to flee the country. On the way to the citadel of Montmedy at the border with Flanders, the king’s carriage stopped at the little town of Sainte-Menehould on June 21, 1791. The postmaster recognized the king from a royal portrait on an assignat (a piece of paper currency). Alerted by the postmaster, antiroyalists arrested Louis XVI at Varennes and sent him back to Paris.

Queen Marie Antoinette of France was the sister of Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor and the ruler of Austria. Concerned for the safety of Louis XVI and the royal family, Leopold II, together with King Frederick William II of Prussia, issued the Pillnitz Declaration on August 27, 1791. The document threatened retaliation if the French royals were harmed.

The revolutionaries in Paris considered the document an affront. Already the radical leaders worried about the intentions of the growing forces of royalist exiles in the Austrian Netherlands. On April 20, 1792, France declared war on Austria. Prussia, Great Britain, and smaller monarchies joined Prussia to form an antirevolutionary alliance. Thus began the War of the First Coalition.

France was in poor shape for war. Her army had deteriorated in size and quality during the reigns of Bourbon kings Louis XV and Louis XVI. Aristocrats faced the growing prospect of imprisonment, and many fled the country.

Politics spilled into the French army. Military officers were from the upper reaches of society, and many of them resigned or were purged from the army, costing France many skilled and experienced leaders. Soldiers no longer feared their aristocratic officers, and many men suspected or accused their superiors of treasonous loyalties. France had a long tradition of hiring Swiss, Germans, and other nationalities and enrolling them in special regiments. Tainted with suspicion of royalist leanings, many of these troops were exiled. They promptly became trained recruits for the armies of revolutionary France’s enemies.

With the outbreak of the new war, France planned an invasion of the Austrian Netherlands. Three forces, the armies of the North, Center, and Rhine, had already been formed to protect the boundary regions of northeastern France.

The opening of the Flemish campaign was a disaster. On April 29, Marechal de Camp (brigadier general) Count Theobald Dillon led a small force from Lille toward Tournai. His advance was merely a diversionary attack to cover the main attack on Mons, and he was ordered to avoid battle. Dillon, the son of an Irish viscount, was resented by his sullen and insubordinate troops.

Halfway between Lille and Tournai, near a village called Baisieux, a larger Austrian force confronted Dillon. When the Austrian artillery opened fire, the Irish officer fulfilled his instructions and ordered a retreat. His infantry filed away as commanded, but anger surged through the cavalry. Horsemen suspecting treachery shouted, “Save yourselves! We are betrayed!” Orderly withdrawal turned into a panic. Dillon was wounded while trying in vain to rally his men. Placed in a cabriolet, the stricken commander followed the retreating army.

Believing they had been sold out, the soldiers turned on and killed several of their officers. When Dillon reached Lille, mutinous soldiers attacked him with bayonets. Stabbed countless times, the body of the dead general was dragged through the streets and tossed on a bonfire. Although the soldiers accused of his murder were executed, the incident left the officers and rank and file in mutual suspicion of each other.

The Flemish invasion collapsed. Turmoil still gripped France. On August 10, 1792, mobs attacked the Palais des Tuileries, the royals’ Paris residence. Six hundred Swiss guards were killed defending the king. Louis XVI and his family were placed under arrest. Early in September, Paris mobs broke into the city’s prisons, slaughtering hundreds of political prisoners and ordinary criminals.

At the end of July, the coalition had assembled more than 150,000 troops in three armies. The main army, numbering about 84,000, marched into France on August 19. Of this army, Prussia contributed 42,000 troops, and the Austrians provided 29,000. Also with them were about 5,000 Hessians and 8,000 French émigrés.

Officially, the main coalition army was under the command of Charles William Ferdinand, the Duke of Brunswick. The duke was the husband of Princess Augusta, sister of King George III of Great Britain. A popular and respected ruler, he had also proved himself a capable general in the Seven Years’ War and subsequent smaller conflicts. Flemish-born General François Sebastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt, commanded the Austrians.

Supreme command of the Prussian and Austrian forces, however, went to the monarch of Prussia, King Frederick William II. Ruler of Prussia since 1786, the king succeeded his uncle, Frederick the Great. The new king preferred intellectual and artistic pursuits over military matters. But he accompanied the main army when it invaded France and asserted his authority when his ideas clashed with those of the Duke of Brunswick.

Paris recalled the commander of the Army of the North, Gilbert de Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette. Fearing execution at the hands of the radicals, this veteran of the American Revolution fled the country. Appointed as the new head of the army was General Charles-François du Perier Dumouriez. A high-ranking veteran officer, he had turned to the revolution more to advance himself than for political idealism.

Dumouriez’ counterpart, in command of the Army of the Center, was a Strasbourg-born veteran of the old royal army, Kellermann. Despite achieving the high rank of marechal de camp during his years of military service, Kellerman was attracted to revolutionary ideals.

After entering France on August 19, the coalition leaders disagreed on strategy. Brunswick worried that the army would find itself deep in France with autumn and winter looming. Supplies from the countryside were scarce, and the population was hostile and offered little voluntary help. Brunswick preferred, once some of the fortresses of northeastern France were taken, to wait out the winter and begin a new campaign in the spring of 1793.

King Frederick William overrode the duke’s cautious strategies. The king fully believed the French émigrés when they vowed that masses of Frenchmen loyal to the Bourbon dynasty would join the Germans. Together, they would scatter the amateurish revolutionary army, whose officers the émigré leaders dismissed as “barbers” and “tailors” rather than soldiers.

German writer and thinker Johann Wolfgang von Goethe accompanied the army. He was invited as a civilian guest of Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, who commanded a regiment of Prussian cuirassiers. In a September 2, 1792, letter to his mistress, Christiane Vulpius, Goethe reflected the army’s confidence when he promised he would soon be shopping for her in Paris.

But reality was already setting in and would soon tarnish the spirits of the army. Rain fell with such persistence that the Germans joked that Jupiter (Roman god of the skies) was a Jacobin.

On September 2, the fortress city of Verdun fell to the coalition army. Next, the Prussian king intended to march to Chalons and from there to Paris. Chalons was beyond the western edge of the Forest of Argonne, later to be the site of Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918.

For an 18th-century army, the Forest of Argonne was a formidable barrier. A miniature mountain range, the forest’s thickly wooded and broken terrain ran about 40 miles from north to south. Ravines, gullies, and streams lined with marshes slashed through the forest. An army burdened with wagons, carts, and guns could pass through the Argonne only by way of a few roads following natural passes.

Lieutenant General Arthur Dillon (the unfortunate Theobald Dillon’s cousin) held on to the central pass at Les Islettes through which ran the main road from Verdun to Chalons. Dumouriez held the pass at Grand Pre, which lay to Dillon’s north. Rather than force these heavily defended passages, the Prussians were willing to invest several days in marching to the northerly pass of Crois-au-Bois, where Clerfayt’s Austrians brushed aside a thin screen of 100 French soldiers.

During the withdrawal, a force of Prussian hussars routed part of Dumouriez’ army. Several thousand troops fled for 30 miles or more, spreading wild rumors as far as Chalons and Reims that the army was destroyed, and the enemy was marching freely toward Paris. “We are betrayed! All is lost!” the panicked volunteers cried. Fortunately for the French, clear-headed officers organized a defense and repulsed the hussars.

The coalition army passed through the Argonne and marched west and south into the plains of Champagne. If they expected the French to withdraw to the west and hold Chalons, they were proved wrong. Outflanked, on September 15 Dumouriez withdrew south to the town of Sainte-Menehould, about four miles west of Les Islettes. The little town of Sainte-Menehould had another brush with European history as Dumouriez camped there and waited for Kellerman to join him from Metz. At that point, the French had a good defensive position along the road to Chalons and Paris, but it lay in the rear of the coalition army.

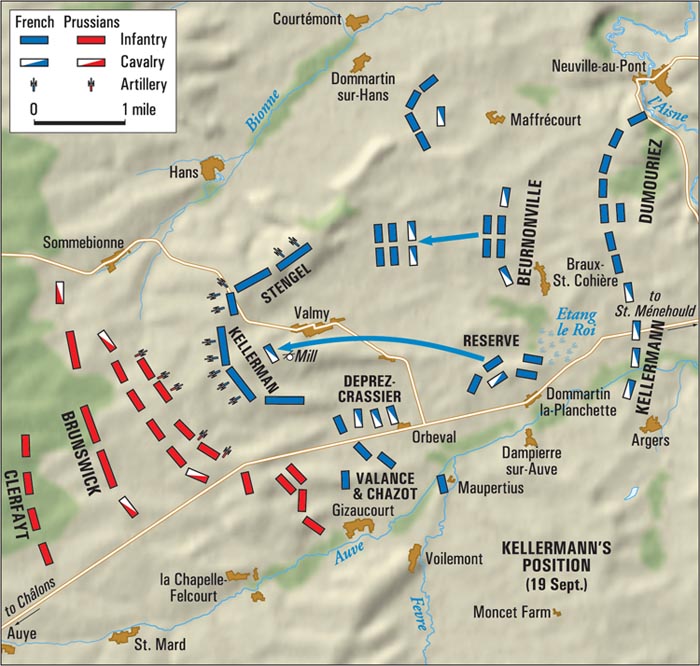

Kellermann’s arrival with the Army of the Center gave the French a combined force of 36,000 men, but the army was under divided leadership. Although Dumouriez had the largest force, he could only offer advice and observations because Kellermann was not under his command.

The Army of the Center camped along the Chalons Road at the village of Dommartin-la-Planchette on September 19. This was, Kellermann realized, a dangerous spot. Between his camp and Dumouriez’ troops was a large pond. Behind him was the Auve River, which was lined with wetlands. Two miles away was the village of Valmy atop a hill offering any advancing foe a perfect setting for his artillery to bombard the French camp.

Kellermann decided to shift his force to Valmy. As an advance guard, he sent Lt. Gen. Étienne Despres-Crassier to the west, where he halted on a hill.

The coalition army made slow progress after crossing the Argonne. Rather than marching for Chalons, King Frederick William II worried about the French army behind him at Sainte-Menehould. The army turned to deal with Dumouriez and Kellermann.

On the night of September 19, the Prussians were in the advance and camped at Somme-Tourbe, half a dozen miles from Dommartin-la-Planchette. Goethe wrote that the king settled in a hotel, while the Duke of Brunswick occupied “a kind of shed” by the hotel.

September 20 began as a chilly morning of fog and rain. Only 34,000 coalition troops, nearly all Prussian, were on hand as Frederick William II and the Duke of Brunswick pushed them ahead toward the French. Thousands more of the Prussians were tied up holding captured fortresses or watching the Argonne. Clerfayt’s Austrians and the French émigrés were miles to the northwest. They were delayed by their march from Grand Pre and slowed further by reports of nonexistent French forces in their way.

After daylight, Kellermann’s army reached the hill of Valmy. Without the fog, it would have been easy to see the site’s defensive advantages. Topped by a lone windmill, the hill with its gentle slopes was the highest point in a great panorama of rolling farm country. Few trees or woods interrupted the vista of open fields and pastures. To the north was a low ridge called Mont Hyron, which looked down on and paralleled the little Bionne River. To the south was the Chalons Road, beyond which was the hamlet of Gizaucourt near the Auve River. To the west, the road from Somme-Tourbe joined the Chalons Road. At the road junction was another rise, not so high as that of Valmy, marked by an inn called the Cabaret de la Lune. The inn was about 11/2 miles from the Valmy windmill.

Blindly plodding through the fog, three squadrons of Prussian hussars came under fire. They had stumbled into a small number of French troops who occupied la Lune. These were the first shots of the Battle of Valmy.

The main portion of the Prussian force was just reaching a farm called Maigneux, not far from the Chalons Road. Major Christian Karl August Ludwig von Massenbach, a Prussian staff officer, rode ahead with the Duke of Brunswick’s son, Count Forstenbourg. After covering 1,000 yards, they found themselves at la Lune. The Prussian hussars had driven the French away from the inn, which was now pocked with bullet holes. The yard was littered with shattered roof tiles and dead or wounded French soldiers. One artillery officer lay among them, with both of his legs broken. Massenbach ordered the Frenchman carried inside the inn.

Forstenbourg and Massenbach both saw that their army must hold the elevated ground at the battered inn. Whichever side held la Lune could cover the Chalons Road and the surrounding countryside. The two staffers rode back toward the main army, hoping to convince their superiors to commit enough troops to occupy the hill. Both officers lost precious minutes feeling their way through the fog. Finally, they informed the Duke of Brunswick of la Lune’s importance. The duke dispatched two staff officers to la Lune, one with a battery and the other with a battalion of grenadiers. Massenbach himself took another battery and headed to the front.

At the same time, Dumouriez learned that la Lune was given up and ordered General Jean-Pierre François de Chazot to retake it. Before obeying the order, Chazot stopped to ask Kellermann’s opinion. Kellermann, it turned out, agreed with Dumouriez that the hill was a vital position that should be held. Chazot then complied with his orders and started for la Lune.

When Massenbach and his battery rolled toward la Lune, they saw Chazot approaching in the distance. The Prussian drivers cracked their horsewhips, and they dashed the final yards up the slope and set up their guns. Behind them pounded the drummers of the grenadier battalion, their drum rolls blending into the noise of the first loads of grapeshot fired at Chazot. The heights of la Lune hung in the balance for a few moments. From the right, crossing the Auve, Colonel Erich Magnus von Wolffradt arrived with 10 squadrons of hussars. Chazot withdrew, leaving la Lune as the anchor of the Prussian line in the coming battle.

Marching southeast from their camps at Somme-Tourbe and Somme-Suippes came the main portion of the coalition army in two columns. One column was under Brunswick and Frederick William, and the other under Lt. Gen. Frederick Adolf, Count von Kalkreuth. Still moving in the fog, the Prussians formed a line with their right spilling beyond la Lune, and their left on the Bionne River.

Goethe, intent on observing the battle in the way a scientist might study natural phenomena, rode with a cavalry squadron on the Prussian right. It seemed safe enough. They thought they were heading toward one of their own batteries, and they believed that the French lines were too distant to concern them. They were surprised when a French battery, sited forward of the main line, fired at them out of the fog. “Balls were falling by dozens … not rebounding, luckily, for they sank into the soft ground; but mud and dirt bespattered man and horse,” wrote Goethe. The shriek of soaring shells fascinated the observer. “The sound of them is curious enough, as if it were composed of the humming of tops, the gurgling of water, and the whistling of birds.”

Dumouriez remained at his camp, but he believed that Kellermann had selected a poor place to stand against the Prussians. The hill of Valmy was too exposed to enemy guns. The French were crowded too tightly together, and the flanks were vulnerable. For those reasons, Dumouriez sent Bavarian-born veteran General Henri Christian Michel de Stengel to reinforce Kellermann’s right. Stengel deployed his troops along Mont Hyron, and Chazot was ordered to shield the French left.

Late in the morning, the winds stirred and blew away the fog. Sweeping in a great convex arc, Kellermann’s line came into focus 1,300 yards in front of the Prussians. Bristling from the French line were 40 guns under Lt. Gen. Francois-Marie d’Aboville. The sexagenarian had served as a teenager at Fontenoy in 1745 and later commanded Count Rochambeau’s artillery at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. Prussian Colonel George Friedrich von Tempelhoff commanded 58 guns, which bolstered the Prussian infantry. Tempelhoff fired a blistering barrage at the lines around the Valmy windmill. Kellermann’s horse was shot from under him. The French commander escaped serious harm, but several staff officers near him were struck dead or seriously wounded.

Kellermann’s mistake in crowding too many troops together on the ridge triggered a crisis. With considerable carelessness, carts loaded with gunpowder were parked close to the formations of foot soldiers near the windmill. An enemy shell struck an ammunition cart at approximately 2 pm. The resulting explosion touched off two nearby cartloads of powder. “I saw whole ranks swept away by the explosion … without the line being broken,” Kellerman wrote in his report, brushing off the incident.

The situation around the windmill was more serious than Kellermann acknowledged. The fire and smoke of the explosion were visible from the coalition lines. Goethe and his companions “rejoiced in the mischief which was thus probably caused to the enemy.” And for some minutes, there was considerable mischief. Fragments of shattered carts and mangled horses rained down among the soldiers. Two battalions of infantry bolted from their position near the site of the blast, leaving behind many dead or wounded comrades.

The artillery drivers were not soldiers, but farmers forced into emergency service by the Jacobin regime. Lashing their horses, the panicked farmers sped away with their still loaded carts. With most of their ammunition gone, the batteries on the Valmy hill slowed their fire.

Steady officers prevented the surprise explosion from unraveling the line. D’Aboville quickly brought more ammunition to the ridge, and the French artillery resumed its fire.

The young Louis Philippe d’Orleans, Duke of Chartres, calm and highly visible on his horse amid the turmoil, lent his aid to the line officers as they steadied and reformed their battalions. Only 19 years old, the duke’s high rank as a division commander was due to his status as the son of the Duke of Orleans, one of France’s wealthiest men and the head of the cadet branch of the royal family. “I have never seen a general as young as you,” Dumouriez said upon their first meeting. “I am the son of the man who made you a colonel, and I am entirely at your service,” the duke replied.

Brunswick and his staff saw the temporary chaos in the French lines. It looked like a good moment to launch an attack, and the duke sent his infantry forward. They moved slowly across the hundreds of yards between their lines and hesitated under the heavy artillery bombardment.

As the enemy troops marched closer, Kellermann raised himself in his stirrups. He was fortunate that a great portion of his army, especially the artillery, was made of professional troops of the old royal army. Just the same, the Jacobin-inspired volunteers under his command could hardly inspire the confidence of a commander. Prussian hussars had ignited a stampede of his troops only a few days ago, and the murder of Count Theobald Dillon at the hands of his mutinous troops five months before was an ominous precedent.

Kellermann, though, showed no sign of concern about how the men would face this crisis on the hill of Valmy. He removed his hat, placed it on the tip of his saber, and raised his sword arm high in the air, shouting, “Vive la Nation!” Electrified by the general’s example, the soldiers answered, “Vive la Nation! Vive la France! Vive Notre General!”

Amid the cheers, army musicians struck up the new tunes that were inspiring the revolutionary movement: “Ca ira,” “La Carmagnole,” and “La Marseillaise.” So popular was the second song that the ragtag new soldiers recruited from among the peasant and working class radicals were called “carmagnoles.” “La Marseillaise” remains the national anthem of France. “The Cry of Valmy” became a legendary moment in French history. The soldiers would fight not for the king, but for their nation.

Some of Kellermann’s volunteers had already pleasantly surprised their commanders. One of the Duke of Chartres’ battalions was made up of new recruits. Its men refused orders to remain in the rear and guard the baggage trains. Confronted by the duke, a spokesman said, “General, we are here to defend our country, and we entreat you not to require any of us to leave the standard of our battalion for the purpose of guarding the baggage.”

“Very well,” answered the duke, “your baggage must take care of itself for today, and your battalion shall march along with your fellow soldiers of the line.”

French foot soldiers pressed ahead to trade volleys with the enemy. One of the new volunteers was a 15-year-old former clerk named Charles François, who was assigned to the 5th Paris Battalion. A bullet hit young François. The ball whizzed by over his right ear and “only just grazed the skin and went clean through my hat,” he wrote years later. “I was very proud of that hat, and kept it for a long time.”

Neither side pushed their infantry too far. In the face of the advancing French and the incoming artillery fire, Brunswick recalled the Prussian battalions, and they returned to their lines.

After the infantry returned, the artillery fire rolled on. At 4 pm, the Prussian foot formed for another advance against the hill of Valmy. Like the first assault, though, this advance made little headway before the troops were recalled.

The rescinding of the second order for an infantry advance marked the end of any offensive moves by the Prussian infantry that day. Brunswick called a quick council of war. “We do not fight here,” the duke told his staff. King Frederick William did not object.

Later the duke told Massenbach that the situation bore an unsettling resemblance to the 1762 Battle of Nauheim during the Seven Years’ War. At Nauheim, the French troops occupied a height much like the ridge Kellerman held at Valmy. Brunswick, under the impression that he faced only a portion of the enemy, launched an attack against the ridge. Unknown to him, the entire French force was on hand, and the duke’s error brought a painful defeat upon his troops. Three decades later, Brunswick wanted no repeat of Nauheim.

After the recall of the Prussian advance, the roar of the artillery slackened as it became clear that there would be no more attacks coming that day. By the time the firing ceased at 6 pm, approximately 20,000 rounds of artillery ammunition had been expended that day.

French casualties were approximately 200 killed and between 500 and 600 wounded. The Prussian losses were one artillery officer and 44 men killed, and four officers and 134 men wounded for a total of 183 casualties, according to one detailed Prussian account. Kellermann’s deployment of so many troops in a small space on the exposed heights of Valmy contributed to the higher French toll. Goethe’s observation of cannon balls plunking into the wet clay soil without ricocheting and rolling partly explains why such a heavy cannonade resulted in rather low losses for a major engagement.

“The cannonade had scarcely ceased when wind and rain again commenced, and made our condition most uncomfortable on the spongy clay soil,” wrote Goethe. There were only four guest rooms at the battered Cabaret de la Lune. The King of Prussia and the Duke of Brunswick each took one room. Three princes packed into another room with some of the king’s aides. The fourth was packed with wounded soldiers, including the fellow Massenbach had looked after that morning. Staff officers slept in the dining hall.

The rest of the Prussians did as best they could outdoors where they were exposed to the elements. Massenbach slept on a bale of hay, his reins tied to his ankle. Goethe and his companions had no shelter. Their solution was to “bury ourselves in the earth and cover ourselves with our cloaks.” Even “the Duke of Weimar did not despise this kind of premature burial,” Goethe wrote.

Although their battle was successful, Kellermann and Dumouriez agreed that their position was dangerous. Leaving their campfires flaring, as if settled in for the night, the army instead slipped away. The next day found the French in a better situated line south of the Auve.

French troops still blocked Grand Pre. They intercepted cattle droves and supply wagons bound for the coalition army. Meanwhile, the peasantry resisted helping the invaders. Prussian deserters informed the French that they had been reduced to eating horses killed during the cannonade.

Far deadlier than French guns were the invisible pathogens that spread dysentery through the coalition forces. The deadly outbreak of what the French called la couree Prussienne was serious enough to earn a place in 19th-century medical literature. The role of microbes in causing disease was of course unknown, and this epidemic during the Valmy campaign was often attributed to soldiers eating unripe grapes and potatoes. In vain, army surgeons treated patients by bleeding them or dosing them with rhubarb, ipecac, or even lemonade. Approximately 12,000 of the 42,000-man army came down with dysentery, and a great portion of them died.

For 10 days, the Duke of Brunswick hovered at La Lune while dysentery and food shortages ate away at his army. After 10 days, on September 30, he broke camp and led the army toward home. Dumouriez let them slip through the Argonne. In early October, the Prussians gave up Verdun. Dysentery and the long, insecure supply lines finally induced the coalition army to leave France altogether.

After Valmy, Dumouriez grew disenchanted with the regime. In March 1793, he plotted with the Austrians to lead his army to Paris and restore the monarchy. When his plans were discovered, he fled. Drifting about Europe looking for employment, he eventually came into the pay of the British as an adviser. He died in England in 1823.

Even the hero of Valmy was not above suspicion and denunciation, and Kellermann was imprisoned for over a year when he fell afoul of the radicals in Paris. Upon his release, he went on to a long career in military administration and in French politics. While in Napoleon’s service, he was made a duke in 1808. Marking his victory of 1792, Kellerman took the title of Duke of Valmy. After the fall of the First Empire, he remained in the government of the restored Bourbon monarchy. Following his wishes, upon his death in 1820 the duke’s heart was buried on the Valmy battlefield.

As for the Duke of Chartres, he went into exile after getting entangled in plotting by Dumouriez. He settled in England after traveling as far as Cuba and the United States. Returning home after the fall of Napoleon, he was crowned King Louis-Philippe of France in 1830.

Approximately 70,000 soldiers were present at the Battle of Valmy, but the casualty lists resembled those of a large skirmish. Indeed, many historians referred to the action not as a battle, but as “the Cannonade of Valmy.” Yet the results of the battle echoed through European history. As the first victory of the revolutionary regime over foreign enemies, Valmy proved that the so-called citizen army of France could defeat armies fielded by traditional monarchies of Europe.

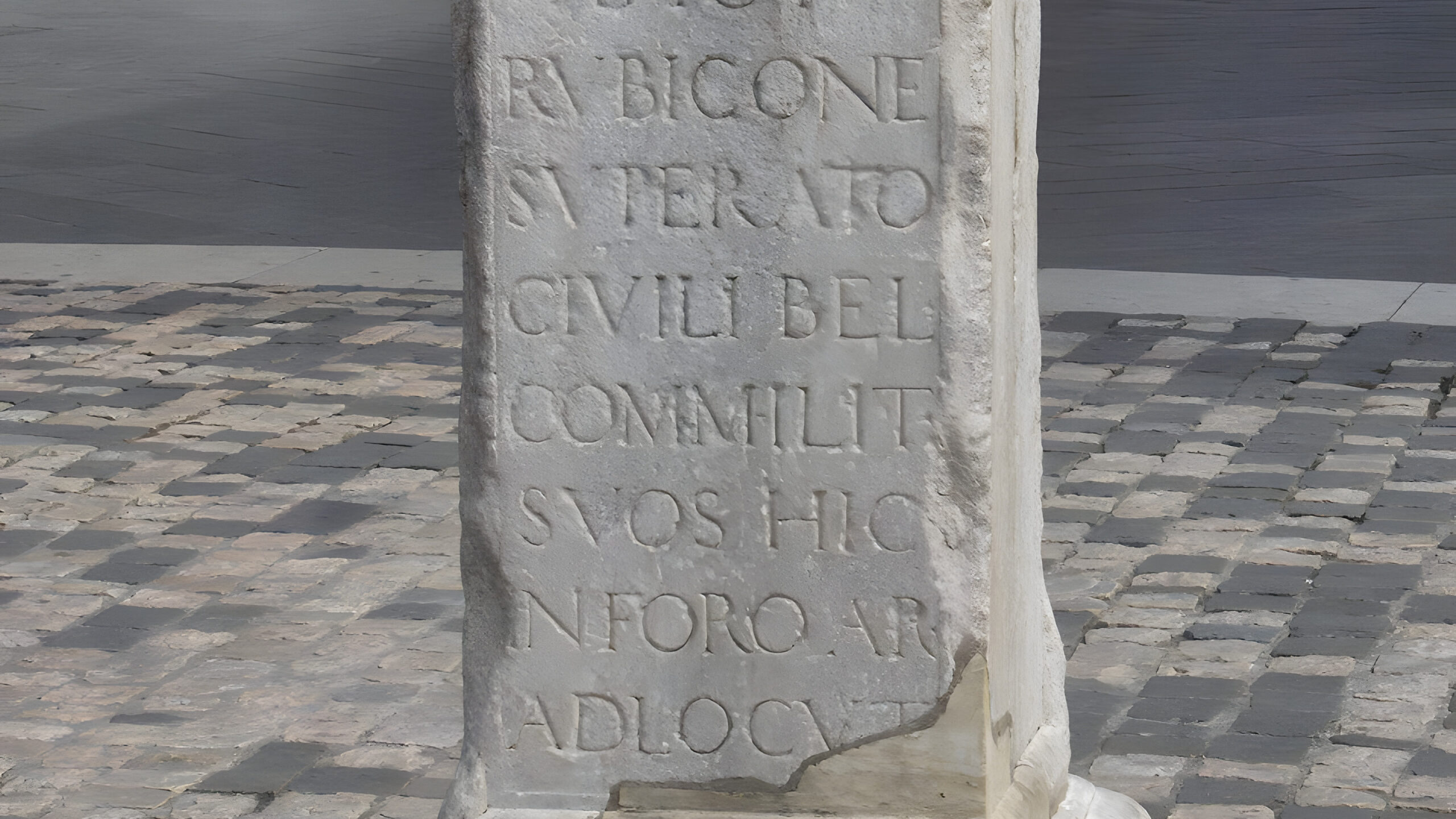

Goethe realized that the outcome of the September 20 “cannonade” would forever alter European politics. Sharing a campfire with some officers on the night of the battle, Goethe assured them, “From today and from this place begins a new epoch in the history of the world and you can all say you were present at its birth.” Indeed, buoyed by news of the victory, the National Convention declared that the monarchy was at an end. On September 22, 1792, France became a republic.

Building on the gains of Valmy, French forces pushed into the Rhineland. Dumouriez resumed his invasion of the Austrian Netherlands in October and took Brussels and Antwerp. An army once seething with chaos and mutiny was poised to spread the doctrine of revolution across all Europe.

Although the radical fervor of the Jacobins soon burned itself out in the so-called Reign of Terror, Napoleon Bonaparte, a rising star in the French Revolutionary Army, harnessed the political forces set in motion by the French Revolution to further his own ambitions. France, in less than a decade, would transition from monarchy to republic to empire under Napoleon. Valmy set the stage for more than two decades of violent upheavals that would convulse Europe and much of the world until 1815.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments